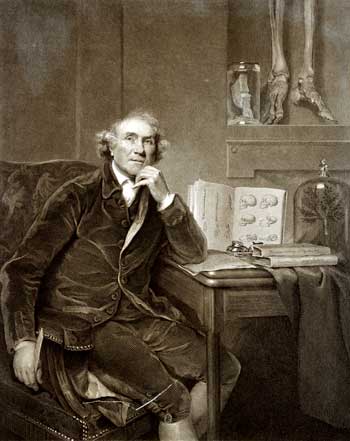

Dr William Hunter

Hunterian founder, Dr William Hunter, was a physician and teacher of anatomy. He used his wealth to build up the vast private collection which is the cornerstone of The Hunterian collections today. His bequest to the University of Glasgow in 1783 also provided money to build a new museum to house the collections.

Introduction

William Hunter was born at Long Calderwood, East Kilbride in 1718. Hunter’s father was a retired grain merchant from Glasgow and although the family was not poor, their income was small. His mother, Agnes Paul, was the daughter of a Glasgow magistrate. She was well educated and ensured that her children shared her taste for theatre, literature and the arts.

William Hunter was born at Long Calderwood, East Kilbride in 1718. Hunter’s father was a retired grain merchant from Glasgow and although the family was not poor, their income was small. His mother, Agnes Paul, was the daughter of a Glasgow magistrate. She was well educated and ensured that her children shared her taste for theatre, literature and the arts.

John and Agnes Hunter had ten children, but the family was affected by tuberculosis and ill health. William was their seventh child and only he, James, John, and their sister Dorothea survived into adulthood.

In 1731, at the age of 13, William Hunter enrolled at the University of Glasgow to study for a Master of Arts degree, which would lead him into a career in the church. During his four years at the University, William was taught by important figures in the Scottish Enlightenment. These included Alexander Dunlop, John Loudon, and the renowned Francis Hutcheson.

He also made lifelong friends among his fellow students, particularly the Foulis brothers, who became printers of the leading Enlightenment texts, and Tobias Smollet, the famous 18th century novelist.

William left the University of Glasgow at 19 without a degree but was later awarded a Doctor of Medicine in 1750.

Frances Hutcheson

Frances Hutcheson was the Professor of Moral Philosophy when William Hunter was a student at the University of Glasgow. Hutcheson was one who “awakened in the students a taste for literature, fine arts and everything that is ornamental and useful in human life, and spread such an ardour for knowledge and such a spirit of enquiry everywhere around him”. His philosophy had a major impact on William Hunter, helping him realise that he was no longer suited for a career in the church.

John Hunter

John Hunter

John was the youngest son of the Hunter family. His character was very different from his older brother, William. John was not a natural student. He preferred nature to books, but like his brother, he learned most of all from observation and experience.

When he was 20 years old, John followed his brother to London and became an assistant in William’s anatomy school. He quickly gained the reputation as an excellent anatomist and surgeon. As John’s fame grew, tensions between the brothers increased. John was not mentioned in William’s will.

Though their relationship was strained they did still share a love of collecting. John’s collections are now housed at the Royal College of Surgeons of England.

The Baillie Family

Much of what we know of William’s character has come from letters that were exchanged between him and the Baillie family.

William’s sister, Dorothea, married a family friend, the Reverend James Baillie, whose unexpected death led William to step in and support the family. He oversaw the education of his nephew, Matthew, who worked as an assistant in his anatomy school. Matthew went on to become a celebrated physician in his own right, and was appointed Physician Extraordinary to King George III.

On his death, William left the majority of his property to Matthew and the rest of the Baillie family.

Images: Allan's Ramsay's portrait of William Hunter.

Engraving of John Hunter by William Sharp, 1788, after a portrait by Sir Joshua Reynolds.

Medical Education

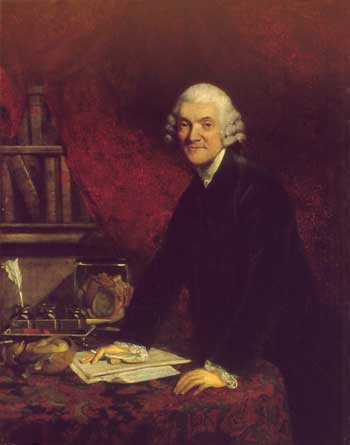

William Cullen

William Cullen

William Cullen, the famous chemist and physician, was born in Hamilton on the 15th April 1710. He matriculated into the University of Glasgow in 1726 and was also a student at Edinburgh University between1734 and 1736. He subsequently established a practice in Hamilton and acquired an MD from the University of Glasgow in 1740.

