Holography history archives merge

Published: 15 November 2016

Two important archives are being merged to capture the history of holograms and their innovators.

Two important archives are being merged to capture the history of holograms and their innovators.

UofG's Professor Sean Johnston has donated a large research archive to an even larger collection at de Montfort University, Leicester, gathered and managed by Professor Martin Richardson.

Their aim is to preserve the history of the still-mysterious art of holography and to inspire continuing innovation.

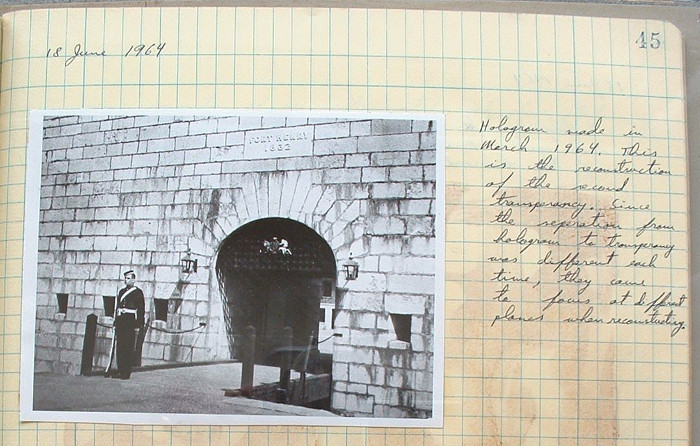

The materials include correspondence and interviews with dozens of seminal figures in the field such as Emmett Leith at the University of Michigan and Yuri Denisyuk of the Vavilov Institute in St Petersburg, Russia. The collection also contains reminiscences, photographs, exhibition catalogues, unpublished documents and holograms from holographic artists, engineers, scientists, business people, enthusiasts and collectors.

Professor Richardson’s archive, which he has been amassing throughout his varied career, carefully preserves art and commercial holograms from pioneering businesses that have come and gone.

Based at UofG's Crichton Campus in Dumfries, Professor Johnston’s archives were built up over the past 15 years during his historical studies of holograms, their creators and their audiences. His research has led to publications and presentations around the world, and culminated in two books published by Oxford University Press: Holographic Visions: A History of New Science (2006) and Holograms: A Cultural History (2016). Now, as his research extends in new directions, Professor Johnston wants to make the collection available to other scholars and creators.

Rare and intriguing

Since holograms were first conceived by Dennis Gabor in 1947, there have been at least 20,000 contributors to the field, 7,000 patents, 1,000 books and countless commercial products. Holograms have evolved to intrigue audiences over three generations, although most ‘holograms’ viewed today are in fact inferior technologies based on Victorian stage tricks. Viewing genuine holograms remains a privileged and memorable experience.

Collections that document the history of the subject are far rarer. Most are still in the hands of their creators, many of them now retired. National museums and large companies, even in the countries that have contributed to holographic innovation, do not have sustained collecting policies for the subject. Acquiring, documenting and protecting the materials can be expensive for institutions.

As a result, the history of the subject is threatened with disappearance.

“I’ve been approached by holographers in industry, engineering and art seeking a permanent home for their life’s work” said Professor Johnston, “and I’ve recommended building a critical mass by merging collections.”

To encourage such moves, Professors Johnston and Richardson aim to unite their diverse treasures to preserve the broad history of holography.

More information

- Professor Sean F Johnston

- Holography and Three-Dimensional Imaging at de Montfont University

First published: 15 November 2016

<< November