STARN: Scots Teaching and Resource Network

The Works of John John Galt

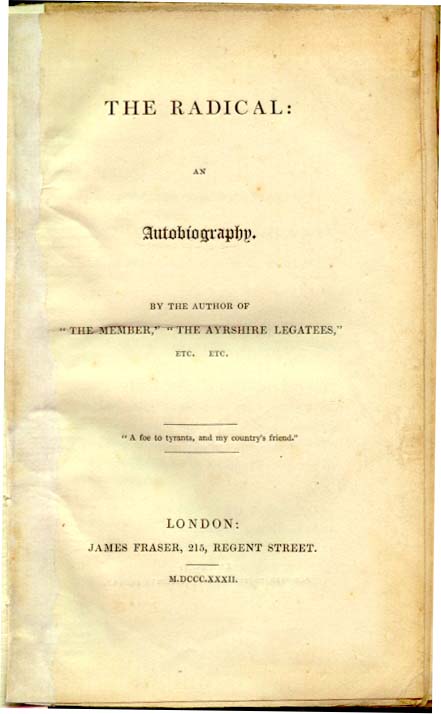

The Radical: An Autobiography

BY THE AUTHOR OF "THE MEMBER," " AYRSHIRE LEGATEES," ETC. ETC.

"A foe to tyrants, and my country's friend."

LONDON : JAMES FRASER, 215, REGENT STREET.

M.DCCC.XXXII.

LONDON:

J. MOYES, CASTLE STREET, LEICESTER SQUARE.

TO

THE RIGHT HONOURABLE

BARON BROUGHAM AND VAUX,

LATE LORD HIGH CHANCELLOR OF ENGLAND.

To you, my Lord, " the head and front" of our party, I inscribe these sketches.

No individual has, with equal vehemence, done so much to rescue first principles from prejudice, or to release property from that obsolete stability into which it has long been the object of society to constrain its natural freedom.

To you belongs the singular glory of having had the courage to state, even in the British Parliament, "that there are things which cannot be holden in property ; "thus asserting the supremacy of Nature over

IV

Law, and also the right of man to determine for himself the extent of his social privileges. What dogma of greater importance to liberty had been before promulgated? What opinion, more intrepidly declared, has so well deserved the applause and admiration of

NATHAN BUTT!

9th May, 1832.

CHAPTER I.

THE darkest hour is ever before the dawn. This the disappointed and the unfortunate should bear in mind, and cherish their hearts, in despondency, with the consideration, that if a man can afford to wait, he never fails in the end to obtain much of the object of his wishes. These reflections come with encouragement ; for now, thank Heaven, our long deferred hopes are about to be realised, - let no one despair when his fortunes seem most disastrous! Who, in this long-afflicted nation, could have indulged in the glorious anticipations that now brighten in our prospect? What man, who has tasted the bitter of Tory exultation, and been forced

2

to stoop to that abasement which, like iron, entered every Whig soul, when the arrogant official faction, in its high and palmy state, trampled on our sacred rights? But our pearls are about to be rescued from the hooves of the tramplers. The day begins to dawn, in which all honest men, with emancipated fmmunities [sic], will, in the free natural exercise of their faculties, vindicate the perfectable greatness of the human character, and lift it above those circumstances of oppression, privation, and servitude, which it has from the beginning endured.

But enough of this ; I must repress the enthusiasm with which my feelings are excited by that which is at this moment the theme of all tongues, all heads, and all hearts. I allude not to the Cholera, but to the Reform Bill. I speak not of laudanum, or rhubarb and brandy, or of any drug that has been found efficacious in the pestilence ; but of that alone which the contemptuous Tories have denominated the " Russell purge."

To return, however, to the subject of these pages - the history of my own life : - I am

3

sure that I cannot adopt any better course to secure to me the sympathy of the reader, and his participation in my joy, than by simply relating my experience during that bondage and servility from which we are all on the point of being relieved. In my sufferings I have had many companions ; and a naked recital of what we have undergone together, is sufficient to demonstrate the iniquity of that frame of society now ordained to be destroyed. Happy posterity! in vain shall ye, with all the invention of your future genius, attempt to conceive the calamities of that condition from which we, your ancestors, now intend to save you. It is reserved for you and yours to employ, with proper truth and effect, that precious expression, which the Tories of these days have so perversely used - "the wisdom of our ancestors!"

I shall not waste my reader's time with a particular account of my pedigree. Things of that sort, like other ancient errors, are fast becoming obsolete. A plain narrative of facts is all that my purpose requires ; and

4

these I shall record with a manly and undaunted pen.

My father was an attorney. In his mind the rubbish of ancient law was often inconveniently manifest : he had strange unwholesome notions of the reverence in which the decisions of tribunals should be held ; and it was his intention that I should be adulterated, in the very purity of youth, with similar respect for the same dogmas, and with the conclusions of understandings trammelled by precedents ; but Fate willed it otherwise. There was, indeed, an elastic principle of resistance within me even from my childhood ; and I have never ceased, supported by it, to regard political shackles with unabashed antipathy. My spirit was nerved with irrepressible energy against every symptom of pretension, no matter in how dear or venerable a form it menaced me.

Well do I recollect, that while yet a mere baby, playing on the hearth-rug with a kitten, which in its gambols scratched my hands, how I seized it by the throat, and how my grandmother, then sitting by,

5

took me up in the most tyrannical manner, and, before I would forego my grasp, shook me ; but it was not with impunity. The spirit of independence I have ever largely shared, and it was roused by her injustice. One of her fingers, to the day of her death, bore witness to the indignation with which my four earliest teeth avenged her intervention in behalf of the feline aggressor.

It would, however, be a tedious and vain task to recount the manifold instances in which my childhood was molested by misrule, the lot of all, under the old system. Reciprocal oppression was the very spirit of that system ; and it is no exaggeration to say, that the whole human race now in existence can verify this fact. But I allude only to the anecdote of the cat, to shew my precocious sentiment of the divine right of resistance. The circumstance, indeed, proves with what a lively discernment I was in that innocent period awakened to the sense of wrong, and the instinctive alacrity with which I resented the violence of the old woman, who, without

6

discrimination, took the adversary's part ; but she has gone to her audit, if audit there be, and I shall say no more : I have only brought it in here as my earliest recollection of my antipathy to injustice.

I might multiply domestic injuries of the same kind, of which I was the victim, especially as my mother was a person who never allowed any of her children to evince the slightest independence ; on the contrary, she often irresponsibly ruled them with a rod of iron. Perhaps, however, her discipline was inseparable from her situation, for it must be conceded, that her offspring were not always of the most pliant and submissive humour : my brothers and sisters were brats of the most wilful kind, and were ever endeavouring to make a slave of me ; but with a firmness of fortitude singular for my age, I resisted all their attempts to domineer. I shall not, therefore, animadvert with any particular rancour on the memory of "all the ills I bore" during that juvenile persecution wherein I was the martyr.

The courteous reader, after this, will not

7

object to follow me to school. On that calamitous arena it is impossible to describe what I suffered. Lenient were the lions that the Roman gladiators had to encounter in the amphitheatre, compared to the wild bipeds that I was compelled to fight with in the play-ground. O Nero and Caligula! and thou sullen Tiberius! were ye not amiable compared to the autocrats of the birchen sceptre, under whose jurisdiction I sustained the thraldom of so many grievous years? But example is better than precept ; and it belongs to the nature of this undertaking that I should describe one or two of those instances of despotism, which, in their effect, have been more durable on my mind than all the lessons I then learnt. The recollection of them, it is true, no longer excites that flush and throbbing of the spirit which I felt at their advent ; but as the boy is father to the man, I cannot entirely forget that such things were. My schoolmaster was, what every boy well knows, of course a perfect brute, and it is needless to say more about him ; universal sympathy

8

awakens at the justness of the epithet. Listen, kind reader, and I will give you a taste, by example, of that peremptory pedagogue.

9

CHAPTER II.