In 1751 he was elected Professor of Medicine at the University of Glasgow. Four years later he was installed as joint Professor of Chemistry at Edinburgh University, where he continued to teach until 1789. Ill health forced him to resign his chair shortly before his death in 1790.

The surviving correspondence between William Hunter and Cullen demonstrates a lifelong and affectionate friendship. Of all those closest to Hunter it was Cullen whom he considered that he ‘owed most and loved most of all men in the world’.

Edinburgh

Apart from London and Glasgow, William Hunter also maintained close links with the city of Edinburgh. He was a student at Edinburgh University between 1738 and the autumn of 1740. He attended the anatomy lectures of Professor Alexander Monro and also studied chemistry, medicine and materia medica (drugs). This comprehensive medical education provided Hunter with the foundations from which he was able to advance his own future research.

During a brief visit to Scotland in 1750, in recognition of his achievements in anatomy and of his connections with Edinburgh, he was formally made a Burgess and Guild Brother of the City.

London

London

William Hunter travelled to London in 1740 to begin studies in midwifery as the pupil of Dr. William Smellie, one of the leading figures in midwifery in the 18th century and a close friend of William Cullen. This association was to last less than a year as Hunter was also introduced to the eminent physician and anatomist Dr. James Douglas.

William became Douglas’s anatomy assistant and tutor to his son. He was also given accommodation in the Douglas household. James Douglas died in 1742. On his deathbed he insisted that his family promise to send William to Paris to study anatomy and surgery. Undoubtedly the support James Douglas gave William Hunter during his early days in London greatly helped to establish his career.

London Courses

Determined to make the most of his time in London, Hunter enrolled for two complementary evening courses on Natural Philosophy and Anatomy.

John Theophilus Desaguliers, Hunter’s Natural Philosophy professor, had worked as laboratory assistant to Sir Isaac Newton. He was very popular with students and members of the fashionable set. His lectures often included practical experiments. He was considered one of the best teachers of his time.

Frank Nicholls, his professor of Anatomy, was also among the best teachers in his field, as well as an expert in antiquities and art.

Paris and Leiden

In 18th century Britain, most anatomists who became well known had studied in Europe’s main medical centres, Paris and Leiden. Bodies were more readily available there for dissection. Hunter, keen to follow, first studied in Paris in 1743. He followed the best available courses on anatomy and surgery, and was at last able to dissect a whole body for the first time.

In 1748, planning to open a school of anatomy in London, he decided to refresh his knowledge of continental teaching practices. First going to Leiden in Holland, he met some of his heroes, such as the great Dutch anatomist Albinus, and visited important medical collections. In Paris, Hunter renewed old acquaintances and studied the latest developments in his field.

Images: Portrait of William Cullen.

Portrait of William Smellie.

Life in London

The Hunter Family in London

Having established himself in his “darling London”, William Hunter was able to support other members of his family who came to the city. His brother James stayed with him in the Douglas household, until having to return to Scotland in 1743 due to ill health. By 1748 his brother John had also travelled south to stay with William, who set about turning him into an anatomist.

His sister Dorothea stayed with him for a short while in 1757 before her marriage to James Baillie. He was also close enough to offer support and financial assistance to her son, Matthew Baillie, during his time at Oxford University.

Glasgow Friends

Glasgow Friends

William Hunter made many life-long friends during his time at university. Among those who remained in Glasgow were Robert (1707-1776) and Andrew (1712-1775) Foulis, who became book sellers and publishers and founded the Foulis Academy of Fine Arts within the University.

Tobias Smollett (1721-1771) met Hunter at university and, like him, went to London to seek his fortune. This famous 18th century novelist and critical essayist knew Hunter well.

Born in Lanarkshire, William Smellie (1697-1763) became a member of the Faculty of Physicians and Surgeons of Glasgow in 1733. He also moved to London where he became renowned for transforming midwifery. Hunter stayed with Smellie in London in 1740.

