Research visit to advance diagnosis of condition common in Sub-Saharan Africa

Published: 30 August 2022

Scottish scientists are teaming up with researchers from Zambia to find new ways to diagnose and treat a condition which affects millions in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Scottish scientists are teaming up with researchers from Zambia to find new ways to diagnose and treat a condition which affects millions in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Ms Kanekwa Zyambo, from the University of Zambia, is spending two weeks at the Scottish Universities Environmental Research Centre in East Kilbride to master new technology to help understand environmental enteropathy (EE).

EE is a disorder of the gut which scientists think plays an important role in malnutrition and stunted growth in children. It also reduces the effectiveness of oral vaccines.

EE is common in tropical low and middle income countries across Sub-Saharan Africa, South East Asia and Latin America. It contributes to around 150 million cases of childhood stunting around the world, a condition which is associated with impaired cognitive ability and reduced school and work performance.

The visit is part of an ongoing £2.9m UKRI Medical Research Council-funded collaboration between researchers at the University of Glasgow, the University of Zambia, Queen Mary University of London and Imperial College London.

The researchers are working to optimise a test for EE which can recognise how much gut damage there is by analysing samples of patients’ breath. Early diagnosis of gut damage could help doctors deliver treatment to prevent the advance of the condition, which is associated with chronic gut inflammation and in severe cases infection and death.

They have already developed a prototype breath test built around a process known as isotope ratio infrared spectrometry. It works by asking patients to swallow some table sugar which contains a little more of the stable isotope form of carbon than is normally consumed in everyday sugar.

For a couple of hours after ingesting the sugar, patients breathe into collection tubes. Then, a highly-specialised piece of equipment uses a laser to measure the isotopic composition of their breath, which shows how much sugar has been digested by the gut and released in breath as carbon dioxide.

The results will vary depending on the gut health of the patient. A healthy patient, whose intestine has digested the sugar normally, will have a distinctly different isotopic signature compared with a patient with EE, who display a reduced capacity to digest nutrients.

