Neurosciences

Clinical Neurosciences

Injuries and diseases of the nervous system cause many early deaths and long lasting disability and have a relatively high incidence in Scotland. In the second half of the last century, partnerships between the University and Health Services across the neurosciences in Glasgow, produced advances in knowledge and care that improved patients’ outcomes locally and became renowned internationally.

Specialisation in disorders of the nervous system began in Glasgow in the 1930s but initially depended on isolated clinicians with part time interests. Full-time specialists in neurosurgery, Mr Sloan Robertson, and neurology, Dr John Gaylor, were appointed to the Western infirmary in 1941.

At the same time, the University, through Principal Sir Hector Hetherington and Regius Professor of Surgery Sir Charles Illingworth, catalysed cooperation between the four Glasgow teaching hospitals, the Glasgow Corporation, and the Scottish Health Department.

This resulted in all neurosurgery being centralised in 1942 at the Emergency Medical Services hospital at Killearn, in a new unit led by Robertson, Mr Eric Paterson as a second neurosurgeon, and Gaylor as visiting neurologist.

The subsequent decades saw the emergence of increasing numbers of clinicians across several specialities wholly devoted to the diagnosis and treatment of people with afflictions of the nervous system. The creation of an Institute of Neurological Sciences (INS) as a joint initiative between the University and Western Regional Hospital Board brought these together, first at Killearn hospital in 1966, and then in 1970 at the Southern General Hospital. These arrangements were then unique in the UK outside London and became the model for many others.

The key person in these developments was Robertson. In 1939, he had spent a year with Dr Wilder Penfield in Montreal, Canada, where he saw the benefits of an Institute in which all the diagnostic and therapeutic elements required for the investigation and treatment of neurological diseases and injuries were located together on the campus of a general hospital.

The site at Killearn had been intended to be a temporary step and it became increasingly clear that its facilities were inadequate and its location inappropriate. Robertson, strongly supported by Mr Alistair Paterson who had also trained in Montreal, was intent on creating a Montreal model in Glasgow.

For several years, they steadfastly resisted invitations to divide the unit between the Glasgow hospitals and risk isolation from other neurological specialities. Eventually in 1970, Robertson’s ambition was achieved when the Glasgow unit moved into the new Institute of Neurological Sciences (INS) building at the Southern General Hospital.

The opening by Queen Elizabeth in 1992 of a new National Spinal Injuries unit alongside the INS completed the picture.

The University began to invest in neurosciences through the appointment of a neurosurgeon jointly with the NHS in 1963. It went on to create chairs in Neurology in 1964, in Neurosurgery in 1969 and in Neuropathology in 1971. These were first held by Iain Simpson, Bryan Jennett and Hume Adams respectively. The INS accommodated their departments along with divisions of neuroanaesthesia, neuroradiology, neurophysiology, and clinical physics, with visiting specialists in neuro-ophthalmology, neuro-otology and neuro-oncology.

The character of the INS was expressed in an inter- and multidisciplinary, academic and clinical approach that enabled it to be at the forefront of developments in clinical care. Thus, it was able to bring the world’s second computerised tomography (CT) scanner (1974) and the first magnetic resonance (MR) imager dedicated to neurosciences (1984) to Glasgow for evaluation and research (see Radiology). Close links with laboratory scientists fostered ground-breaking translational research.

The University departments gained substantial support for their research from leading sources including the Wellcome Trust, the Scottish Home and Health Department, the National Institutes of Health USA, and many charities. The Medical Research Council was a major source of support over many years and, in 1999, its award of much sought after MRC Co-operative Group Status to researchers in Neurosurgery, Neurology, Neuropathology and at the Wellcome Surgical Institute was an eloquent and practical recognition of the fulfilment of Robertson’s vision.

The four University departments were formally brought together by the University Faculty of Medicine in a Division of Neurosciences in 2002.

After the retirements of Teasdale in 2003, Graham in 2005 and Kennedy in 2016, the established chairs in Neurosurgery, Neuropathology and Neurology were not directly replaced. Instead, research leadership and achievement have been recognised through the award of Professorships personally to Hugh Willison (Neuro Immunology and Neurology ), Donald Grosset (Neurology), William Stewart (Neuropathology) and the appointment of Keith Muir to the SINAPSE Chair of Clinical Imaging .

At the beginning of the 21st Century, reorganisation in the NHS saw the management of the INS clinical departments increasingly merging with regional and general divisions in the Greater Glasgow and Clyde Health Board.

The scale of expansion in its services to the West of Scotland is reflected in the Institute’s consultant complement having grown from the handful of pioneers at Killearn to a total of more than 50, comprising of -

- 20 neurologists,

- 10 neurosurgeons,

- 3 neuropathologists,

- 7 neuroradiologists,

- 4 neurophysiologists

- 13 neuro anaesthetists

Penfield is 5th from left front row, Sloan Robertson on his left. To Penfield’s left are Brian Jennett (Neurosurgery), Iain Simpson and Ian Melville (Neurology) and John Barker (Neuroanaesthesia).To Robertson’s left are Alistair Paterson (Neurosurgery), Leslie Stevens (Neuroradiology), John Hume Adams (Neuropathology)and Donald Grossart (Neuroradiology).

