Worlds of Words: Dictionaries through Time

The Glasgow University Library Special Collections department is home to a remarkable collection of dictionaries of all kinds. The collection covers hundreds of years of dictionary history, beginning with mediaeval manuscript glossaries and continuing through early printed books and the Early Modern boom in English-language dictionaries up to the present day.

In this project, I used a selection of English-language dictionaries from Glasgow’s Special Collections to show how dictionaries are more than just dry reference works. Every dictionary has its own unique story to tell about the language it records and the people who wrote and spoke that language. Some are prescriptive, instructing dictionary users to employ certain words and avoid others, often in highly opinionated terms. Others are descriptive, intended to present examples of real-life language use without partiality or judgement. Many dictionaries contain a wealth of information besides the simple definition of words: detailed illustrations, etymological musings and even guides to classical mythology, among other things. The contents of every dictionary reflect a particular view of the world: a unique ‘world of words’.

There are also many fascinating details to be uncovered about the compilers and owners of dictionaries, including professional feuds and office mishaps, talented amateur linguists and dedicated teams of professional lexicographers, and characters both famous and forgotten.

In the age of Google and Wiktionary, what do dictionaries mean to us today? As well as bringing to light some hidden gems in Glasgow’s collection, I hope to explore how historical dictionaries can lead us to a new appreciation of our own relationships with language: what is ‘correct’, what do we value, and what gets written down? The making of dictionaries has been called a ‘human enterprise’1; once we recognise the humanity and history behind dictionaries, we are free to engage with them not as unchallengeable authorities but as guides and inspirations in our own personal linguistic explorations.

Rachel Fletcher, PhD candidate, English Language & Linguistics.

Rachel’s PhD research uses historical dictionaries to trace evolving approaches to the problem of linguistic periodisation: the impossibility of dividing a continuous timeline of language change into discrete periods. She is interested in how early mediaeval English has been categorised and studied by scholars over the past three and a half centuries, and specifically how dictionaries established the end-point of the period that is known today as Old English. What divides Old English from later linguistic periods, how is that division expressed, and how do we treat early mediaeval sources that are not easily categorised by this system?

Twitter: @R_A_Fletcher

Footnote:

1 Curzan, Anne. 2000. “Lexicography and Questions of Authority in the College Classroom: Students ‘Deconstructing the Dictionary’”. Dictionaries 21: 90-99.

Images:

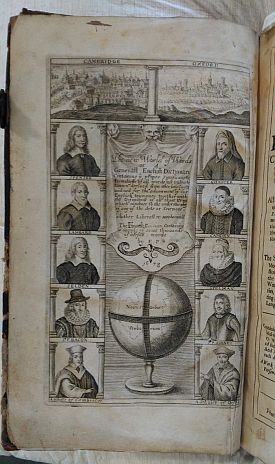

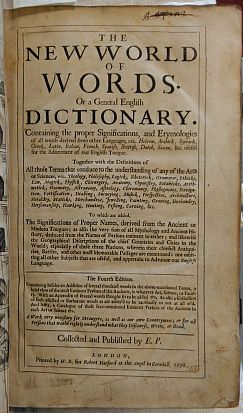

Frontispiece and title-page, Edward Phillips. 1678. The New World of Words (4th edition). Sp Coll Bk3-d.10. With the permission of University of Glasgow Archives & Special Collections.