Lady Hale

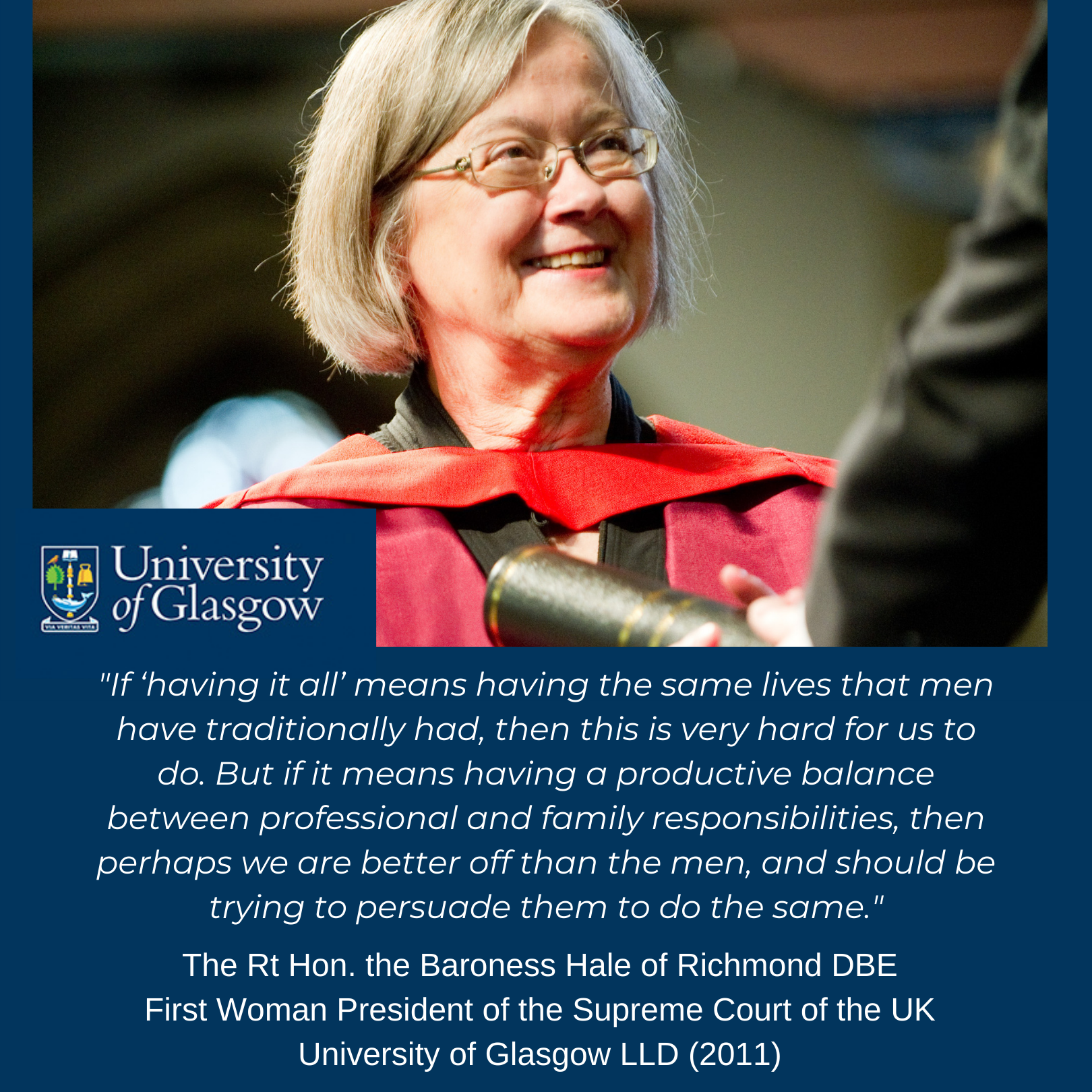

It was a great day for me in 2011 when I received an honorary LL.D. from the University of Glasgow. I am a connoisseur of degree ceremonies, having been Chancellor of the University of Bristol for 13 years and the recipient of an embarrassing number of honorary degrees (owing not so much to my intrinsic merit as to my scarcity value as a senior woman lawyer). Glasgow was amongst the greatest of those degrees and those degree ceremonies: the grandeur of the surroundings, the relaxed formality of the proceedings, the jollity of the celebrations, and, of course, the flattering things which Professor Rosa Greaves said about me in her oration.

