Nephrology

Nephrology is the branch of medicine that deals with the kidneys.

History of dialysis

Until the Second World War, a diagnosis of chronic kidney disease spelt probable early death. Many patients, young and old, succumbed. Low protein diets and control of hypertension were tried but premature death often seemed inevitable. Then, during the Nazi occupation of Holland in the 1940s, a young Dutch physician, Willem Johan Kolff (1911-1997) succeeded in the invention of the first practical artificial kidney machine.

The idea was based on the earlier observations in the nineteenth century of a Glasgow born chemist, Professor Thomas Graham (1805 - 1869). He studied the properties of semi-permeable membranes, in particular the fact that they could be used to allow separation of permeable urea from solution:-

‘It may perhaps be allowed to me to apply the convenient term dialysis (Greek dia, through and luein, to loosen) to the method of separation by diffusion through a septum of gelatinous matter. The most suitable of all substances for the dialytic septum appears to be the commercial material known as parchment. The vessel is described as a dialyser. Half a litre of urine, dialysed for 24 hours gave its crystalloid constituents to the external water. The latter yielded a white saline mass from which was extracted pure urea’ (Graham, Liquid Diffusion applied to Analysis, 1861).

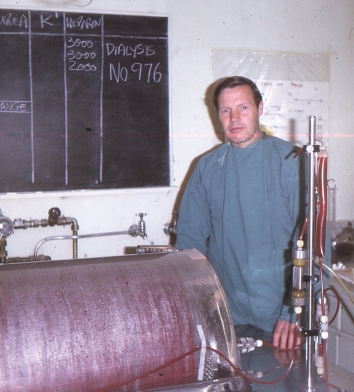

In occupied Holland, in 1943, Kolff used this property of semipermeable membranes to improvise his dialysis machine, a photograph of which is shown. He used sausage skins as his membrane. The first 15 patients with renal failure treated by dialysis died; the 16th survived.

Stories of these heroic treatments are explained in his classic publication Kidney Failure 1946. He visited Glasgow in 1985 and is shown in a photograph standing alongside the statue of Graham in George Square.

Early Pioneers in Nephrology in Glasgow

By the late 1950s, a young enthusiastic physician in the University Department of Medicine in Glasgow Royal Infirmary, Dr Arthur Colville Kennedy, was interested in dialysis. Renal disease was not being actively pursued by any of his Glasgow colleagues.

At the same time, Mr Arthur Jacobs, Consultant Urologist, had received a donation of money with which he wished to set up a dialysis unit. This was to be housed in the basement of the Urology Block, which would be its home until 1974. Here it was used to dialyse patients with acute and hence potentially recoverable renal failure.

The embryonic renal unit quickly expanded. Dr Kennedy, known as ‘ACK’, was joined by Drs Adam Linton, Robin Luke and Douglas Briggs, and biochemist, Miss Mary Gray. Drs Robert M Lindsay and Marjorie Allison joined in 1966 as senior house officers in Professor McGirr’s Department of Medicine (see Medicine, Glasgow Royal Infirmary and Western Infirmary).

Dialysis of patients with acute renal failure was very labour intensive. Prevention of acute renal failure in those at high risk, especially those undergoing major surgery, was thus a major concern of nephrologists. The role of intravenous mannitol and fluids was vital. Indeed, the early mantra in GRI was ‘Examine me daily, water me when dry’ - adapted from the local florist.

Examine me daily, water me when dry

The treatment of chronic end-stage renal failure (now termed Stage 5 chronic kidney diseases, CKD Stage 5) in Glasgow did not start until 1967, after a more permanent form of vascular access had been established by surgical colleagues.

In GRI, a ‘temporary’ purpose built renal unit was opened in 1970, built over the flower beds beside a car park. Here, patients with CKD Stage 5 received regular haemodialysis. Fortunately, no one in the unit developed viral hepatitis, a disaster which befell other renal units at this time. We never re-used dialysers, which may have prevented the spread of infection.

