Unravelling the past

A £1m Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) funded project is shedding light on Pacific barkcloth.

‘Situating Pacific Barkcloth in Time and Place’ aims to transform our understanding of Pacific barkcloth through research into the historical, cultural and material significance of three internationally important collections: those of The Hunterian, University of Glasgow and The Economic Botany Collection, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, and The National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution in the USA.

Led by the Centre for Textile Conservation & Technical Art History (CTCTAH) – home to the UK’s only Masters in Textile Conservation, and one of only a few specialist textile conservation programmes in the world - this multidisciplinary project brings together expertise from the fields of textile conservation, art history, botany and material chemistry.

Together the researchers are trying to determine what these collections can tell us about barkcloth’s design, manufacture and how best to conserve barkcloth objects for the future.

Pacific barkcloth

The University of Glasgow’s Hunterian is lucky to have one of the world’s widest and most significant collections of Pacific barkcloth, including some gathered during the first voyage of Captain Cook.

Until the nineteenth century, barkcloth was a vital material in the social, cultural and ritual lives of Pacific islanders. Sheets of the inner bark of trees were stripped and softened by soaking, then beaten with wooden mallets to stretch the cloth and to make it softer and stronger, before being decorated with painted designs.

The production and use of barkcloth was disrupted by European impact in the nineteenth century, and in some areas missionaries completely suppressed its use. At the same time, barkcloth was of great interest to travellers, and many pieces ended up in Western museums.

In 2010, Professor Adrienne Kaeppler, the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History curator for Oceania and world expert on barkcloth, visited the Hunterian and commented on the fantastic collection. A collection which no-one seemed to know much about.

Dr Andy Mills, a research associate working on the project, has been tasked with investigating the provenance of the collection. Sadly, much of what was known of the Hunterian collection's origins was lost when the museum moved from the East End of Glasgow to Gilmorehill in the 1870s.

Dr Mills has been reviewing old documentation such as an 1813 museum guide to understand what was on display back then.

To go further back, he has to look at the life of William Hunter, founder of the Hunterian. Hunter acquired a large private museum from John Fothergill, a patron of Sydney Parkinson, Sir Joseph Banks' artist on Cook’s first voyage. Parkinson produced the first European images of women making barkcloth in the Pacific. He died of dysentery on the voyage and Fothergill purchased parts of his estate (containing Tahitian barkcloth and Maori cloaks among other items) and then wrote about it in his introduction to the published edition of Parkinson’s journal.

From this written source and the fact that there are only a very limited number of ways items from the Pacific could have made their way to Britain in the 18th century, we can tell the Hunterian collection contains some of the earliest examples of barkcloth in the world.

Cross-disciplinary expertise

The sheer range of historically significant barkcloth in the Hunterian provides a unique opportunity to learn more about its design, meaning and manufacture, and how we conserve these items for the future. CTCTAH has the cross-disciplinary skills to help uncover more information about barkcloth.

Dr Mills is looking at how the design and style of barkcloth has changed over time. For example, there is a striking change of design from the 1810s onwards. Many communities changed their style of clothing or even stopped making barkcloth items due to Western influence - both from disapproval from missionaries and because exotic Western items such as wool and cloth had more value locally.

“In the early twentieth century you start to see people who are professional ethnologists or ethnographers travelling to Polynesia, and they sit down with the women and learn from them. It’s only then that people started to systematically record how many different kinds of cloths they were making, what those different kinds were, and what they were for. What do you call them? How do you produce this fabric? How do you make that pigment?"

"But by that point, you're already more than a century down the line from the missionaries turning up and saying “you should all stop making and wearing this stuff”. More than a century of Europeans importing woven cloth. So, a huge amount of stuff was already transformed before it was ever described properly. Many of the most important - religiously important, ceremonially important - types of cloth had been abandoned, because everybody had been converted to Christianity, and they had been taught to believe that many of those things were sinful relics of the pagan past.”

Dr Andy Mills

Unlike cloth or silk, it’s hard to analyse a piece of barkcloth’s source material by placing it under a microscope. The way the cloth is manufactured by beating makes that difficult. Dr Margaret Smith is investigating different scientific techniques to help establish what type of plant was used in a piece of barkcloth’s manufacture, such as DNA testing and isotope analysis. This and more importantly, the way a piece of barkcloth was manufactured (if it was soaked in saltwater or freshwater, how it was beaten out, or what it was coloured with) may have implications for the way the barkcloth deteriorates and the way we preserve these fabrics.

“For me as a Pacific art historian, working with scientists is brilliant, I'd never seen a microscopic image of these kinds of fibres before, or the way that the pigments lie on the surface of the fibres. This is very novel work in Polynesian art studies. It’s beautiful to see.”