IT has from time immemorial been the artful aim of all education to obscure the sense of natural right. To education, therefore, I am inclined, with Mr. Owen, to ascribe all the vice and distress which deform our human condition. The antipathy, indeed, which we are taught to foster in ourselves against those ebullitions of feelings misnamed crimes, is purely conventional. The opulent and aristocratical, who have usurped the possession of property, and who by a strange fraud have wrested the privilege of legislation from the general human race, have found this essential to their interests ; and, accordingly, the indulgence of even the most ordinary feelings is branded in their vocabularies with epithets of iniquity.

I had not been a twelvemonth at school when I made this discovery ; the consequences

10

were striking ; but I must describe the story as it came to pass.

There was at that time a boy of the name of Billy Pert at our school : he was my chum and fag, and, allowing for the subordination arising from the latter circumstance, he was also my comrade and friend. It happened one day that Billy and I strolled towards the village by a foot-path we had never before frequented ; it led to the back-gate of the Rector's garden, which we approached without very well knowing the temptation into which it led.

On reaching the gate, we beheld, over the hedge that surrounded the garden, trees loaded with blushing and inviting fruit ; our mouths watered at the sight ; and Billy observed to me, that it was a shame apples should be so beautiful and not free to all who longed to taste them. The remark was philosophical ; and having heard somehow that church lands were national property, I ingeniously observed, which was to him delicious, that whatever, therefore, grew on such lands was public property : we accordingly,

11

after a little reciprocal comparison of ideas, agreed between ourselves, that we, being of the nation, could commit no moral offence in helping ourselves to those beautiful apples. With the intent to do so, but still having a dread before our eyes of the prejudices of society, we looked cautiously for an aperture in the hedge. Our search was successful ; but we observed that a window of the house stared upon the gap ; and we resolved, in consequence, to postpone the gratification of our wishes till night, when the moon, who was then in her first quarter, would assist us.

After having reconnoitered the environs, we returned to the school, and, there arranged with several other boys who slept in the same dormitory, on the mode by which we should be most likely to accomplish our desire. We went earlier than usual to bed, but we did not undress ; on the contrary, with the assistance of one of our sheets, we lowered ourselves down from the window, and with silent footsteps ran to pluck the forbidden fruit.

12

On our arrival at the breach in the hedge, we stood, however, appalled ; a candle was in the window, and the Rector behind was shaving himself, as it was Saturday night, and he deemed that task unbefitting the solemnity of the Sabbath morn. But our wits readily supplied an expedient to overcome the difficulty ; one of the boys suggesting that he and two others should go round to the front of the Rectory, and there shout and with a great noise alarm the inmates ; assured that Dr. Drowser, as the rector was called, would hasten to the scene of turbulence ; while Bill Pert with two others and I should ravage the garden.

This stratagem was speedily carried into effect : Bill and another boy scrambled through the hedge, mounted the tree, and threw us lots of apples, till we deemed that we had acquired enough; but in descending from amidst the boughs, Bill's foot slipped, and he fell to the ground, sprained his ankle, and was with the greatest difficulty hauled through the hole in the hedge, As he was excellent at whistling, it had

13

been agreed that he was to give the signal to recall the confederates from the front of the house ; but, alas, the best-concerted schemes are often frustrated ! The pain of his ankle rendered him unable to give his lips the needful expression, and I was obliged to go round and call the others off from their part in the enterprise.

It might have been supposed that in the performance of this duty no particular risk was likely to be incurred ; but Fate was inauspicious and ruined all ; for not receiving from our companions a reply to my first shout, I cried aloud, " Jem Stealth, come home!"

The Reverend Doctor was by this time looking out at one of the windows, and immediately recognising my voice, called out, with exultation, "'Tis Mr. Skelper's mischiefs." The whole party heard this, and scampered home as fast as possible, leaving poor lame Billy Pert and the apples behind them.

Billy, on finding himself deserted, bellowed as loud as possible to the Rectory,

14

and presently the whole family, with Doctor Drowser himself in his dressing- gown: and night-cap, and a candle in his hand, issued forth, and laid hold of the culprit, as they denounced that unfortunate child of nature.

I shall not bestow my tediousness on the reader with what happened that night ; but on the Monday morning -(Sabbath passed innocently) - when Mr. Skelper came into the schoolroom, there was silence, and solemnity, and dread. All those who were engaged in the assertion of genuine principle sat conning their lesson with downcast eyes and exemplary assiduity, - serious were their faces, and timid were their eyes ; my heart rattled in my breast like a die in a dice-box : the other boys were under the malignant influence that was characteristic of the then state of the world - their laughter, though stifled and sinister, was provoking ; and for the side-long looks which they now and then glanced at us, their malicious eyes ought to have been quenched.

The master advanced with sounding footsteps

15

to his desk ; his countenance was eclipsed : - never shall I forget his frown.

Having said prayers with particular emphasis, he then stepped forward, and summoned all who had been engaged in the nocturnal exploit, by name. With trembling knees we obeyed ; and I chanced to be the first whom be addressed.

"Nathan Butt," said he, with a hoarse austere voice, (for he was a corpulent man) "Nathan Butt, what have you been engaged in?"

This was a puzzler ; but I replied, "that I had just been reading my lesson."

"You varlet!" cried he ; "don't tell me of lessons : what lessons could you learn in robbing Dr. Drowser's garden?"

"I could not help it, sir," was my diffident answer ; "we were tempted, and could not resist : the Doctor should not put such temptations in our way ; he is more to blame than we are ; "and waxing bolder, I at last ventured to say, " we only tried to get our share."

Mr. Skelper was astonished, and exclaimed,

16

"What can the boy mean? You audacious rascal! these are the sentiments of a highwayman ; "and with that he hit me over the shoulders with his cane, as if he had been a public lictor, and I a malefactor. In a word, no more questions were asked, nor the truth of our opinions attempted to be ascertained ; but each and all of us were compelled, after receiving a cruel caning, to sit on a form by ourselves, ruminating indignantly on our wrongs, a spectacle to the whole school. The sequel is still more illustrative of the bold character of my companions, and the free and noble principles which from that day have continued to animate my abhorrence of coercive expedients in the management of mankind.

17

CHAPTER III.

SITUATION develops character ; and the little adventure which I have just described illustrates this truth. School-boys before, and school-boys hereafter, have been, and may be, subjected to punishment for stealing apples ; but few, I suspect, were ever animated in such an exploit by motives so exalted as mine. It was not the sordid feelings of the covetous thief that drew me into that enterprise ; but an innate perception of natural right and the consequence has been indelible : it rivetted my young determination to reform a system of society which took so little cognisance of the extent of temptation. The tale itself has often served, by its incidents, to brighten the social hour; but the effects have ever been like molten sulphur in my indignant "heart of hearts."

For days and nights after that morn of

18

retribution, I burned with resentment : my meals were unrelished ; my tasks, which were never pleasant, became odious ; one time I thought of flying from the school - of playing the Roman fool ; I roamed about the common, moody and vindictive ; and when the fit was strong upon me, I could have put the master to death ; but I was afraid of what the eloquent and energetic Caleb Williams calls " the gore- dropping fangs of the law."

From the greatest depths of despair the elastic spirit often rebounds ; and accordingly, from that ultimate abasement of purpose to which it is the nature of revenge to sink us, my spirit recoiled - I became animated with the noblest impulses : instead of subjecting Mr. Skelper to penalties, I resolved to rouse the school to a glorious Reformation. It is impossible to describe the rapture with which the conception entered into my mind. The ecstasy of Jean Jacques Rousseau, when he imagined his essay against the Arts and Sciences, was flat and stale compared with mine, which descended upon me with the

19

enthusiasm of a passion ; and I saw that the vindication of the privileges of my young companions opened a career illustrious and sublime.