In the row behind are David Doyle (Neuropathology), Douglas Miller John Turner( Neurosurgery), William Fitch (Neuroanaesthesia), Thomas Hide (Neurosurgery), Peter Macpherson (Neuroradiology) and John Russell (Neurosurgery).

Professor Sir Graham Teasdale

Neurology

Neurology in Glasgow developed as a specialised subject during the inter-war and World War II periods. In 1941, John Gaylor was appointed as neurologist at the Western Infirmary, and became the first lecturer in neurology at the University of Glasgow. After World War II, Stewart Renfrew was appointed as neurologist to the Royal Infirmary, and Joly Dixon to the Victoria Infirmary, Stobhill and Southern General hospitals.

Iain Simpson

The Chair of Neurology at Glasgow University was founded in 1964. John (known as Iain) Alexander Simpson (1922-2009) was appointed the first Professor of Neurology (1964-1987).

He was based at the Western Infirmary, with beds at Knightswood Hospital. Ian Melville and Ivan Draper were appointed as consultant neurologists in 1965, also based at the Western Infirmary, with beds at Knightswood Hospital.

At this time, plans for a Neurosciences Institute were being made by the Regional Board and the University of Glasgow. In 1966, the Institute of Neurological Sciences, Glasgow (INS) opened at Killearn, with beds and new research and laboratory facilities. The Institute moved to new-build premises at the Southern General Hospital in 1970, with Neurology as one of the five academic departments.

A steady succession of trainees came to Simpson’s department, with interests in immunology and electrodiagnosis, from the USA, Australia, Canada, Spain, and India. There was a large teaching remit, undergraduate and postgraduate, and for nurses and speech therapists. The University department expanded with the appointments of Peter Behan, Ralph Johnston, and later Peter Kennedy and Hugh Willison as senior lecturers.

Simpson created “one of the most impressive and outstanding departments of clinical neurological science, not only in the United Kingdom but anywhere in the world.” (Festschrift, Lord Walton.)

He became the international authority on myasthenia gravis after he observed its association of with other autoimmune diseases, and put forward his autoimmune hypothesis, Myasthenia Gravis as an Autoimmune Disease, published in the Scottish Medical Journal in 1966. He was Chairman of the Scottish Council for Neurological Services and of the Scottish Epilepsy Association, and a member of the Research Committee of the Muscular Dystrophy Group of Great Britain.

He also studied the chorea related to hypothyroidism, the dermatological alterations and hypocalcaemia, as well as a number of findings related to abnormal nerve conduction velocities. He was among the first who noted the neurophysiological abnormalities of the Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome, and was editor of the Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry.

Iain Simpson, before he retired, continued to be interested and participate in studies on myasthenia gravis. In 1974, Peter Behan joined the department and organised studies involving immunological aspects of muscle and nervous disorders.

He demonstrated clustering of immune response genes in myasthenia, and a clinical response of patients with myasthenia gravis to courses of plasma exchange, one of the main forms of treatment. He showed that the condition known as acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM), which hitherto had been considered a form of multiple sclerosis, was an entirely different disorder and the mechanism was hypersensitivity (of the delayed type) to encephalitogenic protein. He also demonstrated a specific immunological syndrome in patients taking practolol, one of the first beta blocker drugs.

Peter Behan

Peter Behan (Professor of Neurology, 1989) published many papers on multiple sclerosis, starting with a study of the association of multiple sclerosis with hypertrophic neuropathy (Brain (1977) 100; 755–773).

He demonstrated relationships between multiple sclerosis and different forms of trauma; and the brain lesions associated with septic shock. He drew attention to left-handedness and altered dominance in patients with immune disease and developmental learning disorders; and also to the altered dominance found with childhood autism, developmental dyslexia and other immune disorders.

His work on post-viral fatigue syndrome is well known and his paper ( ‘Fatigue in Neurological Disorders’ -The Lancet (2004), is one of the most cited from the department. His study on idiopathic coma (The clinical spectrum, diagnosis, pathogenesis and treatment of Hashimoto’s Encephalopathy: recurrent acute disseminated encephalomyelitis’ (2003) is also much cited.

