Terminology

This section outlines neurodiversity terminology and language, the social model of disability, the Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA) categories of disability, and suggestions on “some things to think about”.

Important note: terminologies, policies, and practices are constantly evolving so do not worry about getting it wrong from time to time; imperfections are normal! If you are taking accountability for not knowing information surrounding neurodiversity and are actively trying to be inclusive by promoting neurodiversity, you are on the right track to providing equity and fairness to all.

Neurodiversity

The term “neurodiversity” refers to the diversity of human brains/minds, and that there is a variation of neurocognitive functioning amongst humans.

The Neurodiversity paradigm is based on the following three things:

- Neurodiversity is a part of human diversity and is valuable.

- There is no one type of “normal” or “healthy” brain, nor is there one “correct” style of neurocognitive functioning. All brains and differences in neurocognitive functioning are valid.

- When diversity is embraced, it acts as a source of creative potential.

The Neurodiversity movement is a social justice movement that seeks civil rights, respect, and full societal inclusion of neurodivergent people so that neurodivergent people are treated equally by other people, the workplace, and external environments.

Neurodivergent

The self-identifying label of “Neurodivergent” originally focused on those who are autistic. However, in recent years it has been used to describe those who think, behave, and learn differently to what is typical in society. Thus, being neurodivergent should not be considered an inherent deficit, but simply a variation in cognition.

Examples of the most known conditions that come under the label “Neurodivergent” are:

- Autism/Asperger’s/autism spectrum disorder

- Pathological demand avoidance

- Sensory processing disorder

- ADHD/ADD

- Tourette’s Syndrome

- Dyslexia

- Dyspraxia/DCD

- Dyscalculia

- Dysgraphia

- Meares-Irlen Syndrome

- Hyperlexia

- Synaesthesia

Some other conditions can also be classified as a form of neurodivergence too. These include:

- Schizophrenia

- OCD

- Anti-social personality disorder

- Borderline personality disorder

- Dissociative disorders

- Dissociative identity disorder/multiple personality disorder

- Bipolar disorder

- Mental health conditions

- Chronic neurological conditions

- Acquired brain injury

- Learning disabilities

Please note that it is common for individuals to have two or more neurodivergent labels (e.g., autism and ADHD, dyslexia and dyspraxia etc.). This is called being multiply neurodivergent.

However, there is no definitive list as it is a self-identifying label. Some people find the word neurodivergent useful to recognise the common experience and collective interests.

Thus, some people might use neurodivergent to identify themselves, whereas others might specify their condition or use terms such as learning difference; learning difficulty; learning disability; disabled person; or mental health condition (if the person has a mental health condition).

In addition, some people may use the term neurominority, neuro-atypical or neurodiverse to describe themselves. It is an individual choice.

However, we would like to note that neurodiverse refers to a group of people ranging across the spectrum of neurodiversity (for more information, please read Neurodiverse or Neurodivergent and/or What is Neurodiversity, Neurodivergent, Neurotypical).

Neurotypical & Neuronormative

“Neurotypical” is a word that aims to describe “typical” cognitive processing, whereas “neurodivergent” (or “neuroatypical”) refers to “atypical” cognitive processing.

These labels are not as clear cut as it might seem, and indeed it’s unlikely that everyone neatly fit into “neurotypical” or “neurodivergent” boxes. However, it’s useful to have language to describe cognitive processing that diverges from conceptualisations of “normal”, due to the marginalising impact of this (for more, see Botha & Frost, 2020).

“Neuronormativity” is the term that describes the idea that neurotypicality is normal (and correct), and that being neurodivergent is not. When the majority subscribe to this world view, it results in a society where there is continual pressure to appear neurotypical (for example from other people, policies, narratives, or social systems). For more information on appearing neurotypical, please see Masking / Camouflaging.

Masking / Camouflaging

Masking, also known as camouflaging, is the act of disguising one’s true authentic self by consciously evaluating your own behaviours. This can be through hiding or changing behaviours to conform to and meet socially acceptable expectations from others and society.