No sooner had the animating idea revealed to me its beauty, than with youthful ardour I obeyed the impulse. Sagacity taught me that my companions and partners in suffering were already prepared by Destiny to listen to my suggestions with glad ears ; and it was so ; for when I took occasion to speak my purpose, they declared their willingness

"To share the triumph, and partake the gale."

It was on the Sunday week from the day of our punishment that I first broke my mind. The scene was in the churchyard, after sermon ; the bumpkin crowd had dispersed : around us were the tombs of the dead! Had we been companions of Catiline, meditating the overthrow of Rome, we could not have been more grim at first in our determinations of revenge; but as we proceeded to plan the operations, our awe of failure gradually diminished, insomuch that

20

in the end we relished in anticipation the result of the undertaking, and revelled in the assurance of success : a clear proof, as it has ever since seemed to me, that man has not that innate and gloomy abhorrence of those bold risks by which liberty must be conquered from the few who have an interest in maintaining general servitude and poverty.

Our first resolution was vengeance on Mr. Skelper ; and our next was a unanimous determination to quit the school in a body, with, three triumphant cheers, at the consummation of our success. Some of the boys, with a true republican spirit, proposed to tar-and- feather the despot ; but my humanity revolted at the idea, and I endeavoured to assuage their animosity by an exhortation to a philanthropical suggestion : others thought that he should be seized in his easy chair, and carried out of his study, at the dead of night, and plunged into a gravel- pit that was near the house and full of water. But these extremities were congenial only to the few ; and, after a long discussion, it was agreed, over a new grave, with a mutual shaking of

21

hands, that on the next Saturday night every edible and drinkable in the house should be taken away from larder, closet and cellar, by the avengers ; and that when all was fairly removed out of the house, the boys should assemble in front and give three brave farewell huzzas.

Alas! in this contrivance we counted not on the weather. The fatal night came on as wet as it could pour, and our preparations were so far advanced that discovery was inevitable ; my good genius, however, pointed out a way of rendering this disaster subservient to our gratification.

As was the case in rainy weather, we had that night the use of the school-room. There, mounted on a form, I harangued my compeers on the exigency. They received my oration with shouts of applause. I pointed out to them that it would be a confession of cowardice to be baffled by Fate, and on such a night it could not fail to be otherwise, if we attempted our original purpose ; "but," said I, dilating as I spoke, "we are in this but urged to a greater undertaking : forth

22

we cannot go in such a night ; it would drench us to the skin, and frustrate our ingenuity : let us, therefore, invoke the spirits of justice and the demon of revenge ; let us use the cords of our beds, not to hang him, but to tie the arms of the tyrant and the myrmidons of his household ; and when we have done so, let us put candles in every candlestick and empty bottle in the house, and fill his devoted mansion with illumination ; then let us place ourselves round the table, before his eyes, and riot upon every savoury article beneath his roof ; when we are satisfied, let us drink his health, and place regular watches over him for the night : in the morning, as it cannot rain always, we shall be ready to depart at an early hour."

With exultation this suggestion was adopted. A party was sent to the dormitories to uncord the beds ; and when the nightly bell was tolled as a signal for us all to go to sleep, we gave a roof- rending huzza, and each well-appointed phalanx proceeded in the execution of their several hests.

23

I led that band by which our dreadful retribution on the master was to be executed. He submitted to our cords without uttering a word ; but on one occasion he gave me a look that withered my heart. By this time the outcries of the maids were shrill and piercing, mingled with horrible giggling and screams. Old Mrs. Dawson the housekeeper, who had retired, before the bell rang, to her own chamber, hearing the uproar, came to the banisters of the stair, and inquired with alarm what was the matter ; we, however, respected her sex : she was a good-natured body, and a favourite with all the boys ; in consequence she was only ordered into her own room.

The revolution was now irresistible ; but in the midst of the fury, a cry from Mrs. Dawson's window, wild as that of fire, was heard, and presently a knocking thundered at the door. From what hand that knocking came, none stayed to question ; but all, with a simultaneous rush, fled by the back door, despite the rain, and sought refuge in the Goose and Goslings Inn at the village. The

24

arrival of so many juvenile guests terrified the landlord. The news of the insurrection spread like wildfire ; the whole town was presently afoot ; and before we could rally our scattered senses, we were led captive by beadles and constables back to our fetters.

But mark with what singular emphasis Destiny spoke her will to me : all the other boys were received back, and on the spot decimated for punishment on Monday morning, all save me ; me Mr. Skelper would not again receive : he called me the ringleader, a boy of incurable audacity, and ignominiously inflicting his toe on a tender part, bade the constable take me out of his sight.

A transaction of this kind needs no comment. I saw the full iniquity of that system in which such irresponsible power was allowed to be exercised. No prayers I said that night ; but I made a solemn vow, that the overthrow of that organisation of things in which man durst so treat his fellow-man, even though he were a child, ought to be the intrepid business of my life.

In the morning I was sent home by the

25

stage-coach, the guard of which was the

bearer of a libellous letter to my father.

What ensued on my arrival, when the old gentleman read the nefarious epistle, cannot be told ; but it gave me both black and blue reasons to resent the ruthlessness of that false position in which children and parents stand, with respect to each other. Who ever heard that, in a state of nature, where all is beneficent and beautiful, the cruel hyaena, which so well deserves the epithet, inflicts coercive manipulations on her young?

26

CHAPTER IV.

For several days after my return home, my situation might have drawn sympathy from statues. My father never spoke ; my mother looked at me in silence and shook her head : I was as a tainted thing ; and my meals, with a refinement of cruelty, were made solitary, in another room from the family parlour. The impression of such iron-hearted conduct, to a generous high- minded lad of fifteen, may be guessed, but cannot be described. My heart swelled with grudging ; and I could see no remedy for my deplorable condition, but only supplications for pardon. To this meanness, however, I strengthened myself with the sternest resolutions never to stoop ; and, in the end, my tenacity of purpose was rewarded as virtue ought always to be.

My mother, on the third or fourth day,

27

began to relent. The first symptom of the thaw was evinced by her presenting me with a pear, and saying that she hoped I had received a lesson that would serve me for life. My father, however, remained still inexorable ; and his first speech, on the morning of the fifth day, was appalling. " Nathan Butt," said he, "you have been from your infancy a turbulent child, ordained to break the heart of your parents and send their gray hairs with sorrow to the grave. The offence that you have been guilty of to Mr. Skelper can never be forgiven ; it is a blot upon your character which can never be effaced ; but you were not sent into the world to sulk in idleness all the days of your life; I have therefore resolved that you shall go to another school, where you may learn something, and redeem, by endeavour, the past. To- morrow morning you shall come with me by the stage-coach to Witherington school : you may have heard that the Rev. Dr. Gnarl, who keeps it, is a very different person from the lenient Mr. Skelper. He is a man that will make you stand

28

in awe of him; the audacity of such a thought as tying him in his chair, you will find dare not there enter your head. I say no more; but be ready when the coach passes at daylight to-morrow, to come with me."

There was something cool and steady in the severity of this speech that I did not much like, and destiny presented to me no alternative but only to submit; accordingly, in the course of the day, I began my preparations; and in the evening, much to my surprise - for I had been all these dismal days a stepson in the family - my mother invited me to sup with the rest ; and I observed that the supper on this occasion was distinguished with a spacious florentine, which I lacked not the discernment to perceive had been consecrated for the celebration of my departure; but, with the same fortitude and forbearance that have ever distinguished me in life, I resolved not to taste it, enticing and savoury-smelling as it was. In this masculine resolution I persevered, my father and mother exchanging rueful looks.

29

Without taking any part in the conversation, I retired early to bed, though not sleepy ; and as I lay tossing in the dark, I heard my mother come stepping softly into the room, and take a seat at my pillow, where she had not sat long till she began to sigh and sob. The room was dark, and I could not see ; but I have no doubt she was indulging in a fit of tears ; for she had not the spirit of a Volumnia, though her son had so much in him of Coriolanus.

When she had given way for some time to her sensibility, she inquired if I was sleeping. My innate respect for truth would not suffer me to disguise the fact, though I had an apprehension of what would follow.

