Out of Ashlaa’ أشلاء: Refugee Language Education in Times of Heartbreak and Failure

Published: 11 September 2025

Keynote presented at the BERA Conference, 10 September 2025, University of Sussex, by Alison Phipps, Khawla Badwan and Hyab Teklehaimanot Yohannes.

Authors:

Alison Phipps, Professor of Languages and Intercultural Studies UNESCO Chair in Refugee Integration through Languages and the Arts (Culture, Literacies, Inclusion & Pedagogy).

Khawla Badwan, Reader in TESOL and Applied Linguistics, Manchester Metropolitan University

Hyab Teklehaimanot Yohannes, Lecturer in Forced Migration and Decolonial Education at the University of Glasgow, researches decoloniality, poetics, and political theory.

Alison: Failure and Heartbreak

Trigger Warning: Genocides; Trafficking; Incarceration; Torture; Hope

The Arabic word ashlaa’ refers to scattered body parts and dismembered flesh and bones. (Shaloub-Kevorkian, 2024)

This joint keynote is delivered from within the physical bodies of three educators and researchers – Hyab, Khawla, and Alison – who are fearful, experienced, and clear. We speak from Édouard Glissant’s “open circle” (Glissant, 2009), knowing that these times demand more than one voice in plenary, and that education must once again become a poetics of relation.

We speak in the aftermath of the provisional orders of the International Court of Justice (ICJ, January 2024), and following the United Nations’ declaration of an official famine in Gaza this summer. We speak at a time in the United Kingdom when small, extreme, far-right protests receive unprecedented media attention and accommodation, and when the UK Government uses language which no educator aligned with UNESCO’s values of peace education could ever justify. We speak after the First Minister of Scotland stated: ‘Let’s be clear – a genocide is unfolding in Gaza as a result of Israel’s actions’, and instituted a military boycott, in accordance with the International Court of Justice orders.

When we wrote the abstract for this plenary earlier this year, it was during a period of forced starvation and the expulsion/ ethnic cleansing of a people. Around 88,000 students and 3,000 educators in higher education in the Gaza Strip were searching through the rubble for the remains of their working lives: their students, their colleagues, their books, their universities. Famine had yet to be officially declared, though the painstaking work of investigation was ongoing. 90% of schools were already severely damaged, according to assessments by the United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA), which was soon to be banned from operating at all, let alone educating, Palestinians in the Occupied Palestinian Territories and the Gaza Strip.

We must now update those figures, increase the percentages and the numbers, even as we also face what is – scholars agree – the tenth stage of genocide: denial. UNRWA has now been banned from operating. A private company, The Gaza Humanitarian Foundation, distributes aid while reportedly shooting at those to whom the aid is distributed.

Education is profoundly disrupted. Higher education infrastructure has been erased. My (Alison’s) colleagues of 15 years are eating one meal every three days. In Zoom conversations, as we attempt to enable education in an emergency, we see their homes shake with bombardments. We hear drones. One of my PhD students, awaiting evacuation, has been displaced 14 times and submitted her CARA scholarship application from the roof of a four-storey building, under gunfire.

In Ukraine, the Russian aggression rages on. The death toll rises. Ukrainians in the UK start their own language schools for their children, joining many others that form the informal refugee language education landscape. A few Sudanese, Eritrean, Afghan, Ethiopian, and Congolese refugees make it to the ‘hostile UK’ on boats, fleeing from persecution and war, landing to be greeted by the mania of xenophobia unleashed as mob, and draped in the flags of the land. What awaits them is a broken asylum system, requirements to learn English, and an ESOL system that is chronically underfunded.

Meanwhile, Community ESOL – the euphemism for what happens when those failed by the state begin to do the work themselves, for themselves – is offered as a policy solution. Maybe it is, maybe it is where the ‘menace of hope’ pulses on, restoring life.

Each of us presenting together today has been unmade and remade through refugee experiences of differing kinds, and now, profoundly, through the Gaza Famine and Gaza Genocide. We have experienced our spirits, our bodies, our languages as ‘ashlaa’ (أشلاء ), shattered fragments. For Alison, during previous aggressions, it was the metallic taste of fear mingling with the sound of drones, bombings, and evacuations. For Hyab, it was at the hands of traffickers and torturers during his search for refuge, and in his work protecting victims of the same. For Khawla, it was the bombs that shattered the broken windows and half-standing walls of her home in Gaza, and the silence that denied these war crimes. The erasure of her people’s past and present and the banning of a just future for Palestinians in their land. All of this taking place in the void and absence of discussion in spaces like this.

For Hyab and Alison, Gaza is not the only context of forced displacement and war crimes under international law. We have family and colleagues in Sudan, Eritrea, and Egypt. Alison is involved with both the Scottish Government’s and the community’s responses to the Ukraine Humanitarian Resettlement Schemes, and with the Gaza student evacuations. And for all of us – as language is torn apart, propagandised, its meanings placed under erasure – we live and breathe the multiple failures and abyssal realities of refugee experience, which tear us apart day in and day out. We are profoundly acquainted with grief. It is from this place, which makes a mockery of any educational research claims to objectivity, that we insist on speaking through the ashlaa’ of our experience, and from within the pedagogies of language education in times of failure and heartbreak.

Nadera Shaloub-Kevorkian, an anthropologist writes:

Centering ashlaa’ unsettles the totalizing perception of annihilation by insisting on burials for the dead. It makes meaning out of the loving acts to collect and protect the scattered dead; to re-member the dismembered (Shaloub-Kevorkian, 2024)[i]

Whilst our bodies respond with the thudding effects of trauma, past and in the present, we are not ashlaa in the sense Shaloub-Kevorkian writes of. Our minds, words and spirits may scatter repeatedly but our bodies are more or less intact. We are alive. We are witnesses. We are educators and researchers.