Behan was Editor of the International Journal of Neuroimmunology, and was on the advisory committee of neuroimmunology to the World Federation of Neurology. He was a member of the International Workshop on Multiple Sclerosis and a member of the Scientific Committee of NATO. He received many awards, including

- The Pattison Prize and Medal 1985

- The Dyslexia Society Award

- The Melville Ramsay Medal and lectureship

- The Dutch International Award for Neurological Causes of Fatigue

- Doctors Heather Cavanagh and Abhijit Chaudhuri, both lecturers under Behan, received respectively the Sir William Dunn gold medal of the Royal College of Physicians in 1997, and the inaugural Pfizer Prize given at the World International Meeting of Neuropsychiatry in 1997. Dr Chaudhuri further received the Ramsay Medal and lectureship in 2002.

Professor Behan’s research was done in close collaboration with his late wife, Professor Mina Behan (Professor of Muscle Pathology, 2000). Her contributions were seminal and important. She was an author on virtually all of his publications. Both Peter and Mina Behan were active teachers and ran courses at the university.

Peter Kennedy

Peter Kennedy succeeded Iain Simpson and was the first Burton Professor of Neurology (1987-2016). Under Kennedy’s leadership, the scientific base of the department rapidly flourished with a significant increase in the number of laboratories, clinical and scientific personnel, and grant income.

His research, which is ongoing, has focused on viral infections of the nervous system, including pioneering studies of Varicella-Zoster virus latency, defining viral location and gene expression during human ganglionic latency. He soon undertook research into human African trypanosomiasis (sleeping sickness), culminating in the recent development of a promising new therapy for CNS sleeping sickness.

His earlier studies in developing cell-type specific markers for human brain cells have been of great relevance as precursors to current trials of human neural stem-cell therapy for neurological diseases. He has received several research awards including the CBE for 'services to clinical science' in 2010.

Ian Bone (Honorary Professor 1998) established with Donald Grosset a neurology-led acute stroke unit, and published on a range of neurological conditions. With Sam Galbraith (Neurosurgeon), he instituted the initial West of Scotland epilepsy surgery programme. He edited a training journal for UK trainees, advised the Scottish Government on neurology services, and brought the first international neurology conference to Glasgow (European Federation of Neurological Sciences, 2006). Latterly, he was funded by the Medical Research Council to investigate novel treatment in Prion Disease.

Roderick Duncan (NHS consultant 1993-2012) developed an international standard epilepsy surgery programme, introducing intracranial stereotactic EEG recordings, with a research programme in ictal HMPAO SPECT scanning. He developed a major clinical service and research programme in psychogenic seizures, the latter largely defining current knowledge of their epidemiology. He went on to become a member of the International League Against Epilepsy psychogenic seizures task force and its psychiatry commission.

Hugh Willison is Professor of Neurology (2002-current). He leads the Neuroimmunology Research Group within the Glasgow Biomedical Research Centre. The group researches the pathogenesis of autoimmune neuropathy, principally funded by the Wellcome Trust. The emphasis is on the role of anti-ganglionic antibodies in the post-infectious paralytic neuropathies.

Keith Muir joined the Department of Neurology in 1995 after undertaking research at the recently-established stroke unit at the Western Infirmary, was Senior Lecturer in Neurology from 2001-09, and currently holds the SINAPSE Chair of Clinical Imaging (Stroke and Brain imaging). His major interests are in application of advanced imaging to translational research in acute stroke, and have included the development of novel thrombolytic drug treatment and endovascular clot removal in acute stroke, the world’s first clinical trial of human neural stem cell treatment in chronic stroke, and trials evaluating the utility of advanced imaging in patient management, with support from a range of bodies including the European Union, MRC, Wellcome Trust, CSO, National Institute of Health Research and the Stroke Association.

He also led the development of the Imaging Centre of Excellence (ICE) project that brought ultra-high field MRI (Scotland’s only 7T scanner) to the Queen Elizabeth University Hospital campus, opening in 2017, and planned to be a focus for development of clinical application of 7T MRI.

Donald Grosset (Honorary Professor 2015) leads Tracking Parkinson’s, a major UK natural history and genetics study. Research highlights are the detection of emboli with ultrasound, the pivotal studies of FPCIT-SPECT (DaTSCAN) as a diagnostic imaging test, and award-winning studies on therapy adherence in Parkinson’s Disease.

From the 1990s, the increasing burden of stroke in the older population, and the demonstration that acute stroke units improved stroke outcomes through rapid diagnosis and treatment, saw the evolution of Stroke Medicine as a specialty. Stroke is considered in a separate section (see Stroke).

Ian Melville and Peter O Behan

Images provided by Peter Behan

Neuropathology

The University input to Neuropathology began in 1961 when J Hume Adams took over the service at Killearn hospital from an NHS consultant, Dr Margaret Leslie. In 1962, Hume Adams was appointed Lecturer and in 1969 promoted Reader in Neuropathology. The University Department was established as an independent part of the Department of Pathology at the Western Infirmary.

