BEAUTY IN HELL: CULTURE IN THE GULAG

A Taste of SLON Literature

The Solovki literary scene developed in a unique way. At first the literary production of its prisoners was similar to other camps, however, the development of a camp theatre, the presence of significant members of the intelligentsia and the help of Eikhmans made it possible for a unique literary scene to flourish within the camp.

Nikolai Litvin, Boris Glubokovskii and Boris Shiriaev managed to 'free the Solovki muse' from ideology, followed by other poets such as Boris Evreinov and Georgii Rusakov.

When publications restarted in 1929, a new breed of poets emerged in the camp. Vladimir Kemetskii and Iurii Kazarnovskii were the two most prominent, but also Aleksandr Iaroslavskii, Aleksandr Pankratov and Boris Leitin made impressive contributions to the camp's literary scene.

The selection of texts below aims to give a glimpse of the literary output of the SLON. Thanks to recordings by Igor' Loshchilov, visitors can hear the music of these poems in Russian. English readings are provided by University of Glasgow students of Russian, William Lim and Maeve Daly.

Next

Visual Arts

Back to

SLON Literature

Boris Glubokovskii

Boris Glubokovskii was a prominent figure of the early Solovki cultural scene. Glubokovskii was talented and eclectic and would write essays, plays, songs, poems (under the pseudonym Boris Emel’ianov) and tales. His essays in particular insisted that Solovki authors should be sincere in depicting their feelings, thus refusing to write ideological texts.

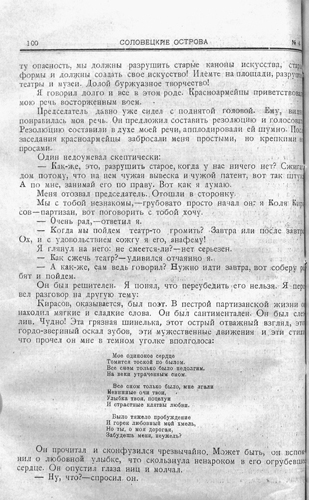

As a prose writer, Glubokovskii published the most lengthy text of the Solovki publications, Journey from Moscow to Solovki, which parodies the title of a famous text by the 18th-century Russian author Aleksandr Radishchev. Narrative rhythm and lively dialogues are distinctive features of his tale, in which the main character, Boris, progresses through a series of extremely original situations and of equally original dialogues. In this scene, set during the Revolution, the main character follows the pattern of the speeches by the representatives of Futurism and incites others to destroy theatres during a public debate, thus finding his aspirations ironically fulfilled by a member of the audience. Glubokovskii’s ironic treatment of the gullibility of the revolutionaries is crystal-clear.

Путешествие из Москвы в Соловки (отрывок)

Boris Glubokovskii - Journey from Moscow to Solovki

Меня отозвал председатель. Отошли в сторонку.

- Мы с тобой незнакомы, — грубовато просто начал он: Я Коля Кирасов — партизан, вот поговорить с тобой хочу.

- Очень рад,- ответил я.

- Когда мы пойдeм театр-то громить? Завтра или после завтра? Ох, и с удовольствием сожгу я его, анафему!

Я глянул на него: не смеeтся-ли? — нет, серьeзен.

- Как сжечь театр? - удивился отчаянно я.

- А как-же, сам ведь говорил? Нужно идти завтра, вот соберу ребят и пойдeм.

Он был решителен. Я понял, что переубедить его нельзя. Я перевeл разговор на другую тему.

Journey from Moscow to Solovki (excerpt)

Boris Glubokovskii - Journey from Moscow to Solovki (English)

I was called by the chair of the meeting. We went aside to have a word.

‘We don’t know each other’ – he started off quite rudely – ‘My name is Kolia Kirasov, I’m a partisan and I want to speak with you’

‘Nice to meet you’ – I replied.

‘When are we going to wreck the theatre? Tomorrow, or the day after? Well! That’ll be fun burning down the abomination!’

I looked at him to see whether he was joking, but no, he was deadly serious.

‘What do you mean – burn down the theatre?’ – I wondered, shocked.

‘But didn’t you say so yourself? We must go tomorrow; I’ll fetch the boys and off we’ll go’

He was resolute. I understood that there was no way he could be dissuaded. I moved the conversation onto another topic.

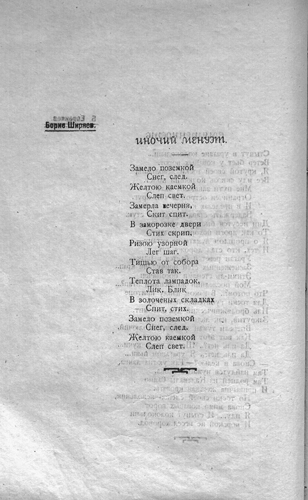

Boris Shiriaev

Boris Shiriaev was an early contributor to the Solovki publications. His texts mainly met the ideological demands of camp administration, being anti-religious and praising re-education. However, they also show symptoms of inner rebellion to the ideologically-committed texts which became more evident as the Solovki publications became freer.

