19th Century

19th Century

Rival Medical Schools

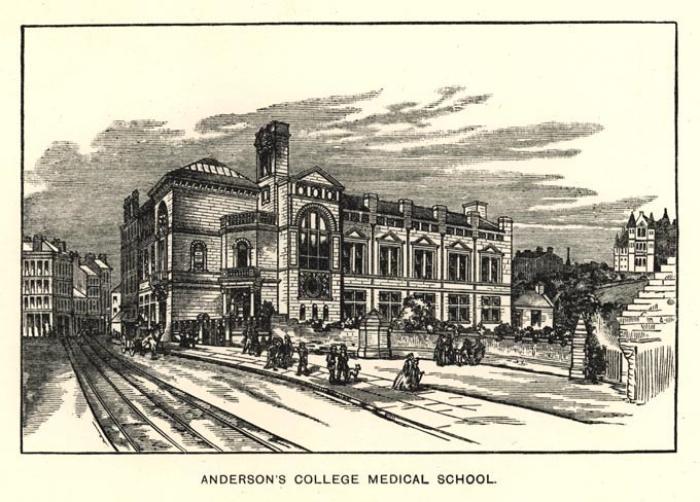

At the end of the 18th Century, in 1797 John Burns set up his own private medical school in College Street, close to the University of Glasgow. It continued to offer instruction until the mid 1830s. Though it had no formal links with the University, students often attended courses at both. Burns taught anatomy, surgery and midwifery at his school and later lectured in these subjects at Anderson's College. Anderson's College had opened in 1796, to rival the University of Glasgow at the bequest of a former Professor of Natural Philosophy, Dr John Anderson.

Later it was to become the University of Strathclyde in 1969. Burns was ultimately appointed first Professor of Surgery at the University in 1815.48 Many able men were connected with these schools and subsequently occupied Chairs in the University.49

Surgical teaching begins at the Royal

Despite the early start made by Cleghorn and Hope in 1794 and Burns in 1797, the provision of clinical teaching was still irregular. In 1810 a letter from the 'medical students of the town' was addressed to the managers asking that a course in clinical surgery be given at the Infirmary to supplement the medical clinical instructionprovided at the hospital.

Despite the early start made by Cleghorn and Hope in 1794 and Burns in 1797, the provision of clinical teaching was still irregular. In 1810 a letter from the 'medical students of the town' was addressed to the managers asking that a course in clinical surgery be given at the Infirmary to supplement the medical clinical instructionprovided at the hospital.

Although in Edinburgh and London, clinical surgery courses had not been as well attended as clinical medical courses it was recommended that existing surgeons appointed at the Infirmary shouldbe encouraged to give lectures on any cases considered appropriate.50

A curriculum is established

Between 1787 and 1802, 117 medical degrees were conferred. Thirty of these students had studied at the University of Glasgow. Many graduates were of Irish or American descent. The candidates were examined by two medical professors and if approved were set a medical case and an aphorism of Hippocrates51 (a long series of propositions concerning the symptoms and diagnosis of disease and the art of healing and medicine).52 The solution of the former and the discussion of the latter (in Latin) were submitted to a meeting of the Senate and this was followed by a Latin thesis, which had to be defended before the whole university.

In 1801, the University Senate appointed a committee to inquire into the existing regulations for medical degrees and the first definite curriculum was established in 1802. This required three years of medical study and evidence of attendance at courses in anatomy, surgery, chemistry, the theory and practice of medicine and botany. There were three examinations: on chemistry, materia medica, pharmacy and botany; on anatomy and physiology; on the theory and practice of medicine. If these were passed successfully, the Latin papers on a medical case and an aphorism of Hippocrates followed.53

Student numbers grew rapidly during the French wars as doctors were trained to serve with the armed forces and by 1810 there were around 300 medical students from all parts of Britain. Many still used the university medical classes to complement their training as apprentices and the high flyers moved around the medical schools to learn from the best practitioners of the day.54

Further reading: Advancing with the Army Medicine, the Professions and Social Mobility in the British Isles 1790-1850

Marcus Ackroyd, Laurence Brockliss, Michael Moss, Kate Retford, and John Stevenson

Progress continued and the curriculum was extended to include a compulsory course on midwifery and a course of surgery (unless the candidate had attended three course in anatomy). In 1817, following Burns' appointment, the anatomical substitute was abolished. In 1824, two years attendance at hospital was required and in 1826, four years of medical study.55

Old College Life

Students found time for extra curricular activities. The Medico-Chirurgical Society was founded in 1802. In 1836, two anatomy students brought out the first student periodical called 'The Scalpel' but its name and content was found offensive by the University and it was discontinued.