Ashlaa as a concept enables us to undertake our work. It is a concept that articulates with integrity the experience of all those whose languages are forced into monolingually framed curricula, whose families are now denied reunion, who are scattered parts of the familial body. Ashlaa’ – scattered, and torn – are the words we are denied, the words which lose their meaning under directives and contestations about the abyssal realities and wounds out of which refugee language education must be constituted. When crow-barred into the discourse of liberal education, these are bound to fail.

The old certainties of consensus surrounding liberal education and liberal peacebuilding are in tatters; teachers and learners are at once cast adrift, unmoored from the language, discourse and proper forms of orderly, peaceful pedagogies which they have been taught can make them safe.

Policy to Poetry

Transfer the knowledge.

Bank the education.

Roll it out,

roll it out I tell you

across China.

Fill the seven seas

with these words

these my words

and these way

these my ways.

May all be

competent

efficient

competent

professional

efficient

competent

Yes. I repeat. Professional

competent.

It is our settled will

that having settled

our will

we settle for

competence

efficiency

professionalism.

This is the policy.

Ours.

Our policy.

This will deliver.

This will deliver up

a curriculum for excellence,

standards for success.

And across the Seven Seas,

across seven,

there will be

competence between

us. And excellence

and ceaseless

efficiency and

professional success.

And between us

there will be success, I say.

Standards.

Quality.

And of the rolling out

there will be no end.

In place of rest:

efficiency.

In place of beauty:

excellence.

In place of diversity:

national standards.

In place of brokenness

and the tenderness

(which is learning’s due):

quality’s roar.

In place of dancing:

rolling out.

And there, look, in the

path of the excellent rollers:

violets.

there were […]

crushed […]

now […]

(Phipps & Saunders, 2009)

Alison: Educating to Destitute the Structures of Violence

‘“If wars are made in the minds of people”, says the UNESCO founding document, “then it is in the minds of people that the defences of peace must be constructed”. This begins with language. The late great scholar, Walter Brueggemann says, that the ‘script of therapeutic, technocratic, consumer militarism that socialises us all, has failed. It cannot make us safe and it cannot make us happy.’ (Brueggemann, 1999)

As such we insist here on destituting the structures of violence in our educational language systems and discursive regimes. We dust ourselves down daily in order to show what we have researched and know, again and again, that Freire’s pedagogies of hope and freedom can be made, even here (Freire, 2003, 2006). These pedagogies and their adaptations can unstick us from the ‘sticky knowledge’ and ‘valuable skills’ discourse that underpins the reality of paralysis and fear, and through learning and unlearning, create oases of education as sanctuary. Each of us has gathered examples through our research over many years with refugees and as refugees, and especially with Gaza. These examples demonstrate the possibilities of pedagogies beyond the abyss, pedagogies of care, lexicons of love, and purposeful decentring of power, with humour and beauty.

As UNESCO Chair for Refugee Integration through Education, Languages and Arts it’s my job to understand the structures which enable life to carry on beyond the violence and persecution of what Hyab terms, in his new book, The Refugee Abyss. UNHCR in particular have worked with governments worldwide to set standards and offer examples of good practice for refugee integration in education. 15 by 30, for instance, refers to the aim set in the Global Forum for Refugees of having 15% of refugees in higher education by 2030. These are a starting point but it’s in schools, informal education in communities, in universities and colleges in the community language classes run by people like “ESOL Lynda” and in insistent multilingual, that practical pedagogies of hope, of inclusive expression, of utterance beyond the unutterable are fostered.

Pedagogies are practices, they need modelling. We cannot talk about decolonial or decentred education, or anti-genocidal education without practicing it and so I am delighted that BERA – after some persuading – agreed that I might do this, with the privilege of my invited plenary, and ask two experts with profound experience that is alive with the violence, the heart break and the failure, to share their research on language education as, with and for all who are profoundly unmoored and exiled from the certainties and normality of life in this moment, and as part of serving education with refugees.

What, in such a time of failure, aporia and heartbreak, is responsible educational research and teaching? What might a pedagogy of heartbreak look like? What are the pedagogies of the abyss? And from whom might we best learn?

Hyab: Pedagogies of the abyss

In addressing the pedagogies of the abyss, I offer three preliminary reflections.

First: naming the world from the position of the refugee.

For us, refugees, education begins by naming our condition. It begins by speaking from a place of dispossession, from the voice of a displaced people who have nothing left to lose, having lost everything, including faith in what this world offers. Such naming gestures towards what might be called a pedagogy of the abyss, a pedagogy of open wounds and scars, expressed in crying, wailing, bearing witness and lamenting. Yet, it is not merely a lament for one’s own condition, but for the condition of a world that has become violent, indifferent and unliveable. Epistemically, pedagogy of the abyss is about connecting traces of survival and piecing them together in a transcendent relation beyond the abyss.

The condition that befalls refugees is what we have elsewhere named ‘the refugee abyss’ (see Yohannes 2026). This abyss begins the moment one becomes a refugee, a status in which the only right is the right to endure rightlessness, or to perish without rights. Let me illustrate this with the stories of three friends: Abraham, Sara, and Hassen. These are not their real names, but their story is true, and it is shared by hundreds, if not thousands, of other refugees.