Originally, masking was used to explain coping strategies for autistic individuals, but it is seen across different neurodivergent conditions. Autistic masking, specifically, is where the autistic person hides or lessens behaviours associated to their autism through using different techniques/strategies to appear “neurotypical”, “normal”, or “socially competent”. Using these strategies via masking is to prevent others from seeing/knowing some of the following: the autistic person’s atypical communication styles, repetitive movements, distress from sensory information (e.g., lighting, sounds, smells etc.), that the autistic person has a highly focused level of interest(s) in specific topics, that the autistic person is perturbed by change of routine, or generally that the autistic person may have difficulties in operating/living in a neuronormative world (Neurotypical & Neuronormative). Masking is used so that the autistic person avoids exclusion from others (Hull et al., 2017; Radulski, 2022).

However, masking is also prevalent in other neurodivergent conditions. For example, research has shown that both dyslexic people and those with ADHD hide their condition or their symptoms from others (e.g., forgetfulness, talkativeness, hyperactivity for ADHD, and reading difficulties for dyslexia). Moreover, it was found that both dyslexic people and those with ADHD overcompensated in work scenarios by hiding challenges and increasing time and effort to avoid criticism and exclusion from others (McNulty, 2003; Alexander-Passe, 2015; Beaton et al., 2022; Hallberg et al., 2010).

Therefore, it is advised to keep masking in mind, but to actively try to be inclusive of differences so that neurodivergent people feel safe and accepted to be their authentic selves. For more information on this, please go to Inclusivity & Allyship.

For further information on the challenges associated to masking/camouflaging, please see Challenges Some Neurodivergent People Face, and how to harness strengths and be inclusive in Harnessing Strengths.

Social Model of Disability

The University follows the Social Model of Disability, which says that although people may be impaired by elements of their condition, they are disabled by their environment and from negative attitudes of others. For example, a flight of stairs disables a person who is in a wheelchair, not the wheelchair or disability. Further information on this can be found on Inclusion Scotland website.

Therefore, people should try and create an accessible environment to be as inclusive as possible. This may be through a proactive approach in creating, for example, accessible materials to read for all, which would be referred to as providing equality. Whereas equity would be making tailored personalised adjustments for certain people in different environments. Both equality and equity methods are advised to use in a working environment to better inclusion and acceptance of diversity. Please see the Accessibility section of this hub for further details.

Identity-first language, which means saying "disabled/neurodivergent person" instead of "person with disabilities / person with a neurodivergent condition", is aligned with the social model of disability. This highlights that a person’s condition is not a separate entity, but more so an integral part of the person.

This is particularly relevant for neurodivergent conditions, as we move away from the outdated idea that these represent something wrong with a person. Research has shown that autistic people find “person with autism” the least preferred, and “autistic person” the most preferred way of referring to themselves, although this preference is not universally shared (for a detailed discussion of this, see Botha, Hanlon, & Williams (2021).

People have different preferences about the language that is used to refer to them, and it is best to use the language that a person uses for themself.

If you are ever in doubt of what disability language to use around peers/colleagues/supervisors etc., it is advised that you privately ask what they would prefer.

For further detailed information, please read the Equality & Diversity Policy- Disability and the Equality and Diversity Unit’s Guide on Language and Disability.

