Equality and Diversity in the Life Sciences App

In 2021, the co-chairs of the then-School of Life Sciences Athena Swan SAT - Dr Nicola Veitch, Dr Stewart White, Dr Vic Paterson - developed a teaching resource on Equality and Diversity in the Life Sciences for our level 1 and 2 students.

After securing a Wellcome Trust ISSF grant, the trio worked with six student interns to develop authentic scenarios and role model videos and deliver problem-based learning tutorials in a resource shared via an app, first launched in April of 2021.

Download version 2.0.0 of the Equality and Diversity in the Life Sciences App at the links below:

INTRODUCTORY SERIES

Introduction to E&D

E&D in Academia

Discrimination

Protected Characteristics

Introduction | Video Transcript

Introduction to Equality and Diversity

Hi everyone. Welcome to this educational resource about Equality and Diversity. This educational resource has been developed at the University of Glasgow at the School of Life Sciences. It hasbeen supported by Athena Swan and funded by the Welcome Trust. The resource has been developed by three staff members, Dr Nicola Veitch, Dr Stewart White and Dr Victoria Paterson, who are all co-chairs of Athena Swan. Furthermore, by the group of six student interns, Sonya, Declan, Lara, Jack, Holly and myself, Annamaria. In this video Sonya is going to introduce you to the basic concepts linked to Equality and Diversity.

These are the Level 1 sessions in Equality and Diversity in the School of Life Sciences. These sessions are being supported by AS and funded by the Welcome trust. They were designed by a team of 6 interns and 3 staff members from the University. I’m Sonya and will be giving this introduction along with two other interns Declan and Annamaria.

So, what is Equality and diversity? ‘Equality and Diversity’ is a term used in the UK to define and promote equality and diversity as human rights and as defining values of society. Equality is about ensuring everyone has an equal opportunity and is treated fairly. Diversity refers to being diverse, i.e. different, and that all of us our unique individuals. Promoting equality and diversity as human right and as values of society, ensures no one is discriminated against because of the characteristics that makes them different from others.

The University of Glasgow’s Equality statement reads as following:

The University of Glasgow is committed to promoting equality in all its activities and aims to provide a work, learning, research and teaching environment free from discrimination and unfair treatment.

In turn, University of Glasgow’s professional value is:

Embracing diversity and difference and treating colleagues, students, visitors and others with respect.

Part of ‘Equality and Diversity’ is captured by the Athena SWAN charter, which was established in 2005. The goal of Athena SWAN is to encourage and celebrate gender equality in higher education and research institutions, by promoting representation, progression, and success for all. Since it established, Athena SWAN has expanded its remit to all protected characteristics defined by the Equality Act 2010.

So, what is the Equality Act 2010? The Equality Act forms the basis of anti-discrimination law in the UK. It legally protects individuals from discrimination in the workplace and wider society. This means it is illegal to discriminate against someone based on characteristics that are described as ‘protected’.

These are the nine protected characteristics that fall under the Equality Act:

- age

- disability

- gender reassignment

- race

- religion or belief

- sex

- sexual orientation

- marriage and civil partnership

- pregnancy and maternity

This means it is illegal to discriminate against someone based on these nine characteristics.

E&D in Academia | Video Transcript

Equality and Diversity in Academia

Hi everyone. Welcome to this educational resource about Equality and Diversity. This educational resource has been developed at the University of Glasgow at the School of Life Sciences. It has been supported by Athena Swan and funded by the Welcome Trust. The resource has been developed by three staff members, Dr Nicola Veitch, Dr Stewart White and Dr Victoria Paterson, who are all co-chairs of Athena Swan. Furthermore, by the group of six student interns, Sonya, Declan, Lara, Jack, Holly and myself, Annamaria. In this video Jack is going to introduce you to Equality and Diversity related issues in academic environments.

This is the level two course in equality and diversity in the school of life sciences. This course has been supported by Athena SWAN and funded by the Wellcome trust and was designed by a team of six interns and three staff members at the university. I'm going to be giving this introduction along with two of the other interns Lara and Holly and I'm going to start-off by defining what we mean by diversity and equality.

First off is diversity and this is sometimes hard to define because it exists at different levels. At the individual level, everyone is diverse because of their own unique set of skills, experiences and a combination of characteristics. By characteristics I mean things like sex, age, religion, disability status and many other factors. Groups and workplaces can also be diverse but only if there's a mix of different characteristics within the people in their workplace so a mix of different people who can bring different perspectives and different ideas to a group.

Diversity also exists within characteristics, so people who are the same sex or the same religion or with the same disability status don't all think the same, act the same or believe the same things. Everyone is individual because of their combination of different experiences and skills and characteristics. Most importantly diversity is not about categorising people, it's about appreciating the individual.

Equality is different, it's about ensuring people are given opportunities based on their skills and abilities. A lot of people face challenges in reaching their career goals because of characteristics like sex, race, religion, orientation etc. and the barriers that are put in place, which prevent some people from getting to reach their career goals. This can happen because of history in the workplace - where the workplace has been designed to work for mainly one group of people but also it's because of our own biases, whether they're unconscious or conscious, which prevent promotion of certain people or prevent us from making job adverts that appeal to everyone or preventing people

from being hired.

Many sectors haven't yet achieved true equality in their staffing and the higher education sector is one of many examples. In the UK if we look at male and female staff and students, we can start to see the imbalance. At undergraduate level students are 57 per cent female and 43 per cent male. Whilst this isn't great that it's not 50/50 there's a lot of factors that go into play here and I'm using this as a baseline showing the undergraduate cohort as being mostly female.