On receiving my answer, she began to exhort me to change my behaviour, adding a great deal of motherly weakness and affection, more than I could endure, insomuch that, while she was speaking in the most earnest manner, I found it expedient to give a great snore, and pretend that I had fallen fast asleep. At this she rose with a heartfelt

30

sigh, and pronouncing a benediction, went away.

Early next morning I embarked with my father in the coach for Witherington, where we arrived in time for breakfast, which we took at the Black Bull Inn, and afterwards proceeded to the residence of Dr. Gnarl.

His house stood on the edge of a green common, within a white-painted railing, many palisades of which were broken, and all around wore an aspect of the ruin that is more akin to destruction than decay ; indeed, though we saw none of the doctor's pupils, it was quite evident, from the appearance of the place, that it was the domicile of numerous school- boys; and so I soon found ; for, instead of the thirty blithe and bounding boys that I had left at Mr. Skelper's, there were upwards of a hundred lads, of various ages, all of whom possessed a particular artificial character, the effect of the doctor's austere discipline, through which, however, as I afterwards observed, their natural tempers and buoyancy

31

broke out with an amiable brilliancy. They consisted chiefly of youths who had been, like me, expelled from other seminaries, but for causes of bravery which, when we became more acquainted, they were proud to relate. They were, indeed, notwithstanding their submission to the authority of the doctor, gallant and congenial companions, and had a just sense of the thraldom to which they had been consigned by their parents and guardians, in obedience to those prejudices with which society has been so long oppressed and deformed.

My introduction to Dr. Gnarl was an epochal event, never by me to be forgotten, - an era in my life. My father and I were shewn into a raw, unfrequented kind of a drawing-room, where soon after the reverend doctor came to us, and to whom my father said, at his entrance, " I have brought you Nathan Butt, my son, who I trust will, in your hands, be reclaimed from his audacious courses."

I looked at the doctor. He was a little,

32

stumpy, red-faced man, with austere eyes, and as erect as it was possible to be ; dressed in black, neatly I must say. His legs were thick, and his feet small, on which he wore bright and glittering shoes, fastened by little round silver buckles. He also wore a trim close wig, slightly powdered, with his spectacles up ; and spoke with a lisp, which inspired me at the first hearing with no reverential sentiment.

My father having some business to transact in the borough, which returned two members to Parliament, and it was then the eve of a general election, soon after left me alone with the doctor, by whom I was immediately treated in a manner that made my blood boil. Having seen my father to the porch, he bowed ; and bidding him good morning, returned into the drawing-room, where I was standing, by no means comfortable ; nor was my felicity in the slightest degree increased by the manner in which he said, -

"Nathan Butt, follow me into the schoolroom ;

33

and when the other boys have said their lessons, I shall see what progress you have made."

With these words he twirled on his heel, and marching with an air of consequence on before me, led the way to the school. I followed with a palpitating heart ; for it was impossible to conceal from myself that his accent and appearance betokened humiliation to me.

As we approached the school, which was behind the house, I heard a dreadful clamour within, which recruited my faded energies, and I took fresh heart from the music of the din ; but the moment we entered, all was silence, and my courage instantly sank, for it was a sudden and ominous tranquillity, that told, with more emphasis than words, the power with which the master ruled, and the terror with which the adolescentes obeyed.

34

CHAPTER V.

ALTHOUGH I had now turned my fifteenth year, I was not at all aware of the state of society. The blind gropings of instinct had, indeed, instructed me of something wrong in the habits and usages of mankind ; but nothing very precise could be said to have obtained my serious attention. I could see around me the hand of oppression ever visible, and I felt in my own case that power rather than justice was consulted by those who regarded my independence with jealousy. But the time was drawing nigh when the inductions of reason were to ratify the apprehensions of instinct, and the nebulae of sentiment to assume the clearness and distinct forms of rational conclusions.

I have mentioned that the ancient borough of Witherington returned two members to Parliament, and that a general election was

35

soon expected. In less than a month after my arrival at Dr. Gnarl's school, the dissolution of Parliament took place ; and at the same time it was made known that one of the old members, a Whig, retired, and that two new candidates, a Radical and a moderate Tory, intended a contest for the vacant seat. The tidings of this struggle were received with gladness by all the school; and in the course of a few days the pupils declared themselves resolute adherents of the liberal cause. Dr. Gnarl, however, with a strange sagacity, inspired by his fears, foresaw this result ; and accordingly announced that he would punish, as guilty of a gross offence, every boy who presumed to take a part in the election.

This decision was fatal to the joyful thoughts with which we were animated, especially as he declared that on the days of election the doors of the school would be shut, and no egress allowed while the poll continued open. But arbitrary absolutism has ever been defeated ; -- the boys held a consultation together in the play-

36

ground ; and it was resolved to address a round-robin to the Doctor, and remonstrate with him for so interdicting us in the exercise of our undoubted rights as Britons. Some of the bigger lads advised a different course, and suggested that we should dissimulate our principles, and pretend to be of the Tory party. This, however, was scouted by those who knew the Doctor best and longest. They asserted, that, notwithstanding all his Tory predilections within the school, he was out of it an inveterate Whig and the most pontifical of living things, maintaining that no apparent change on our part would cajole him.

This opinion soon became universal ; and the majority of the boys declaring that it would be equivalent to an abandonment of principle to disguise our feelings, the expedient of the round-robin was adopted, drawn out, and signed. It was to the following effect :-

"Sir, - Glorying in the name of Britons, we have been astonished at your prohibition of our privileges; but we will assert our

37

native and immutable rights. Give us, then, freedom to attend at the hustings, or prepare yourself to endure the consequences of a refusal."

Six boys, including me, at my own request, were appointed to present to the potentate this Spartan epistle ; and next morning, when the election was to begin, the ceremony of giving the round-robin was to be performed.

Never did an incident of the kind exhibit the corruption of nature in man more impressively than this ceremony. At eight o'clock in the morning the deputation went to present the remonstrative robin. Whether we had been betrayed by any sinister adherent, I know not ; but the Doctor was seated in his elbow-chair, and beside him stood a gigantic horse-whip. He received us, however, coolly, with a smiling countenance ; and having taken the paper in his hand, he read it aloud, carefully looking over the names. His sneers were satanic ; in the most irresponsible manner he flung the paper into the fire, and suddenly

38

grasping his whip, he laid on the shoulders of the deputation, as if they had been each an obstinate waggon-horse. We fled before him, and sought refuge elsewhere ; but his tyranny was only exasperated by our flight. One by one he called up the other boys, and treated them with as little mercy. Their cries and screams, which ascended from beneath his dreadful flagellation, for the whipping made him fiercer, filled us with sympathetic anguish and sorrow ; till one of our number, called Jack Scamp, cried out, that the cowardly rascals deserved it all, for sitting silent spectators of the outrage committed on us. This led to a change of operations. We instinctively gave three huzzas ; and with indefatigable zeal, and being on the outside of the school, broke every pane of glass in the windows. The lion at this came rushing forth, pale and ghastly, followed by the whole school, who immediately joined our party, and assisted to envelop the little man in a cloud and whirlwind of missiles, snatched from the ground. By what partial God he was borne

39

away from our vengeance, still remains undivulged ; but when the storm abated, he was no where to be seen.

Our triumph was complete. We arranged ourselves in a body on the spot, and marched in regular array to the hustings. To crown the eclat of our noble assertion of independence, we happened to fall in by the way with an old fiddler, who was playing to obtain charity. Him we instantly impressed and placed at our head, astonishing the assembled multitude at the hustings,

who made way for our procession!

