Vascular Surgery

Apart from two isolated but remarkable operations by Hogarth Pringle in 1912 the local history of vascular surgery really began in the 1950s1.

In fact Glasgow was at the forefront of worldwide developments in this new field. At that time, arterial surgery was not generally attempted and there was therefore little treatment for patients with gangrene, aortic aneurysm or carotid artery disease. Experimental replacement of diseased arteries with freeze-dried homografts from cadavers was occasionally attempted, but with variable results.

Vascular Surgery "Firsts"

A patient was admitted to Glasgow Royal Infirmary for such a freeze dried aortic homograft in the early 1950s. However, the Procurator Fiscal in Glasgow was not keen on the notion of recovering arteries from “healthy cadavers” at the mortuary. These days were many years before the current familiarity of organ transplantation.

Mr William Reid, consultant surgeon at Glasgow Royal Infirmary, who was developing an interest in vascular surgery, travelled to London and visited the best tailor in town. He bought two shirts and asked his theatre sister Jane Anne McKenzie to take them to her digs and cut the tails off the shirts. She fashioned the two tails into two tube grafts using her landlady’s sewing machine. Her husband Bill Lang happened to be the resident in the unit, and he used his own blood to test one in order to make sure that it would not bleed through the fabric. The home-made artificial tube graft was sterilised overnight and implanted into the patient the following day.

This was the very first prosthetic vascular graft implantation in the United Kingdom.

One of the authors performed a carotid endarterectomy many years later on the patient’s son.

She fashioned the two tails (from two shirts from the best tailor in London) into two tube grafts using her landlady’s sewing machine

With this spirit of adventure in surgery, William Reid and Kennedy Watt formed the very first pure vascular surgery unit in the United Kingdom in 1957, with the approval of the Glasgow Royal Infirmary Board.

This meant that they dedicated their time to giving people a chance of life, restoring function and viability to critically ischaemic limbs, and also selecting patients for carotid artery surgery to try to prevent strokes.

They invited the Health Minister to show him what they were doing and introduced the Minister to patients and staff, as well as showing him their publications. The minister wrote a cheque for £100,000 the same day, and ward 20 at Belvidere Hospital was opened, in addition to the unit working in the 5th floor surgical unit in the Royal Infirmary, using the same theatre that Hogarth Pringle had used.

In the days before reconstructive vascular surgery, operative lumbar sympathectomy sometimes saved a limb from amputation. In Edinburgh, Professor James Learmonth was knighted for performing an operative sympathectomy in 1949 on the King, George VI, who had gangrene of his foot. However, open operative sympathectomy on elderly patients carried significant risks. Mr Reid asked the hospital pharmacy to make up an aqueous solution of phenol, one part in fifteen, and injected this into the lumbar sympathetic chain instead of removing the chain at open surgery. It worked. This minimally invasive advance led to many thousands of patients benefiting locally without the need for open surgery.

A notable surgeon who collaborated strongly with the Royal Infirmary unit was Tom Gray, a surgeon at Stonehouse Hospital. In 1970, Reid, Watt and Gray published the description, technique and results of over 1000 chemical sympathectomies2.

Interestingly, when Mr Reid also tried chemical cervical sympathectomy of the stellate ganglion in patients who presented with an acute stroke, he frequently noticed immediate improvement in their neurological function. This was long before the constraints of governance. Doctors tried new things freely if they felt it might help the patient.

The Woman with the Golden Arm

In the early 1960’s a woman presented at the Royal Infirmary with an ischaemic left arm that was cadaverously white. This was before embolectomy catheters, and the results of “washing out” the artery from above and below the clot were poor. Mr Reid exposed the brachial artery and inserted a fine catheter to instil a new fibrinolytic drug called streptokinase. Over the weekend he serially advanced the catheter, taking angiograms as the streptokinase dissolved the blood clot. He advanced the catheter into the palmar arch. The woman had a wonderful result – her arm was completely saved. Streptokinase was very expensive, and her husband proclaimed that she was “the woman with the golden arm”.

This was the first case of peripheral arterial thrombolysis in the world, and probably also the first endovascular case. Every author on the publication became a professor, except for Mr Reid!

An important collaboration had started between the Vascular Unit and the University Department of Medicine, in which Dr George McNicol had supplied the experimental streptokinase (see Medicine, Royal Infirmary).

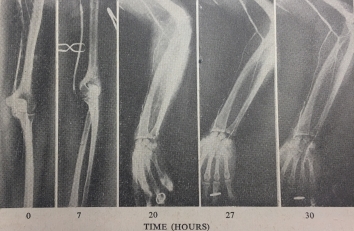

The world’s first arterial thrombolysis. A catheter instilling streptokinase was advanced from the brachial artery to the palmar arch over a weekend. Serial arteriography demonstrated successful thrombolysis3.

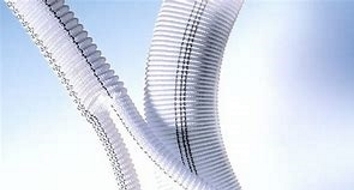

In the late 1960s cardiovascular surgery was developing rapidly, particularly in Houston, USA. John Pollock was sent in 1969 - 1970 to work with Drs Michael DeBakey and Denton Cooley at a time when these two pioneering cardiovascular surgeons were better known than rock stars. They were performing the very first heart transplants, and any such operation that took place appeared on the same evening on the television news across the world. DeBakey and Cooley were manufacturing their own vascular grafts in the USA out of Dacron (polyester).