When you look into the academic staff levels the balance swings to being mostly male - 54 per cent are male and 46 per cent are female again this is close-ish to 50/50 but we'd rather it was in fact a reasonably equal proportion.

The big problem that you see is when you reach professor level and you see that three quarters of professors are male and only 27 per cent of professors are female. This is sometimes called "the leaky pipeline of women in academia" - where from undergraduate level right up to the top level of academic careers the proportion of women drops. I appreciate that not everyone will identify as male and female but I'm just using these as they are the statistics that are available.

When we look at race in undergraduate and staff in UK universities there's also a problem. At undergraduate level it's 76 per cent white, which is actually slightly lower than the UK proportion, 12 per cent Asian, 8 per cent Black and 4 per cent mixed race in the student body proportions. This is probably influenced by the fact that this includes international students, which would naturally make for an increase in diversity in race.

However, as soon as we go into academic jobs and when we look at the proportions of black people and mixed-race people, the proportion of black people has dropped by a quarter the proportion of mixed-race people has dropped by half and Asian people have dropped by one percent. In fact, the proportion of white people is 85 % in all academic jobs which is higher than the average UK proportion of around 82 per cent to 84 per cent. At professor the change is even greater, 91 per cent of professors are white which would make it roughly 7 per cent higher than the UK proportion, less than 0.7 per cent [of professors] are black - which is 140 black professors in the entire UK.

Then finally if we look at disability at undergraduate level, 15 per cent of students would state they have a disability as defined by the equalities act (2010) - this is close to the UK-wide proportion of 18 per cent and seems to be relatively representative given that the people in UK universities are generally younger and more disabilities develop as you get older. However, when you look into staff, only 4 per cent of academic staff declare themselves as having a disability whereas 96 per cent said they don't have any disability and a professor level this is similar. What this might indicate is that disabled people are either not finishing undergraduate courses, which means perhaps they're not finding it easy to achieve enough to get through undergraduate courses or they're just not entering academic staffing or a second possibility is that people aren't comfortable with disclosing disability at staff level. Either way all three examples illustrate the fact that higher education has yet to achieve a proportional equality in a lot of these different factors (characteristics). It's hard to find statistics on other characteristics, so it's just these three examples that are being used to illustrate this.

So why is actually important to have diversity and equality in life sciences? The first reason and perhaps the most intuitive is the fact that it's just simply unfair to be denied an opportunity because of things like your gender identity or your maternity status or your age. It just doesn't seem fair that things that aren't relevant to the actual job you're doing should define whether or not you should get a job or a promotion.

Also, if you give opportunities based on skills and not characteristics it means that you've got the best chance of the best person for the job getting that job and therefore that job being done at its best.

Finally, when we think about science careers whether in academia or outside of academia, we need a lot of analytical thinking and we need new ideas. A diverse working group can improve those ideas because it brings in different perspectives and experiences.

Discrimination | Video Transcript

Discrimination

Hi Everyone. Welcome to this educational resource about Equality and Diversity. This educational resource has been developed at the University of Glasgow at the School of Life Sciences. It has been supported by Athena Swan and funded by the Welcome Trust. The resource has been developed by three staff members, Dr Nicola Veitch, Dr Stewart White and Dr Victoria Paterson, who are all co-chairs of Athena Swan. Furthermore, by the group of six student interns, Sonya, Declan, Lara, Jack, Holly and myself, Annamaria. In this video Declan is going to give you an introduction about the different types of discrimination.

So, what does it mean to discriminate against someone?

There are four main types of discrimination:

- Direct discrimination

- Indirect discrimination

- Harassment

- Victimisation

Direct discrimination

Direct discrimination occurs where someone is treated less favourably than others because of:

- a protected characteristic they possess – this is ordinary direct discrimination

- a protected characteristic of someone they are associated with, such as a friend, family member or colleague – this is direct discrimination by association

- a protected characteristic they are thought to have, regardless of whether this perception by others is actually correct or not – this is direct discrimination by perception.

Direct discrimination in all its three forms could involve a decision not to employ someone, to dismiss them, withhold promotion or training, offer poorer terms and conditions or deny contractual benefits because of a protected characteristic.

Indirect discrimination

This type of discrimination is usually less obvious than direct discrimination and is normally unintended. In law, it is where a ‘provision, criterion or practice’ involves all these four things:

- The ‘provision, criterion or practice’ is applied equally to a group of employees/job applicants, only some of whom share a certain protected characteristic

- It has (or will have) the effect of putting those who share the protected characteristic at a particular disadvantage when compared to others without the characteristic in the group

- It puts, or would put, an employee/job applicant at that disadvantage

- The employer is unable to objectively justify it - what the law calls showing it to be ‘a proportionate means of achieving a legitimate aim’.

Harassment

Harassment is defined as ‘unwanted conduct’ and must be related to a relevant protected characteristic or be ‘of a sexual nature. It must also have the purpose or effect of violating a person’s dignity or creating an intimidating, hostile, degrading, humiliating or offensive environment for them.

Generally, harassment:

- includes bullying, nicknames, threats, jokes, ‘banter’, gossip, intrusive or inappropriate questions and comments, excluding an employee (for example - ignoring them or not inviting them to meetings), insults or unwanted physical contact

- can be verbal, written or physical

- is based on the victim’s perception of the unwanted behaviour rather than that of the harasser, and whether it is reasonable for the victim to feel that way

- can also apply to an employee who is harassed because they are perceived to have a protected characteristic, regardless of whether this perception by others is actually correct or not

- can also apply to an employee who is harassed because they are associated with someone with a protected characteristic or witnessed harassment

- can also apply to an employee who witnesses harassment because of a protected characteristic and that has a negative impact on their dignity at work or working environment, irrespective of whether they share the protected characteristic of the employee who is being harassed.