AKH Boyd describes life as a student or a 'Colley doug' in the Old College. He was one of 'a host of lads varying in age from decided boyhood to decided manhood, conspicuous by the 'scarlet mantle they wear'. To gain entry to a class the student called upon the professor in his house and paid a fee of mostly three guineas for a ticket of admission to the classroom. At the end of the session, the professor wrote a certificate of the student's attendance.

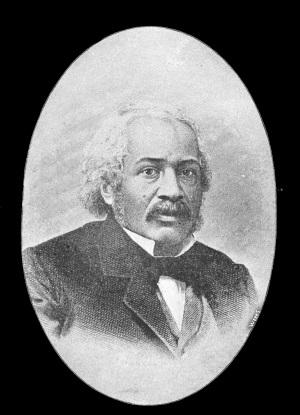

James McCune Smith

Amongst the students was the first African American known to have studied at the University, James McCune Smith. He graduated MD in 1837. While studying in Glasgow he worked with the Glasgow Emancipation Society.

Amongst the students was the first African American known to have studied at the University, James McCune Smith. He graduated MD in 1837. While studying in Glasgow he worked with the Glasgow Emancipation Society.

The James McCune Smith Learning Centre opened in April 2021

Hunterian Museum

Hunterian Museum

The Hunterian Museum, designed by William Stark was completed in 1804 to house the magnificent collection of books, manuscripts, coins, medical materials and other items bequeathed to the University in 1783 by William Hunter.60

Amongst the varied collections were his anatomical and pathological preparations which were and are still a valued teaching resource today and now housed in the Allen Thomson Building at Gilmorehill and at the Royal Infirmary, Glasgow.61

Pioneers in the development of the Medical School

The development of the medical school of the University owed much to a determined group of pioneers. The brothers Allan were skilful anatomists. John Burns had introduced surgery into the curriculum, essential in military service where amputations were common, and became the first professor of surgery in 1815. In the same year, James Towers became the first professor of midwifery and laid the foundations of hospital medical care in the city. The Crown established further chairs, in materia medica, physiology and forensic medicine, in the 1830s.

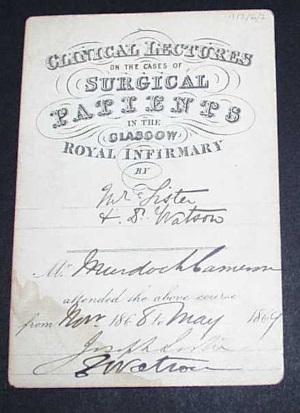

Joseph Lister

A major change began with the appointment of Joseph Lister as Professor of Surgery in 1860. He experimented with the use of carbolic acid to prevent the spread of infection in wounds, the main cause of many post-operative deaths. The first patient to be successfully treated for a compound fracture (where the bone perforated the skin) was James Greenlees in August 1865. This achievement placed Glasgow at the forefront of modern surgery.62

The man in the white coat (and his dog)

As a 'raw and lanky junior student', influenced by the lectures of Joseph Lister on the discoveries of Louis Pasteur, Sir William Macewen had been affected by conditions on the wards at Glasgow Royal Infirmary where the odour of flesh wounds caused him to faint. An elderly nurse showed him a patient with a wound healing successfully and he began to realise the factors involved in the prevention of infection and develop his techniques in asepsis.63 He had also worked as a surgical dresser for Joseph Lister.64

From his early days as a student, and heedless of the derision of others, Macewen had worn a white overall during his early operations. This was quite an improvement on a black morning coat, caked with blood, and he impressed the nursing staff so much that they bought him a fish kettle to sterilise his instruments.65

He had a personality to match his professional skill. In 1874, he became the first medical superintendent of the new City Fever Hospital at Belvidere. There, his retriever Leo accompanied him on his visits to the children's wards, with Sir William's inkwell attached to his collar. His dog was very popular. Unfortunately, Leo disappeared; a victim of notorious dog thieves who ranged the streets picking up valuable dogs and selling them on to unsuspecting buyers.