Pollock returned from Houston and was appointed to the vascular unit in 1970. He felt that the UK should make its own artificial vascular grafts, and approached Coats Paton, thread makers in Paisley, who initially rejected the idea. However, Mr Reid was a friend of Jack Paton, the Director, and Pollock was invited back.

Research began in 1978 with work at the famous Anchor Mill, Paisley. A specialised knitting machine was built and delivered from Germany.

John Pollock operated to implant their very first aortic graft in Glasgow Royal Infirmary in 1982, and a new company within Coats Paton was formed, called Vascutek (now Aortic Teruma). Graft technology improvements meant that softer, knitted and sealed grafts could be implanted, which were easier to surgically sew in, and saved blood loss and time. Vascutek has become one of the leading cardiovascular graft companies in the world. Today, the factory at Inchinnan alone has a workforce of over 800 people. It has won eight Queen’s awards for industry and innovation. Literally millions of patients have had Vascutek grafts implanted4.

In the early 1970s, John Pollock arranged for Denton Cooley to be awarded an Honorary Fellowship of the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Glasgow (He was made a Fellow on 12th April 1980). The College was overflowing with people and excitement that evening.

The Royal Infirmary vascular unit had a 1.9% 30 day peri-operative mortality rate for elective aortic aneurysm surgery in 254 patients between 1971-1975, which was the best published result in the world at the time. Paul Lieberman and Douglas Gilmour subsequently joined the vascular surgery unit. From the 1970s, the unit continued its collaborations with the University Department of Medicine, Royal Infirmary (Gordon Lowe, Professor of Vascular Medicine), studying the contributions of blood viscosity and coagulation to vascular disease as well as treatment with vasodilators, anticoagulants and antiplatelet agents (see Medicine, Royal Infirmary).

Vascular surgery flourished in Glasgow, and another unit which had a special interest in vascular surgery also developed at the Western Infirmary. This was led by Mr Hugh Forrest, who had trained with Ken Bloor in Manchester. He was joined by Roger Quin and Alan McKay. Surgeons with an interest in vascular surgery were soon appointed to Stobhill Hospital (Matthew Calvert and John Smith), the Victoria Infirmary (Gavin Smellie and John Drury) and the Southern General Hospital (Gordon McBain), in addition to the surrounding district hospitals. Anaesthesia of frail and elderly patients with vascular disease was an art in the early days, and the techniques of surgery had to be at their best. Notable anaesthetists for vascular surgery were Bill Jones and Donald Brown.

Aortography, while initially performed by vascular surgeons, was later performed by radiologists. Skilled interventional radiologists introduced “endovascular” treatment, initially with balloon angioplasty. This was led by Dr Nimmo McKellar at the Royal Infirmary, and Dr Ramsay Vallance at the Western Infirmary. Balloon angioplasty was successful in relatively few patients, however, because of resistance and recoil of the diseased artery. When the metal Palmaz stent was invented, the situation changed dramatically, and endovascular surgery became a real alternative to open reconstructive surgery.

Recognising the advantages to the patient of endovascular treatment, John Pollock and Allan W Reid, Consultant Radiologist (and William Reid’s son) raised £1 million and built an endovascular suite in Theatre K at the Royal Infirmary. This combined a powerful ceiling-mounted x-ray facility above the operating table to guide treatment.

Many “firsts” were performed here with the important support of Sister Janice Simpson and her nurses, as well as radiographers. While William Reid had performed the first aortic aneurysm operation in the UK, his son and John Pollock 40 years later performed the very first endovascular aortic aneurysm repair in the country. Endovascular treatment quickly became routine for patients with abdominal and thoracic aneurysms.

Prince Philip officially opened the Endovascular Suite in 1994, and an important collaboration began with Dr Edward B Dietrich at the Arizona Heart Institute, Phoenix, USA. This foresight has been justified: endovascular surgery is now the approach used to treat over 90% of all vascular patients, while open surgery has greatly diminished. Locally, endovascular repair of 250 consecutive aortic aneurysms has a 0.4% 30 day peri-operative mortality.

At the Western Infirmary, Professor Jon Moss, Richard Edwards and others also progressed interventional vascular radiology (see Radiology).

The most recent developments in vascular and endovascular surgery have been in vascular imaging. Drs Allan Reid and Giles Roditi obtained the first magnetic resonance imaging facility in Scotland and pioneered its use in cardiovascular angiography (see Radiology). This non invasive method provides highly detailed images giving a diagnosis and treatment plan for the patients.

Intravascular ultrasound provides high definition imaging from within the vessel during treatment and it is very likely that the combination of detailed imaging and minimally invasive endovascular surgery will continue to be the mainstay of treatment in the foreseeable future.

Donald B Reid and John G Pollock

References

-

Pringle JH. Two cases of vein-grafting for the maintenance of a direct arterial circulation. The Lancet 1913; 181(4687): 1795-1796

-

Reid W, Watt JK, Gray TG. Phenol injection of the sympathetic chain. Br J Surg 1970 57: 45-50

-

McNicol GP, Reid W, Bain WH, Douglas AS. Treatment of peripheral arterial occlusion by streptokinase perfusion. Br Med J 1963; i (5344): 1508–1512

-

Reid DB, Pollock JG. A prospective study of 100 gelatin-sealed aortic grafts. Ann Vasc Surg 1991; 5: 320-324

Images provided by the authors