William Cullen (1710-1790) was one of Hunter’s oldest and dearest friends and his influence on him cannot be overestimated. Cullen was at the forefront of medical teaching and practice in Edinburgh and Glasgow. It was Cullen who encouraged Hunter to stay in London as assistant to Dr James Douglas, stimulating his career in man-midwifery.

Edinburgh Friends

William Hunter also formed several friendships during his stay in Edinburgh from 1738 to 1740. Allan Ramsay (1713-1784), Scotland’s leading painter was one. The engraver Robert Strange (1725-1792) was also a friend. Hunter interceded in a dispute between Ramsay and Strange and though they never reconciled their differences, each continued their friendships with him.

Robert Mylne (1733-1811), born in Edinburgh, was a leading architect of the early Neo-classical style in Britain. He was chosen by Hunter to design his house in Great Windmill Street. Like Hunter, he kept up his connections with his native country

Dr James Douglas (1675-1742) was born near Edinburgh, and graduated MA at Edinburgh University in 1694 and MD at Rheims in 1699. He had a highly successful practice in London as a man-midwife and anatomist and was also an avid collector of the works of Homer. Hunter joined Douglas in 1741 to become his assistant and he introduced Hunter to Dr Mead and the Royal Society.

Early Medical Circles

Early Medical Circles

In 1741, William moved into Dr James Douglas’s household to work as his anatomy assistant and tutor to his son. This opportunity catapulted William into the whirl of London’s intellectual social scene.

Chief amongst the men that Douglas introduced him to was Dr. Richard Mead, a ‘prince amongst physicians’. Mead was a Royal Physician and founder of the Foundling Hospital. His dining club attracted some of the finest minds that London society had to offer. William mixed with the leading surgeons William Cheselden and William Cowper. Mead’s table was not restricted to medical men; William encountered Alexander Pope, the famous poet and Allan Ramsay, the celebrated portrait painter at these gatherings. The opportunity to mix with the men who were leading the English Enlightenment gave William the chance to use his excellent networking skills to climb the social and professional ladder.

Eminent Friends

William Hunter’s status is aptly demonstrated by the circle of eminent friends and associates that he kept. Lifelong friendships with the painter, Allan Ramsay, the writer, Tobias Smollett, and the engraver, William Strange, were forged during his time as a student at both Glasgow and Edinburgh University. As a member of the Royal Society he was acquainted with men such as Benjamin Franklin and Sir John Pringle. Likewise his position at the Royal Academy of Arts brought him into contact with Sir Joshua Reynolds. He also commissioned three paintings by George Stubbs. At the height of the Scottish Enlightenment, Hunter corresponded with Adam Smith, David Hume and Joseph Black. Hunter was also a friend of the author, Samuel Johnson and the explorer, James “Abyssinian” Bruce.

Hunter’s Houses

1 Great Piazza, Covent Garden, 1749-1755

Hunter’s first home was a spacious town house that offered ample accommodation for him and his brother John, and for his anatomy school. At that time Covent Garden was a vibrant place of theatres, coffee houses, shops, and taverns. It was cheap enough yet easily accessible to students and patients.

49 Jermyn Street, 1755-1767

49 Jermyn Street, 1755-1767

Hunter became so successful that in 1755, he felt the need to move to a smarter area, leaving John in charge of the Anatomy School. Jermyn Street, brought him closer to his increasingly fashionable private clientele, whilst still being close to his school.

16 Great Windmill Street, 1767-1783

By 1767, Hunter had become a serious collector, and was running out of space in Jermyn Street. His last home was a large town house with substantial outbuildings. It incorporated, under one roof, his living quarters, museum and school of anatomy.

Clubs and Coffee Houses

Hunter shared his contemporaries’ enthusiasm for clubs, coffee houses and taverns. There, art and science would often overlap, contacts would be made and alliances formed. Hunter’s favourite clubs and coffee houses were also visited by other Scots. He would arrive after his lectures had finished, at around 9 pm, and relax with fellow countrymen and friends over a glass of claret. His favourite toast was ‘May no English Nobleman venture out of the World without a Scottish Physician, as I am sure there are none who venture in’.