Leo was lost for several weeks until, on returning home one evening, Sir William went into a shop and heard the scratching and whining of an excited dog under the counter. The lady shop owner had bought the dog as a companion for her invalid sister and refused to give him to Macewen, who recognised Leo. The matter was resolved by a policeman called in to the shop. If the gentleman should walk away and the dog was his, he would follow his master. Needless to say, Leo did. However, the next day the lady pleaded in tears for the return of Leo and he was duly returned.66 Nowadays, the healing power of pets is recognised in the work of voluntary organisations such as Pets as Therapy.67

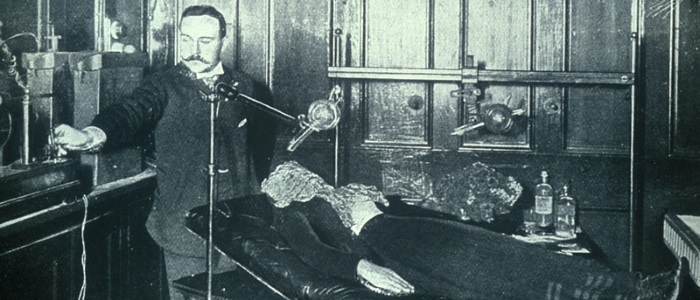

John Macintyre's X-Ray Department

Towards the end of the century, John Macintyre, who had graduated MB, CM from Glasgow in 1882, opened the world's first hospital X-ray or Radiology Department at Glasgow Royal Infirmary in 1896. His lab made an important breakthrough, the first X-ray cinematograph of the legs of a frog. By 1901, X-rays were being used on patients and successfully helping to diagnose and treat a variety of illnesses and injuries.68

View the first X-ray cinematograph film ever taken, at Glasgow Royal Infirmary, and presented by Dr John Macintyre at the London Royal Society.

Macintyre's X-ray cinematograph (1897, Scottish Screen Archive). Film from Glasgow Royal Infirmary's archive collections, Medical Illustration Services

john macintyre's achievements

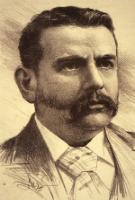

John Macintyre

Pioneer Radiologist (1857- 1928)

Medical electrician

First X Ray

Glasgow Royal Infirmary

Some other firsts

Macintyre's methods

Bones and joints

Soft tissue radiography

More pioneering radiography

Parlour Maid's Knee

Early health and safety

Teacher

The man himself

Becoming a Doctor

A long and bitter dispute with the Faculty of Physicians and Surgeons in Glasgow over the right to license doctors to practise was resolved69 when the Medical Act of 1858 made a diploma, degree or licence granted by one of the recognised examining bodies a prerequisite for admission to the Medical Register and entitlement to practise in any part of the country and charge a fee.

The General Medical Council, created by the Act, had the duty of overseeing the standards of medical education. The student had to pass examinations and obtain a diploma, degree or licence from a qualifying institution approved by the General Medical Council.

In 1884, the Royal College of Physicians in Edinburgh, the Royal College of Surgeons in Edinburgh and the then Faculty of Physicians and Surgeons united to grant a 'Triple Qualification'. The holder could register three diplomas under the Medical Act.

The Commissioners appointed under the Universities (Scotland) Act drew up ordinances that in 1860 instituted the degrees of Bachelor of Medicine (MB) and Master of Surgery (CM). These were conferred after four years of study of a specified curriculum and a successful examination. Subsequently, as a result of another Universities (Scotland) Act, from October 1892, the course was extended to five years and the degrees conferred on graduation became the Bachelor of Medicine (MB) and the Bachelor of Surgery (ChB). The Master of Surgery (ChM) joined the MD as a higher qualification.70

The University moves to Gilmorehill

By the 1840s, the old college buildings were inadequate for the number of students. There was more than enough land to rebuild on the same site, but an increasing population, decay of the houses and industrial pollution was making the High Street increasingly unpleasant. In 1863 the Glasgow Union Railway Company offered £100,000 for the college site. This was accepted and the 43-acre site at Gilmorehill bought for £65,000.71