Abraham, Sara, and Hassen survived arbitrary detention, endured indefinite national service, and lived under the constant threat of war in Eritrea. Under such conditions, fleeing their homeland became a necessity. During their escape, they were kidnapped by traffickers while crossing fortified borders. They survived refugee trafficking, ransom extortion, torture, sexual violence, and the possibility of organ harvesting.

Wounded and weary, they reached Cairo with their pain still raw. There, they sought asylum. The registration process took nearly two years. Amid this long and uncertain wait, a glimmer of hope appeared in the form of resettlement to the US through a community sponsorship initiative known as Welcome Corps. The programme allowed a group of five, including family or close friends, to support an application for resettlement.

With the help of friends, all three submitted their applications. After months of vetting, they were granted visas, with flights scheduled for February 2025. As part of standard procedure, they closed their UNHCR files and secured exit visas from Egypt, marking the start of what they believed would be a new life. Bags were packed.

Then Trump came to power. As is now well known, his administration defunded resettlement programmes and cancelled all refugee visas. The friends’ hopes collapsed. Their UNHCR files were closed, their legal presence in Egypt revoked, and their resettlement visas cancelled. They were arrested and detained by Egyptian authorities before being deported to Eritrea two weeks ago.

These refugees are stripped of the place where they once sustained their physical existence; they are stripped of sociality, language, and belonging, and their bodies are reduced to violable, killable, disposable corporealities. Fanon (1986) calls this condition a rupture that separates the body from its humanity, and murders the latter, leaving only flesh and bone exposed to the abyss. In his words, this results in ‘an amputation, an excision, a haemorrhage that spattered [the] whole body’ (Fanon 1986, p. 85). What remains is not a life, but an amputated body staring into its own grave.

The grave of humanity that Fanon had in mind was the Atlantic Ocean, the slave ship, the plantation, the colony, the metropole. Today, that grave is the Mediterranean, where thousands vanish without trace. It is the ‘asylum colonies’ disguised as refugee camps, shantytowns, hotspots, temporary shelters (Yohannes et al. 2024). It is Gaza, an ongoing colony where genocide unfolds before our eyes. It is Sudan, Ukraine, Yemen, Syria, Myanmar, and so many other places. These are the new graves of humanity. They map the coordinates of the abyss, the very sites where the violence of forced displacement unfolds with impunity.

The condition of the refugee abyss is often spoken using grammars of coloniality and raciality. These grammars construct the figure of the refugee as nameless, as threat, as one whose presence justifies punishment without consequence. We are told we are ‘invaders’. But no one speaks of the doctors, nurses, carers and essential workers among us who sustain life. We are accused of ‘bringing disease’. But that is a lie, and I bear no burden to prove it false. We are not here to build an ‘island of strangers’. We are here because bombs and sanctions from islands like this one, in collusion with the regimes of their former colonies, have made us refugees.

Yet, such grammars are endless. They constitute the syntax and structure of un-naming. They weaponise law, mobilise public fear, racialise bodies and dehumanise lives. They refuse to name the structural violence that produces the refugee abyss. Instead, they impose names we are not meant to question, names designed to control, contain and dehumanise us. As the world order trembles, we are cast into the abyss, along with all life forms and the fragile conditions that make life possible, pushed to the very edge of erasure. Those of us who have survived this far continue to ask: ‘Does the world know we exist’ (Yohannes 2026, p. 1)?

Second: the praxes of ruderal existence

Beyond the naming of the abyss lies a slow, tedious, and often exhausting yet life-affirming restorative praxes of ruderal existence. Such praxes create the conditions of possibility for preserving life, for making movement possible, and for restoring dignity in the wastelands of coloniality (Yohannes 2024). It emerges in the cracks, in fugitive spaces, in places where life begins anew, in shadows, undergrounds, and beyond the dehumanisation of unwanted names.

Our first task, as refugees, is to learn how to preserve life for as long as possible. The preservation of life is inseparably bound to movement. For us, to move is to find the cracks, to create new ones, and to clear paths for survival in the face of the abyss. This knowledge of limits and ruderals enables us to move, to step away from violence, and to drift, however precariously, towards safety and dignity, even when our lives remain exposed to the risk of perishability. The elasticity, secrecy, and fluidity that such movement requires demand that we become multiple in countless ways. In this movement that makes preservation of life possible, knowledge becomes an embodied praxis of ruderal existence. The question, then, is this: how do we arrive at a position of possibility for knowledge and relation, beyond masks, beyond naked bodies? Importantly, how do we move with that position as it shifts and mutates? How do we change alongside it?

We do not yet have answers to these questions. Instead, we sit within what Glissant (2009) calls the ‘open circle’ of the known and unknown, celebrating its irreducible communion while curious of its obscurities and remaining respectful of its opacity. In this act of sitting that resists settling, we follow Glissant in placing relation before ontology, recognising that the unknown exceeds any fixed positionality, spatiality or temporality. To place relation before ontology is to unsettle ontology itself, to disrupt its Heideggerian fixation on ‘being and time’ (Heidegger 2007). It means we are less concerned with what something is (its nature or essence) than with how it relates to others.

To invoke the unknown is to attend to that which lies beyond understanding or conceptual grasp. Attuned to the infinite ungraspability of the unknown, we do not merely acknowledge the ineffable, the sublime, and radical alterity. We embody humility and openness towards what cannot be fully known, measured, defined or categorised.

Let me offer, by way of a practical example, a glimpse into the archives of the Eritrean coffee ceremony, with its intimate stories and everyday sanctuaries. This traditional ritual plays a central role in the socio-cultural life of Eritrea and its diaspora. It is not about drinking coffee, but about enacting hospitality, community, and relation.