Victimisation

Victimisation is when an employee suffers what the law terms a ‘detriment’ - something that causes disadvantage, damage, harm or loss because of:

- making an allegation of discrimination

- supporting a complaint of discrimination

- giving evidence relating to a complaint about discrimination

- raising a grievance concerning equality or discrimination

- doing anything else for the purposes of (or in connection with) the Equality Act 2010, such as bringing an employment tribunal claim of discrimination.

Protected Characteristics | Video Transcript

Protected Characteristics

Hi everyone. Welcome to this educational resource about Equality and Diversity. This educational resource has been developed at the University of Glasgow at the School of Life Sciences. It has been supported by Athena Swan and funded by the Welcome Trust. The resource has beendeveloped by three staff members, Dr Nicola Veitch, Dr Stewart White and Dr Victoria Paterson, who are all co-chairs of Athena Swan. Furthermore, by the group of six student interns, Sonya, Declan, Lara, Jack, Holly and myself, Annamaria. In this video Holly is going to give you an introduction about the nine protected characteristics that are embedded into the Equality Act 2010.

How does the law address equality and what are your rights and protections in the workplace from discrimination as you enter a career in life science? Employers of all sizes in all sectors have to comply with equality legislation to make the workplace a fair environment. Under the equality act (2010) everyone is protected from discrimination harassment or victimization based on any one of their protected characteristics in the workplace and beyond. There are nine protected characteristics covered under the equality act. These are age, disability, gender reassignment, civil partnership, pregnancy and maternity, race, religion or belief, sex and sexual orientation. Let's have a look first at the three main types of unlawful behaviour under the act.

Direct discrimination is when someone is treated less favourably than others because of either: a protected characteristic that they themselves possess and this is known as ordinary direct discrimination; a protected characteristic of someone that they're associated with, this is direct discrimination by association; or a protected characteristic that they are thought to have and this is direct discrimination by perception.

In all its three forms direct discrimination could involve a decision not to employ someone, to dismiss them, withhold promotion or training, offer poorer terms and conditions or deny contractual benefits because of their potential characteristic.

Indirect discrimination is usually less obvious and normally unintended. In law it is where a provision, criterion or practice involves all of the following: firstly, it applies to everyone in a group of employees or job applicants, only some of whom share a certain protected characteristic; it has or will have the effect of putting those who share the protected characteristic at a particular disadvantage when compared to others without the characteristic in the group and then puts them at that disadvantage; and lastly the employer is unable to objectively justify it and this is what the law calls showing it to be a proportionate means of achieving a legitimate aim.

The equality act doesn't actually define what a provision criterion or practice is however it's most likely to include an employer's policies procedures requirements rules and arrangements even if informal and whether written down or not. Examples might include recruitment selection criteria, contractual benefits or any other workplace practice.

Harassment is defined as unwanted conduct and must be related to a relevant protected characteristic or be of a sexual nature. Harassment has the effect of violating a person's dignity or creating an intimidating, hostile, degrading, humiliating or offensive environment - this can include bullying, nicknames, jokes, banter, gossip, insults and/or unwanted physical contact. It can be verbal, written or physical. It's important to note that harassment is based on the victim's perception of the unwanted behaviour rather than that of the harasser. This means that by saying comments were just banter is no defence.

Victimisation is when an employee suffers what the law calls a 'detriment' and this is something that causes disadvantage, damage, harm or loss because the employee has made an allegation of discrimination, they've supported a complaint of discrimination, or they've given evidence relating to a complaint about discrimination, or they've raised a grievance concerning equality or discrimination and anything else done for the purpose of or in connection with the equality act such as bringing an employment tribunal claim of discrimination. Victimisation may also occur because an employee is suspected of doing any one of these things or it's believed they're going to do so. A detriment could be the employee being lame build a trouble-maker being left out and ignored being denied training or promotion or being made redundant because they've supported a discrimination claim.

Every single one of us have what is known as protective characteristics these are aspects of our identities including our sex, age and race that the equality act makes it unlawful for others to discriminate against. There are nine protected characteristics under the equality act 2010. The definitions of each characteristic can be found in the Moodle glossary and we would recommend that you go and look at them so let's take each and turn and highlight any specific points about each of the protected characters.

First is age, and we should note that ordinary direct discrimination based on age is actually one of the rare cases where discrimination may be justified by law. The easiest example to think of with this is the national minimum wage so this is where two people may be doing the same job both on minimum wage but are paid differently because one is older and one is younger. A person has a disability if they have a physical or mental impairment which has a substantial and long-term adverse effect on that person's ability to carry out normal day-to-day activities.

This includes illnesses such as cancer and progressive conditions like multiple sclerosis. It's unlawful to treat a disabled person unfavourably because of something connected with a disability: for example, a tendency to make spelling mistakes due to dyslexia. Employers are accountable for making reasonable adjustments these are changes and adaptations to the physical or working environment, that removes or minimizes the impact of the employee's impairment in the workplace.

