Benefactors with vision

The gifts we receive from our donors are a catalyst for change and, no matter the size of the donation, every single gift makes a difference. However, some individuals are able to make significant gifts that can drive change at the University. Looking back in our history, we celebrate the generosity and vision of a few men and women whose philanthropy transformed the University.

Collecting the world

We can all enjoy entering through the doors of one of Scotland’s many public museums to marvel at the exhibits and learn something new. But when The Hunterian opened its doors in 1807 it was the first museum in the country to be open to the general public. Renowned physician William Hunter worked at the centre of 18th-century intellectual circles and used his wealth and networks to create one of the most important natural science and cultural collections of his day.

In his will he gifted his vast collections to the University he’d attended in the 1730s and, to house them, gave £8,000 towards the cost of building a museum. Some 10,000 visitors flocked to the new museum in the Old College between 1808 and 1810. Today The Hunterian is one of the world’s leading university museums and the entire collection is recognised as an outstanding example of a Collection of National Significance, the first museum in Scotland to be awarded this status.

Image: Allan Ramsay, William Hunter, c1764–65. © The Hunterian, University of Glasgow 2017

Supporting higher education for women

Supporting higher education for women

Women’s access to university is taken for granted in the UK today but it was only in 1892 that women were admitted to Scottish universities. Isabella Elder was a leading philanthropist whose pioneering vision helped bring higher education opportunities to women.

In 1883 she bought North Park House in Glasgow for £12,000 (around £1.3m today) and donated it to accommodate the newly established Queen Margaret College, the first college in Scotland to provide higher education for women.

A medical school was established within the college in 1890 and she also generously agreed to meet its initial running costs. The college merged with the University in 1892 and, two years later, produced Scotland’s first women medical graduates. Isabella Elder’s pioneering influence can be measured in numbers. In 1892, the first year of female admission at Glasgow, 128 women, or 6%, were matriculated here and by 1908 this had risen to 695, or 26%. Today there are almost 16,000 women students at Glasgow.

Image: Isabella Elder © CSG CIC Glasgow Museums Collection

Understanding international links

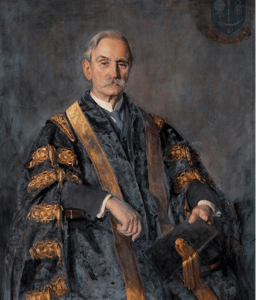

Sir Daniel Macaulay Stevenson, one of the University’s most generous benefactors and Chancellor from 1934 to 1944, supported many worthy causes and, in the aftermath of the horrors of the First World War, was particularly interested in furthering international understanding among young people.

He funded several chairs in European languages as well as a lectureship in citizenship and gave £60,000 in instalments from 1932 – worth almost £4m today – to fund exchange scholarships with European universities, with the first student, Jean H Dees, going to Germany in 1935.

Today, international mobility which broadens students’ perspectives and enhances their employability is highly valued – around 560 of our students went abroad to study in 2016. Long before our digitally connected world, Sir Daniel Macaulay Stevenson, who had travelled widely and learned several European languages himself, recognised the importance of links between the people of the world.

Image: David Shanks Ewart, Sir Daniel Macaulay Stevenson (1851–1944), 1937. © The Hunterian, University of Glasgow 2017

Leaving a legacy

Leaving a legacy

Visitors and scholars marvel at our pre-eminent collections of the work and correspondence of American artist, James McNeill Whistler.

Glasgow’s renown is thanks to Whistler’s sister-in-law and heir, as it was Rosalind Birnie Philip’s major gifts and bequest that founded the collections, which include over 800 artworks in The Hunterian, as well as thousands of letters and memorabilia housed in the Library’s Special Collections. Glasgow was chosen for several reasons, including Whistler’s Scottish ancestry, the purchase by the city in 1891 of his portrait of Thomas Carlyle and, in 1903, the decision to award Whistler an honorary degree.

Important additions have since been made but it was Rosalind Birnie Philip’s generosity that established the collections and meant that these outstanding holdings of international importance, with the world’s largest public display of his work, have been a major resource for the study of Whistler’s life and times, leading to internationally recognised exhibitions, learning, teaching and research projects.

Image: James Abbott McNeill Whistler, The Black Hat – Miss Rosalind Birnie Philip, c1900–02. © The Hunterian, University of Glasgow 2017

Building a treasure

Graduation is lent an extra vibrancy at Glasgow, with the magnificent setting of the Bute Hall providing a lavish backdrop for a day to treasure for graduates and their proud families.

But in 1877, seven years after the move from the High Street to Gilmorehill, the University’s buildings remained incomplete.

The generosity of the Third Marquess of Bute, together with Charles Randolph, enabled the completion of two great building schemes – the construction of what became known as the Bute and Randolph Halls.

The Marquess, John Patrick Crichton-Stuart, had inherited a vast family fortune that enabled him to pursue a number of scholarly, political and architectural interests. His family built and owned Cardiff docks, and he served twice as that city’s mayor.

He committed £45,000 (around £5m today) for construction and was honoured in the Bute Hall’s original decoration which was based on his family’s heraldic colours of red, blue, silver and gold.

Image: Edward Trevanyon Haynes, 3rd Marquess of Bute (1847–1900), 1883-87. © The Hunterian, University of Glasgow 2017

Gifting a grand design

Gifting a grand design

The opulent Grand Staircase – often the first glimpse of the interior of the Gilbert Scott Building for visitors – and the elegant Randolph Hall, which serves as an anteroom for the Bute Hall, are named after the marine engineer Charles Randolph.

In his will, he left £60,000 to the University (around £6.5m today) to complete the construction of the Bute and Randolph Halls, undercroft and staircase.

A student at Glasgow and at Anderson’s Institution, Charles Randolph was an apprentice before starting his own business. In 1852 John Elder, husband of philanthropist Isabella, joined his partnership, and their company Randolph, Elder & Co was one of the most successful marine engineering enterprises on the Clyde.

The arrival of his generous legacy enabled a grander treatment for the Randolph Hall than first envisaged, with the final design featuring large traceried windows, timber vaulted roof and rich decoration with walnut and mahogany panels, carved stone corbels and marble fireplaces.

Image: Sir Daniel MacNee, Charles Randolph (1809–1878), 1879. © The Hunterian, University of Glasgow 2017

Discover more about our latest campus developments:

The James McCune Smith Learning Hub

The Mazumdar-Shaw Advanced Research Centre

This article was first published in Giving to Glasgow, 2018.