Laboratory facilities were provided at Killearn Hospital and, in 1970, at the Southern General Hospital, as part of the Institute of Neurological Sciences (INS). Hume Adams was promoted in 1969 to Titular Professor and retired in 1994. In 1968, Dr David I Graham was appointed Lecturer in Neuropathology and subsequently became Titular Professor (1983): he retired in 2005. Dr JAR Nichol was appointed Senior Lecturer in October 1992 and achieved a personal professorship in August 2001, before taking up the post of Chair in Neuropathology, University of Southampton. Additional NHS staff were appointed in 1971 (Dr D Doyle), in 2002 (Dr Susan Robinson) and in 2006 (Dr W Stewart).

Service, Training and Teaching

The Department provided a diagnostic laboratory service (biopsy, CSF cytology and post mortem) for the clinicians of the INS and a regional service for the hospitals in west-central Scotland. This provided material for teaching and research, and was the basis of audit and clinico-pathological correlation. Many pathologists and clinicians from the UK and abroad visited the Department and all junior pathologists rotated through the Department for periods of training.

Specialist provision developed with the establishment of peripheral nerve and muscle biopsy and paediatric expertise (Dr D Doyle) and the application of molecular techniques to specific treatment of brain tumours (Professor JAR Nichol linked to Mr V Papanastassiou and Professor R Rampling). The regional morbid anatomical workload was shared, although specialist interest developed in the provision of forensic services by Professor Graham.

In the first decade of the new Millennium, after a series of reorganisation of NHS services, in 2012 Neuropathology became part of the Diagnostic Directorate of Greater Glasgow and Clyde Health Board and was relocated to a purpose built Laboratory Medicine Building on the Southern General Hospital site as part of the Queen Elizabeth University Teaching Hospital.

Research

The Department, over a 30 year period, gained international recognition for its expertise in the pathology of acute brain damage. It developed unique datasets, with Professor I Ford and Dr Lillian Murray (Robertson Centre for Biostatistics) bringing together information from clinical, neuropathological and laboratory studies. Close association with the Department of Forensic Medicine and Science (Professor G Forbes and P Vanezis) made possible unusually comprehensive neuropathological examinations. The findings from these studies led to major advances in knowledge of head injury and 'stroke'.

Head Injury

The Department closely collaborated with the University Department of Neurosurgery in Glasgow (Professor BW Jennett and Professor Sir Graham Teasdale) and Philadelphia (Professor TA Gennarelli). This led to the what became internationally known as the Glasgow Pathology dataset, which made possible clinico-pathological correlations that advanced understanding of events after a head injury, their consequences and management.

Frequency and types of traumatic brain injury

A distinction was established between ’primary’ lesions likely to occur at the time of injury, such as contusions and damage to white matter tracts, and ‘secondary’ lesions such as raised intracranial pressure and ischaemic damage. The techniques developed to quantify them led to standardised grading systems.

Patterns of ischaemic damage

A seminal observation was the totally unexpected finding of a high frequency of secondary damage to the brain as a result of reductions in cerebral blood flow. Greeted by an element of disbelief by clinicians, studies in critical care units quickly confirmed the post mortem observations and identified the damage as potentially 'avoidable/preventable'. This was a landmark finding that changed clinical practice and improved outcome after head injury.

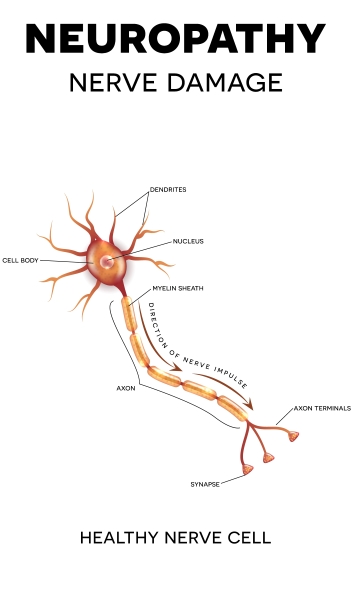

Diffuse traumatic axonal injury

Another seminal contribution was that immediate unconsciousness was related to widely distributed damage to myelinated axons in the brain. Laboratory studies in collaboration with the Departments of Neurosurgery (Professors TW Langfitt, TA Gennarelli) and Bio-engineering (Professor L Thibault) of the University of Pennsylvania showed that such damage was a consequence of movement of the brain in the head and could develop in the absence of impact either to or of the head.

This phenomenon became known throughout the world as DAI (Diffuse Axonal Injury). Grades of damage were identified (Dr W Maxwell, Department of Anatomy) to allow standardisation, and the most severe were shown to be the principal cause of the vegetative state.

A genetic influence on outcome and possible links to Alzheimer's Disease

Similarities in the pathology of acutely head-injured patients in some professional sportsmen and those dying with Alzheimer's Disease were identified. Linkage through the polymorphism of the ApoE gene was identified as a possible common factor in longitudinal clinical studies (see more in Neurosurgery). An association with chronic traumatic encephalopathy is an ongoing interest (Dr W Stewart). Collaborative studies identified cytokines as a possible mechanism (Professor S Griffin - University of Arkansas and S Gentleman -Charing Cross Medical School, London). Changes in neurotransmitter distribution were shown in a tissue bank of material donated by patients with Alzheimer's Disease (Dr D Dewar Wellcome Surgical Institute, WSI ).