At that time point, it was important for younger medical staff to obtain a ‘BTA’ (been to America) degree – a period of supervised research in North America. Drs Luke, Briggs, Allison and Lindsay were amongst the first in renal medicine to follow this route; Drs Jim Winchester, David Ward and Robert Mactier followed in the 1970s and 1980s. Some became permanent residents in the USA, achieving very senior posts in prestigious North American University Hospitals. Dr John Burton, however, remained in Scotland on completion of his renal training at GRI and set up the renal unit in Inverness.

The first kidney transplant in Glasgow was performed in 1968 at GRI but after this it was agreed that renal transplantation would be carried out at the WIG where Dr Linton had set up a similar dialysis facility to GRI in a side room in Dr McCluskie’s Medical Unit.

In 1972 a dialysis unit was set up by Dr Alasdair McDougall in Stobhill Hospital, which focused on supporting home haemodialysis patients and their carers.

In 1974 a new Renal Investigation Unit was funded by Tenovus to provide a ‘9 bedded’ kidney investigation unit in Ward 42 at GRI. It was opened by HRH Princess Margaret. This coincided with the development of specific techniques such a kidney micropuncture by Drs M Allison and Dr N Moss, a scientist. The laboratory was set up by Dr Allison, after training for three years with Dr CW Gottschalk in North Carolina. Using a rat model, Drs Allison and Moss studied the effects of hepatorenal failure, a common clinical scenario in patients.

The main limitation to treating patients with stage 5 CKD was the small number of hospital based haemodialysis spaces available at GRI, WIG and Stobhill. Continuous Ambulatory Peritoneal Dialysis (CAPD) was started in Glasgow at the WIG in 1979 shortly after Dr Brian Junor joined the unit as a consultant and CAPD was soon established at all three Glasgow units.

The development of CAPD in Glasgow from the late 1970s provided endless challenges (both to the peritoneum itself as well as to the health of the patient) but this form of dialysis did not require specialist equipment or assistance from specialist nurses and so led to a major expansion in the number of patients who received treatment for CKD Stage 5 in the 1980s and 1990s.

Initially only younger patients were accepted for chronic dialysis and then older patients were accepted as dialysis facilities increased and experience grew. Nurses were trained in both dialytic techniques and were responsible for providing the day to day specialist supervision of the growing population of patients on maintenance dialysis. In the 1980s and 1990s the number of patients with chronic renal failure treated by haemodialysis or continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis increased almost exponentially and the three renal units at GRI, WIG and Stobhill functioned as separate units although at any one time, one of the consultants from the WIG also worked at Stobhill.

Glasgow Royal Infirmary

Dr Michael Boulton-Jones joined the unit as a Consultant in 1975, specialising in the investigation and management of glomerular disease. Shortly afterwards Dr James Dobbie, anatomist, pathologist and clinician joined the unit and developed a special interest in the structure and function of the peritoneum. His active mind provided insights into many mysteries of renal structure and function.

Over the period 1970 – 1995, the renal unit at GRI expanded and moved to several locations around the hospital. At one point the renal clinics and renal offices were in portacabins in the car park!

Doctors came to the unit for training from all over the UK, including Dr Iain Henderson, Dr Henry Dargie, Dr Lindsay Erwin, Dr Keith Simpson, Dr Robert Mactier, Dr Nicholas Sutcliffe, Dr Jonathon Fox, Dr Graham Warwick and Dr Ilona Goddard.

Dr Henderson became Consultant in Nephrology in Dundee in the late 1980s. Dr Dargie moved to Cardiology, with great success. Dr Simpson became a Consultant at GRI with a special interest in acute renal failure in 1989, Dr Erwin became a consultant in care of the elderly and Dr Sutcliffe became an anaesthetist. Drs Mactier, Fox, Warwick and Goddard completed their MD theses before becoming consultant nephrologists in the 1990s.

Many of the members of staff at GRI in 1988 are shown in the photograph.

Back rows

Dr C Payton; Technical staff (unknown); Dietician; Dr Sutcliffe; Dr Fox; Dr Warwick.

Dr Paleau; Unknown - Nursing staff including Jo Scorah and Jackie Kuhl; Secretarial staff; Research staff (let us know if you are in the picture)

Front row

I Henderson; M Boulton-Jones; MEM Allison; A.C Kennedy; K Simpson; M Gray.