The ceremony typically unfolds in three stages, each imbued with symbolic meaning.

The first is preparation. Green coffee beans are washed, then slowly roasted over charcoal or, more recently, on an electric stove. The person leading the ceremony, often a woman in traditional dress, roasts the beans with care and rhythm, allowing the aroma to rise. The scent is wafted towards guests, inviting them into presence. The beans are then ground, traditionally by hand using a mortar and pestle, though electric grinders are now common. The coffee is brewed in a jebena, a traditional clay pot, with ground ginger and water, and brought to the boil several times until ready.

The second is serving. Small cups, called funjal, are used, and the coffee is often accompanied by snacks such as popcorn, roasted barley, or traditional bread. It is served in three rounds, each with distinct significance. The first honours wisdom and respect, and is offered to elders and guests. The second deepens the bond of hospitality. The third opens a space for sharing reflections.

The third is the praxis of sharing. Here, the ceremony becomes a site of care, storytelling, conflict resolution, and the nurturing of justice. Family, friends, and neighbours gather to speak of daily struggles and dreams, of politics and spirituality.

The coffee ceremony holds space for both loss and life. It is a meditation on the cycles of time, a restorative and generative space for imagining the otherwise. Its poetic principles of non-exclusion, understood as an invitation to radical openness, and of nonviolence, are grounded in relation. Such relation opens an aperture into positions of possibility, of sanctuary, of hospitality, and of refuge beyond the abyss.

With families, friends, and strangers gathered in an open circle, facing one another, there is an invitation to shed our masks, to turn our generative capacities towards the unpredictable, the emergent, and the poetic, and to drift towards the infinite threads of relation between humans and more-than-humans, and their interdependence. It is an invitation to drift towards what Fanon calls a relation of ‘transcendence’ (1986, p. 138).

Third: language and the pedagogies of the Abyss.

In the refugee abyss, language is often among the first casualties. Forced displacement strips refugees of their mother tongues, followed by the slow violence of forced assimilation, often disguised as integration. They are denied the right to speak, to name, to remember, or to write in the languages that once carried their heritage.

As a former refugee and parent, I dwell at the border between carrying my ancestral language forward and witnessing its slow death. Each lost word marks the slow extinction of a world. This is not merely the fading of grammar or vocabulary, but a linguicide that erodes our capacity to name the world and renew our rituals. With the loss of language, the essence of ceremonies like the coffee ritual begins to fade. Without words, they lose their breath, rhythm of life, and soul.

Fanon reminds us that ‘…to speak is to exist absolutely for the other’ (1986, p. 17). But in what language do we affirm this existence when no language remains? In what language do we address the other, whose precarious being demands our speech and whose gaze unsettles our own? Can a language founded on denial bear the weight of responsibility, relation, and care? Can it witness a world trembling beneath forced displacement, genocide, and erasure?

How do we speak to the other whose otherness we have marked and distanced, whose humanity we have torn apart in silence? Or have we become so fluent in silence, so rehearsed in refusal, that we no longer remember how to exist for the other at all? And what becomes of education, this broken promise, when it no longer speaks to the ethical, political, and existential? What remains of education when speaking has lost its relation to the other?

I leave you with these questions, for questions are what remain when existing systems of knowledge fade into obsolescence.

Khawla: Pedagogies of Care: Moving forward with Grief and Heartbreak

Please allow me to go back to basics. To beginnings as Edward Said (1975/1985) instructs us to do in order to ‘stimulate self-conscious and situated activity, activity with aims non-coercive and communal’. I here stand in front of this BERA audience, and I ask: What is education for? What are we educating towards?

I am sure many people in this room as well as many outside this room will have different views on this matter. Politicians, in particular, are very concerned about education which is packaged in terms of targets, hubs, inspection reports, and league tables; all devised to see education as a coercive space reduced to sticky knowledge, as Ofsted likes to call it, and valuable skills, as the Department for Education, likes to remind us.

I am sure I am not alone in taking issues with this reductionist, harmful vision for education. In addressing the question, what is education for? I would like to draw on Jackson’s (2011) view of education as a moral enterprise at root. This view needs to be the most prominent view especially in times of genocide and failures. This is because if we fail to see education as a moral practice and educators as truth tellers, ‘[t]here remains no driving and unifying ideal, no coherent set of values from which to engage morally and critically with the powerful agencies which seek to use “education” for their own material or political ends’, Pring (2001: 102) argues.

We are here, asked to educate with no values and with complete disregard for international law and the post-World War II order, including the Universal Declaration for Human Rights (1948) that guarantees a right to life, liberty and the security of person (Article 3) and including The Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (1948).

We are here with no unifying ideals, stuck in discourses of denial and the pretence of impartiality, wondering what to call the mass killing of an entire trapped civilian population, enabled by our own government, funded by our universities that are operating in genocidal mode’ under claims of research neutrality while remaining ‘structurally dependent on settler-colonial collaborations and funding’ (Albanese, 2025: Item 90), and brushed under the carpet of silence and silencing.

We are here with no coherent set of values that enable moral engagement with the necropolitics (Mbembe, 2003) of creating death worlds. The death worlds in Sudan, Ukraine, Congo, Afghanistan, Palestine, and the live-streamed death world from Gaza that has been, so far, hit by bombs equivalent to six Hiroshimas (Rogers, 2025), more child deaths than any other conflict, and with the highest number of child amputees in the world (De Vogli, et al., 2025).