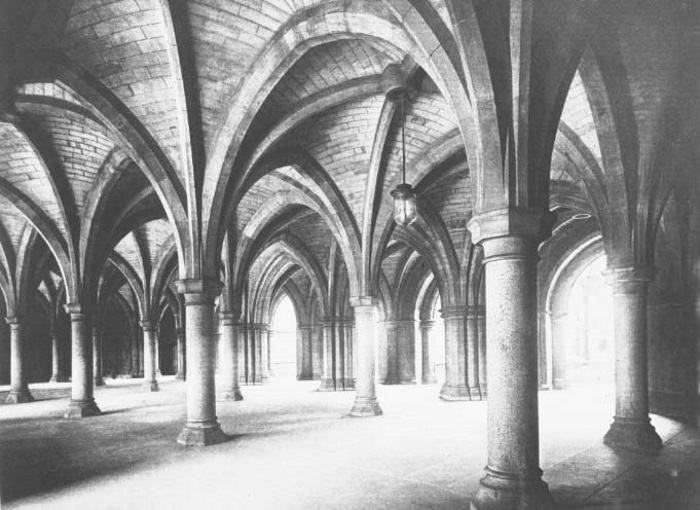

The new buildings at Gilmorehill, designed by Gilbert Scott and similar in plan to the Old College but built on a grander scale and in a gothic style, were formally opened by the Chancellor, the Duke of Montrose, on 7 November 1870. The science and medical departments were housed in the east quadrangle. The Hunterian Museum was moved to the central section of the north front and can be visited today.72 There were by now almost 1,300 students in four faculties. There were 160 graduates, including 106 in medicine and 37 in arts. The new teaching hospital, the Western Infirmary, was opened four years later in 1874 in the grounds of where the Glasgow Art Galleries now stand.73,74

Clinical teaching at Gilmorehill – the Western Infirmary

The building of the hospital was slow. While systematic lectures were given from 1870 in Gilmorehill in the new University buildings, clinical teaching continued in the morning at the Royal Infirmary as before. Buses were arranged to transport the not-always-well-behaved medical students from the Royal Infirmary to the University. Pedestrians and shopkeepers occasionally made complaints about their conduct to their teachers.75

Read some regulations from the Glasgow Royal Infirmary for students, nurses and patients!

Further developments

Four senior clinical appointments were made. The senior physician was William (later Sir William) T Gairdner, Regius Professor of Medicine, regarded as one of the finest teachers of his day. Thomas (later Sir Thomas) McCall Anderson, Professor of Clinical Medicine, and came from an old Glasgow family of whom many members had been prominent in the life of the city. George (later Sir George) HB McLeod, who had succeeded Lister as Regius Professor of Surgery, was the senior surgeon, a meticulous surgeon, fine teacher and apparently an outstandingly handsome man. The second surgeon was Professor of Clinical Surgery George Buchanan, who had also served in the Crimean War and was short and stout. An aged five-inch-deep tree trunk which he used as an operating stool was referred to as 'Geordie Buchanan's cheese'.

Further wards were opened and more chiefs were appointed. Three eminent dispensary physicians were appointed: Gavin Tennant, Joseph Coates (pathologist, founder of the Pathological Institute and occupant of the first chair of Pathology from 1894), and David C McVail, the infirmary vaccinator (later a physician to the Royal Infirmary, Professor of Medicine in St Mungo's College and the Crown's representative from Scotland on the General Medical Council). 76

1n 1877, more specialised departments had opened, including the Ear, Nose and Throat department, which united the separate specialities under the lectureship of William S Syme (an Edinburgh graduate, originally from Newfoundland) and a department for diseases of women which was under the charge of William Leishman, Professor of Midwifery. Leishman had been physician to the University Lying-In Hospital and Dispensary (maternity), which had been established in the neighbourhood of the Old College many years previously (read more).

William Reid was appointed visiting physician in 1894 when Leishman retired. Reid had qualified in 1866 and had worked in general practice before being appointed lecturer in clinical obstetrics, becoming chief in 1892. He was regarded as a pioneer in obstetrics,77 had introduced new implements for use in obstetrics and had attended at Rottenrow with Murdoch Cameron, an obstetrician responsible for the revival and development of the caesarean section at Rottenrow.78,79

By 1878, the Western Infirmary was completed, with a £40,000 donation from the will of John Freeland of Nice, elder son of the founder of a Glasgow firm which traded with the West Indies.80 By the end of 1883, it was in operation, with a total of 346 beds. Funding for the Western, a voluntary hospital, was derived principally from annual subscriptions and from the contributions of employees in public works, warehouses and offices. A small sum from the wages of employees of the major works and shipyards was deducted on payday, thus providing a community of interest between the infirmary and many of its patients. Donations fluctuated with periods of commercial prosperity and depression in the city and with the benevolence of individual donors. Interest from invested funds and students' fees added a significant sum. A student's hospital ticket would cost him ten guineas a year at this time.81