Dr Dobbie left the unit in 1983 to take up a senior research and management post with an American company involved in the development of dialysis techniques. After his retirement, he returned to Scotland and died in Glasgow in 2009.

Professor Kennedy was appointed Muirhead Professor of Medicine in GRI in 1979. He was an excellent physician, a master of good bedside medicine and an able administrator. He retired in 1990 and died in 2009.

Dr Marjorie Allison retired from clinical work in 1995 but continued to provide a teaching role for the medical students at the University of Glasgow.

The retiral of these pioneer consultants at GRI led to the appointment of local trainees, Dr Kevin McLaughlin, Dr Chris Deighan and Dr Scott Morris, as full-time consultant nephrologists.

Western Infirmary

In the late 1960s it became clear that a second renal unit in Glasgow was required to cope with the rapid expansion of renal services, in particular chronic dialysis and to facilitate the development of renal transplantation. Dr Adam Linton, was a junior doctor in the Medical Unit of Dr Alec Brown but he also became experienced in nephrology by working with Professor Kennedy. He was appointed initially to the Western Infirmary as a senior registrar in the medical unit of Dr McCluskie with the remit to develop a renal unit and after a brief period in that post was appointed as the first consultant nephrologist to the Western Infirmary.

The accommodation went through several interim phases ending with a purpose built facility in the phase 1 building which opened in the early 1970s and which consisted of facilities for general nephrology, dialysis and renal transplantation. It was agreed between the University Departments of Surgery in GRI and WIG that cardiac surgery would be developed in GRI and renal transplantation in the WIG.

As there was no surgeon with transplant experience in Glasgow, Mr Peter Bell (in later life Professor and ultimately Sir Peter), a lecturer in the WIG Department of Surgery was seconded to Denver for two years to train with Dr Tom Starzl. From the time of his return to Glasgow, renal transplantation developed rapidly. An unusual feature of the West of Scotland transplant programme was that the patients - during their initial inpatient stay or when readmitted - were looked after in the Renal unit rather than a surgical ward but with clinical supervision jointly by the surgeons and nephrologists.

This joint supervision was important in the success of the Glasgow programme while another crucial factor was the expertise of Dr (later Professor) Heather Dick who developed the tissue typing laboratory and was widely recognised as a world authority in the field of histocompatibility.

Dr Linton’s period of tenure as a consultant in the WIG was brief as he was tempted by the attractions of Canada and emigrated in 1969. In his place, Dr Douglas Briggs was appointed the following year although Professor Kennedy could never understand why he should wish to leave his unit to move to a fledgling unit across the city. During the early 1970s, Dr Briggs was the only renal consultant but was ably assisted by the renal registrar, Dr Alistair Paton. However, after a few years Dr Paton succumbed to a similar temptation as Dr Linton had experienced though his destination was the USA rather than Canada.

Within the next year or two, the WIG agreed that there should be a second consultant and Dr Adrian Fine was appointed. However, he too succumbed to the lure of North America and he followed Dr Linton to Canada to be replaced by Dr Brian Junor. Fortunately, Dr Fine was the last of the emigres from the WIG renal unit and Dr Junor remained until his retirement.

The consultant staffing was strengthened by the appointment of Dr Stuart Rodger in 1985 and by Dr Margaret McMillan in 1990 and the academic staffing was augmented by the appointment of Dr (later Professor) Alan Jardine in 1995. Dr Briggs retired in 2000 and Dr Ellon McGregor was appointed to succeed him. Subsequently Drs Conal Daly, Colin Geddes and Neal Padmanabhan joined the medical team before the millennium.

The unit’s reputation in renal transplantation led to renal trainees coming to the unit from abroad as well as the UK. Many of these trainees have returned home to work as nephrologists in Greece, New Zealand and Australia.

Most of the merger of renal services in Glasgow occurred after the millennium but home haemodialysis training and support was discontinued at the WIG in 1991 and transferred to the long-term home training program at Stobhill.