I still pinch myself in wonder that such splendid memories are real: who would have thought it when I was a child? I grew up in a small village in North Yorkshire. My father was headmaster of a small independent boys’ boarding school. He died very suddenly when I was 13. My mother bravely dusted off her teaching qualifications – which she had had to abandon when she married my father in the 1930s because of the marriage bar - and became head teacher of the local village primary school. This meant that my younger sister and I could stay on at the local high school – a state grammar school for girls. It was a very small school, with only around 160 pupils. Neither my family, nor the village, nor the school were the sort of place where you would expect to find the top judge in the United Kingdom growing up.

But from the High School I was lucky enough to go up to Cambridge to study law – the first girl from the school to do either. Our headmistress encouraged me – because she thought that I was clever enough to go to Oxford or Cambridge but not clever enough to read history. It turned out to be the right decision. Much to my surprise, I got first class marks in each of my three years and eventually graduated top of the class in 1966. But I learned more than law at Cambridge, as I am sure that students at Glasgow have done too. In those days there were quite a few young men who came from grand families or grand ‘public’ (ie not public at all, but very exclusive) schools. They took for granted their right to be there. They also took for granted their right to a prestigious career. Some of them were not as good at law as I was. They raised my sights. I gave up the original plan to come back to Yorkshire and become a solicitor with a small to medium-sized local firm. I toyed with becoming a solicitor in a ‘magic circle’ London firm. But the corporate culture did not suit this naïve and idealistic country girl.

Teaching law at the University of Manchester offered me the best of both worlds. Here was a world class University with famous Law Professors whose books we had read as undergraduates. Here was a city which was, in many ways, the English equivalent of Glasgow, lousy weather but memorable for many exciting things – such as the Peterloo Massacre, the Pankhurst family, and splitting the atom. Best of all, the University wanted me to qualify as a barrister and do some part time practice alongside my teaching duties. That was possible in those days. I purchased a self-tuition correspondence course from the College of Law and studied in my attic flat over the long vacation after my first year of teaching. I passed the Bar exams in September 1967, even coming top of the list, which shows how very easy the exams were then. I found pupillage and then a tenancy in Manchester chambers – the Northern Circuit, consisting of chambers in Manchester, Liverpool and Preston, was then and is now bigger than the whole of the Scottish Bar.

So for a few happy years I was able to combine a general common law practice – doing small civil, criminal and family cases – with teaching a large number of subjects to the University students. I enjoyed them both. But eventually I had to choose. The practice got in the way of the research and writing which all academics must do to make progress. The teaching got in the way of taking the longer and more difficult cases which all barristers must do to make progress. Why was I so keen to make progress? Probably because the senior barristers in my chambers and the Dean of the Faculty of Law were telling me that I could not go on doing both if I wanted to get on. A key factor in the choice was that my husband was also beginning to make a career for himself at the Manchester Bar. Academia had three advantages: it was not very well paid, but it was paid regularly, and with fringe benefits such as sick leave, maternity leave and a pension, none of which applied to self-employed barristers; it did not mean getting a brief at 6.00 pm for a case in a far-flung county court early the next morning, with the ever-present risk that my husband might have been briefed on the opposite side; and it was a great deal easier to combine with having a family, which is what we both wanted. And so I chose to become a full time academic, never dreaming that I might eventually become a judge.

Having chosen to become an academic, I did have to get my academic show on the road – we have to be intellectual entrepreneurs if not commercial ones. Quite without plan, everything I chose to do led directly or indirectly to a public appointment and eventually onto the bench. I wrote a book on Mental Health Law which led to my first judicial appointment as a presiding member of Mental Health Review Tribunals. I was a founding editor of a learned journal on Social Welfare Law which led to my becoming the welfare and mental health expert on the Council on Tribunals, which in those days kept a watchful eye over all the myriad tribunals set up to adjudicate disputes between, usually, the individual and the state. This in turn led to my being asked to become an Assistant Recorder – a part time judge hearing civil and family cases in the county courts and criminal cases in the Crown Court. Then I was co-author of a pioneering book of cases and materials on The Family, Law and Society, which led to my being asked to apply to become a Law Commissioner.

So for more than nine happy years I was able to combine being a Law Commissioner, leading projects to reform the law in the areas I cared most about – child care, divorce, domestic violence, mental incapacity, and many more - with being a part time judge, hearing a wide variety of cases in courts all around London, eventually including the Royal Courts of Justice in the Strand. And in time this led to my becoming a High Court Judge, a Court of Appeal Judge, a Lord of Appeal in Ordinary, a Justice of the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom, its Deputy President and eventually its President.