Gender-reassignment refers to the process of transitioning from one gender to another. Previously people reassigned in their gender had to be under medical supervision to be covered but this is no longer the case. It's discriminatory to treat transgender people less favourably than others for being absent from work because they are about to undergo are undergoing or have undergone gender reassignment than they would be treated for being absent just because they were ill or injured. Both same sex and opposite sex couples can have their relationship legally recognized by marriage or civil partnership. Civil partners must not be treated less favourably than married couples and we should note that single people and couples not in relationships legally recognised are not protected. As well as direct discrimination by perception or association, harassment because of this characteristic is not covered by the equality act.

Pregnancy is a condition of being pregnant or expecting a baby, maternity refers to a period after birth and it's linked to maternity leave in the employment context. Protection against maternity discrimination is for 26 weeks after giving birth and this includes treating a woman unfavourably because she's breastfeeding. We should note that for pregnancy and maternity the protection is against unfavourable treatment as opposed to less favourable with the other characteristics so this means that an employee or job advocate must not be disadvantaged because of her pregnancy or maternity without the need to compare to how someone else is treated.

The equality act protects employees from discrimination harassment and victimisation because of the protected characteristic of race. Race often includes different elements that often merge including colour, ethnic origin, national origin and nationality. Religion refers to any religion including a lack of religion and similarly belief refers to any religious or philosophical belief and includes a lack of belief. Generally, a belief should affect your life choices or the way you live for it to be included in the definition.

Sex is assigned to someone on the basis of their primary sex characteristics and reproductive functions sometimes we can find that the terms sex and gender are interchanged to mean male or female but we'll note that this is not the correct definitions and again have a look in the Moodle glossary if you're unsure. In UK, law sex is understood as being binary with a person's legal sex being determined by what is recorded on their birth certificate If you're treated unfairly because you're a man or a woman this is sex discrimination. It applies equally to men and women of any age, so it includes girls and boys.

Sexual orientation refers to whether a person's sexual attraction is towards their own sex the opposite sex or both sexes. The equality act protects employees from discrimination harassment and victimisation based on the fact they're bisexual, heterosexual or lesbian/gay.

It's important to remember that although the equality act breaks down individual protected characteristics as individual factors real people are multifaceted and may have different issues based on their whole selves and their intersecting identities. For example, a gay white Christian woman will have a different experience and face different barriers throughout her life than a gay black atheist man, although both of them identify as gay and may experience homophobia. This idea can be captured by the term intersectionality - the cumulative complex manner in which the

effects of different forms of discrimination combine, overlap or intersect. To break that down, it essentially means that discrimination doesn't exist in a bubble, different kinds of prejudice can be amplified in different ways when put together. This is something we should consider when we are thinking about barriers - unique people have unique experiences.

We should also use caution when we're describing barriers the quality act protects everyone based on their protected characteristics; however, we should note that the protected characteristics are not the problem the structures and systems of power against them are. For example, women still experience gender related issues such as the gender pay gap and sexual harassment - being female is not a barrier in your career, patriarchy is a barrier and similarly being black is not a barrier - white supremacy and racism that persists in our society is the barrier.

ROLE MODELS IN STEM | VIDEO SERIES

Dr Iain Stott

A computational ecologist and lecturer at Lincoln, Dr Scott discusses his experience of being a gay man working in research. Dr Stott talks about the lack of any clear limitations he has experienced in his career, choices made for personal safety when considering location of new jobs and being visible as a gay academic.

Video Transcript

Dr Iain Stott | Video Transcript

Could you tell us a bit about yourself?

My name is Iain; I am a gay man. I have recently started a job as a lecturer in Ecology at the University of Lincoln. I am 32 now and completed my PhD 8 years ago now in 2012 and that was also in the UK at the University of Exeter and since then I have moved internationally so I had my first post-doc also at Exeter but based in Cornwall, in the campus down there and then I moved to Germany for my second post-doc. I was based in a small town in the north of Germany, the north-east of Germany and then I moved to Denmark, lived there for 3 years again in quite a small town. It’s west of Copenhagen, called XXXX and following that, I had my second half of my second post-doc there, did my fellowship there as well and then moved back to the UK to start this job mainly because I wanted to be closer to family.

Have you faced any barriers in relation to your protected characteristics?

I would say I am quite fortunate, so I am gay but I am also white and I am also male. There is all sorts of privileges that come with those second two characteristics. I have lived and worked in very liberal societies- the UK is liberal, Germany is liberal, Denmark is liberal, very liberal actually, and so I can’t say that I have faced any or that I am consciously aware of any barriers that I have faced to my career. That’s not to say that things may have happened to me that I am not aware of so whether there’s any kind of systemic issues which I am not aware of that have hindered me or my progression or whether there’s any biases unconscious or otherwise that I have interacted with or not interacted with as a result of that. So, I wouldn’t say I have faced any barriers but there are also things that I may not be aware of. Although I wouldn’t say in terms of my career there are any barriers there is also certain barriers to moving and living and having a fulfilling life which may actually have had more of an impact. Because I have always lived in quite small towns, it’s been quite difficult for me to have a community of other LGBT people around me. LGBT people often end up moving to larger cities to be part of larger communities and also just because it’s inherent to the fact that the town is quite small. So I think that’s something that I have maybe missed out on. Of course I could have moved to larger cities but opportunities arise in certain places and the type of research you do, there are only going to be a handful of places in the world that do exactly what you do and have jobs available to you. Those places happen to be where I’ve ended up. SO I think my life could have been more fulfilling in that sense. I think that dating could have been easier, so people don’t think about these sort of things necessarily, maybe in the background of their mind but there are more barriers to LGBT people in that sense. It’s actually one of the reasons why I have chosen to move away from places I have been in the past that more social, personal life aspect. Denmark in the sense of how it fits with my values is a very liberal and progressive place was great but in the end, it socially just didn’t fit me. Not barriers, but my identity has impacted my life and impacted my decisions in those ways.