The genocide in Gaza affects us all. It affects all social aspects of our lives. It hits us in the core of what it means to be human and to stay human in times characterised by moral blindness and apathy. Make no mistake. The genocide in Gaza is not an unfortunate event in a faraway strip of land. It is a place brought to every corner of the world through unprecedented economic, technological and military entanglements. If Gaza were a crime scene, Francesca Albanese (2025) warns us, Gaza would have all of our fingerprints all over its rubble.

My contribution here centres the Genocide in Gaza as an exemplar of the failures of so many systems and orders, including education. We have failed to prevent genocide when we turned our backs on the cultural manufacturing of genocide that legitimises anti-Palestinian racism, hatred, White supremacy, land theft, and coloniality. Rather than surrendering to hopelessness and despair, I here urge you to let this failure be a catalyst for worlding education with Gaza. We can re-world Education right here. Together. From this very room. At this very specific annual conference of educators.

I know many of you are scared, hesitant, doubtful, even lost.

It is safer to cling to the familiar. The business as usual of ignoring the genocide in Gaza. It is easy to put our failing theories, language, systems and orders on ‘life support because we fear the void left in their place’ (Machado de Oliveira, 2021: 15). No more.

Let us remain in agony, with the focus to re-world education. Agony is important. ‘[t]o remain human at this juncture is to remain in agony. Let us remain there: it is the more honest place from which to speak’, as we learn from Hammad (2024:60).

To live life

a genocide away

except it’s not away

And there’s no away

But there’s only one way

To speak up, show up, stand up

To do well, live well, die well

while a genocide away

Some would challenge this moral imperative to speak up, show up and stand up in education. They would want to remind us of the guidance on the balance of views and the need to maintain political impartiality. To this group of people I say, I hear you. I have been hearing almost no responses from education but this for nearly two years.

Here is the painful truth: There is no impartiality.

There is no impartiality when Gaza is being bombed by weapons manufactured in the UK, with the assistance of UK spying planes, and with the political cover of most UK politicians and mainstream media. There is no impartiality when the historical making of Gaza as a strip of land inhabited by refugees happened due to the British colonial rule in Palestine. There is no impartiality when the UK is partial to this iconic struggle for justice that has spanned across 77 years and counting. In the case of Palestine and Gaza, we need to be factual, in the absence of the possibility of ever being impartial. Factual is the word. (Badwan, 2025)

Here is another painful truth: Pedagogy is always political.

Following the footsteps of critical educators such as Paulo Friere (Freire, 1970), we learn that education is always political. I recently read a LinkedIn post from Phillip Proudfoot (2025) where he says ‘to insist that all lives have equal value is, and always has been, an act of disruption’. For everyone who cares about inclusion, diversity, equality, justice, tackling disadvantage, special needs, safeguarding and the future of humanity as a whole, your work is inherently political. Own the word. Don’t let the fear of using this word conceal the awful truth around the state of human societies.

Pedagogy is political. Indeed, ‘every political struggle is also a struggle over pedagogy, over who shapes the common sense of a society’ (Giroux, 2025). Pedagogy is a tool to govern, world, and shape the future. We stand on shaking and shaken grounds. We need urgent thinking to move forward with pedagogies of care.

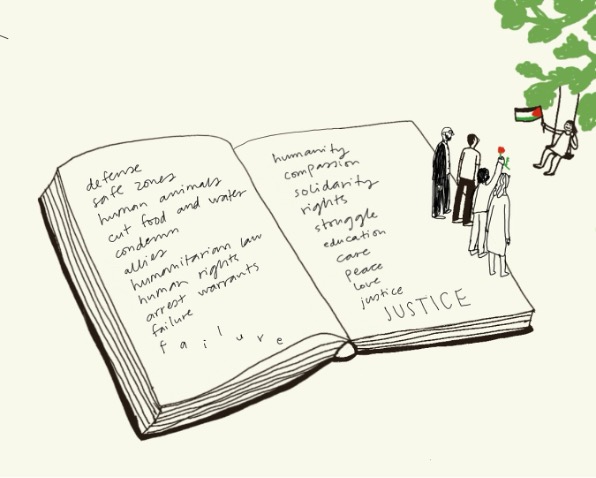

The choice is yours. I hope you stand on the right side of history. As well as on the right side of the book. See Illustration (1) by Anu Paajanen, below.

Many of us in this room are familiar with Judith Butler’s (2016) work on the notion of ‘grievability’ which raises serious questions on the selective allocation of grievability. Whose lives do we grieve? Who is just living? Who is having a life? Whose lives do we just dismiss as ‘unfortunate’ or ‘too complex to comment on’. To grief is to attend to the world and mourn what is taken, killed, bombed, and denied. To grieve is to feel the world’s broken-ness and to sit with life and death. To grieve is to stay alive. To teach life despite the rituals of attending to the dead, even as life becomes impossible.

I, not only, sit with grief. The pen name that I use when I sign my almost-daily poems for Gaza: Khawla in Grief. I also sit with failure and heartbreak.

I direct the critique of failure and heartbreak to education as a discipline and a profession. MY critique is short. It is wrapped in a poem called ‘What Remains?’

What remains

when education

remains silent,

when futures

are measured

in targets, not

in songs for humanity?

What remains

when Gaza

struggles to remain,

when atrocities

are streamed

and authorities

are revealed?

What remains

when worlds are lost

and lines are crossed?

What remains

when we are wounds,

with words killed

and values not lived?

