Dragons of Silk and Stone

This virtual exhibition introduces the power of dragon symbolism through two Chinese silk robes and jade dress accessories from The Hunterian collection. It has been curated by postgraduate History of Art students from the University of Glasgow. A Chinese language version of the exhibition is also available.

Introduction

This exhibition is built around two silk robes and jade dress accessories from The Hunterian collection. Both silk robes are profusely decorated with dragons, which also feature on the belt hooks and belt plaques. Since the dragon is such an omnipresent mythical animal in Chinese culture, the exhibition introduces dragon symbolism more broadly and beyond China.

Though the two robes are covered with five-clawed dragons which were reserved for the rulers in imperial China, it is likely that they are in fact representations of imperial robes made to be worn by actors of the Chinese opera.

Dressing in Dragons at the Imperial Court

Imperial robes in China communicated specific messages of power in the Qing dynasty (1644-1912). The Manchus introduced a version of the robe with long sleeves shaped like horse hooves. This was to celebrate the origins of the Manchus as horse riders and the role of horses in their conquest of China.

Silk woven in the kesi method and ornamented with animal and cloud motifs was used for both summer and winter imperial robes. Elaborate sumptuary laws regulated what robes could be worn by the imperial family and the officials. For example, the dragon is one of the most prestigious animals throughout Chinese history.

On robes for the imperial family it appears with five claws (longbao), while officials' robes have only four claws (mangbao). The golden yellow (jinhuang) robes were worn by the emperor on special occasions.

See an example of a Qing dynasty imperial court robe from The Palace Museum, Beijing.

Court Dress Accessories

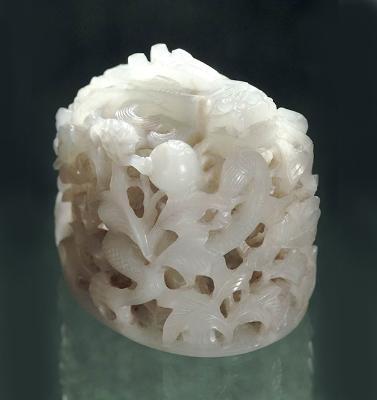

Jade is a highly prized stone in China, symbolising purity and excellence. The dense stone, ranging in colour from milky white to dark green, was extremely hard to carve and decorate. It was used to produce a range of courtly accessories, primarily during the Ming and Qing dynasties.

Jade belts were an essential part of courtly garments and their use extends throughout the history of China. During the Qing dynasty, they were made of leather and had sewn plaques and buckles of jade, as well as other luxurious materials, according to the rank of the wearer. In the images below we can see a clasp, hooks and plaques belonging to those belts, many of which have dragons carved on them.

It is thought that masters of Daoism, a Chinese philosophy, would wear jade topknot ornaments in their hair with the pin running front to back and that scholars would wear them from side to side, creating a topknot style. They were also worn by emperors and members of the courtly elite to evoke these aspirations. They were often constructed from other luxurious materials such as gold, amber and tortoiseshell.

According to the regulations of the Qing court, only the emperor, empress dowager, and empress (the chief wife of an emperor) were permitted to wear adornments with Eastern pearls during certain ceremonies at the palace.

This Court necklace is made from one hundred and eight beads of jadeite and semi-precious stones.

Hat designs vary according to the wearer, made with exact specifications following imperial rules about what different ranks could wear. The top finial bead shows the importance of how the owner indicated his rank among other officials.

Actors in Dragon Robes

It has been suggested that the robes in The Hunterian collection may not be formal imperial court robes. It is more likely that these are theatrical robes purchased by individuals on the market. Chinese opera costumes are similar to formal robes, reusing features and colours from court dressing and emphasising them, to convey characters’ identities and status to the spectators from a distance.

Chinese opera is a performing art form blending acting, music, recitation and martial arts. It is a flamboyant performance designed to entertain and to inform about history and society. Developed at the Qing imperial court, it remains a popular practice today.

Beijing opera, the most widespread form, has been recognised as intangible cultural heritage in 2010.

View a robe from the Palace Museum Music and Opera collection.

Collecting Jade: Ina J Smillie

As a material, jade was not particularly popular on the European market until a surge in its availability after the sacking of the Summer Palace in Beijing by British and French soldiers in 1861. Even after this point, it was not particularly revered and was more affordable. This perhaps made it more suitable as an object for Ina Smillie to collect - intriguing and intricate pieces, but small enough to house in an individual’s home.

As the popularity of jade increased, more private collectors began to display jade in their homes. Although many of these items have a distinct purpose, such as the belt buckle and the incense burner, European collectors of jade would rarely use the item as it was intended. Instead, the object would be privately displayed and regarded as a thing of beauty and elegance. Although often displayed in a private setting, its influence was still far-reaching.