I have been the more particular in these details, because they are associated with the hallowed doctrines that Mr. Chase, the popular candidate, impressed me with on that memorable day. It was, indeed, the birthday of my soul's freedom ; for the manner in which he described the malefactions of the Whigs and Tories (he spared the delinquency of neither) was congenial to my best feelings ; and the tale he unfolded of the usurpations of their aristocracies, not only in legislation, but in property, froze the very marrow in my

40

bones. It seemed to me as if the world had been, from time immemorial, in backsliding confusion; and my heart burned with a vehement ardour to arrest the chaos into which it was fatally hurrying. But in that moment, the demon of the age - that genius of the oppression which so saddens the earth - was hovering at hand ; and in the very flame and passion of my antipathy to the afflictions of the world, a numerous band of constables surrounded the whole of Dr. Gnarl's resolute youths, and, in the most shameful and lawless manner, compelled us to return with them to the school ; where the despot, with a courage that would have done honour to a better cause, welcomed us back, hoped we had been well edified by the trash we had heard, and with undaunted sobriety ordered us apart in threes and fours to our respective rooms, where he kept us on bread and water for two days ; at the end of which, to our amazement, when summoned into the schoolroom, we beheld our fathers and guardians assembled.

"Gentlemen," said the Doctor to them,

41

when we were arranged before them - "is it your pleasure to remove these rebellious youths from under my jurisdiction? or am I free to let them feel a weight of discipline equivalent to the offence they have committed?"

The courteous reader need not be told what answer the fiend of the existing order of things taught them to give ; but from that hour the law went forth ; and for the next twelve months never more than three of the boys were allowed to be seen talking or in any manner associating together, under the penalty of a severe horsing. Thus, with a harshness that would have disgraced the worst of all the Caesars, he re-established the discipline of the school ; peace was restored, - peace, did I say? Alas! can it, therefore, be wondered, that I am so animated against a system in which crimes so obnoxious to the freedom of rational beings can with impunity be committed? On that day I swore never to abate in my desire to crush a social organisation whose natural secretions evolved such suffering and guilt.

42

CHAPTER VI.

THE remainder of that year of bondage, worse than Egyptian bondage, which I breathed under the iron rule of Dr. Gnarl, completed my epoch of youth. At the end of it my father summoned me home ; and though I carried with me the reputation of being subdued, I know that in my heart I was none altered. The true complexion and the right side of things were revealed to me, and, I need not add, with no increase of admiration for either. Some of our neighbours acknowledged that they saw a change upon me ; but with that inherent predilection for detraction which belongs to morbid sentiment, they described it as something which could not be understood, and never failed to call it malignant. My stern and manly contempt of oppression, in whatsoever form it appeared, they spoke of as sullenness.

43

The effect of their calumnious insinuations was soon visible. Many lads of myown age and station, who had been originally my playmates, and whom I again expected to be the associates of my riper years, became prejudiced against me ; and the first years that I spent in my father's office after my return, for he placed me on the lofty tripod stool, were well calculated to nourish morose determinations.

I soon discovered, by that perspicacity with which I was naturally endowed, that I could only hope to be received into fellowship by the young men whom I had expected would be my friends, by a submission, on my part, of the erectness of my principles, and a pliancy of conduct towards theirs, the bare idea of which was revolting ; and accordingly, with a decision of mind, which their contumely and manifest aversion made no sacrifice, I turned from those who should have been my companions, and soon found a congenial refuge among spirits of a more generous philanthropy.

The town in which my father's house was

44

situated, had, a few years before, been a listless village ; but the accident of a wealthy manufacturer ascertaining that the brook which bounded the green was practicable for mills, induced him to build a large factory there, and doomed

"Sweet Auburn, loveliest village of the plains,"

to the hectic prosperity of the cotton trade.

Among the spinners and weavers which this insalubrious change introduced, was an aspiring band of young men, with pale faces and benevolent principles. In their society I found an agreeable sola and compensation for my abandonment of those whose station was more on a par with my own. We held frequent nocturnal meetings, at which they always treated me with the greatest respect, and made me their president ; but this honour, I felt, was, like all others, most incommodious : seldom an opportunity arose, while in the chair, to give utterance, by opinion or argument, to the inductions of my understanding ; and, in consequence, I resolved to abdicate the pre-eminence to

45

which that portion of the old leaven with which they were yet leavened inspired them to raise me. After this abdication, I found myself in all my energy ; a free gladiator in the arena, my strength and superiority were then displayed.

During the first winter we discussed general topics and the speculative conjectures of erudite men ; but when the rumours of what was then taking place at Paris reached our rural haunts, and the London mail brought daily news as it passed through our town, patriotism and curiosity constrained us to club together for a newspaper.

If the orations of Mr. Chase, on the hustings of Witherington, roused my latent feelings, that newspaper gave them tendency and purpose. It was soon evident to those brave philosophers - who were such indeed, though by profession but weavers and cottonspinners - my companions, that mankind had incurred a fearful arrear in their duties to one another ; and in vain we endeavoured to discover by what right, sanctioned by the equity of nature, lords were lordly, and the

46

poor man doomed to drudge. That something was wrong, and destructive of natural rights, in the unequal existing division of property, could not be questioned. The speeches of the illustrious great of the French Convention, confirmed by the eloquence of some of the brightest stars in the constellation of the British senate, enlightened our understandings. It required, indeed, but little other reasoning to convince us all, that the world had been led by some pernicious undiscoverable influence in the olden time to prefer the artificial maxims of society to those natural first principles which ought ever to be paramount with man.

When we had arrived, self-taught, at this conclusion, the majority of our association held resolute language, and began to nerve themselves for enterprise. A few, however, among us, tainted with a base diffidence, listened with alarm to our distinction between the institutions which originate in the frame of the social state, and those absolute rights which man has inherited from nature, anterior to the operation of

47

the gregarious sympathies that have led to the organisation of society - an organisation which gives forth the grievances of the world.

Debates for some time ran high and warm : at last we became so fervent towards our respective adversaries, that a breach was inevitable. Soon after, several of those who were considered as the champions of the existing social order, married, and became church-goers. I do not insinuate, however, by this, that they recanted their former notions of the ecclesiastical usurpations ; but I thought of what Lord Bacon says about men who give hostages to society, and ceased, in consequence, to have any intercourse with them.

48

CHAPTER VII.

WHILST I was thus, in obedience to Destiny, developing my faculties, and fitting myself to take a part in those great purposes in which I am, to all appearance, appointed to be drawn forth, it is necessary I should here relate a personal incident that has had some influence on my subsequent career, and in the adjustment of my feelings between nature and society.

About the time of which I have been speaking, an amiable young woman and I were brought into a very awkward position by the parish officers. Perhaps, as the affair was altogether private, I ought not to have mentioned it in these pages ; but as my chief object is to exhibit the perverted world as I found it, I can do no less than narrate some of the circumstances ; especially as they serve to shew how widely that artificial

49

system which has so long been predominant, is different from the beauty, the simplicity, and the integrity of nature.

For some weeks there had been a shy and diffident acquaintanceship between Alice Hardy and me, insomuch that, before we exchanged words, we had looked ourselves into familiarity with one another. She was not, however, in that rank of life which my father, in his subserviency to the prejudices of society, would approve of as a fit match for me ; and therefore I resolved to seek no closer communion with her. Nevertheless, it came to pass, I cannot well tell how, that one day we happened to fall into speaking terms ; and, from less to more, grew into a pleasant reciprocity. Nothing could be more pure and natural than our mutual regard ; it was the promptings of an affection simple, darling, and congenial.

While in this crisis of enjoyment, malignant Fortune influenced the parish, and we were undone. One morning the beadle, wearing his cocked hat, big blue coat with red capes trimmed with broad gold lace,

50

appeared at the door of Alice's mother, and calling her forth by name, impertinently inquired respecting some alteration that he had been told was visible in her appearance. To this she gave a spirited answer ; at which the intrusive old man struck the floor with his silver-headed staff in a magisterial manner, and said, with a gruff voice, which alarmed the poor girl, that if she refused to answer his question, he would have her pulled before her betters.