Stobhill Hospital

The renal inpatient service at Stobhill was based in general medical wards until 1991 when the renal ward opened in ward 13A and the hospital haemodialysis unit moved from ward 1 to ward 13B. Dr Mactier replaced Dr McDougall after he retired in 1992 and Dr Jonathon Fox was appointed when Dr McMillan moved to work full-time at the WIG renal unit in 1995. From 1995, the long-term arrangement for consultant on call cross-cover with the WIG changed to shared on call consultant cross-cover with the GRI’s two consultants, Drs Boulton-Jones and Simpson. This collaboration between the renal units at Stobhill and GRI also included combined clinico-pathological and continuing education meetings and helped lead to the merger of renal inpatient services in wards 36 and 39 at the GRI site in 2000. Peritoneal dialysis services subsequently were also merged at the GRI site but renal clinics, a renal consultation service, and the hospital and home haemodialysis services remained at Stobhill.

Development of Renal Services in the West of Scotland

A review of renal services in the West of Scotland in 1988/1989 by Drs Briggs, Boulton-Jones and Rodger recommended that free standing renal units should be set up by Lanarkshire, Ayrshire & Arran and Dumfries & Galloway Health Boards. Subsequently renal units were established at Monklands hospital (initially led by Dr Bill Smith), Dumfries & Galloway Royal Infirmary (initially led by Dr Chris Isles) and Crosshouse Hospital (initially led by Dr Iain Mackay). These renal units have expanded and now provide all renal services for residents in their Health Boards apart from renal transplantation, which is still performed in Glasgow.

Separate reviews of renal services by Forth Valley and Argyll & Clyde Health Boards in the late 1990s (with input from Drs Boulton-Jones and Rodger) concluded that renal clinics and haemodialysis units should be established in hospitals outside of Glasgow to provide long-term renal outpatient and day care closer to patients’ homes. Outreach renal services for Forth Valley residents were established in Falkirk Royal Infirmary by the GRI unit (initially led by Dr Kevin McLaughlin, who moved to Canada, followed by Dr Deighan) and renal services at Inverclyde Royal Infirmary (initially led by Dr Geddes), Vale of Leven Hospital (initially led by Dr Daly) and Royal Alexandria Infirmary in Paisley (initially led by Dr McGregor) were established by the WIG unit. Renal inpatient care and renal transplantation for residents in Forth Valley and Argyll & Clyde continues to be provided in Glasgow.

A review of renal services in Glasgow after the new millennium recognised that the existing hospital buildings were no longer fit for purpose and hospital based medical services within Glasgow needed to evolve to provide ever more advanced treatments. There was also difficulty in accommodating a modern work life balance when there were two medical rotas across the city in a small specialty, despite the appointment of more consultants (Drs Cath Stirling, Siobhan McManus, Bruce Mackinnon, Pete Thomson, Tara Collidge and Paddy Mark) to cope with the rising number of renal patients.

It was concluded that

-

there were too many acute hospital sites in Glasgow,

-

centralisation of renal inpatients was required and

-

the absence of renal facilities in south Glasgow needed to be addressed.

The first major development was the transfer of acute medical inpatient services at Stobhill to GRI after the new Ambulatory Care Hospitals (ACHs) were opened at the Stobhill and Victoria Infirmary sites in 2009. The general, pre-dialysis and transplant clinics for all patients who were resident in north Glasgow were now provided in the new ACH building at Stobhill whilst the ACH at the Victoria Infirmary provided the same range of renal outpatient services (plus a haemodialysis unit) for residents in south Glasgow. Greater team working evolved between the GRI and WIG based units to provide follow up of transplant, dialysis, pre-dialysis and general renal patients and a renal consultation service at both ACHs.

The plan for a local haemodialysis unit in Paisley was shelved when it was decided to make the nearby Southern General Hospital the future hub for all inpatient services which were based at this site, Victoria Infirmary, WIG, Gartnavel General Hospital and the Royal Hospital for Sick Children.

As an interim plan, all renal and renal transplant inpatient beds were centralised at the WIG in 2010 after level 7 had been refurbished to accommodate the transfer of renal inpatients from GRI. When the GRI and WIG renal units merged, the Glasgow consultants decided to re-organise themselves into four clinical teams each providing outreach and inpatient renal services to a geographical area to help maintain continuity of care of patients with long-term renal disease. The four teams covered:

- Forth Valley Royal Hospital, Stobhill ACH, and GRI (yellow team)

- Stobhill ACH, Gartnavel General Hospital and GRI (blue team)

- Royal Alexandria Hospital, Vale of Leven, Victoria ACH, and Queen Elizabeth University Hospital (red team)

- Inverclyde Royal Infirmary, Victoria ACH and Queen Elizabeth University Hospital (green team).