The Samaritan Society was founded in 1875 to assist poor patients and their families. They supplied clothes and other comforts to patients when they left hospital, keeping in touch with them and helping to find them employment.82

For over 20 years at the Western Infirmary, there was only one theatre, which was used both for surgical operations and for lectures. Its semi-circle of benches could hold an audience of 300. Most would not have a very good view of the proceedings, apart from some of the athletic performances entailed in the reduction of fractures and dislocations. Operations had to be confined to the readily accessible parts of the body and the results were remarkably good, considering that the surgeons had to work with a fixed operating table, gaslight and other elementary facilities. By 1890, the number of operations performed had increased from 235 to 877 in the first year of the hospital.83

One of the main purposes of the Western Infirmary was to provide clinical teaching close to the University in its new location on Gilmorehill. The original four chiefs had held similar clinical appointments and chairs in the Royal Infirmary and had included the Regius Professors of Medicine and Surgery. The subsequently established Chair of Pathology carried an associated appointment as Pathologist to the Western Infirmary. Chairs in Medicine and Surgery were re-established in the Royal Infirmary in 1911 and the Chairs in Clinical Medicine and Clinical Surgery suppressed at the Western Infirmary. Students had to seek their clinical teaching in one or other of these hospitals. Most clinical teachers were conscientious and appreciative of introducing the student to his or her first personal contact with patients.84

Prof Lawrie remembers his first days as a house officer at casualty.

"I remember the first time I started at the Royal Infirmary, and you had to go down to what's now the accident and emergency or what was called the Gatehouse at the Royal Infirmary, to see the acute cases as they came in. And if you thought they were ill enough you moved them up to the ward. And I can remember I went down with another doctor and this individual, I think it was a man who came in gasping for breath, sitting bolt upright, blue in the face. I thought I could make the diagnosis, but I had a great difficulty in remembering treatment. I was almost, not quite paralysed, but it showed me all the difference between book knowledge and practical knowledge. I mean if somebody had said to me, "this man is suffering from acute left heart failure, what's the treatment?", well, I could've run it through from the textbook. But when you saw the patient, what did you do? What did you give him? It took me a long time to adjust from book knowledge to practical knowledge and treating the patient."85

St Mungo's Medical School

The growth of the medical school also owed much to the close proximity of the college and the Royal Infirmary and when the University moved to Gilmorehill in 1870 and the medical chairs transferred there, the Royal, disappointed, established its own medical school, St Mungo's College of Medicine, and relations did not resume with the University until the first decade of the 20th century when the Muirhead chair and others were founded.86

Much healthy rivalry still exists between the two hospitals today, as a former student recalls.

"But you know you were in the Royal Infirmary or the Western Infirmary or wherever you were, was your hospital, it was your base, and you very jealously regarded its privileges and positions. And you would scurrilously refer to the Western Infirmary if you worked in the Royal as 'the cottage hospital off Argyle Street'. Or if you were in the Western, the Royal used to be called 'the slum off Alexandra Parade'".87