The Monks’ Minuet was published between these two phases, and is a bridging text which also shows the poetical qualities of Shiriaev, who reproduced the rhythm of the minuet in the work. Despite its title appearing to be anti-religious, this is an eloquent example of non-ideological literature.

Shiriaev’s poem is ultimately ambiguous and is thought to conceal hidden meaning. Though the censors read the poem as an ironic commentary on the monks, Shiriaev managed to convey in it his anguished apprehension of the end of monastic life. This is subtly referenced by the image of the ‘dull light’ that is first used in the fourth line and on which the poem significantly ends.

Иночий менуэт

Boris Shiriaev - Monks' Minuet

Замело позeмкой

Снег, след.

Жeлтою каeмкой

Слеп свет.

Замерла вечерня,

Скит спит.

В заморозке двери

Стих скрип.

Ризою узорной

Лeг шаг.

Тишью от собора

Став так.

Теплота лампадок,

Лик. Блик.

В золочeных складках

Спит, стих.

Замело позeмкой

Снег, след.

Жeлтою каeмкой

Слеп свет.

Monks’ Minuet

Boris Shiriaev - Monks' Minuet (English)

The gale swept away

The snow, the trace.

With a yellow margin

The light becomes dull.

The vespers fell silent,

The hermitage is asleep.

In the frost of a door

A poem creaks.

Like a patterned garment

Lay the footsteps.

Through the silence of the cathedral

Becoming so.

The heat of the icon lamps,

The face of Christ.

A patch of light.

In gilded folds

Sleeps a poem.

The gale swept away

The snow, the trace.

With a yellow margin

The light becomes dull.

Vladimir Kemetskii

As a poet of the circles of Russian emigration in Paris and Berlin, Vladimir Kemetskii’s early poems are imbued with decadent depictions of the West. Once back in Soviet Russia, soon after his arrest, Kemetskii’s poetry changed dramatically. The poet appears to have started a dialogue with his muse in an increasingly sad and tormented way. Kemetskii clearly felt doomed and devoted himself fully to the depiction of his feelings in his lyric poems.

Before Navigation shows this mood. By focusing on sheer pain, Kemetskii found inspiration, channelling it into the depiction of nature – the silent godmother of his poetry. Snow-capped fields triggered the poet’s nostalgia for a world that is ‘frolicking’ elsewhere. Kemetskii's belief in his eventual freedom, which in a previous poem was ‘deceptive’, becomes in Before Navigation ‘ill-founded’, since he knew it would never be realized.

Перед навигацией

Vladimir Kemetskii - Before Navigation

В иных краях безумствует земля,

И руки девушек полны цветами,

И солнце льeтся щедрыми струями

На зеленеющие тополя…

Ещe бесплодный снег мертвит поля,

Расстаться море не спешит со льдами,

И ветер ходит резкими шагами

Вдоль ржавых стен угрюмого кремля.

Непродолжительною, но бессонной

Бледно-зелeной ночью сколько раз

Готов был слух, молчаньем истомленный,

Гудок желанный услыхать для нас

О воле приносящий весть, быть может…

Но всe молчит. Лишь чайка мглу тревожит.

Before Navigation

Vladimir Kemetskii - Before Navigation (English)

In other regions the world frolics

And the hands of the girls are full of flowers,

And the sun pours his munificent rays,

Over the greening poplar trees.

The unfruitful snow still makes the fields lifeless,

The sea is in no hurry to part from the ice,

And the wind goes with brusque strides

Along the rusty walls of the gloomy Kremlin.

In the brief, but sleepless

Pale-green night how many times

My ear, exhausted by the silence, was ready

To hear the long-awaited signal for us

Bringing news of freedom, maybe…

But all is silent. Only a seagull disturbs the darkness.