Nothing remains-

except trying

(What remains, 27 June 2025)

I now speak in the spirit of trying, drawing on what I know from my discipline of applied linguistics and my profession as a teacher educator.

In concluding their powerful work, Linguistic Disobedience, Yulia Komska, Michelle Moyd and David Grambling (2019) ask: ‘what everyday antidotes are there to shock events, gaslighting, denial, deflection, and everything else that renews the daily prospect of losing one’s mind? What can help us regain our minds?’ In attempting a response, at the impossibility of a full response, I present to you three elements of what I call a pedagogy of care, as an antidote to help us find our minds, our words and our worlds.

I outline these three elements in a recent publication where I discuss a reparative praxis with Gaza. The following is reproduced from Badwan (2025):

1. Find Language: Develop Your Reparative Lexicon with Gaza

There can be no justice, nor reparation without language that breaks the silence on Gaza. Learn your language and find your voice. Engage with recent reports from credible sources such as Save the Children, Amnesty International, UNICEF, Oxfam, The Lemkin Institute for Genocide Prevention, Medical Aid for Palestinians, United Nations, among many others. These reports are anchored in precision, documentation, international humanitarian law and legal frameworks for genocide punishment and prevention. Remember, factual is the word.

2. Move forward with Wounds: Develop Pedagogies of Care

The choice is yours. You can insist on being in denial, refusing to open your eyes to the moral wounds of living in genocidal times. Alternatively, you can open your mind and your heart to the collective wounds of witnessing Gaza and the decimation of its children. I hope you choose the latter which will then require you to develop pedagogies of care through transforming classrooms into spaces for collective caring and healing. Arts, stories, poetry, music, drawing, dancing and creative practice are pedagogical tools to teach, learn, express and practise care. Through them we learn to live with the wounds of genocidal times, leaning into the pain and grief, rather than tapping out from whatever there is that connects humans together in a world of travelling bombs.

3. Feel Gaza Everywhere: Let Gaza be a Catalyst for Fairer Educational Presents and Futures

Reparative educational futures insist on the importance of metabolic literacies (Machado de Oliveira, 2021) that see all of us as connected together and nested within larger harmful capitalist structures. The unprecedented global entanglement in the Gaza crime scene is a living witness to how we are all glued to violent structures of oppression. How do we move on with this wounded and wounding reality in education?

There is no easy answer to this, but any attempt at an answer requires us to feel the pain of Gaza and to let it be a catalyst for fairer educational presents and futures. Through the lens of Gaza we need to ask the following:

- Whose voicesdo you teach and reproduce in education? Whose voices are silenced and pushed away or aside as ‘irrelevant’, or ‘political’? Who decides this? What role can you play?

- How are inclusion policiesdeveloped in your school? By whom? Who do they include? Who do they exclude as ‘irrelevant’, or ‘political’? Who decides this? What role can you play?

- Do you have a bereavement policyfor staff and children, with a support system that acknowledges ongoing trauma? Who is excluded and whose grief is seen as ‘irrelevant’, or ‘political’? Who decides this? What role can you play?

- What is your position in relation to solidarity with the oppressed, with those without rights, with those deemed not humans, not animals, and not even trees? Who decides this? What role can you play?

This list is incomplete. The message is:

Gaza is entangled with everything we say and do in education.

Gaza Matters

Without Gaza,

our scholarship loses its value

our education loses its meaning

our values lose their mooring

our world loses its order

our words lose their holding

And with Gaza

we can dare

to educate

tell of the harms and wounds

the ongoing attacks

on humanity and collective memory

Perhaps one day

Perhaps

We can find our ways

through the ruins

despite the ruins

Alison: Out of Ashlaa – The menace of hope

Before coming to our conclusions, I must first offer some reflections from my own research.

- The failures we speak of are, at root, cultural. This is where we must situate both our quest for understanding and our work for repair. Genocides always begin culturally before they become political. They are woven into the fabric of language and cultural ideas, which are then used in the education of hate, countered, or met with silence and void. ‘Evil’, as Arendt says, ‘comes from the failure to think’.

- Genocides are sanctioned or stopped by education as one of the key pillars, alongside political action. The media are critical in this regard, as is higher education and as are the religious and cultural institutions which can, when healthy, under SDG 16- be strong institutions for peace. They can also become strong institutions for violence, creating the conditions and the sanctioning and the silence, which is the failure to think. Just business as usual.

- Higher Education in particular is the training ground for cultural workers, artists and those who work with the strongest of symbolic systems we have as human beings – our powers of expression, especially in language.

- In Gaza, the institutions of culture – the universities, archives and libraries, and cultural centres – together with the journalists and public intellectuals – were the immediate targets. Scholasticide (Nabulsi 2009) is a vital constituent of genocide. Through the exceptional work of a handful of academics worldwide, and in response to the Gaza Emergency Call, a curriculum for Education in an Emergency, has been designed, developed and delivered. I refer here especially to the work of Al Masri, Fassetta and Imperiale which has seen Masters students educated; PhD Vivas successfully passed; I refer to the response from Applied Linguists to the request for teachers online, to the work of medical educators delivering teaching to those in the hospitals, drafted in as students, to treat the wounded, and learning alongside. Finding the language with which to keep educating.

- Higher Education worldwide is vital to both the prevention of genocide, and the rebuilding of higher education. Without it, nothing can be rebuilt. It is the first principle. Without cultural health in education there is no rebuilding. This must also be a cultural health sustained by intercultural, multilingual education. (Barakat, 2024).

