Runaway slaves: uncovering slavery in Britain

A database of 18th century newspaper advertisements for the recapture and return of runaway slaves in Britain created by University of Glasgow researchers has had a global impact on our understanding of slavery in Britain at that time.

The Runaway Slaves in Britain project has inspired educational resources, films, plays and a graphic novel. The research has also contributed to the University of Glasgow’s programme of reparative justice to address today’s injustices caused by the legacy of slavery.

Funding and method

For three years, a team of researchers from the University of Glasgow have painstakingly located, transcribed and entered into the database newspaper notices for enslaved and bound people who escaped in Britain, as well as notices advertising the sale of enslaved people.

The research team – Stephen Mullen, Nelson Mundell and Roslyn Chapman - worked through archives of Scottish and English newspapers published between 1700 and 1780 (many of which could not be digitally searched) held in Edinburgh, Glasgow, Liverpool, Bristol, Cambridge and London.

More than 800 of these 18th century newspaper adverts were placed by masters and owners offering rewards to anyone who captured and returned the runaways and, often, threatening legal action against anyone who harboured or helped them. These records represent a larger group who also escaped but were not the subject of adverts, and a much larger group still who never escaped. The adverts give us a fascinating and disturbing insight into lives of the men, women and children who tried to flee their servitude, providing a rich source of information about slavery and the enslaved in Britain.

In many cases, these brief adverts are the only surviving documentary record of the person’s existence as Professor Newman explains: “We hardly ever know anything other than what is included in the advertisement itself. A successful escape meant disappearing from the record, and an unsuccessful one did not generate any other documentary record. The rare exceptions are when there are law cases over whether or not a person who escaped should be returned to their master, and we really have only one of these.

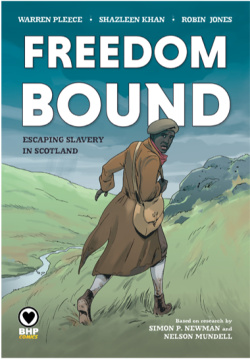

“This is one of the reasons we have worked extensively with people in the creative arts: playwrights, film-makers and a graphic novelist, using our research - not just in these advertisements, but into people of colour in 18th century Britain more generally - to create stories about what might have happened to these people.”

The Runaway Slaves in Britain database – which is freely available for use by academics, students and interested members of the public from all over the world - is now the largest collection of evidence of enslaved and bound people in 18th century Britain. It demonstrates that racial slavery was not just a distant, far removed, colonial reality but that many enslaved and bound people lived and worked throughout Britain.

Discover More

- Project website: Runaway Slaves in Britain

- Database of Runaway Slaves

- Funder: Leverhulme Trust

Wider impact

Since launching in June 2018, there has been worldwide interest in the Runaway Slaves in Britain research project and database. In its first year alone, the dedicated website was visited 277,000 times by people from 85 countries, generating 3.97 million page views.

There has been worldwide interest in the Runaway Slaves in Britain research project and database. The website has been visited 277,000 times by people from 85 countries.

The database has garnered extensive media coverage not only in the UK – including BBC Radio Scotland, The Herald, The Daily Mail and STV News – but also globally in The New York Times and the Washington Post. Social media publicising the database has been widely shared including a re-tweet by influential American civil rights activist, Reverend Jesse Jackson Sr.

With an ambitious public engagement strategy – collaborating on radio documentaries, theatre, film and music productions - the research is reaching a broad audience. Over 12,000 copies of the graphic novel, Freedom Bound – which tells the story of three runaway enslaved people in Scotland - have been distributed, along with teaching resources, to all Scotland’s state secondary schools.

Find out more: Freedom Bound Graphic Novel

Reparative justice

The project inspired the University of Glasgow to gain a deeper understanding of its links to slavery and undertake a programme of reparative justice. The report - Slavery, Abolition and the University of Glasgow - the first report of its kind in the UK, outlined the University's historical links with racial slavery and recommended a programme of reparative justice. As a result Glasgow became the first in the UK to join Universities Studying Slavery.

Professor Newman said: “The University of Glasgow uses financial gifts, endowments and bequests for good educational purposes. James McCune Smith, for example - a former slave and the first African American to receive a medical degree - was supported in his studies at Glasgow.

“However, our report acknowledges that in the 18th and 19th Century the university received some money from people who made part of their money from slavery, or more usually, from the trade in goods produced by slaves. That’s why it is appropriate to seek a form of reparative justice in which the university can help redress some of present day disadvantages caused by the institution of slavery.”

The future

To date the team have supported five other UK Universities to take similar actions.

As part of the reparative justice agreement a joint research centre, the Glasgow-Caribbean Centre for Development Research, has been established with the University of the West Indies. The Centre will help to stimulate public awareness about the history of slavery and its impact around the world.

Enslaved people in 18th Century Britain endured many forms of inhumane degradations but the Runaway Slaves in Britain project ensures that their existence and suffering cannot be erased or forgotten from our collective consciousness. Reparative justice can offer practical and innovative means of redress in the 21st Century.

Discover more

- Read the report: Slavery, Abolition and the University of Glasgow

- Universities Studying Slavery

- Slavery Studies at Glasgow

- Other slavery related research projects at Glasgow

About

The Runaway Slaves in Britain project, led by Professor Simon Newman, began in 2015 with £219k funding from the Leverhulme Trust and support from the School of Humanities and the College of Arts & Humanities at the University of Glasgow.

Award-winning

In 2019 project won Research Project of the Year at the Herald Higher Education Awards, and Best Community or Public Engagement Initiative at the University's Knowledge Exchange & Public Engagement Awards.