Stroke – related Brain Damage

Laboratory investigation of patterns of ischaemic damage

The Department, together with colleagues in neurosurgery and neuroscience at the Wellcome Surgical Institute (WSI) developed a programme of work to investigate the patho-physiology of changes in cerebral blood flow under both normal and simulated pathological conditions (Professors Murray Harper, Mhairi Macrae, and E MacKenzie). The findings showed the importance of the 'ischaemic penumbra'-tissue that was malfunctioning due to reduced blood flow but appeared to be structurally intact.

New models of reproducible ischaemic and haemorrhagic 'stroke'

Models that replicated findings post mortem were developed and their standardisation allowed the amount of damage to be quantified. One of these models, produced by occlusion of the middle cerebral artery in a rodent, became one of the 'gold standards’ in the field.

Protection of the ischaemic penumbra

Pharmacological agents whose receptor mediated action might reduce the amount of structural damage by protecting the penumbra were tested in the models for efficacy. The findings led to pioneering clinical trials, several of which were managed by clinical investigators in stroke units at the Western Infirmary (Kennedy Lees) and the INS (Donald Grosset, Ian Bone and Keith Muir). Although, ultimately, these trials did not lead to drug treatments for 'stroke', the development of trial methodology through the conduct of these studies advanced the concept of 'stroke' as a medical emergency and treatable disease, and contributed directly to the development of effective treatments with thrombolytic drugs, physiological management in stroke units and endovascular thrombectomy.

External Recognition

- Adams was elected Vice -President and then President of the British Neuropathological Society (1979-83) and President of the International Society of Neuropathology (1990-1994). He was awarded a DSc in 1989 and Fellowship of the Royal Society of Edinburgh (RSE) in 1988.

- Graham was elected Fellow of the RSE in 1986, president of the BNS in 1998/99, and of the European Confederation of Neuropathological Societies in 1995. He co-chaired the 2nd International Neurotrauma Symposium in Glasgow and the International Neuropathology Conference, Birmingham, UK in 2000.

- Adams co-edited the 4th and 5th editions of Greenfield's Neuropathology, and Graham the 6th and 7th editions of this principal textbook on Neuropathology. They also co-authored (with D Doyle) Brain Biopsy and An Introduction to Neuropathology.

Professor David I Graham

Nerve cell image from Shutterstock

Neurosurgery

The beginnings

In 1879 in the Royal Infirmary, Sir William Macewen successfully removed an intracranial tumour, diagnosed for the first time only from neurological signs. This marked the birth of modern 'neurological surgery' in Glasgow and throughout the world. Macewen continued his interest in brain surgery while Regius Professor of Surgery from 1882 to 1924 in surgery. Thus, it was only in 1941 that John Sloan Robertson was the first full time neurosurgeon appointed to a Glasgow hospital. After he became head of the new regional service at Killearn Hospital in 1942, his vision for its future drove its growth in scale and complexity.

Its move in 1970 to the new facilities at the Institute of Neurological Sciences (INS) in the Southern General Hospital was the result of Robertson’s persistent commitment. He was appointed OBE in 1971 and died in the Institute from a brain tumour in 1978.

In 1970, the unit covered a population of almost 3 million. It was, with one exception, the busiest unit in Britain. By then, the academic opportunities this offered had been recognised by the University through the appointment in 1963 of an academic consultant jointly with the NHS. This was Bryan Jennett, who became the first Professor of Neurosurgery in 1968 and was the leading academic neurosurgeon of his generation.

Jennett had already published the classic ‘Epilepsy after head injuries’ (1962) followed two years later by ‘Introduction to Neurosurgery’. The fertile environment already existing in Glasgow meant that from the start he could pursue his aim of advancing the scientific basis for neurosurgical clinical practice.

Intracranial haemodynamics and cerebral ischaemia

Early cooperation with anaesthesia (Professor Gordon McDowell, Dr John Barker) showed that inhalational anaesthesia could raise cerebrospinal fluid pressure dangerously. Measurements of intracranial pressure after head injury were shown to identify brain ‘tightness’ (Professor J Douglas Miller) and became standard practice in neuro-intensive care units (NICUs). Cooperation with regional clinical physics (Dr Jack Rowan) and Professor Murray Harper (Wellcome Institute), led to the establishment of an MRC Cerebral Circulation Group in Glasgow from 1970 -1977. This group devised a method for measuring brain blood flow in the operating theatre, and used it to define which patients would or would not tolerate clamping of one of the brain arteries as a treatment for "balloon" weaknesses (aneurysms).

