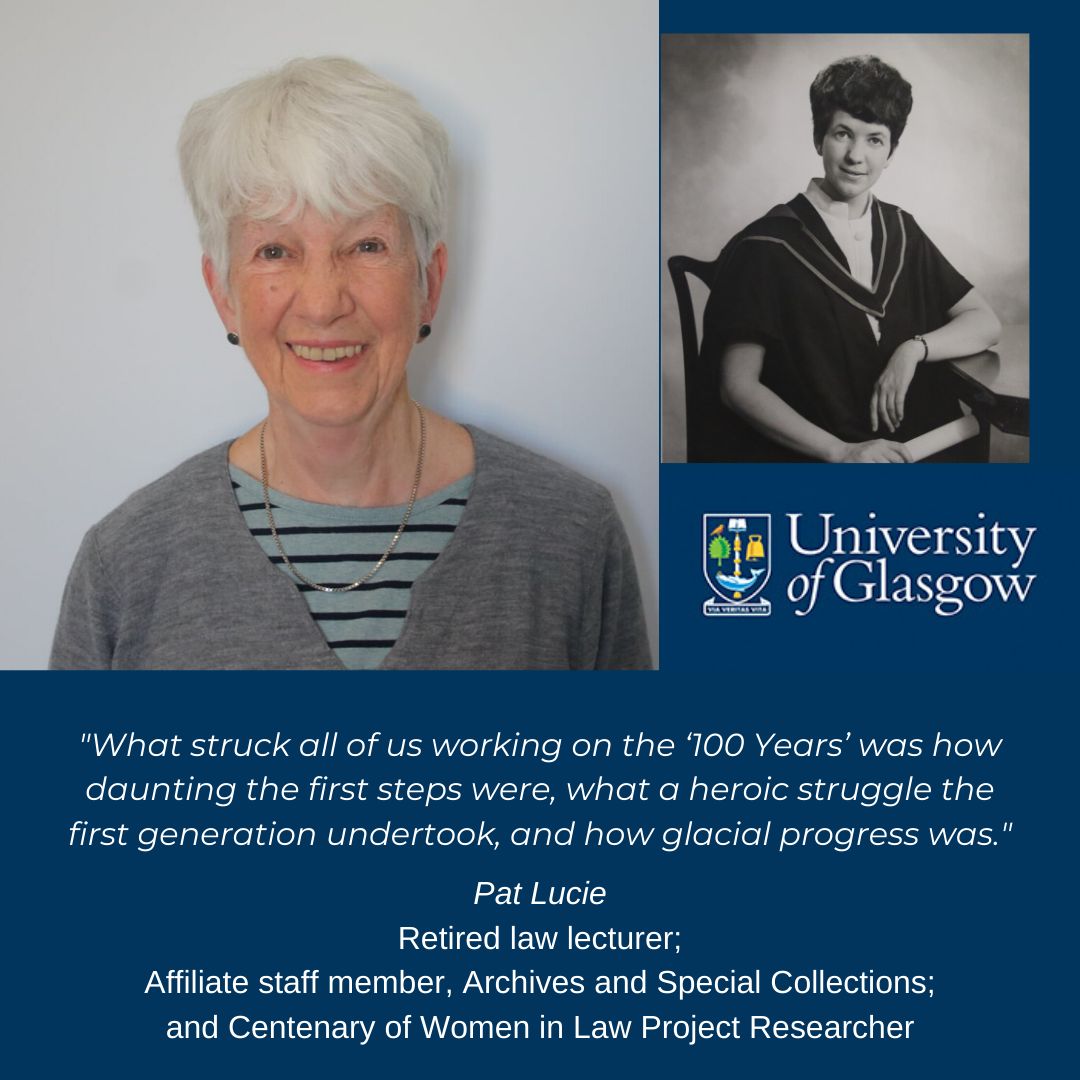

Pat Lucie

The late Gordon Cowie, Professor of Public Law did something radical in 1973, appointing a historian to teach a Senior Honours class a course on the United States Supreme Court and Individual Rights. I had experience of teaching—a lectureship at St. Andrews University in Modern History—and had completed a Glasgow PhD on American Constitutional History. But he took it on trust that I might have something to offer in a Faculty whose doors I had never entered. The students did not appear to find that a disadvantage. Their bright minds engaged enthusiastically with the subject and seminars were lively. Indeed it would be hard to argue that the judicial interpretation of the American Constitution can be approached without inviting an interdisciplinary debate. I did not feel like an outsider.

Over the years that followed it became clear that changes were taking place in the Law School and colleagues were joining sometimes passionate discussions about the nature of their subject and how best to teach and assess it. There was room for a variety of responses. As numbers of law applicants increased and traineeships contracted there was also room for the encouragement of what was known in the jargon of the day as ‘transferable skills’, including mastery of new digital skills, languages with law, team tasks and assessment, and learning through experience in Citizens Advice Bureaux, Law Centres and even Capital Punishment Defence Projects in the United States. From what I could see the traditional skills of analysis, argument and essay writing continued to be nurtured too. Jim Murdoch, now Professor Murdoch CBE, was a moving spirit in all of these projects, as well as one of my first students, and working with him on the CAB, Strasbourg, and the Death Penalty Projects was a real privilege. With the University’s film unit we made a permanent record of our students in North Carolina and Washington working with death row inmates and their lawyers. The American Project brought two exceptional people, Justice William Brennan of the U.S Supreme Court and Sister Helen Prejean, author of ‘Dead Man Walking’ to Glasgow to receive honorary degrees and address our seminar.

Gender equality was a long standing academic interest. Students in the Supreme Court class became familiar with the arguments of Ruth Bader Ginsburg long before she became the feminist icon and star of the screen that she is today. When the course began in 1973 there were no women on the Supreme Court and that only changed a little faster than the School of Law, where women remained absent from the top jobs until the 1990s. For those of us who were part-time lecturers there was no career structure and no pay scale. Like fruit-pickers we were treated like seasonal workers. Rates of pay were random and no two paid the same. For many years we were not permitted to join the superannuation scheme, an omission ultimately remedied by the European Court of Justice as late as 2000. Nor could we use the facilities of the Stevenson Building in term time. We were, however, allowed to pay the same car permit charge as full-timers. It was a matter of celebration among part-time law academics when our highly distinguished colleague Elizabeth Crawford became Professor of International Private Law.

When Maria Fletcher asked me if I’d be interested in doing a little digging into the life and times of Madge Easton Anderson, the first woman lawyer in the U.K. and a Glasgow graduate, for our ‘First 100 Years’ celebration, I jumped at the chance. Since retiring from the Law School I have been working as a volunteer in the University Archives and had already unearthed some interesting information about her activities as a ‘Poor Man’s Lawyer’ in the decade after she graduated. Through the Queen Margaret College Settlement in the 1920s she offered free advice, mainly to women in the impoverished tenements of Anderston, on problems arising from debt, family law, and housing. What struck all of us working on the ‘100 Years’ was how daunting the first steps were, what a heroic struggle the first generation undertook, and how glacial progress was. The Conference in April 2019 brought together the experience of three generations who agreed that equality was unfinished business.