Dr Andy Mills

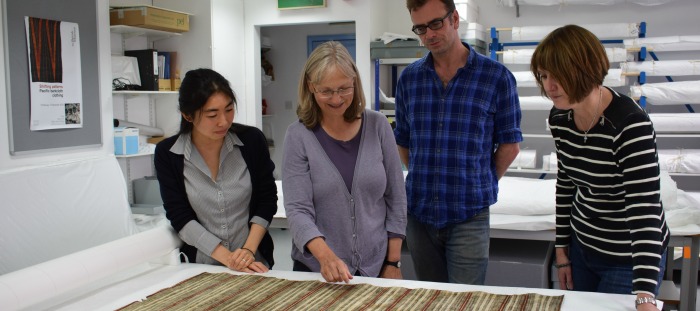

A third member of the team, Misa Tamura, is building on this knowledge to conserve the Hunterian collection, developing conservation techniques for barkcloth and preparing the pieces for display. The recent opening of Kelvin Hall allows for the space to work on these large pieces of fabric. Exhibitions of the collection, much of which has never been seen in public, are planned to be held at Glasgow, Kew and the Washington Textile Museum in 2019 after the project ends.

Global collaborations

Today, barkcloth is still produced and used in some Pacific communities, including in Fiji, Tonga and Samoa. Although some is made for tourist consumption as souvenirs, more often barkcloth is used for special occasions, such as presentations to visiting chiefs on diplomatic missions, at chiefly investiture ceremonies, and at traditional weddings for the bride and groom to sit on.

The project team are working with Pacific Islander researchers, and teams at the Smithsonian Institution and the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew, to deepen their knowledge of barkcloth.

Professor Frances Lennard, the project’s principal investigator, will host two workshops, one in Hawaii and one in Auckland. The plan is to discuss issues of interpretation, collecting, conservation and curation with people of Pacific heritage.

The project will also digitise the three collections, bringing these unique and beautiful objects to a global audience and allowing researchers and makers to search across several significant collections.

About the researchers

Professor Frances Lennard is the Principal Investigator for Situating Pacific Barkcloth in Time and Place.

Professor Frances Lennard is the Principal Investigator for Situating Pacific Barkcloth in Time and Place.

Until 2009, Frances was Senior Lecturer and Programme Leader of the MA Textile Conservation at the Textile Conservation Centre (TCC), University of Southampton. At Southampton she completed a major collaborative project on tapestry degradation, funded by the AHRC. She is currently following up this work as PI of a project on tapestry conservation and display funded by the Leverhulme Trust.

Discover more

- Professor Frances Lennard

Dr Andy Mills is a Pacific art historian, anthropologist and museum curator, and is one of three Research Associates on the AHRC-funded project Situating Pacific Barkcloth in Time and Place.

Dr Andy Mills is a Pacific art historian, anthropologist and museum curator, and is one of three Research Associates on the AHRC-funded project Situating Pacific Barkcloth in Time and Place.

Dr Mills is based in the Centre for Textile Conservation and Technical Art History, within the History of Art subject area. His main areas of research explore the reconstruction of the stylistic history of the Polynesian arts, the historical culture and colonial history of Oceania, and the history of museum collections.

Discover more

- Dr Andy Mills

Dr Margaret Smith has been a university teacher and research scientist at the Centre for Textile Conservation and Technical Art History (CTCTAH) at the University of Glasgow for the last three years. She is the research scientist on Situating Pacific Barkcloth in Time and Place.

Dr Margaret Smith has been a university teacher and research scientist at the Centre for Textile Conservation and Technical Art History (CTCTAH) at the University of Glasgow for the last three years. She is the research scientist on Situating Pacific Barkcloth in Time and Place.

Previously she was a research chemist for 22 years in both academia and industry where she gained extensive experience in analytical techniques, materials science and coordinating field trials in multidisciplinary projects.

Discover more

- Dr Margaret Smith

Misa Tamura is an objects conservator specialising in organic materials, especially those found in the contexts of ethnographic and archaeological collections.

Misa Tamura is an objects conservator specialising in organic materials, especially those found in the contexts of ethnographic and archaeological collections.

Prior to taking on the Research Conservator post for the project, she worked in institutions such as the Pitt-Rivers Museum and the British Museum, where she worked extensively with a wide range of objects from Oceanic and African collections.

Her research interests are in the conservation of barkcloth and basketry objects. She also has strong interests in the use and application of Japanese paper in object conservation.

Discover more

- Ms Misa Tamura