Do you think visibility of LGBT people in science is necessary? How do you personally go about being visibly out?

Everyone has their own personal experiences. You can’t just be expected to be open and out with your identity just because of your identity, that’s really unfair right. I live my life assuming people assume that I am gay. It’s the easiest way for me. If I met me, I think I could tell that I am gay. From a student perspective, I don’t really want students running around and wondering what my sexuality is. I would like to be open and visible for them. What I tend to do very early on in my teaching is drop in an anecdote about an ex-boyfriend or something like that so they go oh right okay, that’s fine he’s gay and maybe if there is a student, a gay student in the class and they do find it helpful to know that then great. If they feel that or they need to come and talk to me about anything then great as well. So in terms of students that’s how I tend to manage it.

What support or resources are out there for LGBT people in science? What has helped you?

Stonewall is a really good resource, get involved with societies. So I have done a great deal of work with the British Ecological Society and they have started producing things like advice booklets and advice for people going on fieldwork who identify as certain minorities particularly LGBT and also being female on fieldwork. But also getting involved with those societies apart from having the resource it helps you meet people. I have met a great deal of people through this LGBT network that we run with the BES. We run a social at every conference and it’s proved really successful actually. As an LGBT person it’s quite difficult because you’re not necessarily visible, right. You can’t walk past someone and say oh yes, they’re gay, or they’re trans or they’re bisexual so having a forum where you can bring all of these people together in a safe space where they can be open about their identity is actually a very valuable thing I think.

Do you have any advice for students?

It’s important to be open to ideas. I had never really envisaged myself living abroad. Growing up I didn’t really know anyone living abroad and certainly, no one from my family had ever moved. I think being open to these things and trying to be quite confident about it if you can is really important but at the same time you’ve got to balance that against a) your safety and also your happiness as I’ve discussed. I have definitely not applied for jobs because of where they are or what they’re doing. One example for me is the southern states of the US where there are lots of jobs available and lots of jobs actually in my area. Although small university towns can be very liberal, I actually personally never really felt that was a choice that I wanted to make for myself just in case. So you do have to be mindful of what your experiences might be like if you are going to be part of a project that does any kind of fieldwork in a country where your identity is illegal, you need to be really wary of that. That’s a big piece of advice is to bare in mind your personally identity when you’re making those choices.

Dr Clara Barker

A trans-woman and materials scientist at Oxford, Dr Barker discusses barriers she has faced, examples of discrimination and the lack of LGBTQ+ role models, how it is possible to be trans and a scientist, positive changes and the work that still needs done.

Video Transcript

Dr Clara Barker Video Transcript

Can you tell us a bit about yourself?

I’m Clara Barker, I’m a material scientist at Oxford University, I manage the Centre for applied superconductivity, and I’ve spent the last 10, 15 years working on thin film material science. I’m also the Dean of Equality and Diversity at Lineker College in Oxford. Currently I’m a member of the equality and diversity committee for the Royal Society as well so I’m just collecting titles as I go along really.

Have you faced any barriers in relation to your protected characteristics?

I’d say that my barriers, the barriers I faced were probably to a large degree, ones that I created myself because I didn’t have those role models. In 14, 15 years in science and engineering I saw two out gay people and not trans people. Now I was working at labs around the world, I was going to conferences around the world, I was a lot of places and I saw two people. And so if you’re not seeing people like you, you figure well they are obviously not allowed to be gay or bi or trans in STEM. So because I didn’t see any trans people I figured once I transitioned that was it, my career was over, my science career was over. And to be honest, I think it depends what group you’re in I think that those barriers would be faced in some places so once I came out I was very lucky that I transitioned whilst I was applying to new jobs. I did come out to people in my old job and there were definite…. there was a little bit of discrimination, but it didn’t affect me at that point because I was already leaving. There were also some amazing people. I came out and, like I say, got my new job. I had expected discrimination, but they were actually really cool, and I was quite lucky in that regard. When I was applying for jobs there were people that are like: “Oh, we’ve got a job for you whenever you want; we really want you,” and it’s like here’s my new name and it’s like: “We don’t have jobs; we’re sorry we’re just full right now!” And you know, you can’t say this is discrimination, but it pretty clearly is. But like I say, if I’d have transitioned five, 10 years earlier then. I think that the landscape has changed quite a lot, quite quickly.

What do you think has made it easier for you to be trans in science now? What is still limiting diversity in science?

There is still discrimination, we know this. We still see. So, there are, what is it people with disabilities are 60 per cent less likely to stay in STEM, the percentage of black people in STEM are ridiculously low compared to the population. And women in stem, we’re still only 23 per cent despite being 50 per cent of the population. So these barriers are there. I think we’ve improved; I think we’ve got better guidelines in place, there’s certainly more awareness. But I think that especially, especially academic institutions don’t necessarily hold anyone to account for those guidelines we’ve got in place, so you are at the mercy of happening to have a fantastic manager, supervisor, department- even within Oxford. My department is fantastic, my college is fantastic, but I talk to colleagues from other departments and the stuff that I hear coming from there it’s a very different… its an imbalance. So, it’s all about your department, your group and that’s not okay. People are making complaints about things at various universities and in various companies and no ones taking them seriously. If you’ve got those guidelines, you’ve got to stand by them, you’ve got to make them mean something.

How did you cope with or overcome the barriers you faced, or felt you faced?