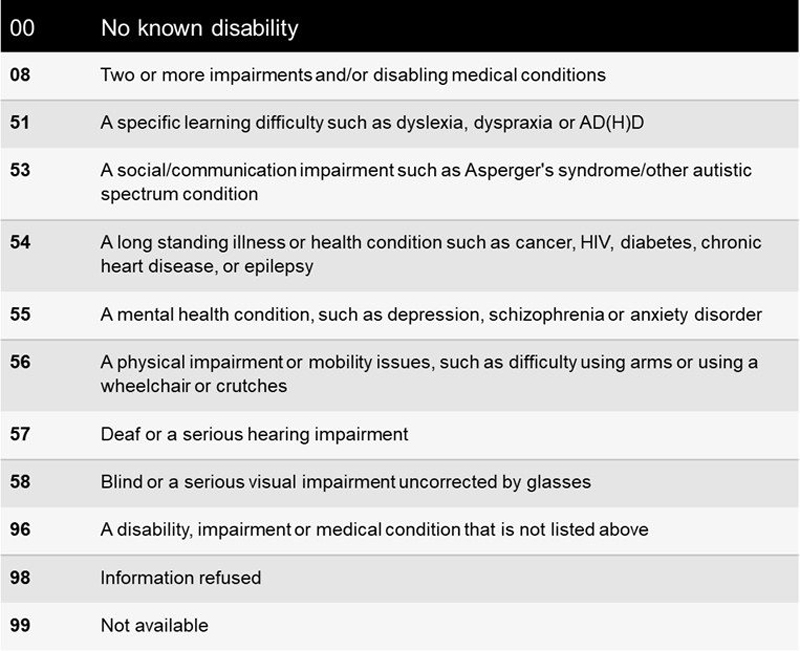

Higher Education Statistics Agency Categories of Disability

The Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA) has a range of categories that are used to collect information on disability in Higher Education. These are used by the University of Glasgow to store information of staff and students in relation to their disability condition. Please see image and description below for further details.

For example, 51: A specific learning difficulty such as dyslexia, dyspraxia, or AD(H)D, and 53: A social/communication impairment such as Asperger’s syndrome/other autistic spectrum condition, could be classified as neurodivergent conditions. In addition, 55: a mental health condition, such as depression, schizophrenia, or anxiety disorder, could also be classified as a neurodivergent condition.

If a person has more than one neurodivergent condition or has other medical conditions in addition to their neurodivergent condition (for example, autism and a mental health condition, or autism and a long-standing illness/health condition), then this would come under 08: two or more impairments and/or disabling medical conditions.

However, for other neurodivergent conditions that are not specified in this list, 96: A disability, impairment or medical condition that is not listed above, would be used.

It’s important to note that these categorisations describe disability in a way that does not align well with the Social Model of Disability. For example, it uses terms like “learning difficulty” and “social/communication impairment” to refer to ADHD and autism, respectively, which conflicts with recent research suggesting that, for example, autistic people have different, rather than impaired, communication styles (Crompton, 2020).

However, it is still useful to be aware of the HESA categories, as this is what is used by the University of Glasgow to categorise disability data.

If you fall into these categories or consider yourself neurodivergent and would like support surrounding disclosure or support, please go to Disclosure of a Condition and Support within the University.

Some things to think about

- Waiting lists for an NHS referral or assessment can be very long (sometimes up to 2 years), so many neurodivergent staff and PGR students may be waiting on their diagnosis. Therefore, if a staff member or a PGR student discloses to you that they suspect they may be neurodivergent, it is important to acknowledge that their reasonable adjustments are still valid and should be considered and met in practice; please see Disclosure of a Condition for further information.

- Due to these waiting times on a diagnosis and stigma associated to a label of a neurodivergent condition, some neurodivergent staff and PGR students may not wish to go through the process of obtaining a formal diagnosis. Thus, it is, again, important to acknowledge that a person’s reasonable adjustments are still valid and should be implemented into working practice to make the workplace equitable for that person.

- It is also important to keep in mind that the person is the expert of their own condition, therefore it is best to follow what the person labels themselves as and to avoid putting labels onto other people because they present similarly to a neurodivergent condition. The labels of the condition/s are to help people who are neurodivergent to understand their own condition(s).

- Please bear in mind that neurodivergent people exhibit their conditions in different ways based upon their upbringing, gender, race, and culture. Furthermore, a lot of neurodivergent people are taught and told to mask their neurodivergent characteristics in order to “fit into” society’s standards of neurotypical behaviour; this is called neuronormative. Therefore, intersectionality always has a hand to play, so it is good to keep an open mind for both awareness and inclusion purposes. For further information on masking, please see Masking / Camouflaging and Challenges Some Neurodivergent People Face. For further information on intersectionality, please see Importance of Intersectionality.

- When communicating with others, it is always good practice to remember that there are a multitude of communication styles, so not one communication style is the best form of communication. Please see How to Harness Strengths in Others to learn more about communication styles.