Images: Portrait of Andrew Foulis, c. 1755.

Richard Houston's portrait of Dr Richard Mead, 1757.

Façade of William Hunter’s house at 16 Great Windmill Street, London. (Wellcome Photo Library, London).

Work and Achievements

Remarkable Teacher

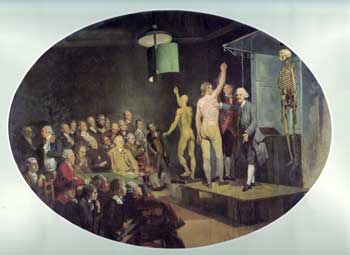

It is a mark of Hunter as a teacher that when he considered giving up lecturing, his students petitioned him not to. Their persistence encouraged him to seek premises large enough to contain London’s first private school of anatomy. Great Windmill Street included research and preparation rooms, but its biggest draw for students from all over the world was the focus Hunter placed on dissection.

“A man may do infinitely more good to the public, by teaching his art, than by practising it.” William Hunter

The unique combination of William Hunter’s excellent communication skills, the facilities he provided that encouraged the communication of ideas, and the emphasis on dissection, led Great Windmill Street to become London’s first scientific centre for medical teaching and research.

Famous Anatomist

British 18th century medicine was full of superstition and guesswork. Many medical practitioners were unqualified, and anatomical research was limited. They performed cures that had little or no proven success.

William Hunter applied a more enlightened and scientific attitude to his profession. At the centre of William’s work was the importance of dissection, a principle he had learnt whilst studying on the continent.

Using this approach, the advances he made in medical knowledge, particularly in the lymphatic system and the uterus, put him at the forefront of contemporary medicine. However, his greatest skill was his ability to share the knowledge he had gained. People flocked to his public lectures, including the economist Adam Smith and the acclaimed author and surgeon Tobias Smollett.

William had a flair for showmanship but his emphasis on the advancement of knowledge always ensured that his public dissections were more than mere public spectacle.

Infamous Anatomist

Infamous Anatomist

William Hunter argued that dissection was crucial to teaching anatomy. However, controversy arose over the question of where exactly corpses had been acquired. Grave robbing was a criminal offence, but that failed to dissuade those operating in such a lucrative trade. Although Hunter tried to be discreet in this matter he was unable to avoid attracting attention. One local newspaper reported on the high number of bodies that Hunter had delivered to his residence at Great Windmill Street and also that the remains were disposed of down a well in his garden – a practice that, on several occasions, had led to angry mobs demonstrating outside his house. He was also depicted in a cartoon in which he is seen hastily abandoning a woman’s body on sighting an approaching night watchman.

Acclaimed Author

William Hunter was a prolific and acclaimed writer. He published Medical Commentaries in 1762 and was also a regular contributor to Journals such as Medical Observations and Inquiries and Philosophical Transactions. His most famous work was The Anatomy of the Human Gravid Uterus in 1774.

He tended to focus on medical subjects but occasionally diverted his attention to more obscure subjects, such as his Account of the Nyl-ghau. Hunter also catalogued much of his own collection, including his extensive library, his anatomical preparations and his minerals. He was keen to support other authors, and his varied collections were widely used as the basis for numerous publications.

Obstetrician to Celebrities

Obstetrician to Celebrities

In 1762, William Hunter was appointed Physician Extraordinary to Queen Charlotte, attending all her pregnancies until 1783. This appointment enhanced his reputation.

In 1774, the Earl of Sandwich (1718-1792) wrote to Hunter thanking him for attending to his mistress, Martha Ray (1742-1779). Ray, an accomplished singer and musician, was a controversial figure and died in 1779, the tragic victim of murder by her lover, James Hackman.

Royal Physician

Early in his career, Hunter specialised in obstetrics and his reputation amongst London’s upper classes brought him to the attention of the Royal Family.

In 1762, he was asked to attend the birth of the future George IV. In keeping with the practice of the time, Hunter was not actually present at the birth of Prince George. A midwife tended to the Queen. He did not actually see the mother or child for an hour and a half after the birth.

William Hunter was appointed Physician Extraordinary to Queen Charlotte in 1764 and supervised the delivery of her fourteen other children.

