From feeding nations to saving lives

Shaping vaccination strategies against rabies

Rabies is the one of the deadliest viruses on Earth. Once symptoms appear, it’s 100% fatal. Every year, the disease claims more than 60,000 lives, nearly half of them children. Yet, despite its severity, it’s entirely preventable.

Now, informed by University of Glasgow research, a global initiative targets the rollout of lifesaving human rabies vaccines to 67 countries aiming to save nearly 500,000 lives over the next ten years. We’re taking rabies on with our data. We’ve proven what works. What if we could eliminate rabies for good?

Professor Katie Hampson, infectious disease ecologist at the University has been at the forefront of rabies research for two decades, working across sub-Saharan Africa to understand how the disease spreads and how best to stop it. Her work has shaped global vaccination strategies, World Health Organization policy, and helped secure major funding from Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance.

Understanding rabies dynamics

“Rabies is horrific,” she says. “But it’s also one of the few diseases we can eliminate entirely with the tools we already have.” Leading a multidisciplinary team, Professor Hampson studies the complex barriers to rabies control, including high vaccine costs, remote communities and slow response times.

Professor Hampson’s work combines field investigations, molecular epidemiology and computational modelling to understand rabies dynamics across diverse landscapes, varying population densities and distinct cultural contexts: “We want to know how rabies persists and spreads, and how to deliver control strategies effectively in different settings.”

Cost effective approach

Globally, dogs are responsible for 99% of human rabies cases. Vaccinating dogs is 50 times cheaper than vaccinating humans, making it the most cost-effective way to stop transmission. Professor Hampson champions a One Health approach that integrates human, animal and environmental health. She is trialling community-based dog vaccine distribution. By placing vaccines directly in rural communities and training livestock field officers to administer them, her team is overcoming logistical barriers and improving access.

“We want public health and animal health sectors to work together,” she says. “If a field officer diagnoses a rabid dog, they can alert local health workers to ensure emergency human vaccines are available. That kind of coordination is vital.”

Shaping policy

Her work has already helped shape Tanzania’s national rabies control strategy, recently endorsed by the World Organisation for Animal Health. Professor Hampson says: “Together with an amazing group of collaborators, our team undertakes science that informs policy and shapes advocacy. We’re proud our work has catalysed funding and informed vaccine investment strategies worldwide.”

Human impact

Scientific data alone, however, cannot convey the traumatic personal toll of the disease. In a recent, harrowing encounter in Tanzania, Professor Hampson witnessed why research towards the ultimate goal of rabies elimination is so vital.

“A 12-year-old boy - the same age as my son at the time - had been admitted to hospital,” she recalls. “He had all the classic signs of rabies. He was salivating excessively and had a glazed look. He could stand but couldn’t walk. The really difficult thing to see was that his father and brother were in denial. They didn’t want to believe what was happening. But there was nothing that could be done. It was just horrible.

“It’s a tragic story but it shouldn’t have to happen. I’m hopeful that with the tools we have on hand, and with investment from Gavi making vaccines more accessible, other families won’t have to suffer like that. With concerted efforts globally, we can put an end to this disease for good.”

At University of Glasgow, we’ve been changing the world for 575 years and now, our life-saving research is helping the World Health Organization build a future free from rabies.

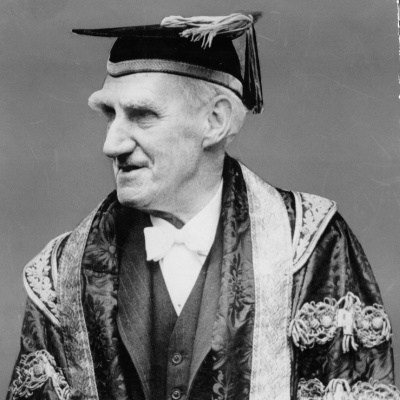

John Boyd Orr

John Boyd Orr, Baron Boyd Orr of Brechin (1880–1971) was the first scientist to show a link between poverty, poor diet and disease.

His research during the early 20th century demonstrated how malnutrition was the root cause of widespread health problems and laid the foundations for modern nutritional science. He pioneered research into animal and human nutrition, playing a leading role in shaping food policy during WW2.

Boyd Orr was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1949 for his work combatting global hunger, promoting food security and the establishment of the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organisation.

Find out more

Infectious disease ecology researches complex interactions between hosts, pathogens and the environment, particularly factors that affect patterns of pathogen occurrence and transmission.