A core group in academic nephrology in Glasgow was re-established many years after the retirals of Prof Kennedy and Drs Allison and Dobbie when Prof Jardine was joined in the 2010s by Dr Paddy Mark as Senior Lecturer and two of the renal trainees (Drs Rajan Patel and Kate Stevens) as Lecturers.

The WIG renal inpatient hub was one of the first specialties to transfer to the Queen Elizabeth University Hospital when it opened in 2014. The renal unit occupied most of the fourth floor and comprised an acute ward, general renal ward, and transplant ward in single room purpose built accommodation as well as a day area, haemodialysis area and assessment unit.

This renal service re-organisation was relatively seamless as the renal outreach services at the six satellite haemodialysis units and the renal clinics at six local hospitals continued to be provided by the same four geographically based medical teams established when the temporary renal inpatient hub opened at the WIG four years earlier. Dr Rodger, Clinical Director, co-ordinated most of the re-organisation of these Glasgow based renal services, assisted by Dr Mactier, Lead Consultant.

Development of Renal Services in Scotland

Glasgow nephrologists have made significant contributions to nephrology in Scotland by establishing the Scottish Renal Registry (SRR), the organisation of the Scottish Renal Association meetings and the training of consultant nephrologists for all of the other renal units in Scotland.

The SRR is an unique national dataset which provides a record of the causes, incidence, prevalence, distribution, methods of treatment and outcomes of all patients in Scotland commencing renal replacement therapy since 1960. The SRR was initially co-ordinated by Drs Simpson and Junor and their successors maintain the full collaborative support of all renal units in Scotland. Supported by NHS National Services Scotland, the SRR produces an annual report which summarises recent demographic data and trends in renal replacement therapy in Scotland as well as quality of care comparative audit data for each unit. The data from the SRR is also included in the annual data analyses performed by the UK Renal Registry.

Consultants elsewhere in Scotland

As well as trainees taking up consultant posts in Glasgow, many of the other renal trainees from the (Glasgow based) West of Scotland Deanery have taken up consultant posts elsewhere in Scotland, viz:

Aberdeen (Dr Dave Walbaum)

Crosshouse (Drs Mark Macgregor, Elaine Spalding, Aileen Helps and Vishal Dey)

Dumfries (Dr Chris Isles)

Dundee (Drs Graham Stewart, Samira Bell and Drew Henderson)

Edinburgh (Drs Wendy Metcalfe and Michaela Petrie)

Inverness (Drs Nicola Joss and Ken McDonald)

Kirkcaldy (Drs Annette Alfonzo and Arthur Doyle)

Monklands (Drs Bill Smith, Ilona Shilliday, Jamie Traynor and Claire Nolan)

Drs Marjorie Allison and Robert McTier

Images provided by Dr Allison (1940-2023)

Nephrology in Children

Pre 1972

In the UK, the first regional referral unit for children with renal disease was established at the Royal Hospital for Sick Children in Glasgow in 1950 by Dr (later Professor) Gavin C Arneil, together with consultant pathologist Dr AM Macdonald and a research fellow, Dr Studzinski. In the following decade, the unit published some 16 papers reporting the first series of children in Europe with nephrotic syndrome treated with various corticosteroids, culminating in the review by Arneil, in 1961, of 164 children with “nephrosis”, which also highlighted retrospectively the dramatic reduction of mortality brought about by the introduction of sulphonamides and penicillin during the late 1940s.

In the 1960s, peritoneal dialysis was pioneered in the unit in the treatment of acute renal failure which led to its later use in the management of end-stage renal failure. In 1967, Professor Arneil became the co-founder and first president of the European Society for Paediatric Nephrology, and founder and first secretary-general of the International Pediatric Nephrology Association. He hosted the 50th Anniversary Meeting held in Glasgow in 2017.