- In Scotland one of the most beautiful examples, endorsed by the Cabinet Secretary in Scotland is in the work of the Welcoming Languages Project, led by Fassetta and Imperiale (Fassetta et al., 2023; Grazia Imperiale et al., 2023). Here teachers educators from Gaza worked with Arabic speaking refugee children and families in Scotland, to enable children to co-design a curriculum through which they would teach their primary school teachers and staff to speak ‘the words of comfort and care’. It was a source of joy, and care. It did the work of repair, dignity.

- Their project is an outworking of the New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy, which is underpinned by our research, and which sees education with Refugees as needing to be trauma-informed; restorative in nature; normal – the Right to be ordinary, as intercultural, multilingual and done in partnership. But more than this – it must destitute the violence, creating oases instead. In short, it works to ‘keep the peace’ and augment the peace we have.

- In our new Handbook for Integration with Refugees: Global Learnings from Scotland you can find many more such examples, not least the work done in, by, with and through communities in a whole society approach, commended by UNHCR High Commissioner in March 2025, when he visited Scotland . (Aldegheri, 2025).

- So, look to the non-funded, the voluntary, movement-led education: Community ESOL is so much more than ‘valuable skills’. It is food, friendship, bonds, legal advice, citizens advice, gardening, art, belonging. To many I have researched with, it is ‘family’. It is the place where we glimpse pedagogies out of ashlaa’. It is Edu – caring. And it needs the care of our mainstream education too. Many, many of you, I know, do this on top of your day jobs. (Aldegheri, 2025).

Such an education still finds a way of continuing and showing what Scarry speaks of in her work on ‘Thinking in an Emergency’ and on Beauty and being Just (Scarry, 2001, 2011):

People seem to wish there to be beauty even when their own self-interest is not served by it; or perhaps more accurately, people seem to intuit that their own self-interest is served by distant peoples’ having the benefit of beauty. (Scarry 2001)

It is why we learn from those who can show us when and where a comet might make its sweep across a sky.

Conclusions

In situations of ashlaa education often becomes palliative. It develops the art of Hospicing the education that has been, and the educational futures that were dreamed, and strives for a poetics from beyond the abyss that might acknowledge the failures and make room for the same qualities of courage, faith and a cheerfulness we have found in the children, students and colleagues who inspire our work.

From our examples of education undertaken under siege, in conflict and with, often led by refugees, we know the importance of restoring pedagogic normality. The learning that comes from education in emergencies, alongside what we have learned of restorative pedagogies in times of heartbreak shows us the vital import of pedagogies of care, pedagogies which care for words in a culture of lies ((McEntyre, 2009). We know that our work must also be palliative, as Khawla and I write in our article ‘hospicing Gaza’; that we are required to attend – as Vicktor Klemperer did during the Holocaust of the Second War, to the language being taught by the educational masquerade that is propaganda: “It is shocking that day after day naked acts of violence, breaches of the law, barbaric opinions, appear quite undisguised as official decree.” (Victor Klemperer, 1933).

We know there are dangers, as Rose says not all that plainly, in over remembering, or remembering to excess, what she calls ‘activity beyond activity’, and to a point where the horror cannot ever be resolved. In her studies of the work of Holocaust Education in Auschwitz (Rose, 1996) she shows how mourning became an ‘activity beyond activity’, never to be completed. From Holocaust Memorial Education to Remembering Srebrenica we may critically observe an unresolved need is to stay in an unknowable past of hell, of suffering, victimhood. Against Derrida’s ‘I mourn, therefore I am’, Rose instead insists that mourning must be completed and that the ‘work of mourning is the spiritual-political kingdom – the difficulty sustained, the transcendence of actual justice’.

Genocides succeed absolutely when mourning is not accomplished, in all senses of that word. If you are not grieving, not reaching for learning, language, arts, friends to care and care with and for, you are waiting for genocide to complete itself. There must be healing, truth and forgiveness and reconciliation. Mourning must be accomplished and learned too.

In times of failure and heartbreak the work of language education too must struggle. Language which fails as it tries to find words, which, as O’Tuama says in On Being can be guided by courtesy, poetics not precision, and when there are no precise words for the hell that has been endured (On Being).

Education of heartbreak and failure has to do the language work: work through the propaganda, the lies, the failed curricula for excellence, and ‘sticky knowledge’, the failed structures of abyss and fear and find ruderal repair, through languaging pedagogies of care, of preparing, serving, sharing, of naming the abyss and the wounds – accurately. It has to use and revise the terminology previous generations have carefully prepared for us. When this happens, as our research has found time and again we move through an education in hospicing into healing, repair, care and the beauty that persists, without risk of diminishment of suffering, or of allowing death to destitute us of love.

Lean in

You can lean in

towards the suffering,

or lean out.

It’s your choice.

You are the only one

making it.

It is all revealed.

You can recycle

empty propaganda

pretending your

superficial peace,

or you can lean in.

Cup your hands.

Make something of love

for the thirsty to drink

allowing yourself

with millions more

to be gripped

by the menace of hope.

Alison Phipps

[i] We are grateful to David Gramling for bringing the writing by Shaloub Kavorkian to the plenary lecture at UNESCO RIELA Spring School 2025 and strengthening our conceptual foundations.

References

Aldegheri, E., Dan, F., & Phipps, A. (2025). A Handbook of Integration with Refugees: Global Learnings from Scotland. Multilingual Matters.