Correlative neuropathological studies with Professors J Hume Adams and David Graham exposed the frequent occurrence of secondary ischaemic brain damage in fatal head injuries. Until then, the view had been that little could be done to alter the fate of a severe head injury but this finding pointed to the possibility that such damage could be avoided and outcome improved by better management. Multidisciplinary clinical and laboratory collaborations aimed at advancing understanding of head injuries and improving their outcome then became the main focus of the department’s research for the next four decades.

Outcome of Brain injury

Jennett's desire to examine the prognosis and quality of survival of severely injured victims led to the delineation in 1972, with neurologist Dr Fred Plum of New York, of the “persistent vegetative state". This was incorporated in the ‘Glasgow Outcome Scale’ , formulated in 1975 with Michael Bond (then Senior Lecturer in Neurosurgery) which is now the standard scale for assessing outcome after a serious head injury. After Bond became Professor of Psychiatry in 1973 (link to Psychiatry Section) he continued to collaborate with Jennett and psychologist Professor N Brooks in identifying the neurological and psychological factors in differing degrees of disability.

In 1980, in the furore that followed a BBC Panorama programme that had challenged the criteria used to establish "brain death" in potential donors, Jennett's clear advocacy of the arguments in the media proved pivotal in sustaining the future of organ transplantation in Britain. In 2002 in ‘The Vegetative State: medical facts, ethical and legal dilemmas ‘, he brought together his efforts to advance understanding and management of severely impaired survivors.

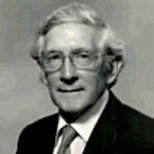

Glasgow Coma Scale

The need for a clinical measure of brain injury to guide early management and to identify late prognosis was fulfilled in 1974 by the delineation, with Graham Teasdale, then Lecturer in Neurosurgery, of the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) (find out more).

The scale was widely welcomed by doctors, nurses and paramedical staff as way to provide a quick, clear and reliable assessment of the conscious state of a patient with a suspected brain injury, the key clinical feature in decisions about management and prognosis. It has provided the common language in guidelines that have brought together developments in specific aspects of treatments to advance management and improve patients’ outcomes all over the world. Teasdale and Jennett’s original description of the scale is the most frequently quoted neurosurgical publication, with more than 5,000 citations in Web of Science by 2014.

A close and fruitful collaboration followed. Jennett and Teasdale co-directed an MRC Head Injury Research programme from 1978 to 1984 and co-authored ‘Management of head injuries’ in 1982. When Jennett became Dean of Medicine 1981- 86, he was succeeded as head of department by Teasdale who was appointed to the Chair after Jennett retired in 1991.

Prognosis of Severe injury

In the 1970s and 80s, international studies of severe injuries, led from Glasgow with NIH funding, established the GCS as the main clinical index in prognosis in acute traumatic and haemorrhagic brain injury. It became a key component of predictive models and comparisons of treatments. Collaborations with statistician Professor Gordon Murray (Robertson Centre for Biostatistics) were crucial in these and many subsequent investigations.

Risk based guidelines

Studies linking epidemiological and neurosurgical data about head injuries established that the GCS identified the risks of early intracranial bleeding requiring urgent operation. Guidelines for acute care, based on the scale, were devised and demonstrated to be effective in Glasgow in 1984. Such guidelines are now used throughout the world and underpin the advances in outcome from modern care.

Non Invasive Imaging

As advances in 3D imaging the brain with CT (1974), MR (1983) and isotopes (SPECT) were established in the INS, they were applied in to advance understanding of traumatic brain damage in collaboration with Neuroradiology (Drs Peter McPherson, Evelyn Teasdale and Donald Hadley (MRC senior fellow, later Honorary Professor) as well as Dr Jack Rowan and Professor David Wyper of Clinical Physics. Features identifying brain swelling and predicting adverse outcome were discovered and became a standard component of severity grading systems; lesions were detected in the white matter in diffuse injury and patterns of ischaemia were shown in life that had been previously seen only post mortem.

New Treatments

In the 1980s and 90s, translational research collaborations by Neurosurgical Senior Lecturers David Mendelow and Ross Bulloch with Neuropathologists (Prof David Graham) and scientists at the Wellcome Institute (Prof James McCulloch) identified the potential for benefit from pharmacological treatments for acute brain insults . Clinical trials confirmed that the calcium antagonist, nimodipine, improved outcome after subarachnoid haemorrhage and it remains standard treatment.

In 1994, Bulloch and Dr Alison Wagstaffe (Neuroanaesthesia) were the first to show that extremely powerful agents blocking neurotransmission could be used safely in comatose head injury victims. A European Brain Injury Consortium of more than 100 neurosurgical and neurocritical care units was founded, and had a powerful influence in ensuring that the subsequent industrially sponsored trials were rigorously conducted.