Arneil planned and supervised the development of a new renal unit in the new Yorkhill Hospital, which opened in 1971. He died in 2018 at the age of 95, having remained an active participant in studying nephrology in childhood throughout his life.

Dr Anna Murphy was appointed as lecturer in paediatric nephrology in 1969, and was subsequently appointed to the first consultant post in paediatric nephrology in Glasgow in 1972. Both she and Dr Beattie (see below) had trained initially in adult nephrology at Glasgow Royal Infirmary.

1972 to 1983

The logistical problems in the provision of renal replacement therapy for children are somewhat different from those encountered in adult practice. There are greater technical difficulties and also the need to provide a comprehensive service which addresses the problems of dependency, growth, psychosocial and educational development. This led to the view that children should be treated in specialist paediatric centres.

The basic requirements for such centres are specialist paediatric nephrologists and urologists, paediatric dialysis trained nursing staff, paediatric renal nutritionists, social workers, clinical psychologists and psychiatrists and dedicated teaching staff. Dr Murphy began the chronic haemodialysis programme in 1974. Help with the knowledge and management of the psycho-social issues in the early years of the chronic dialysis programme were afforded by Dr John Sharp, Consultant Clinical Psychologist, Dr David James, Consultant Child and Adolescent Psychiatrist and Ms Eva Mass, psychiatric social worker.

The introduction of continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD) and continuous cyclic peritoneal dialysis (CCPD) in 1976 allowed for a major change. This was driven by the fact that patients were increasingly being referred from areas of Scotland significantly distant from Glasgow. These techniques avoided the technical difficulties particularly with chronic vascular access in small children.

In 1982 Diana, Princess of Wales opened a separate Renal Day Unit funded by a generous donation of £300,000 by the British Kidney Patient Association. This facility incorporated the Department of Nuclear Medicine (of which the paediatric renal service was a high user), a dedicated renal outpatient clinic area, as well as an outpatient haemodialysis area, technical, secretarial and clinical staff accommodation and a seminar room.

1983 to 1998

Dr James (Jim) Beattie was appointed to the second consultant paediatric nephrology post in 1983. The 1980s saw an expansion of the existing multi-disciplinary approach to the treatment of complex renal disease with the development of very close working with paediatric urology colleagues (Mr Amir Azmy and Alasdair Fyfe), diagnostic imaging colleagues (Drs Elizabeth Sweet and J Ruth MacKenzie) and pathology colleagues (Drs Angus Gibson and Ainslie Patrick).This close working relationship has continued to the present day and a large number of colleagues from these services have contributed in the interim, particularly Mr Stuart O’Toole, Dr Sanjay Maroo, Dr Andrew Watt and Dr Alan Howatson.

A significant proportion of chronic renal failure in childhood is associated with underlying anatomical problems. A generous donation, by the Yorkhill Children’s Charity, set up a urodynamic/complex continence assessment service for such problems.

Dr Murphy had a long standing interest in the psychosocial aspects of chronic renal disease and was a founding member of a European Working Party on this important topic. She hosted meetings of this group in 1985 and 2002.

Acute Renal Failure Provision

Acute peritoneal dialysis was established as an effective treatment for paediatric acute renal failure in the 1960s. This was a popular option in infancy and childhood, particularly for patients with Haemolytic-Uraemic syndrome and following cardiac surgery. The advantages were simplicity, availability, relative safety and effectiveness. This technique allows a gradual correction of the metabolic and fluid derangements and is well tolerated. From the early 1990s, a new technique, haemofiltration, became increasingly accepted as a safe and effective therapy in the infant and child with multi-organ failure, as it had been in the adult population.

The introduction of percutaneous vascular access using dual lumen catheters in addition to the surgically inserted Hickman type catheters mitigated the pressure to maintain dependable vascular access. The haemofiltration service was provided for some years by the renal unit clinical staff mainly to the paediatric and neonatal intensive care units, until taken over by the intensive care staff progressively after the millennium.