This threat she related to me in the evening, when we met, as our custom was, to walk in my lord's park ; and next morning I went to the saucy beadle myself, and demanded why he had presumed to molest her with his impertinence. But instead of replying as he ought to have done, he said, with a look which I shall never forget, that he was coming for me to give security that the parish should not be burthened, as he called it, with a job.

This was strange tidings ; and I was so confounded, that I did not know what answer to make. I assured him, however,

51

that it had all come of an unaccountable accident, and should be so treated ; for that neither Alice nor I had the least idea of the consequence - indeed, we never thought of it at all. But I spoke to a post ; and, by what ensued, it was plain to me how much parochial beadles are opposed to the fondest blandishments of nature.

In some respects, the affair, in the end, as far as the parish and the beadle were concerned, was amicably settled ; but my father, highly exasperated that I could not discern, or would not confess, a fault, resolved that I should no longer remain in that country side. Accordingly, I was sent off very soon to my uncle, in one of the principal manufacturing towns of the kingdom, to be placed in his counting- house ; it being deemed of no use to think I could ever make any figure in the law ; my mind, as the old man asserted, was doggedly set against the most valued institutions of the country, and altogether of an odd and strange revolutionary way of thinking.

52

"Nathan Butt," said he, on the evening previous to my departure, " you go from your father's house - what he says with sorrow and apprehension - an incorrigible young man : you have, from your youth upward, been contumacious to reproof, and in your nature opposed, as with an instinctive antipathy, to every thing that has been endeared by experience."

This address a little disconcerted me ; but in the end my independence gave me fortitude to say, - "Sir, that I have not been submissive to the opinions of the world and to yours is certain ; but it is not in my character to be other than I am. Fate has ordained me to discern the manifold forms which oppression takes in the present organisation of society - "

"Oppression!" cried the old gentleman, with vehemence, " do you call it oppression, to have been, from your childhood, the cause of no common grief to your parents ; to have been kicked out of one school, and the rebel ringleader in another? - Nathan Butt! Nathan

53

Butt! unless you change your conduct, society will soon let you know, with a pin in your nose, what it is to set her laws and establishments at defiance."

"Alas! sir, pardon me for the observation - but you have lived too long ; the world now is far ahead of the age which respected your prejudices. I am but one of the present time ; all its influences act strongly on me, and, like my contemporaries, I feel the shackles and resent the thraldom to which we have been born."

"You stiff-necked boy!" exclaimed my father, starting up in a passion ; "but I ought not to be surprised at such pestiferous jargon. And so you are one of those, I suppose, destined to be a regenerator of the world! Come, come, Mahomet Butt, as I should call you, no doubt this expulsion to your uncle's will be renowned hereafter as your Hegira. I have seen young men, it is true, in my time - that which you say is now past - who, with a due reverence for antiquity, and a hallowed respect for whatever age and use had proved beneficial - but the

54

lesson is lost on you : however, let me tell you, my young Mahomet, that we had in those days mettlesome lads, that did no worse than your pranks ; but -"

"Well then, sir, what was the difference between them and me ?"

"Just this, you graceless vagabond! - what they did, was in fun and frolic, and careless juvenility ; but you, ye reprobate! do your mischief from instinct ; and evil, the devil's motive, is, to your eyes and feelings, good! You - ye ingrained heretic to law, gospel, and morality, as I may justly say you are - have the same satisfaction in committing mischief, that those to whom I allude had, in after-life, in acts of virtue and benevolence."

It was of no use to answer a man who could express such doctrine ; so I just said to him, that I claimed no more from him than the privilege of nature. "The beasts and birds," said I, "when they have come to maturity, leave their lairs and nests, and take their places in the world."

The old man, in something like a frenzy,

55

caught me by the tuft of hair on my forehead by the one hand, and seizing a candle with the other, pored in my face, at first sternly, and then softening a little, he flung me, as it were, from him, and said, - "Go, get out of my sight, thou beast or bird of prey!"

I shall make no animadversions on such a domestic life ; the reader will clearly see that it belonged to that state of society which soon, thanks be and praise, is about to be crushed. It will no longer be in the power of one, dressed in a little brief authority, to play such fantastic tricks with those in whom the impulses of nature are justly acknowledged as superior to all artificial maxims and regulations.

56

CHAPTER VIII.

MY uncle, Mr. Thrive, was a brother of my mother, and the toppingest merchant in all the town of Slates. He was a bustling, easy-natured man, indulgent to the foibles of others, yet, at the same time, regular and respectable in his own habits. His reception of me was familiar and jocose. He had previously been prepared for my arrival by a letter from my father ; and I delivered him one from my mother, which he read over before be spoke to me ; and as he read, I could perceive a temperate smile dawn and brighten on his countenance. He, however, at the conclusion, affected a droll austerity, which was to me as relishing as pleasantry.

"You scamp," said he, "you have too good a mother ; - here is my soft sister beseeching me for all manner of kindness

57

towards you, and mitigating, with a deal of fond and motherly palaver, the impression which she fears your father, in his anger, may have produced upon me. But I will make no promises , - if you do well, it will be better for yourself ; but if you be abandoned to the follies your father speaks of, Nathan, my nephew, you are a gone Dick!"

There was certainly something in the manner of this address that I did like ; but there was also a firmness of tone in the utterance of the latter part, that fell upon my spirit with the constraint of a magic spell. I perceived that Mr. Thrive was a stout and steady man of the world ; though a merchant, he was yet less indulgent than my father, who was an attorney.

There was a great difference in their appearance too. My uncle was a portly, well-dressed person, of an urbane, gentlemanly air : my father, who had been more than five-and-thirty years the legal adviser of Lord Woodbury, one of the greatest

58

beaux of his time, was, in his appearance, the opposite of all ever deemed fashionable and favour-bespeaking. His clothes were of a strange and odd cut : he wore halfboots, light-blue stockings, and brown kerseymere inexpressibles, with large silver kneebuckles ; commonly a black satin waistcoat with spacious pockets, a bluish - grey coat with broad brass buttons, a tye-wig well powdered ; and his face was red as with the setting glow of a departed passion.

But the difference was most remarkable in their tempers. Mr. Thrive was a shrewd, sharp observer, who saw many things with a glance, which he afterwards recollected apparently without effort. My father, on the contrary, possessed but little of that alert faculty, and somehow was as little inclined to remember whatever he observed objectionable. This much I am bound to say in candour ; for it was the general opinion of those who had known him longest. Towards myself, however, I do think his character was an exception for my least faults he uniformly noticed severely, and

59

never forgot ; my most piquant remarks he often scouted with derision, or blamed with animadversion in no measured terms : in short, he was an aristocrat of the Tory tribe, and I in those days gloried in being a thorough democrat. It requires, therefore, nothing additional, to assure the reader that we did not live on the best of terms. My removal to Slates was, in consequence, really an agreeable translation ; for my uncle, what with his business, and bustling, and jocose disposition, seemed to look lightly on my peculiarities ; and for some time I spent with him the happiest halcyon days of my life ; - and yet Mr. Thrive was a stanch Government man.

When I had been a few weeks at Slates, I gradually fell into acquaintance with several spirited liberal young men, more distinguished in the town for their philosophical principles than for those aberrations in conduct, which made others of the same class less eminent for decorum. It would ill become me, indeed, to speak lightly of those to whom I allude ; but I soon was led

60

to notice that there was something of an organic difference between my companions and them.

We were of a sedate and methodical character, addicted to books more than to bottles, - thoughtful, inquisitive, and in our way of life sober and reasonable. Our adversaries, for such in truth they were, gave themselves up, in many respects, to wild and dissolute habits, possessed little information, and, with a kind of irreverent ribaldry, professed themselves the champions of those institutions of which we, on our part, considered it the greatest of duties to work the overthrow. They were, indeed, like the drunken soldier who in the Puritan war swore to a church, that he would stand by her old soul while he had a drop of blood in his veins.