Female Patients

William Hunter’s female patients rank among the most powerful and influential in British 18th century society. The Countess of Hertford, who was a Lady to the Bedchamber of Queen Charlotte from 1768 to 1782, was a close friend of Hunter. Through him she maintained links with fashionable society in London while she was based in Paris. Their relationship was such that in 1765, she asked Hunter to source some wallpaper from a maker in London.

Founding Academician

Founding Academician

Established to promote the art of design, the Royal Academy was founded on 10th December 1768. Joshua Reynolds was its first President and William Hunter was the first Professor of Anatomy. This appointment allowed him to indulge in two of his great passions, anatomy and art.

As Professor of Anatomy, he had to deliver at least six public lectures on anatomy. His first series of lectures focussed purely on anatomy, but in later lectures he covered the subject of the artist’s role in relation to Nature.

He believed that accuracy was crucial when depicting nature, as anything less would not be able to compete with the beauty of nature itself.

Recognition

William Hunter played a prominent role in the most prestigious cultural and scientific institutions of the 18th century, both in Britain and abroad. His image appears in two of the most significant works of art carried out to commemorate these organisations. Hunter appears in Zoffany’s painting, Life Class at the Royal Academy (1771-1772). He also appears in James Barry’s Distribution of the Premiums by the Royal Society of Arts and Manufactures (1777-1783).

Images: William Hunter lecturing at the Royal Academy of Arts; oil painting by Johann Zoffany, c. 1772. (Royal College of Physicians of London).

Portrait of Queen Charlotte by Thomas Burke, 1772.

Sir Joshua Reynold's posthumous portrait of William Hunter, c. 1787.

More

Character

Character

Hunter was careful by nature and led a simple lifestyle. He ate modestly, occasionally dining with some of his closest friends and pupils. However, his own brother John referred to him as a “miser”, whilst Dr Manning described him as “an ill-natured waspish creature”. James Boswell recalled how, “He spoke so tediously and so insipidly, that my mind was in such uneasiness as the lungs are when in want of air”. Hunter himself was acutely aware of both sides to his popularity, describing himself in a letter to William Cullen “as constant in my friendship as some others will find me implacable in resentment and determined in contempt”.

Money

William Hunter became an extremely wealthy man over his lifetime. Although not as rich as some of his aristocratic collector friends, Hunter’s spending was still significant and his collection was estimated to have cost him over £100,000 (£9,500,000 in today’s money). Unlike other collectors forced to sell objects because of personal debts, Hunter did not over speculate, ensuring his collection remained intact for future generations.

Interests

Hunter’s sister, Dorothea, talked of her brother as a man “indefatigable in making himself master of anything he wished to know”. As his collections extended, Hunter’s curiosity led him to take an interest in a wide range of subjects, touching on ancient civilisations, art, foreign cultures, and natural sciences. For example, fascinated by other cultures, he collected accounts of early travellers such as Marco Polo, and could not resist acquiring artefacts from the most recent voyage of discovery, that of Captain Cook to the South Pacific.

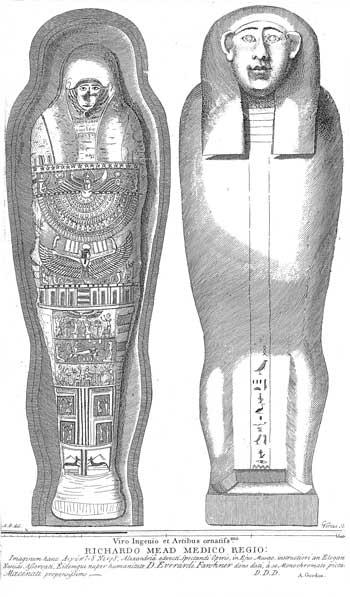

Other particular interests included Egyptian mummies, fossils from extinct species, pamphlets and other material related to the early history of America, the iconography of Dr William Harvey, who had discovered blood circulation in the 17th century, and the history of early printed books, on which he left an unpublished manuscript.

Mummies

Mummies

William Hunter bought an Egyptian mummy at the sale of Richard Mead’s collection in 1755. By studying it he hoped to find out more about the process of embalming, to compare the mummy with accounts of preparations in ancient texts, and to see how well the body had been preserved.