Who would have thought that would happen when I set out on a legal career all those years ago? Discrimination against women was both lawful and commonplace. I was educated in the days when there were unofficial quotas against women: there were less than half the grammar school places for the girls in my county than there were for the boys; there were three colleges for women in Cambridge and 21 colleges for men. Cambridge had somehow managed to avoid recognizing the women’s colleges as University institutions and giving women proper degrees until 1948, only 15 years before I went up. Women were not allowed to become members of the prestigious Cambridge Union Society until 1965. In 1960, only 2.3% of practising solicitors and 4.4% of practising barristers were women. The first woman who could call herself a judge was appointed in 1962. Women were not allowed to become members of the Northern Circuit Bar Mess, the barristers’ dining club, until 1969. Women were routinely excluded from pubs and bars. Women were routinely paid less than men for doing exactly the same job.

But there are many morals to my tale. I can think of at least four. The first is that we must never let ourselves be put off by the fear that we might face discrimination. I don’t think that I realized the extent of that discrimination when I set out on my journey in the 1960s. But if I had, I hope that it would have made me all the more determined to do my best to prove the discriminators wrong. We hear tales these days that the traditionally privileged men now fear that they may face discrimination: of course they won’t, but in any case they should no more let it put them off than we women should let it put us off. The reality is that it is not the risk of discrimination which they fear, but the risk of competition.

The second moral is that it is possible to combine a successful career with having a family, but I’m not sure that means the same as ‘having it all’. When I was a child, there was still a view that a woman had to choose. My mother had had to choose when she married in the 1930s. Most of my High School teachers were single women. But that was another thing which changed in the 1960s. We read Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique and did not want to dwindle into housewifery. But neither did we want to lose out on what the men took for granted, both a career and a family. When I married in 1968, it was definitely with a view to having children. It was one reason for choosing academia over the Bar. And along came my daughter in 1973. Manchester University was very accommodating and I was back at work full time within months. But it takes a lot to make that happen. A supportive employer is one thing. A supportive partner is another – my husband said that it wouldn’t cross his mind to give up work when he had a child, so why should it cross mine? The resources to arrange good child-care is another – we were able to employ a nanny who lived-in during the week for the first two years and a daily one after that. This is much less affordable now. But I was usually the one who could get home before the nanny had to leave and who took on most of the domestic responsibilities – not because my husband was unwilling to do so but because he was running an increasingly busy practice at the planning Bar which took him away a lot. And of course, when the time came for me to try and move on from the University of Manchester, I looked at first for posts which were not too far away. When none of them materialized, it was a major step to take the Law Commission job in London. If ‘having it all’ means having the same lives that men have traditionally had, then this is very hard for us to do. But if it means having a productive balance between professional and family responsibilities, then perhaps we are better off than the men, and should be trying to persuade them to do the same.

The third moral is that things do not always turn out as you expect them to, but that this can be a good thing. I didn’t have a masterplan. I just set out to enjoy myself – finding work to do which I liked doing, being as good as I could be at it, being on the look-out for any new challenges and opportunities which came my way, and seizing them with both hands when they did – even if, like becoming an assistant recorder, they were well out of my comfort zone. Having a masterplan can be dangerous if it doesn’t work out as expected. Not having a masterplan can work out well, but only if you make the most of it.

And the fourth moral is that women can make a difference – not all the time, for we are lawyers first and women second, but definitely some of the time. Just being there can make the workplace a friendlier place. We can challenge the casual sexism or racism which colleagues can slip into almost without noticing. We can introduce a different atmosphere into meetings and even into courtrooms. We can smile. Above all, we can bring a woman’s experience of life to arguing or deciding a case. We can recognize discrimination and inequality when we see it. We can make the privileged feel uncomfortable with their privilege.

I have also learned a fifth lesson – that there is no such thing as a free honorary degree. Very shortly after that graduation ceremony, I was back in the Bute Hall to deliver the annual James Wood lecture, under the title ‘Is it still a Man’s World? Women, Children, Citizenship and Migration’. My interest in the subject had been sparked, in particular, by the Supreme Court case of ZH (Tanzania) v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2011] UKSC 4, where we held that it was a disproportionate interference with the rights of British citizen children to remove their mother from the country when the effect would be that they would have to go too. I am proud to be a woman in law because we can stand up for the rights of women and children and make a real difference in the world.