Guest Blog: Common Misgivings About Scottish and Irish Food Cultures

Published: 1 August 2022

I’ve encountered claims that Scottish (and Irish) food is plain and simple at best, and unimaginative at worst. However, a cursory search for oats in both Scottish and Irish food literature reveals a multitude of applications and preparations—breads and cakes, fermented liquids, and pottages to name but a few—suggesting the creative manipulation of a staple crop rather than unimaginative resignation to monotony.

In both academic writing and in popular culture, I’ve encountered claims that Scottish food is plain and simple at best, and unimaginative at worst. After reading Grith Lerche’s “Notes on Different Types of ‘Bread; in Northern Scotland: Bannocks, Oatcakes, Scones, and Pancakes” (following my doctoral supervisor’s advice that I cast my net wide to shape my thinking about women’s work, domestic space, empire, food history, and cultural heritage in early twentieth century Ireland), I knew that this diagnosis of Scottish (and Irish) cooking—plain, simple, and unimaginative—required further investigation.

In both academic writing and in popular culture, I’ve encountered claims that Scottish food is plain and simple at best, and unimaginative at worst. After reading Grith Lerche’s “Notes on Different Types of ‘Bread; in Northern Scotland: Bannocks, Oatcakes, Scones, and Pancakes” (following my doctoral supervisor’s advice that I cast my net wide to shape my thinking about women’s work, domestic space, empire, food history, and cultural heritage in early twentieth century Ireland), I knew that this diagnosis of Scottish (and Irish) cooking—plain, simple, and unimaginative—required further investigation.

Based on an ethnographic study in Northern Scotland, Lerche shares the following recipe for Mrs. Calder’s oatcakes:

“2 handfuls of oatmeal (4 oz.)

1 teaspoon of melted dripping

1 teaspoon of salt

pinch of baking soda (i.e. bicarbonate of soda)

enough water to make a stiff paste”

From these brief instructions, many challenges to limited views of plain and simple food in Scotland emerge. A first line of investigation lies in the humble word “handfuls.” On the surface, this seems like an imprecise and rudimentary form of measurement made clearer through the addition of “4 oz.”, but it deserves more nuanced consideration. A “handful” (of the star ingredient here) communicates tactility and discernment; foodstuffs measured by and in the hand are subject to a form of evaluation (e.g., texture, density, quality) that standardisation obscures. “A handful” as an instruction in a recipe also implies expertise and experience; no two handfuls are alike, which suggests the real-time adaptive capacity of cooks like Mrs. Calder. “Enough” water and “a pinch” of baking soda in the last lines achieve the same: the baker must decide.

Despite owning a new cooker, Mrs. Calder insisted on baking her oatcakes (and scones and pancakes) with a griddle over a peat fire. This underpins the sense of multiple temporalities at play in the kitchen, rather than successive, linear periods of modernity and “progress.” I have no doubt that Mrs. Calder could have made exceptional oatcakes using her electric stove; what is more important here is her expertise in determining how to transform simple and plain ingredients in the best way. Finally, even a cursory search for oats in both Scottish and Irish food literature reveals a multitude of applications and preparations—breads and cakes, fermented liquids, and pottages to name but a few—suggesting the creative manipulation of a staple crop rather than unimaginative resignation to monotony.

Despite owning a new cooker, Mrs. Calder insisted on baking her oatcakes (and scones and pancakes) with a griddle over a peat fire. This underpins the sense of multiple temporalities at play in the kitchen, rather than successive, linear periods of modernity and “progress.” I have no doubt that Mrs. Calder could have made exceptional oatcakes using her electric stove; what is more important here is her expertise in determining how to transform simple and plain ingredients in the best way. Finally, even a cursory search for oats in both Scottish and Irish food literature reveals a multitude of applications and preparations—breads and cakes, fermented liquids, and pottages to name but a few—suggesting the creative manipulation of a staple crop rather than unimaginative resignation to monotony.

And yet, from both the Irish and the Scottish perspective, scholars need to remain vigilant that we do not descend into nostalgic views of the past that might romanticise conditions of poverty and situations of lack. We need to stay attuned to how class, perhaps more than location, is sometimes a better way to access food history. There are other ways that we need to stay sharp, too, as Scottish and Irish food studies grow and flourish. For example, how did empire at once propel an underappreciation of Scottish foodways through the colonial gaze while also forging new eating habits and benefitting Scottish agents of empire at the expense of those colonised further afield? The pineapple—extracted, grown in hothouses, and symbolic of wealth and status in both Scottish (and Irish privileged) circles—comes to mind here. Moreover, what contributions have immigrants made to food in both Ireland and Scotland?

Coming from the perspective of food scholarship in Ireland, a country also very much misunderstood with respect to food culture, I see innumerable ways to question, problematise, contextualise, and appreciate “plain and simple” culinary traditions and cooking in Scotland.

Warm thanks to Laoighseach Ní Choistealbha for her editorial feedback and with gratitude to National Folklore Collection of Ireland for its generous image reproduction policy.

---

Image 1:

“The Photographic Collection, C015.01.00002” by Dúchas © National Folklore Collection, UCD is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0.

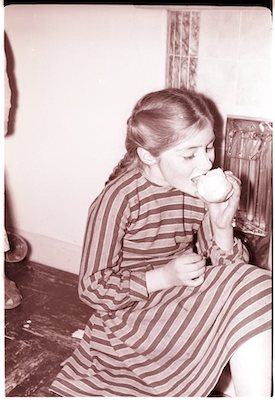

Image 2:

“The Photographic Collection, N013.06.00044” by Dúchas © National Folklore Collection, UCD is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0.

Meet the author:

Gabrielle Kathleen Machnik-Kekesi (she/her) is a Hardiman Research Scholar (2021-2025) at National University of Ireland, Galway, working under the supervision of Dr Nessa Cronin. She holds an Individualized Program master’s degree from Concordia University, Montreal (Gender Studies and Modern Irish History) and a master’s in Information Studies from McGill University, Montreal (Archival Studies focus). Her research intersects topics and fields including Irish studies, food studies, empire, critical cultural heritage, women’s history, and domestic space.

First published: 1 August 2022

<< Food Blog