Albanese, F. (2025). From economy of occupation to economy of genocide. Human Rights Council. Available from: https://www.un.org/unispal/document/a-hrc-59-23-from-economy-of-occupation-to-economy-of-genocide-report-special-rapporteur-francesca-albanese-palestine-2025/#content

Badwan, K. (2025). Reparative Praxis with Gaza: Living with Wounds in Education. Repair Ed: https://www.repair-ed.uk/reparative-praxis-with-gaza/

Badwan, K. (in press). Urgent reckoning in times of failure: Language with Gaza. Global Commons Review.

Badwan, K. (under review). What remains when schools remain silent on the genocide in Gaza? British Psychological Society.

Badwan, K. & Phipps, A. (2024). Keep Telling of Gaza. Sidhe Press. https://www.sidhe-press.eu/books/keep-telling-of-gaza/

Badwan, K. & Phipps, A. (2025). Hospicing Gaza (غزة): Stunned languaging as poetic cries for a heartbreaking scholarship. Language and Intercultural Communication, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/14708477.2024.2448104

Barakat, S. P. (2024). Gaza: Leadership and Reconstruction for the “Day After”.

Brueggemann, W. (1999). The Covenanted Self: Explorations in Law and Covenant. Fortress Press.

Butler, J. (2016). Frames of war: When is life grievable? Verso Books.

De Vogli, R., Montomoli, J., Abu-Sittah, G., & Pappé, I. (2025). Break the selective silence on the genocide in Gaza. The Lancet, 406(10504), 688–689. https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(25)01541-7/fulltext

Fanon, F. (1986). Black skin, white masks. Repr. London: Pluto Press.

Fassetta, G., Imperiale, M. G., Alshobaki, S., & Al-Masri, N. (2023). Welcoming Languages: teaching a ‘refugee language’ to school staff to enact the principle of integration as a two-way process. Language and Intercultural Communication, 23(6), 559–573. https://doi.org/10.1080/14708477.2023.2247386

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Continuum.

Freire, P. (2003). Pedagogia Da Esperança: Um reencontro com a Pedagogia do oprimido. Pax e Terra.

Freire, P. (2006). Pedagogia do Oprimido (Vol. 43rd). Paz e Terra.

Giroux, H. (2025). Death of Memory Is the Death of Democracy. LAProgressive. https://www.laprogressive.com/progressive-issues/death-of-memory

Glissant, É. (2009). Poetics of Relation. Nachdr. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Glissant, É. (2009). The Poetics of Relation. University of Michigan Press.

Grazia Imperiale, M., Fassetta, G., & Alshobaki, S. (2023). ‘I need to know what to say when children are crying’: a language needs analysis of Scottish primary educators learning Arabic. Language and Intercultural Communication, 23(4), 367–384. https://doi.org/10.1080/14708477.2023.2168010

Arendt, H. (1963). Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil. Viking Press.

Hammad, I. (2024). Recognising the stranger: On Palestine and narrative. Vintage.

Heidegger, M. (2007). Being and time. Malden (Mass.): Blackwell publ.

Jackson, P. (2011). What Is Education? University of Chicago Press.

Komska, Y., Moyd, M., & Grambling, D. (2019). Linguistic Disobedience. Palgrave.

Machado de Oliveira, V. (2021). Hospicing modernity: Facing humanity’s wrongs and the implications for social activism. North Atlantic Books.

Mbembe, A. (2003). Necropolitics. Public Culture, 15(1), 11–40. https://doi.org/10.1215/08992363-15-1-11

McEntyre, M. C. (2009). Caring for Words in a Culture of Lies. Eerdmans.

Phipps, A. & Saunders, L. (2009). The sound of violets: the ethnographic potency of poetry? Ethnography and Education, 4(3), 357–387. (NOT IN FILE)

Pring, R. (2001). Education as a Moral Practice. Journal of Moral Education, 30(2), 101–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057240120061360

Proudfoot, P. (2025). LinkedIn Post: https://www.linkedin.com/feed/update/urn:li:activity:7368600210127683584/?updateEntityUrn=urn%3Ali%3Afs_updateV2%3A%28urn%3Ali%3Aactivity%3A7368600210127683584%2CFEED_DETAIL%2CEMPTY%2CDEFAULT%2Cfalse%29

Rogers, P. (2025). Gaza bombing ‘equivalent to six Hiroshimas’ says Bradford world affairs expert. Available from: https://www.bradford.ac.uk/news/archive/2025/gaza-bombing-equivalent-to-six-hiroshimas-says-bradford-world-affairs-expert.php

Rose, G. (1996). Mourning becomes the Law. University of Cambridge Press.

Said, E. (1975). Beginnings: Intention and Method. Basic Books.

Scarry, E. (2001). On Beauty and Being Just. Duckbacks.

Scarry, E. (2011). Thinking in an Emergency. W.W Norton & Company.

Shalhoub-Kevorkian, N. (2024). Ashlaa’ and the Genocide in Gaza: Livability against Fragmented Flesh. Fieldsights.

Yohannes, H. T. (2024). Autobiographic reflections on loss, longing, and recovery. In: M. Bosworth, K. Franko, M. Lee, & R. Mehta, eds. Handbook on Border Criminology. Northampton: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Yohannes, H. T. (2026). The refugee abyss. Abingdon, Oxon; New York, NY: Routledge.

Yohannes, H. T., Yemane, T. H., & Wangari-Jones, P. (2024). Chapter 1: The Hostile Environment, Covid-19, and the Creation of Asylum Colonies in the UK. In: G. K. Bhambra, L. Mayblin, K. Medien, & M. Viveros, eds. The Sage handbook of global sociology. London; Thousand Oaks; New Delhi; Singapore: SAGE.

First published: 11 September 2025