I took the nuclear option I’ll be honest. My assumption was I either stayed in science or I transitioned so I made the decision at a certain point that for my mental health I had to transition, there was no two ways about it. And so, I decided that my science career was over, I’m transitioning, I need to focus on me. And so, I stopped writing papers, I didn’t necessarily finish off the experiments that I should have done. And I started basically prioritising me, I prioritised me and I made the assumption that my career was over, and I only applied to my current job out of spite to prove that everyone was going to be horrible. Wouldn’t you know it, they weren’t and that really threw me for a loop! I was literally on the train back to Manchester going “oh... what, that’s not.. no! I was supposed to be able to complain about this on Twitter, what happened?” So, that’s nice, that’s good and that’s why you shouldn’t make assumptions of people.

It’s one of those things I often say, you know, you’ve got to be lucky, you’ve got to be in the right place at the right time. Don’t get me wrong, if you don’t work hard and make the most of those opportunities then they don’t come, or you don’t get them so it’s a mixture of hard work but also luck. And I got really lucky. One thing that’s definitely helped me continue and want to stay in science and do more is having this amazing online community. Once I started talking about my experience, I found other people were in the same boat. Over the last few years there’s been a lot of groups on twitter, there’s trans in STEM there’s black in STEM, there’s LGBTI+ in STEM and having those communities, being able to talk other researchers or other scientists at different career stages, from around the country in different universities, from other countries- we are no longer having to rely on our very local networks. If I was just relying on my very local network then there’s a few people that I’d be able to talk to and no one that I could get advice on being trans, specifically whereas if you open that up all these groups have come along. So just having that global, those global supports, those global networks, those global communities- and they are communities- that is what’s helped me carry on and stay in STEM because otherwise I’d feel isolated, I think.

Do you have any advice for students?

So, most of the things that we talked about- social media and those communities, find those communities. If you don’t have the support to be yourself say with your close friends of family, find that further afield. I feel so bad for people that don’t have that local, but I also know people that have found their communities further afield. So, get that support because being able to talk about these things is such an important first step just understanding. Also, just because you’re in a bad group or there’s a bad department you’re a part of, it doesn’t mean all departments are like that in your field. There are good groups and we’ve got this global network now. So, you can find out, what are this group like, what are this group like, that information is there we’ve got the networks. Know that if you really want to do your science or engineering field, if you work hard you can do it, you might just have to find the group that works. And take your time. During my postdoc I started medically transitioning. But I wasn’t out at work. I was out to my friends, I was medically transitioning but I wasn’t out in that location because I know full well that there would have been quite severe discrimination because of that and so I did it on the time scale that worked for me. I knew that my postdoc was coming to an end and then I found a group that worked. So never feel rushed, never feel rushed and just make sure it’s right for you.

What does a role model mean to you?

Role models... so I’d say that what it means to me, because it’s a difficult term to take on for yourself. But I think that a big part of role models is visibility. So seeing someone… not just seeing someone like you, which is such an important part, but also seeing someone that has similar ideas and thoughts and feelings and stuff. I mean I saw some trans people, you know, in the past but I wouldn’t… they’re not role models to me because I have a different point of view. So its visibility off someone like you but also that has similar sort of ethics or point of view or whatever. And I didn’t have those role models when I was growing up, there just wasn’t LGBTI+ visibility when I was growing up. I grew up during the 80s and 90s, my entire school and first degree were during section 28 when it was illegal to promote homosexual relationships. So there was just no discussion of LGBTI+ people. We had 4 TV channels, no internet. It was a different time and so I just didn’t have anyone that sort of resonated with me. It was really nice when the internet started gaining traction and then about 10 years ago I started seeing more people on YouTube that did resemble me and that was when I was able to be like “aha, maybe I can transition”. I took me a long time. I’ve certainly got amazing role models now there’s some fantastic people around that I have so much time and respect for, but I didn’t have them beforehand, unfortunately.

Blair Anderson

A gay man who combines studying law at the University of Glasgow with work as a coordinator for the Environmental and Sustainability team, Blair speaks about the practical, financial, and emotional challenges caused by familial estrangement brought about after coming out aged 14.

Video Transcript

Blair Anderson | Video Transcript

Could you tell us a bit about yourself?

Hi, Blair Anderson. 21. Studying Law at Glasgow Uni. Currently at my 4th year at Uni, but only at the third year of my course, because I had to take a year out due to estrangement out of financial difficulties to do with that. What else I do? I work for the Uni as well, in the Environmental and Sustainability Team.

What is estrangement?

Estrangement is basically a significant breakdown in family relationships, which leads to loosing out on practical, emotional and financial support that most people normally get from their families. What are the main reasons behind estrangement? There are lots of reasons why people become estranged, mostly to do with clashing values and beliefs between the person and the rest of the family.

What led to the estrangement from your family?

My family are really hardline fundamentalist Christians. I came out to my mum as gay at the age of 14, did not go well. So, faced with the prospect of complete rejection, I then needed to sort of backtrack and live as closeted, from the age of 14 through 21. 14 to 18 I was still living at home and I had emotionally abusive relationship with my mother, who was bullying, gaslighting and she also controlled my communications with all people. She made sure that I did not talk to anyone else about the situation, so she was able to control me that way and that was part of the reasons that I did not get help from the age of 14, because felt unable to estrange myself completely,

because at the age of 14 you do not want to opt into the care system. You don’t know what support is available for people who are estranged and you are a child and you are also a victim of emotional abuse, so you are not going to step out on your own.

At the age of 14 to 18 I was scared of full rejection, homelessness, lack of support. So, I felt that I would be closeted and get to University, so at the age of 18 I moved to University and then from 18 to 21, right now, the family relationships were breaking down.