It was during my intercourse with those enlightened associates, that my crude reflections on the causes of unhappiness in the world assumed form and consistency. At that time the war of the French revolution was raging ; the Great nation, having got rid of their ancient government, and having

61

cured their country of all its hereditary scrofula, was renewed in vigour ; every thing they undertook was consolatory to the oppressed of the earth ; and they exhibited to astonished Europe the amazing effects of that enlarged philanthropy which they had so long cherished, and by which they had become the foremost people in the universe. It was delightful to contemplate the triumphs of liberty among them, and how they hallowed their cause with blood. But the contrast, when I looked around me, was deplorable. Never can I forget the indignant feelings with which I regarded the obstinacy of the infatuated Pitt, and the audacity with which his sordid adherents resisted the progress of knowledge, and arrested the perfectability of man.

In the midst, however, of the humiliation which that weak and wicked statesman and his colleagues made me suffer, I was cheered, as the mariner in the storm is with the sight of a beacon shining bright and high. The disasters which so often overwhelmed their measures gave confidence to

62

my hopes that shipwreck was their doom. But it would be to weary the intelligent reader, to descant on this theme. It is sufficient to observe, that the ruling demon of society and the genius of nature were then fighting in the mid heavens ; and the latter could not but sooner or later prevail. "Thrones and sovereignties," said I, "the resources of empires, hierarchies, and orders, and the progeny of artificial life, may for a time withstand the eternal goddess ; but as sure as the moon waxes to the round bright full, she will vindicate her jurisdiction, and gladden the earth."

63

CHAPTER IX.

IT is not my intention, as I have already intimated, to record in these paces my private memoirs ; but I cannot adequately describe the impressions which I received from many circumstances, originating exclusively in that state of society which there is now the happy prospect of living to see dissolved and abrogated, without now and then departing from the strict rule prescribed to myself, and touching a little on the incidents of my domestic history.

When I had resided some time, better than a year, with my uncle, he said to me, as we were sitting together one Sunday evening by the fire-side, he looking over some family papers, and I reading Godwin's Political Justice, a work in the highest style of man

: "Nathan Butt," said he, "our family is not very numerous, and in course of nature,

64

bating my sister, you are the nearest, as the eldest of her children, to me of kin ; should you survive me, I have thought that it would be a prudent thing of you, and a great satisfaction to me, were you to make a prudent marriage. I see it is not necessary that fortune should be an essential ingredient in the choice, but it can be no detriment."

To this I replied, "That I was very sensible of the kindness with which he treated me ; but, sir," I added, "marriage is what I have never thought of : indeed, to speak plainly, I have great objections to incur an obligation, to which the world has attached so many restraints, at variance with the freedom which mankind have derived from nature."

"Pooh, pooh, Nathan," cried my uncle, "I am serious ; don't talk such stuff now ; we are not on an argument, but an important business of life."

"I assure you, sir," was my sedate answer, "I have never been more serious. Marriage, sir, is one of those artificial compacts

65

invented by priests and ecclesiastics to strengthen their moral dominion."

I shall not dispute with you, Nathan," replied my uncle, "that marriage does bring grist to the church's mill ; but we are not to judge of it merely by the tax which we pay for its blessings ; therefore say nothing on that head. Men and women must have some law to regulate them in their domicile, and as no better has yet been enacted, we must conform to what is."

"In Paris, sir," said I, "it is no longer - --"

"Nathan Butt," said my uncle, rather sternly, "I am speaking to you on a very important subject ; therefore don't trouble me with any thing about your French trash, and the utility of living in common like the beasts that perish."

I had never heard Mr. Thrive express himself in this manner before : hitherto he had only laughed, as it were, at what he called my Jacobin crotchets ; but I could discern that a feeling of a more sensitive kind affected him on this occasion. He

66

was a rich man - his favour was therefore worth cultivating ; and I frankly acknowledge that this consideration had great weight with me. But principle should be above corruption ; and I felt at the moment that I was yielding to the deleterious influences of the artificial social state, when, for a moment, I thought it might be for my interests to accede to what was evidently his intention. However, I rallied, and frankly told him that I never intended to marry.

"You are a fool," cried he, "and may live to repent it:" and abruptly gathering up his papers and rising, said, before leaving the room, "Reflect, Nathan, well on this short conversation. I do not look for an old head on young shoulders, and you are not destitute, on some occasions, of common sense ; reflect on this, I say, for a week, and next Sunday evening we shall resume the conversation."

He then went away ; and as his remarks had disturbed the philosophic equanimity with which I had been pondering over the sound and sane maxims and apothegms of

67

the book before me, I closed it ; and drawing my chair close to the fire, placed my feet on the fender, and began to ruminate on my uncle's worldly dogmas.

It was clear to me, that, with all his ability as a man of business - and in that he was considered eminent - Mr. Thrive had no right conception of the difference between man in a state of nature, and as a member of society which is in so many things opposed to nature. "What good, I would ask," said I to myself, "can he expect to reap, by alluring me, with pecuniary considerations, to hazard all that is valuable to a rational being, by taking on me the fetters of an obligation that is not only fast becoming obsolete, but is acknowledged by so many as the most vexatious that can be incurred ;" and I thought of Doctors' Commons.

For several days I did reflect on the conversation just recited, and felt, even to the Thursday night, that all my principles remonstrated, as it were, against a compliance with the wishes of my uncle ; but from

68

that evening I certainly underwent some change.

I then thought, for the first time, of the shortness of life - no elixir or expedient having been discovered by which it could be prolonged. I reflected also, with a sigh, on the uncertainty of fortune, how often the best-laid schemes were frustrated, and the seeds of' industry and skill blighted in their growth, affording no harvest. I became sad ; a feeling of grief, more intense than melancholy, occupied my heart ; and I said to myself, "Man is but a cog on a wheel, a little wheel in the great enginery of Fate."

This nothingness of individual man in the universal system of things had a great effect upon me and at last I began to think, who among all the females of our circle would make the best wife : but this was unsatisfactory. Over and over again I meditated on the subject; but the more I meditated respecting them, the faults of each became more conspicuous to me ; insomuch that by the Sunday evening, although I had resolved,

69

in submission to circumstances, to assent to an occultation of principle, I was embarrassed, and could determine on no choice. Thus it happened, when the hour came round, I was exceedingly perplexed, and, contrary to custom, instead of taking a book, as was my wont, I sat idle ; while my uncle, I could perceive, eyed me with occasional sinister glances, that made me thrill, as if I felt that he suspected me of some delinquency. At last he broke silence :

"Well, Nathan Butt," said he, "I observe by your manner that you have been giving some heed to what I said last Sunday night ; what is your determination?"

"Truly, sir," was my diffident answer, "I know not what to say : marriage itself I consider as one of the incidental evils of the social state, and until that undergoes a thorough reformation, it appears to me, all things considered, that, out of a philosophical respect for the opinions of others, it must be tolerated."

"Well, Nathan, I do not say that your remark, which looks so like philosophy, is

70

altogether nonsense ; but the matter in hand is, Are you, then, disposed to take a wife?"

"I cannot exactly answer that question, because I am acquainted with no young lady that I would prefer more than another ; and therefore, as I have little inclination for the state, and no motive of preference, I am very likely to remain a bachelor."

"Well, I must say, Nathan, you are a young man of very odd notions ; but as I am convinced marriage is the best, thing that can happen to you, my endeavour shall not be wanting to discover a proper match. What think you of Miss Shuttle, the daughter of my old friend ? I have long considered that she would make you a very suitable wife, being largely endowed with good

common sense, with which you are not overburdened, and a cheerful social temper, in which you are greatly deficient."

Now, Miss Shuttle had never blithened my cogitations ; but the moment my uncle mentioned her name, I was sensible of an attractive bias towards her. Not, however, to trouble the courteous reader with further

71

particulars, let it suffice that we were in due time made man and wife, according to the most approved forms of the Establishment ; though I, being the son of a Dissenter (for my father was a Presbyterian), would have preferred a ceremony less ostentatious.

72

CHAPTER X.

