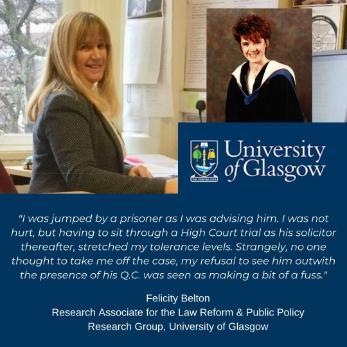

Felicity Belton

I am Felicity Belton and I currently work part time as a Research and Teaching Assistant for the Law Reform & Public Policy Research Group at The School of Law, University of Glasgow. I am also studying for a Doctorate in Law researching ‘Forced Marriage in Scotland: The Domestic Relationship with International Obligations’.

However, my relationship with UofG Law started in 1990 when I enrolled in a Post Graduate Diploma in Forensic Medicine. I was working as a criminal defence lawyer and, as I was the only member of my firm who could successfully attend post mortems (others had problems with fainting and nausea), I was seeking to expand my knowledge and expertise. Solicitors and doctors on the course were taught modules in Medicine, Science and Law and completed a dissertation. I completed qualitative research for the first time, interviewing my clients regarding changes in illegal drug use and the underlying reasons. My first experience of legal education at the University of Glasgow Law School was very practical. After graduating in 1991, I utilised my knowledge every day in court in such diverse areas as blood spatter patterns, hypoglycaemic attacks and behavioural changes linked to sleeping tablets. All of these are actual examples where I was able to provide a better legal defence to clients.

There were not many female criminal defence solicitors in the nineties. There were only two practising in Edinburgh when I started my criminal traineeship. By the time I qualified there were a couple more. We all had to cope with differing degrees of sexism from being referred to as a ’wee lassie’ by the court staff to being ‘protected’ by male QC’s refusing to show us photographic crown evidence as it was ‘too upsetting’. Surprisingly, whilst the clients could be pretty blunt and gratuitously sexist in their speech and demeanour, if they thought you were doing a good job they gave you a chance. My worst encounter was being jumped by a prisoner as I was advising him in Perth Prison. I was not hurt, but having to sit through a High Court trial as his solicitor thereafter, stretched my tolerance levels. Strangely, no one thought to take me off the case, my refusal to see him outwith the presence of his Q.C. (an imposing figure of a man) was seen as making a bit of a fuss. If you want to do this job you will have to toughen up I was told. On another occasion, one of my female colleagues decided to push back the boundaries and wear a very smart trouser suit to court. She stood up to make her submission and was told by the (male) Sheriff that he ’could not hear her’. It took her some time to establish that it was neither the volume of her voice or the Sheriff’s auditory problems. He was refusing to listen to a legal professional discuss whether or not a man should be deprived of his liberty.

I moved to Australia in 2000 and was admitted as a solicitor in Queensland. I practised in civil litigation and immigration law. I was in a very rural community and soon found out that whilst sexism towards women solicitors was reducing somewhat in Scotland, in Outback Queensland it was alive and kicking. Multiple times people I was pursuing for clients refused to believe I was a solicitor. Court Clerks did not want to discuss my cases and asked to speak to ‘the solicitor’. At times I resorted to faxing a copy of my practising certificate. In open court I was addressed as either my first name or ’Darl’. It was a bit of a learning curve. Some of the migrants and refugees to Australia were not necessarily better. I was referred to as ‘the woman’, recognition of me as equal to the male solicitors I was interacting with was quite often absent.

In 2006, when I became a single parent, I began teaching Legal Studies as the hours fitted in with family life. I got the opportunity to convince numerous young women that they could be lawyers or many other types of justice personnel. I told them stories from my time as a solicitor in both Scotland and Queensland. If I could do it so could they. Many of them have and are now practising solicitors all over Australia and Europe, hopefully combating everyday sexism.

In 2013 after completing a LL.M I graduated from Queensland University of Technology. I had been given an Equity Scholarship, which encouraged women from rural areas to complete post graduate study in law. I was still working full time and did many of the modules by distance. I received a lot of encouragement from a female professor who recognised that making the jump from practice to academic study of law was a big effort. I began doing research on trafficking and forced marriage, which became the subject of my dissertation.

In 2014, my children had both been accepted to universities in Scotland. I returned to Glasgow and applied for a job as a researcher at University of Glasgow. I did not get the job, but I did meet Professor Jane Mair. She encouraged me to apply for a PhD at the Law School, she became my supervisor and I am now in the process of writing up my thesis. During my research, I have worked as a college lecturer and for the Law Reform Research Group in the Law School. I have received support and encouragement from numerous female academics that I can transition from being a legal practitioner and teacher to a legal academic. For the first time in my career, I have had genuine support and recognition from the male legal academics at University of Glasgow Law School, in contrast to many of the male legal personnel I have encountered over the years. In my future academic career, I hope that I can provide a similar type of guidance and support and contribute to the normalising of women in law.

Attitudes to women in law still need to be addressed, it is not perfect but over the last 30 years it has improved. In the future, I hope that the forward motion of positivity towards women in law continues. That my stories of sexism in my career become a ‘her’storical reflection on attitudes long since abandoned. I also hope that the intersectional types of sexism towards women of colour, women in the LGTBQI community and women with a disability make equal progress.