From 1998 to present day

Dr Heather Maxwell was appointed as the third consultant paediatric nephrologist in 1998, having undertaken training in Edinburgh, at the Royal Free and Great Ormond Street hospitals in London, and in Toronto. The 1990s saw the further development of clinical networking with other Health Boards in Scotland. A report of a working party of the British Association for Paediatric Nephrology in 1992 focussed on the need for children and adolescents with chronic kidney disease to be managed in specialist units. This report showed that Yorkhill was the only such unit in Scotland. The networking began informally with Aberdeen from 1995, Dundee in 1998 and Edinburgh in 2001 and a Scottish Paediatric Renal Group was formed in 1998.

A paediatric renal transplant group was set up in Yorkhill, chaired by Mr Alasdair Fyfe, including Drs Murphy, Beattie and Maxwell and subsequently transplant surgeons Mr Rahul Jindal and Mr Brian Jacques. The remit of this group was to lead clinical discussion, audit and research on paediatric renal transplantation and to establish the mechanism of referral and the subsequent shared follow up of patients in partnership with other centres in Scotland. The national profile of the service was confirmed in 2002, when the Scottish Executive formally recognised Yorkhill as the national centre for inpatient dialysis and transplantation for children.

In 2005, a formal Managed Clinical Network for paediatric renal disease was launched and resulted in the development of outreach outpatient services ultimately to all Health Boards in Scotland apart from Orkney and Shetland (patients from these Boards are seen in Aberdeen) and the Western Islands (patients seen in Glasgow). In 2009, the Scottish Government confirmed the importance of this model of working for the majority of other paediatric specialty services, through the publication of a National Delivery Plan.

Renal Transplant Service

1977 saw the first paediatric deceased donor transplant and 1980 the first paediatric living related donor transplant. Mr David Hamilton undertook the surgery on both occasions. In the 40 years since the first procedure, 256 transplants have been carried out involving 233 patients, 168 deceased donor and 88 living related donor. The 100th transplant took place in December 1998 and the 200th in March 2010.

The use of pre-emptive transplantation, avoiding the need for chronic dialysis, became established in the mid to late 1990s, and nearly 20% of transplants from 2000 onwards have been pre-emptive. This development brought a big medical as well as psycho-social benefit to children and their families.

It is also important to document the involvement of paediatric urology colleagues in the transplantation programme, beginning with Mr Amir Azmy and Mr Alasdair Fyfe, from around 1995 onwards, along with the adult transplant surgeons. This was a unique arrangement in the UK at that time.

Location change for the Renal Unit

Around the millennium, a vacant ward became available on the sixth floor of the RHSC ward stack (Ward 6A). Following a substantial donation of £800,000 from the British Kidney Patients Association, this was converted into a dedicated renal (and urology) inpatient ward, co-located with a Renal/Urology outpatient department and outpatient haemodialysis unit. This first class provision remained the home of the service from 2003 until the move to the new Royal Hospital for Children in mid-2015.

Further renal appointments

Further consultant appointments

- Dr David Hughes joined the service in 2005, from a consultant post in Liverpool

- Dr Ian Ramage also joined the service in 2005, from a consultant post in Leeds, following the retiral of Dr Murphy

- Dr Ihab Shaheen joined the service in 2009

- Dr Deepa Athavale in 2013

- Dr Ben Reynolds is the most recent appointment in 2015, following the retiral of Dr Beattie

- Drs Leah. Krischock and Simon Waller also held consultant appointments in the service for a relatively short time, before being appointed to consultant posts in Sydney and London respectively

Trainees and clinical/research fellows

In addition to those trainees who returned as consultants in the service, there have been a large number of trainees who have passed through the service since the inception to become consultants in the UK or abroad. Some notable examples are

- Kieran Hayes

- Graham Smith

- Ann Durkan

- Frank Willis

- Martin Christian and Mairead Convery (paediatric nephrology)

- Chris Nelson (general paediatrics with an interest in nephrology)

- Jack McDonald

- David Tappin

- Bridget Oates

- Christine Findlay

- Hassib Narchi

- John Chapman (general paediatrics)

There has also been a series of research/clinical fellows over the years from many parts of the globe. All of this pays tribute to the foresight, energy and enthusiasm of the founder, Professor Gavin Arneil.

All of this pays tribute to the foresight, energy and enthusiasm of the founder, Professor Gavin Arneil.

T James Beattie and Anna V Murphy