MY wife certainly possessed those qualities for which she had been recommended ; her only fault was, indeed, of the most blameless description. She had not the slightest predilection for ratiocination ; but, on the contrary, she was a living effigy of passive obedience ; and it was only in this supple compliance that I ever found her tiresome. Once, however, she did evince a capability of sustaining an argument - the highest faculty in man ; and I have never since ceased to wonder at it, for on that occasion she was triumphant.

She had changed our cook ; at which, as the woman was civil and managing, I expressed some surprise, it being my habit to partake of my philosophical share of dinner without remark.

"What you say, my dear, is very true,"

73

was her answer ; "she is an excellent creature, but a very bad cook, and I hired her for a cook."

"But," replied I, "you should have balanced her good qualities against her defects."

"That would not have mended her cookery - it would still have been as bad as ever ; and you cannot deny, Nathan Butt, that good eating is one of the greatest comforts in life."

"Is it ? I'm sure, Mrs. Butt, I pay no attention to it : it is a subject - an animal subject - beneath the dignity of an intellectual being."

"It may, sir ; but when one thing at table happens to be better than another, I observe you instinctively prefer the best ; and it is only by having a good cook that we can be sure of enjoying a comfortable life."

This silenced me ; it being evident that the enjoyment we have in eating, especially in good eating, is one of the few unimpaired innate immunities of the species ; and that

74

my wife was quite right in her estimate of a cook.

With the single exception of this brief discussion, we never had a word which shewed the least difference of opinion between us : indeed, I had no occasion to contradict her ; she always submitted to my pleasure, and so maintained, in an amiable manner, the peace of our house.

Although the accordance of my conduct to the promptings of nature, was generally, I may truly say always, reciprocated by Mrs. Butt, we yet had one serious controversy ; all others were uniformly of the most amicable kind. It only required a little firmness on my part to see that every thing was done as I desired ; for I never could abide to debate first principles in such trifles as household particularities. I anticipated all objections by the judicious serenity with which I announced my will and orders. But uniform tranquillity belongs not to man in his social condition.

In the course of the second year after our marriage, my first-born in wedlock, a son,

75

came to light. At that epoch there was a moderation in men's minds, such as had not been experienced for some years. The French, under the fatal dominion, of Napoleon, had lost much of their interesting character. He had degraded himself by a union with the sentenced blood of Austria ; and those who had once thought they saw in him the deliverer of the human race ; were mortified by his apostacy. The effect of this made me, as well as all of my way of thinking, shrink back into ourselves, and seek to obscure our particular opinions by a practical adherence to the existing customs of the world - errors and prejudices which we never forgot they were.

It thus happened, when Mrs. Butt proposed to me that our child should be baptized, I made no objection ; only remarking, that it was a usage to which we must submit, and the expense being inconsiderable, it was not a case in which we should shew ourselves different from our neighbours.

Sometimes before, I had observed that she was not very well satisfied with an occasional

76

word which dropped from me respecting priestcraft and ecclesiastical usurpation ; but as my father was a Presbyterian, she ascribed those accidental strictures to the tenets of his sect, supposing me of the same persuasion. But that I should speak of baptism as deserving of consideration only on account of the fees, produced an effect for which I was not prepared.

She was standing when she put the question, and I was reading the book of a recent continental traveller, a man of liberal principles, who had shrewdly inspected the world, and correctly discerned its prevalent errors and abuses ; for it was, indeed, chiefly from such travellers that I obtained right expositions of these controverted topics. Without raising my eyes over the edge of the leaves, I gave her the answer quoted ; to which she made no reply, but, retreating backwards to the elbow-chair opposite, sat down and drew a deep sigh.

Not expecting that any thing particular was about to take place, I took no other notice of her consternation than by casting

77

a glance over the top of the book ; which she observed, and, wiping her eyes, suddenly rose and went away, and wrote to my mother on the subject. In the course of two or three days, on the evening before the day appointed for the christening, the old lady made her appearance ; having come, as she unhesitatingly declared, to witness the solemnity.

I welcomed her as she justly merited to be from me ; for although in some things she was wilful, as most parents are, she nevertheless had made herself, by her kindnesses, a cosy corner in my bosom, and I was sincerely glad to see her, - a little surprised, however, at her unexpected visit.

Early next morning my father also arrived by the mail. He had travelled all night, and seemed in rather an irksome humour. After swallowing a hasty breakfast, he went directly to my uncle ; saying, in a manner that struck me as emphatical, that they would both dine with us, adding, "The ceremony must be deferred till the evening;" and, grinning with vehemence,

78

he shook his stick at me as he left the room, adding, " You blasphemer, to break my heart in this manner!"

The secret motive of the visit was thus immediately disclosed ; for no sooner was his back turned, than my mother and Mrs. Butt took out their handkerchief - as evidently preparatory to a scene, as the drawing up of the curtain is to a tragedy.

"Much has your poor wife, Nathan Butt, endured ; but this is beyond pardon. I have come a long journey, and your worthy father has travelled all night - a dreadful thing at his age. We can, however, forgive all that ; but who will forgive you for making the baptism of your first-born a consideration of parish fees, with no more reverence for religion than if you were a sucking turkey?"

"Do turkeys suck?" said I : "that they are irreligious is doubtful. I have often myself noticed that they, as well as other poultry, never take even a drink of water from the dub, without lifting their heads and eyes towards the heavens in thankfulness."

"Oh, Nathan, Nathan!" was her exclamation,

79

in an accent of grief that smote my very heart, "what will become of you and your poor baby? for now ye're the head of a family. Oh, oh!"

I made no answer ; but I could not help wondering at the folly of the general world in thinking religion something different from the forms and genuflexions in which its offices are performed ; or that there was aught in it beyond the ingenuity of those who in different ages had invented its several rites, as a mode of levying taxes for the maintenance of their order. And I turned to my wife, who was sitting hard by, and, with really more asperity than I ever made use of to her before, said, "What is the meaning of this ? Surely you very well knew that I was quite neutral in my wishes on the subject. If you desired our boy to be made a Christian, I had no objection : by making him undergo the ceremony, he could not therefore be less a man. You might have spared me from the reproaches of my father and mother, whose prejudices, at their time of life, it is vain to assail, and

80

allowed the infant to be baptized quietly, and without more ado."

Her reply filled me with amazement : "In all temporal things, Nathan Butt, I considered it a duty - a sworn duty - to obey you, and never till this occasion have I ever felt a wish to depart from the strictness of my marriage vow. But, Nathan, this is not an earthly and mortal matter ; the soul may be in danger of hell- fire by us ; and religion admonishes me, yea strengthens me, poor, weak, and silly thing that I am, to give this sentenced scion of a fallen race the chance of salvation."

I was confounded by her energy, and I pricked up my ears, for her manner was full of a fine enthusiasm, and she spoke like the Pythia. My mother then took up the strain, but with more familiar rhythm.

"She entreated your father and me," said the old lady, " to come to her aid ; for she could not in conscience allow you, in your present state of unbelief, to take upon you the baptismal vows. Your father and uncle are to be the sponsors."

81

"And am not I to have any thing to say in this affair?" replied I, a little fervently; for it seemed to me then, as it has done ever since, something beyond all toleration, that a father should, by any occult influence of the theocracy, be thus deprived of his natural right.

"Do you deserve to have any?" cried my mother.

My answer was sedate : "I do not reckon on what I may deserve, but only on what is due to me as a parent."

"This, Nathan," said my wife, "is not what is due to a parent. God has revealed that by baptism the condemned souls of the tainted race of Adam will again be rendered acceptable to his love ; but wherefore it has been made the qualification for that election is a mystery. Yes, Nathan, I may in this be a disobedient wife, but there is holiness in the disobedience ; and I hope that our dear baby, by receiving the sign and impress required by the Redeemer, will become eligible to partake of the blessing."

82

"Why should there be mysteries in the world?" said I.

"Why should you be in the World?" exclaimed my mother.