Did you experience any difficulties after your estrangement?

When I was applying for a student loan, there was no way for me to get independent student status. Loans are either for independent or dependent students and everyone is assumed to be dependent on a family, unless you meet some criteria. I was on the same student loan as someone, who was for example, living at home and who did not need to pay rent and who was getting allowances from their parents. All these parents were paying the rent for them. I was getting the same student loan, so I had to work over 25 hours a week a minimum wage job, during term time to afford rent and food. It got to the point at my third year at University that I was in rent reals. I did not have enough money to eat, I was stealing food from my work. I was not able to keep going to University and my grades were obviously suffering as I was working so much and then that was when I dropped out, but in the period between January 2019, when I dropped out and getting back to University in September 2019, I managed to change the SAAS application form so that basically now you can say that you are estranged, that’s like a tick-box, you know 25, married, estranged. You can opt into that, you can say I am estranged and therefore you are treated as financially independent and your parents income isn’t calculated into the student loan you get.

Were there any things that you missed after you were estranged?

The practical support, lots of very small ways that your parents normally provide for you that you don’t really think about. So, whether that’s, you know like buying your shop or giving you money if your laptop breaks to buy a new one or go like Christmas presents, big cash that’s something. The living thing is about feeling home. When you are a student moving between flats, I didn’t have a car obviously and I was very lucky that my friend does have a car, because I was estranged from my family I was already in rent arrears. I did not have any money. I was in a position where I was going to have to walk half way across Glasgow with all my possessions and move home, because I did not have you know like a family car to come and help, so there was lots of very small ways that you don’t always appreciate when you receive help from your family. The other big thing is about emotional support is about having a sort of safety net. Knowing that if things go wrong, you can move home and you would be fine.

What are your plans for the future?

So, I am repeating my third year and it is going fine and then I got another year at University doing my undergrad and then I am on course to graduate in 2021 probably after that I am going to do the diploma. It’s like a year-long course after undergrad law practice, so I am on track for that, which is good. There is funding, because obviously it is postgrad you have to pay for it but the University does offer some bursaries for people who are care experienced or estranged to help them out which is good and after that probably go into government, you know local government legal team, something like that.

Eve

A neuroscience student who lives with a disability caused by a spinal injury, Eve talks about the reality of living with a disability and how she is able to adapt to new things anyway.

Video Transcript

Eve | Video Transcript

Could you tell us a bit about yourself?

I am Eve, I am 19, I come from a tiny, little rural town in Cheshire, England and my undergraduate degree is Neuroscience. My hobbies…I read a lot, when I can, cook and I also craft.

Could you tell us a bit about your injury?

My injury is a prolapse disk in my spine, which basically means that when I was 13, I had an accident and the disk in my back popped out and pushes the nerves to my lower legs, which has like nerve damage.

Does your injury affect you daily life?

It does affect daily life. I had the surgery to remove the disk three weeks before I started first year of University, so I had last minute surgery to have the disk out and then I had to move 300 miles to Glasgow when I was still in recovery, so that was weird.

Is there anything that helps you to deal with your disability?

It is really easy to get depressed about it, because all of my family: my sister and parents are disabled. You could look at it and be really depressed, since you know we all got physical disabilities and they make life really hard. It is really stressful and all of that is true, but the approach we try to take is that if you don’t laugh you will cry, so you just want to laugh instead. We try to find humorous points, positives or silver linings or keep it light, because then I am not dwelling on how bad it is and how difficult it makes life. It is just another part of life that we get on with.

If you could give an advice to other disabled students what would it be?

A disability does not have to be disadvantage, it can feel like it at times, even if you try to have the positive outlook. It is not a disadvantage and it does not define you, but it is a part of you. I tried to ignore my disability and I tried to go: "It does not even affect me, it is not a problem, it should be out of sight, out of mind.’’ This does not work, because there is no escaping that I am disabled, there is no escaping the injury. Instead I just use it as another part of me to help me adapt to new situations, to help me focus on more positives than negatives, so just don’t think because I am disabled, I can’t do this, because it really doesn’t.

How do people react when you tell them about your disability?

When people first find out you are disabled and you have a spine injury, I think they struggle to see it, because they can't see it and it takes a while, but then they go: 'Oh, okay so she has to do things a little bit differently.’’ I had some people at uni and its by far not the majority, but some, who say it doesn’t count as a disability if you can’t see it. That’s not true.

What is the most important that your disability taught you?

Your studies are important, but your health is important too, so when your body is telling you that you are reaching your limit, you need to listen to that, because it is not a good habit to get into.

What are your plans for the future?

I am really interested in conditions like Huntington’s Disease and Duchenne’s Muscular Dystrophy. Obviously, since I am a Neuroscience student, I also really love genetics. So I would like to study the underlying genetic causes of those conditions and seeing how the mutations in those genes and the proteins produced cause the symptoms and trying to find a way to annihilate the effects of it

Dr Izzy Jayasinghe

A lesbian trans-woman of Asian ethnicity working as a research scientist, Dr Jayasinghe speaks about the challenges she has faced, mental-health problems that have developed due to these challenges and changes in career due to a lack of support as well as how she has found support in allies, mentors, supervisors, and her partner.

Video Transcript

Dr Izzy Jayasinghe | Video Transcript

Can you tell us a bit about yourself?

My name is Dr Izzy Jayasinghe. I’m 38. I am a UKRI future leader fellow. I am a group leader in the University of Sheffield. By research, I am a microscopist and a cell biologist, so I develop new types of microscopy to visualise cells at the very molecular level and understand how they work.