From the Art Deco movement (which appreciated the jade material for its colour and for its symbolism) to jewellers such as Cartier, many were inspired by jade. While the provenance of objects collected and the intention of the collector remain uncertain, this collection falls well within the common appreciation and fascination of Europeans for jade.

Ina Smillie’s jade collection is on display in the Hunterian Museum and is available for viewing online. Her successful violin studio was on Great Western Road in Glasgow, not far from where her collection is now housed.

View a jade vase, cover and stand from the V&A collection.

Dragons and Related Symbolism in China

These videos present how Chinese dragons differ from the Western. It is a symbol of imperial dignity and traditional mascot. It has nine sons, each of them appears on different occasions and objects according to their different symbolic meanings. And the Chinese people believe in the concept of the cycle of life and death, people can ride a dragon to heaven. Life would eternally continue in another dimension.

YouTube videos on Chinese Dragons

Dragons: A Chinese symbol of power (Hello China #24)

Chinese dragon's nine sons (referring to different kinds of 'dragons’ which are not long 龍 dragons)

Every Treasure Tells a Story: Silk Painting Depicting a Man Riding a Dragon

Global Dragons

The Chinese dragon has been a symbol for power, strength and good luck for the people of China for centuries. Global appropriation of dragon iconography has since produced alternative depictions of the dragon.

One of the more widely recognised is St George fighting and slaying the dragon. This story has been represented in both Eastern and Western cultures through artworks and literature and has even infiltrated Western economies and society on coins and stamps (as seen in the images below and website links).

In contrast to the powerful symbol of strength that the dragon represents in Chinese culture and heritage, this scene depicts the dragon as the enemy of the people - an evil force to be defeated. St George is celebrated for heroism and is the patron saint for various countries including England and Georgia.

View an example of a dragon costume worn for the Chinese Dragon Dance.

Sources

Publications

Bjaaland Welch, Patricia. Chinese Art: A Guide to Motifs and Visual Imagery. North Clarendon, VT: Tuttle Publications, 2008.

Bonds, Alexandra. Beijing Opera Costumes: The Visual Communication of Character and Culture. New York: Routledge, 2019.

Cammann, Schuyler. “Costume in China, 1644 to 1912.” Philadelphia Museum of Art Bulletin 75:326 (1979): 2-19.

Cammann, Schuyler. “The Making of Dragon Robes.” T'oung pao 40:1 (1951): 297-321.

Fang, Gu and Li Hongjuan. Chinese Jade: The Spiritual and Cultural Significance of Jade in China. New York: Better Link Press, 2013.

Mailey, Jean. The Manchu Dragon: Costumes of the Ch'ing Dynasty, 1644-1912. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, December 16, 1980 – August 30, 1981.

Online Sources

Denver Art Museum. (2011). Summer Official's Hat. [Accessed 17 Feb 2021].

So, J.F. (2019). Early Chinese Jades in the Harvard Art Museums. [Accessed 17 Feb. 2021].

The British Museum. (2021). Hair-ornament [Accessed 17 Feb. 2021].

The Palace Museum. (no date). Pearl Court Necklace. [Accessed 17 Feb.2021].

Acknowledgements

This exhibition has been planned and organised by students of two History of Art postgraduate courses (Object Biography and Collecting and Display): Ioanna Arvaniti, Leigh Barker, Molly Baro, Louise Burns, Najiba Choudhury, Suzana Danilovic, Debra Davis, Clémence Dufour, Matilda Eriksson, Rebecca Fielding, Jing Guo, Sam Harley, Belén Hernáez Martin, Charlotte Labre, Weiru Lu, Yifan Qiu, Miyuki Sakai, Charlotte Swindell. The courses were led by Dr Minna Törmä, convenor of the MSc Collecting and Provenance in an International Context programme.

Embroidered silk 'dragon robe'

Embroidered silk 'dragon robe'  Embroidered silk 'dragon robe'

Embroidered silk 'dragon robe'  Embroidered silk 'dragon robe'

Embroidered silk 'dragon robe'  Embroidered silk 'dragon robe'

Embroidered silk 'dragon robe'  Jade belt-fitting

Jade belt-fitting Jade belt-fitting

Jade belt-fitting Jade plaque

Jade plaque Jade plaque

Jade plaque Jade belt-fitting

Jade belt-fitting Jade belt-fitting

Jade belt-fitting Jade belt-fitting

Jade belt-fitting Jade topknot

Jade topknot Porcelain plate with cobalt blue underglaze

Porcelain plate with cobalt blue underglaze Porcelain plate with cobalt blue underglaze

Porcelain plate with cobalt blue underglaze Ceramic plate produced by J & M P B & Co Ld Bell's Pottery

Ceramic plate produced by J & M P B & Co Ld Bell's Pottery Enea Vico

Enea Vico Gold half sovereign coin

Gold half sovereign coin