Iurii Kazarnovskii

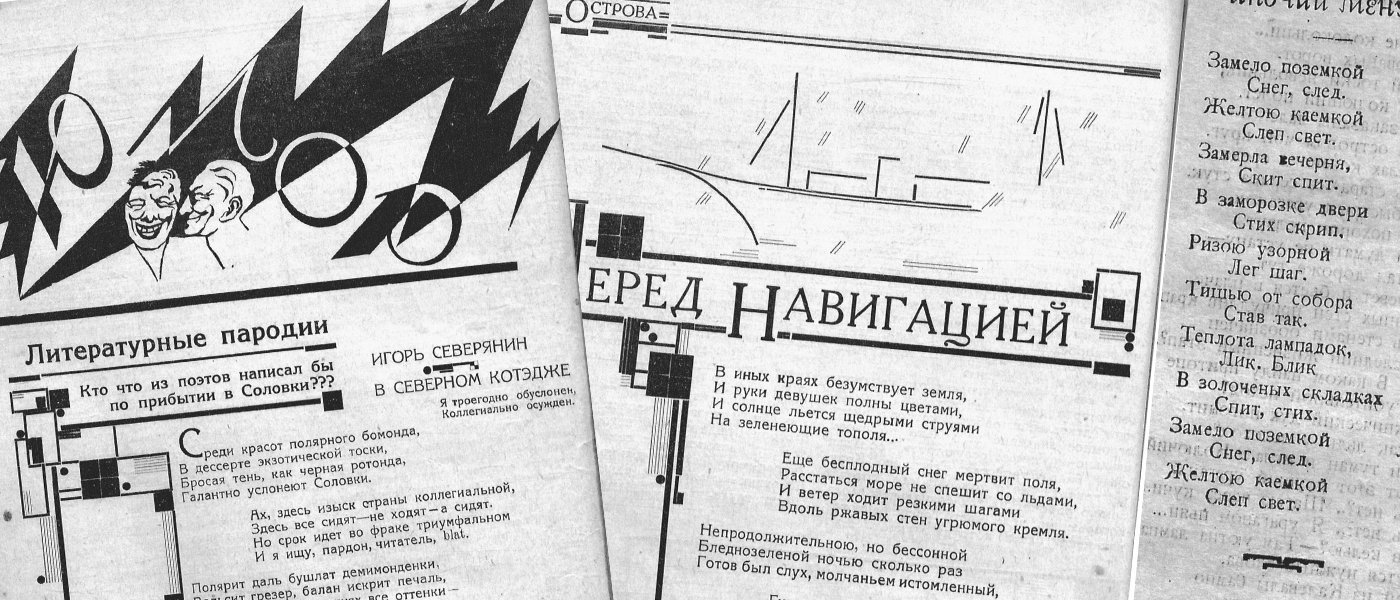

Iurii Kazarnovskii was a very gifted humourist. He published poems, short stories and humorous articles filled with wit. Kazarnovskii published a series of literary parodies of famous Russian poets entitled What would some poets write if they arrived at Solovki?, where he mimicked perfectly famous poems by Russian poets and rooted them in the reality of the camp, using the contrast between the original and camp reality in order to create puns.

There are numerous instances of puns and moments of irony in the poem below, which do not translate easily into English: the play between ‘dessert’ and ‘desert’; the reference to the rotunda connected to the elephants’ mightiness (i.e. the camp’s – ‘slon’ means ‘elephant’ in Russian); the use of the invented verbs ‘uslonet’ (i.e. they do the USLON) or ‘kaerit’ (to do the kaer, a slang word for ‘counter-revolutionary’); the reference to the nobility, which was formed in colleges and ended up in the Solovki camp; the word-play linked to the verb ‘sidet’’ which means both ‘to sit’ and ‘to serve a term’; the play on the verb ‘idti’ (to walk) in regard to the specific use of ‘srok idet’ (i.e. the term is being served); the use of Latin letters for a Russian word (which hints at criminals in the camp), while the whole text is based on erroneous spellings in Russian of French and Italian words; the reference to the balan, i.e. the slang word referred to the logs of wood harvested by the prisoners.

Литературные пародии. Игор Северянин (отрывок)

Iurii Kazarnovskii - Literary parodies

Среди красот полярного бомонда,

В десерте экзотической тоски,

Бросая тень, как чeрная ротонда,

Галантно услонеют Соловки.

Ах, здесь изыск страны коллегиальной,

Здесь все сидят – не ходят, – а сидят.

Но срок идeт во фраке триумфальном,

И я ищу, пардон, читатель, blat.

Полярит даль бушлат демимонденки,

Вальсит грезер, балан искрит печаль,

Каэрят дамы – в сплетнях все оттенки –

И пьет эстет душистый вежеталь.

Literary parodies. Igor’ Severianin (excerpt)

Iurii Kazarnovskii - Literary parodies (English)

Among the beauties of the polar beau-monde,

In the dessert of exotic anguish,

Casting a shadow, like a black rotunda

Gallantly the Solovki uslonate.

Ah, here you find the cream of the world of colleges,

Here they all sit – they don’t walk, they sit.

But the term wears a triumphant tail-coat,

And I’m looking for, begging your pardon, dear reader, a favour.

The distance of the jackets of the demi-mondaines is polar,

The gréser waltzs, the balan makes sadness sparkle

The ladies kaerate – in all shades of gossip –

And the aesthete drinks sweet a perfumed hair lotion.