Women in the Faculty of Medicine

Women in the Faculty of Medicine

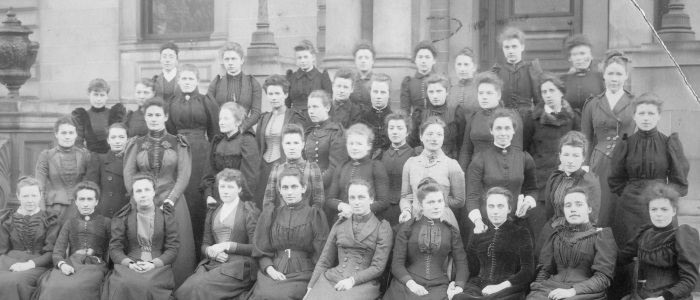

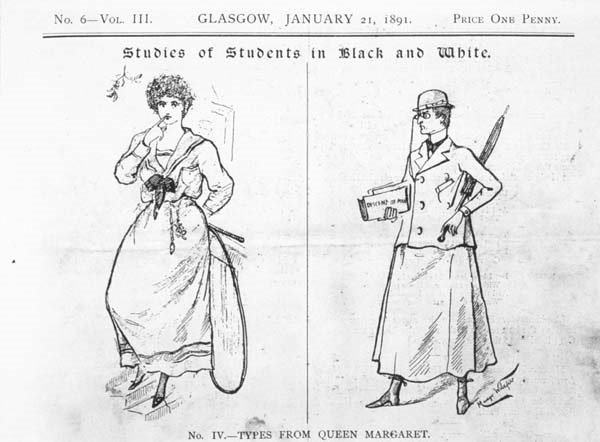

The emergence of St Mungo's College was paralleled by moves to provide medical education for women in Glasgow. The two could not be combined at the time due to irreconcilable social attitudes. Separate facilities for women were arranged in the recently established Queen Margaret College in 1883.

Queen Margaret College

Queen Margaret College was the first institution to provide a comprehensive programme of higher education for women in Glasgow. Even after the Universities Act of 1889 removed all remaining legal restraints, the University consistently refused to admit female students to any of its classes. Responsibilities for the college passed to the University in 1892.88

The College was unique in Scotland as a women's college that offered university-level teaching in both arts and medicine. In the UK, it was the fourth centre for female medical students after London, Dublin and Edinburgh.

In its first session it had 13 medical students (131 students in arts), including nine novices and four medical missionary students who, having studied elsewhere, took second-year classes. The sessions, class fees and regulations were identical to those of the University. Some of the lecturers were members of the University medical staff, who were simultaneously giving the same instruction to men on Gilmorehill, and the others were all Glasgow graduates or lecturers in other extramural medical schools. Clinical instruction was provided in two wards of the Royal Infirmary which were reserved for QMC students.89

Until the 20th century, the only mixed classes were Dr Yellowlees’ lectures on insanity at Gartnavel Royal Lunatic Asylum. Being in separate classes, the women were initially denied professorial teaching. In 1894–95, the women shared the same teachers as the men only in five subjects, namely zoology, physiology and practical physiology, midwifery, forensic medicine and insanity.90

Problems also arose for women when they attempted to gain experience of practical work. Resistance to clinical facilities was encountered. An application was refused outright by the Western, shelved by the Victoria and given limited approval by the maternity hospital. The reasons given were varied; teachers and facilities were taken up by the needs of male students, and the hospitals had no physical facilities to cater for females – no cloakrooms, toilets or recreational amenities – though they all possessed a female nursing staff. The most significant argument was that their mental capacity, poor standard of education and the social 'delicacy' of the female sex made them poor material for medical training.91

Female students and doctors found it easier to gain access to hospitals with women or children's diseases. In 1890, Glasgow Sick Children's Hospital admitted female students and by 1892 had 12 QMC students and two male students working in its wards.92

First women medical graduates

The first women medical graduates from Glasgow, or indeed any Scottish university, were Marion Gilchrist and Alice Louisa Cumming. They graduated in medicine in July 1894.93

The range of women's medical work continued to widen slowly. Female students were a different type of student; women were more mature in age and from a socially superior class. They tended to treat other women and children (apart from the paupers of the workhouse) till 1914 and the First World War.94

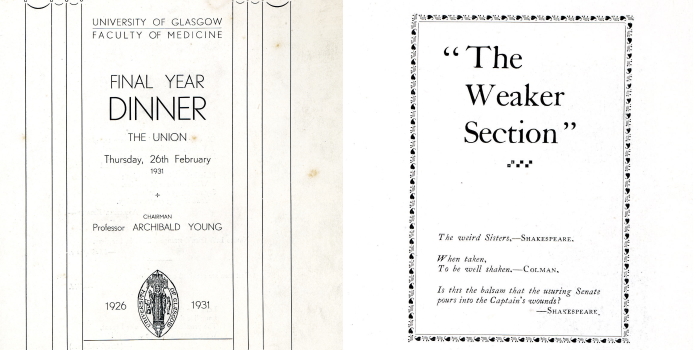

A graduate from 1949 recalls that "there were about 42 women to start with and about 140 men. The final dinner which the women had was separate from the men and the events were held on the same night in their respective student unions".95

Progress in academic medicine was to come some years later when the first female professor was appointed in 1978.

Professor Jackie Taylor, a Glasgow graduate, became the first female President of the Royal College of Physicians & Surgeons of Glasgow in 2018.