Disability and death after mild injury

In 1995, the department’s focus broadened from severe cases to head injuries of all degrees of severity. A unique prospective study of a cohort of 3,000 adults admitted to hospital in Glasgow uncovered a previously unrecognised high frequency of long term disability even in victims of what previously would have been viewed as a ‘mild’ injury. Collaboration with psychological medicine (Professor Tom McMillan) showed that the effects could be long lasting and that survivors are also at risk of premature mortality for up to a decade later. The findings stimulated advances in provision of rehabilitation services for head injury.

Genetic effects

In the 1990s, stimulated by findings in experimental models and in the neuropathology of fatal head injury (Professor James Nicholl) seminal clinical studies established for the first time the existence of a genetic influence on outcome of acute head injury. The factor, polymorphism for APO E, also applies in Alzheimer’s disease, but in head injury is expressed most clearly in children.

Brain Cancer

Gliomas are the most common kind of brain tumour and treatments with greater efficacy than radiation and chemotherapy are needed. A Senior Scientist, Moira Brown, in the MRC virology unit in Glasgow identified a variant of the herpes simplex virus that might lyse glioma cells without affecting normal brain. After Dr Brown became Professor of Neurovirology in 1996, the expertise gained in head injury research in the Department of Neurosurgery was used to guide clinical investigations (Senior Lecturers Garth Cruickshanks, Vakis Papanastassiou and Laurence Dunn) with Professor Roy Rampling (Neuro-oncology). In a world first study, the injection of the virus into the brains of people with a recurrent glioma was shown to be safe and potentially beneficial and further development was transferred to a ‘spin out’ company (see Oncology). Professor Brown was later appointed MBE for her contributions.

Service and Training

Neurosurgeons at Killearn were among the first to establish a service based on teams with responsibility for geographically identified areas in the West of Scotland, instead of potentially divisive personal referrals. This promoted the subspecialisation that developed in the 1970s, so that increasingly intricate techniques were taken up in the way that made for the best outcomes for patients. Surgeons in the University team played a full contribution to clinical services, contributing special expertise in pituitary and skull base tumours and in the management of intracranial vascular malformations. In turn, NHS colleagues made important intellectual and practical contributions to teaching and research.

There was free interchange of trainees between NHS and University teams and many undertook research leading to a higher degree.

Glasgow trainees went on to hold the majority of Chairs in Neurosurgery in Britain:

- Edinburgh (Douglas Miller)

- Newcastle (David Mendelow)

- Birmingham (Garth Cruickshank)

- Southampton and then Cambridge (John Pickard)

- London (David Thomas) as well as in Universities in Canada, United States of America, Europe, Australia and Asia

One trainee, Mr Ken W Lindsay, became President of the Association of European Neurosurgical Societies. Another, Mr Sam Galbraith, after a decade as an academically productive NHS consultant in Glasgow, became a member first of all of the Westminster Parliament and then the Scottish Parliament and was Minister for Health and the Arts in the Scottish Office.

External Recognition

Bryan Jennett was a member of the Council of the MRC UK 1979–1983 and of the General Medical Council 1984–91. He was President of the Section of Neurology of the RSM 1986-87, of Headway National Head Injury Patients Group (1988-1995) and of the International Society for Technology Assessment (1987-89). He was appointed CBE in 1991, was awarded an honorary DSc in 1993 by the University of St Andrews, and in 2007 was the first recipient of the Medal of the Society of British Neurological Surgeons.

Graham Teasdale was President of the International Neurotrauma Society (1994 – 98), of the Society of British Neurological Surgeons (2000–2002), and of the Royal College of Physicians of Glasgow (2003–6). He was Chairman of the Senate of Surgery of Great Britain and Ireland (2004–2006). He received the medal of Honour of the World Federation of Neurological Surgeons in 2005 and in 2014 the Distinguished Service Award of the American Academy of Neurological Surgeons. He became a Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh in 2001, and received an honorary DSc from the University of Sunderland in 2013. He was appointed Knight Batchelor in 2003 for services to neurosurgery and victims of head injuries.

Professor Sir Graham Teasdale

Images provided by Professor Sir Graham Teasdale

The Wellcome Institute for Translational Research

Two principles guide biomedical research funding at the beginning of the 21st century: the importance of creating a dynamic research environment with good research infrastructure, and the importance of promoting interactions between basic mechanistic research and clinical practice (multidisciplinary translational research).

In 1960, three far-sighted individuals - Sir Charles Illingworth, Regius Professor of Surgery at the Western Infirmary (see Surgery), Arthur Mackey, St Mungo Professor of Surgery at the Royal Infirmary (see Surgery), and Sir William Weipers, Professor of Veterinary Surgery foresaw the importance of these principles.

They received then huge funding (£50,000) from the Wellcome Trust to build the first dedicated translational institute in a UK medical school (the “Wellcome Laboratory” as it was originally known) and to locate the facility on what was at that time the new, veterinary campus at Garscube, Glasgow.

