Scottish Literature

Beginnings to Early Modern (1375–1501)

Course overview

This course gives a roughly chronological overview of an entire cultural period and its major authors and themes. Starting with historical epics that have strongly political and chivalric emphases The Brus and The Wallace (the real text, not Mel Gibson’s Braveheart version), the course then goes on to document how national culture changed into a late fifteenth-century humanist Renaissance that firmly embedded itself in a European ‘republic of letters’. It allowed for the creation of a versatile vernacular and a confident early-modern literary community in which we can trace Enlightenment beginnings as well as the material that Scots writers sought to preserve when Scotland was gradually absorbed into the United Kingdom.

Course convener Dr Theo van Heijnsbergen writes:

This course allows students to explore a relatively small-scale corpus of texts that nevertheless presents a surprising riches in terms of variety and quality, as well as genres not known from neighbouring literatures, such as the spectacular flytings (poems of abuse – like the modern-day ‘roastings’ or ‘dozens’ – in dialogue format), or the so-called ‘eldritch lyrics’, fantastic and often humorous poems set in a supernatural landscape. In one such eldrich lyric, the protagonist catapults himself into the night sky to escape prison, only to bump into the moon. He then falls to earth, rather disoriented, and searches for answers – but instead he finds two prophets ‘roasting strawberries on a fire of snow’. No better image of the wonderful absurdity of life and how the imagination responds to it. Roll over, Salvador Dali!

Alternative Renaissances (1513–1700)

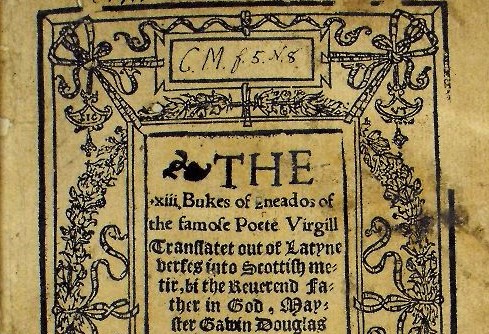

The Eneados by Gavin Douglas (1513)

Course overview

Examining separate modes of writing from the 16th and 17th centuries such as lyric, drama, narrative verse and prose, this course asks questions of cultural-literary histories of that period often imposed from elsewhere, in order to make visible developments and qualities (as well as absences) of the Scottish material, but now based on its own reference points. The texts involved are often not available in published editions but have been produced in-house, and are not taught anywhere else, making Glasgow the unique place to teach and study these texts. This strongly research-led teaching allows the more adventurous students to work ‘at the frontiers of knowledge’, often with original manuscripts and early prints.

Course convener Dr Theo van Heijnsbergen writes:

As a foreigner to these shores, I find it extraordinary how this period is still represented, even in some academic corners, in terms of ‘Knox vs Mary’ (Queen of Scots), or witches and covenanters. This course, in trusting informed students to work with as-yet-unpackaged textual material, asks students to interrogate established critical-cultural narratives and replace them by better informed ones.Near the end of the course we look at a few pamphlets and the first ‘newspaper’ produced in Scotland c. 1661. One of them describes how Prince Tomambeio Dionigi Cuoulato Pazzeio, Prince of Tartaria, has arrived on the Scottish east coast with a fleet of 3000 ‘gondolas’. He comes ashore to inspect the uncouth but jolly natives, in a wonderful inverse parody of how West European ships approached especially African shores. But has this strikingly early example of ‘The Empire Strikes Back’ (or even its author, who was a newspaper editor, translator of Cyrano de Bergerac, playwright and theatre director) ever received any literary attention in Scotland? Nope. Until a student who did the ‘Alternative Renaissances’ course wrote her dissertation and then an article on this text, which was published this summer in a peer-reviewed journal. This has also helped her acquire SGSAH PhD funding, an example of how research-led Honours study in the rich inter-disciplinary set-up available in a ‘traditional’ university such as Glasgow can yield real dividends for students.