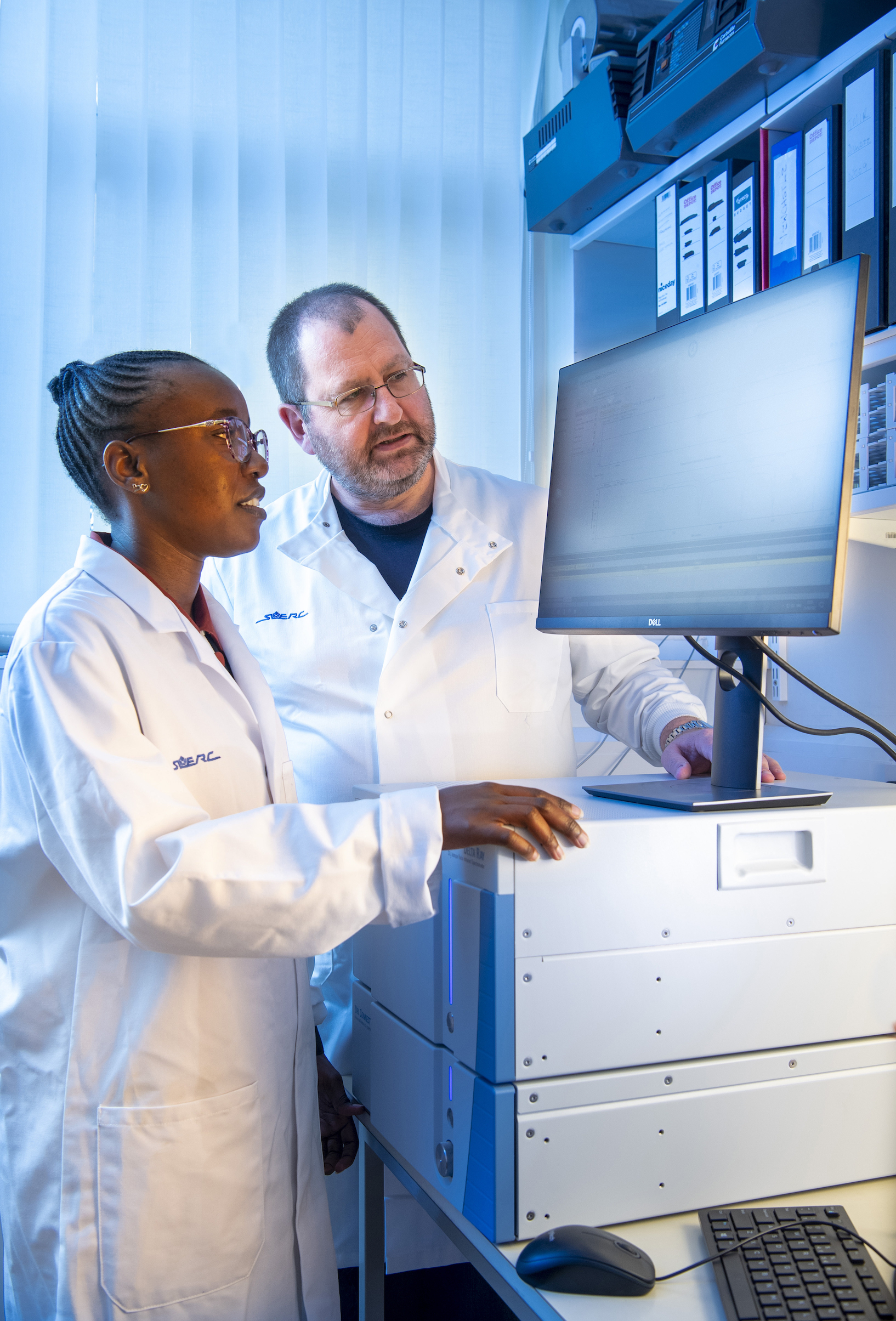

During the visit, Dr Douglas Morrison of SUERC is helping Ms Zyambo optimise the Thermofisher Delta Ray infrared spectrometer to deliver breath tests. Once the training is complete, Ms Zyambo will travel back to the University of Zambia’s teaching hospital to install the equipment and begin further trials of the breath test.

Ms Zyambo also visited Professor Christine Edwards at the University of Glasgow’s School of Medicine, Dentistry and Nursing to learn about a new way to assess the function of gut bacteria.

Scientists have shown that gut bacteria are different in children with EE-like gut abnormalities. This MRC project will assist transfer of this methodology from Glasgow to Zambia to enable deeper insight into the function of the microbiota of Zambian children.

Dr Morrison, of SUERC and the University of Glasgow, said: “Breath tests have significant potential to provide rapid diagnosis of gut related disease avoiding the need for invasive biopsy while saving patients the discomfort and inconvenience of providing blood, saliva or stool samples – a major advantage in a disorder like EE, where clinicians mostly look to treat children.

“We’ve run a number of small studies both here in Glasgow and in Zambia which demonstrate real potential for the breath tests we’ve developed to characterise EE. These results were recently published in the journal Frontiers in Medicine.

“I’m pleased that we will expand the scope of future studies in Zambia thanks to Ms Zyambo’s visit, and I’m hopeful that together we’ll be able to gain greater insight into EE and its role in stunting in the places where stunting prevalence is high.”

Ms Zyambo, of the University of Zambia’s Tropical Gastroenterology and Nutrition Group (TROPGAN), added: “I’m delighted to have been able to visit SUERC to learn about this new technology for delivering breath tests which will help us understand EE in our setting.

“I’m looking forward to returning to Zambia to continue this important work with my colleagues in the next stage of research, and advancing this collaboration between researchers in Africa and the UK.”

The Thermofisher Delta Ray infrared spectrometer will accompany Ms Zyambo back to Zambia at the start of next week, once her visit to SUERC is complete. The researchers expect new studies on the effectiveness of their breath tests to begin on-site before the end of the year.

First published: 30 August 2022

<< August