Hunter put his knowledge of the subject to practical use, when in 1775 he embalmed the dead wife of his eccentric dentist, Martin van Butchell. With the operation completed, the body was dressed, placed in a glass case and displayed in van Butchell’s living room. It survived in the museum of the Royal College of Surgeons until it was destroyed by bombing during the Second World War.

Exotic Animals

William Hunter made significant, but less well-known, contributions to the study of animals. Like many intellectuals of the time, his interest in zoology focussed on the debate on evolution and extinction, and the possibility of farming animals in Britain, like the Nilgai (a type of antelope).

There is no evidence that William kept exotic animals himself, but he collected, or was given, skins and skeletons for his museum. These included a kangaroo skin from one of Captain Cook’s expeditions and elephant tusks presented to him by Queen Charlotte.

Hunter commissioned the painter George Stubbs to paint exotic animals to help him with his studies into evolution and extinction. Stubbs shared Hunter’s passion for anatomy, so his paintings are scientifically accurate.

Extinction

The Mastodon was the first large animal to be declared extinct. The concept of an extinct animal was difficult for many to believe in the 18th century. It was thought that animals extinct in one place would turn up alive in an unexplored region of the world. William Hunter wrote a scientific article on the North American Mastodon which he concluded was an extinct carnivorous elephant. He had been able to obtain a couple of teeth for his collection and examined material in other collections. Although the Mastodon is now thought to be herbivorous, the article was a significant contribution to the debate on extinction.

Images: The Nilgai by George Stubbs, 1769.

An Egyptian mummy purchased from Dr Mead’s estate. (Reproduced from Alexander Gordon, An Essay towards explaining the ancient Figures on the Egyptian Mummy in the Museum of Dr. Mead, 1737, pl. xiii; courtesy of the National Library of Scotland).

Legacy

“I have a great inclination to do something considerable at Glasgow.” William Hunter

Hunter’s legacy was not only his medical advances but also his collection. In 1807 the University of Glasgow came into its inheritance. The collection was then, and is now, the core of Scotland’s oldest public museum.

Hunter suffered from rheumatism, gout, and kidney stones for a number of years. By 1783 his health was deteriorating. In March, still recovering from an attack of gout, he collapsed during one of his anatomy lectures. He died on the 30th March and was buried on the 6th April in the Rector’s vault at St. James’s Church, Piccadilly (destroyed during an air-raid in 1940).

By the terms of his Will (written in 1781) he left possession of his Museum and Library at Great Windmill Street to the Principal and Faculty of the College of Glasgow and a sum of £8,000 (nearly £1.2 million today) to build a museum to house it. He stipulated that this was to happen 30 years after his death in order that his nephew, Matthew Baillie, and his assistant, William Cruickshank, could continue to live and work at Great Windmill Street. He appointed a number of trustees to care for and catalogue the collections and to oversee arrangements for their eventual transfer to Glasgow, “well and carefully packed up and safely conveyed”.

However, by 1799 Baillie had retired from teaching anatomy and by 1800 Cruikshank was dead. So, in the autumn of 1807, under the supervision of Mr Lockhart Muirhead, Lecturer in Natural History, the collections came, by sea, to Glasgow with the coins and medals travelling by road under the escort of “six trusty men accustomed to arms”.

However, by 1799 Baillie had retired from teaching anatomy and by 1800 Cruikshank was dead. So, in the autumn of 1807, under the supervision of Mr Lockhart Muirhead, Lecturer in Natural History, the collections came, by sea, to Glasgow with the coins and medals travelling by road under the escort of “six trusty men accustomed to arms”.

The original museum, designed by William Stark, was the first of many similar museum buildings in Britain. It was located in the original University grounds, just off Glasgow High Street.

When the University moved west to its present location in 1870, the Hunterian collections were relocated to the Gilbert Scott building, where the Museum remains today. To begin with, the whole collection was displayed together, but gradually sizeable sections were removed to other parts of the University.

The Zoological collections are now housed within the Graham Kerr Building, the art collections in the Hunterian Art Gallery, and the books and manuscripts in the University of Glasgow Library. Hunter’s anatomical collections are housed in the Thomson Building, and his pathological preparations at the Royal Infirmary, Glasgow.