The opening in October 1960 by the Nobel Laureate Sir Henry Dale, OM was noted in the Lancet and BMJ, and was attended by the Principal, the Secretary of State for Scotland, and the Chief Medical Officer for Scotland inter alia.

The mission of the Wellcome Surgical Institute (as it eventually became) was ‘to provide facilities for members of the medical and veterinary schools of the University of Glasgow to enable them to carry out research into problems in the broad field of medical sciences relating to diseases of man and animals or to investigation of fundamental factors which may be important in causing disease.’

The first Head of Department (Professor Murray Harper, Head of Department, 1963-1996) was pivotal in setting the ethos of the Institute and guiding its expansion.

Professor James McCulloch assumed the headship of the department from 1996 to 2002 and continued to develop its multidisciplinary research activities.

Over more than 50 years, the Wellcome Surgical Institute has been at the heart of major advances in many areas of medicine. Seminal advances include:

- the development in animals of methods for measuring brain blood flow in man using radioactive inert gases (Murray Harper and Bryan Jennett featured in the iconic BBC series ‘Tomorrow’s World’ in the late 1960s).

- defining the contribution of axons and oligodendrocytes to acute and chronic damage to white matter in animals and man (Professor Ian Griffith ).

- insight gained into the aetiology of hypertension, by the MRC Blood Pressure Unit at the Western Infirmary, led by Professor Tony Lever (see Cardiovascular Disease – MRC Blood Pressure Unit).

- elucidating how cerebral blood flow was regulated in health and disease (the MRC Cerebral Circulation Group led by Professors Brian Jennett and Murray Harper) with Professors Eric Mackenzie, Sven Strandgaard, William Fitch and John Vann Jones as key contributors.

- the development of the first model of focal cerebral ischaemia (stroke) in rodents, a model which has underpinned research in this area for 25 years (Professors James McCulloch, David Graham and Graham Teasdale). Elucidation of the mechanisms of ischaemic brain damage benefited from the contributions of outstanding Japanese neurosurgeons, of whom Professor Akira Tamura was the trailblazer.

- the refinement of cardiac bypass and the development of new cardiac surgical techniques by Professor David Wheatley and his colleagues (see Cardiac Surgery).

- The identification of CGRP in the trigeminal innervation of cerebral vessels and its role in cerebrovascularon of CGRP and its role in cerebrovascular regulation and migraine (Professor James McCulloch and Professor Lars Edvinsson Lund University)

With the establishment of research facilities throughout the medical school, neuroscience became the dominant research area at the Wellcome Surgical Institute.

In addition, it was one of the founding departments in the Division of Clinical Neuroscience in 2002.

The success of the Wellcome Surgical Institute was recognised by repeated expansion – always with external peer-reviewed support – and by acquisition of major competitive rewards, including

(a) the first competitive programme grant from the Wellcome Trust in 1977 (to establish high resolution brain imaging)

(b) in 1985 the largest Wellcome Trust award ever made at that time to explore mechanisms of cell death in Alzheimer’s Disease with the functional correlates in man which led to the establishment of a human brain bank (under Dr Deborah Dewar’s leadership)

(c) SPECT imaging in man of perfusion, muscarinic and NMDA receptors (under Professor David Wypers’ direction)

(d) the award in 2002 from the Scottish Executive to establish 7 Tesla magnetic resonance imaging.

This award led to the establishment of a major research group, led by Professors Mhairi Macrae and Barrie Condon, utilizing pre-clinical MRI-based technology to explore experimental stroke. This now has its clinical parallel in the UK’s first ultra-high field 7T MR imager in the Imaging Centre of Excellence, alongside neurosurgery at the Queen Elizabeth University Hospital site.

The very title of the MRC Co-operative Group established in 1999 with three major MRC project grants (Brain Damage; from mechanisms to man) encapsulates the vision of the Wellcome Surgical Institute’s founders 40 years earlier. In the first research assessment exercise in 1986, the Wellcome Surgical Institute had the rare distinction of being awarded the highest grade of ‘outstanding’. The Wellcome Surgical Institute continues to enjoy international standing in the field of brain blood flow 40 years after its establishment.

The scientific papers produced at the “Wellcome” and their extensive citation provide a rigorous measure of achievement. Perhaps more important is the generation of basic scientists exposed to clinical material in neuropathology and neurosurgery and the generation of clinicians exposed to modern neuroscience methodology that were trained at the Wellcome Surgical Institute.

In the 25 years from the late 1970s, the “Wellcome”, which never had more than three full time academic staff, produced over 50 MD and PhD degrees. With their firm foundation in translational neuroscience, the majority of these graduates progressed to professorships in the UK and abroad, and to senior positions in the pharmaceutical industry including CEOs of listed companies. As much as its hard scientific output, the lasting legacy of the Wellcome Surgical Institute is its graduates who absorbed the ethos of its founders.

Professor James McCulloch

Images provided by Professor McCulloch

20th Century