Have you faced any barriers in relation to your protected characteristics?

My protected characteristics are that I’m a woman. I am a trans woman of colour of Asian ethnicity and I am a lesbian. So in terms of issues that I have faced, they range from casual types of bigotry to more systematic biases ingrained into the systems. So more causal forms, more understated forms include being undervalued, being overworked and being questioned or undermined for my skills and expertise. And structural forms of bigotry include being denied access or being limited in terms of access to peer groups, safe spaces, being overlooked for promotions, collaborations, being overlooked or denied funding, especially repeatedly, and also being overlooked for jobs. And also, I have experienced types of racism in a range from casual racist comments, for example when someone asks me where I’m from and I say I’m from New Zealand then the follow up question tends to be: “No, where are you actually from?” So that type of casual belittling, I suppose. Ranging from that to transphobia - things like misgendering, that is using incorrect pronouns to address me, deadnaming and gatekeeping. Particularly, gatekeeping in terms of being excluded from networks and being stifled in terms of career progression.

How did this impact you?

These types of negative experiences impacted me in a number of was: mentally, it was damaging so I experienced things like loneliness, anxiety and depression throughout my post-doctoral career stages. There were times where I was diagnosed with depression and treated for it. It slowed my career progression, clearly at times and it led to unnecessary exhaustion and loss of productivity. It seeded self-doubt and eroded my self confidence at times and ultimately also led me to changing my career disciplines. So I have gone from being a cardiovascular researcher to more of a cell biologist and biophysicist because I found that initial discipline that I trained in was not particularly supportive to me. And generally, more socially, things like being excluded from social groups, difficulty in forming friendships or collaborations and those are all forms bigotry or issues I that have faced because of who I am.

How do you cope with or overcome these barriers?

For dealing with issues like that I first of all made sure that I look after my mental health and I develop mindfulness about what is going on at a given time and in relation to how I feel. Exercise is definitely a big part of that mental health strategy. Keeping my boundaries clear, not just physical boundaries but emotional and mental boundaries. I am also outspoken so if someone crosses a boundary, I tend to call them out. I also have at times reminded people of what the law says in terms of my rights and my protections. I have also got a lot of allies and mentors who have supported me and without them that would have been really difficult to progress into an independent career in research and life sciences. I have made sure that I have invested in my skills so I am always looking to grow my skills and better myself so I keep up to date and my work stays current and I stay competitive as much as possible. I have also constantly made plans about to stay ahead and stay competitive. And when I make a plan, I trust the plan and I back myself to achieve it so once I’ve made the plan, I tend not to change it too much.

Do you have any specific sources of support?

My main mechanism of support is my partner who is a really constant source of comfort and a good sounding board for me and she’s always been there. Some of my supervisors and mentors have been instrumental for me getting there, getting here. They have helped me in terms of references and encouraging me to do better and go for opportunities. Colleagues in equality and diversity and inclusion groups have been a real network of support and that’s because those spaces tend to be places where you can speak more frankly and share your lived experiences and be made sure that you are heard. And finally, students and junior colleagues definitely give me a lot of inspiration and hope especially going forward. Particularly the students, the undergraduate students, and their generation tend to be more progressive, inclusive and kind compared to the generation that I grew up in and the generations before me. And I think that progressive nature of the younger generations have really helped me.

Dr Elliott Spaeth

A disabled, neurodivergent lecturer and trans man at the University of Glasgow, who supports inclusive learning and teaching, Dr Elliott Spaeth discusses the barriers he faced, especially in relation to his neurodivergence, how he learned to cope with them, and what more can be done to empower students to embrace their neurodivergent identities.

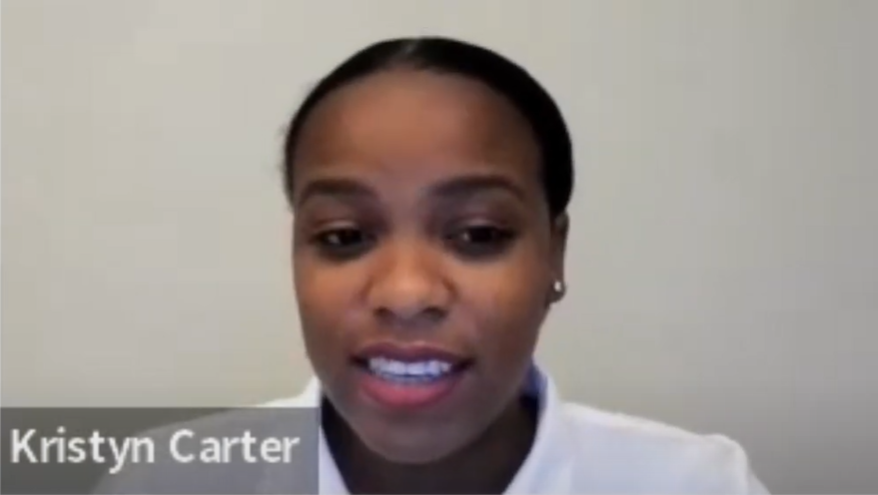

Dr Kristyn Carter

Currently working as a postdoc at Yale University, Dr Kristyn Carter was the first African American to graduate from the University of Glasgow Immunology degree programme. Here, Dr Carter shares her experiences and discusses ideas on breaking down barriers.

Role Models in STEM | Written interviews

Anonymous Lecturer

|

|

Anonymous (early 30s)Lecturer |

|

|

Introduction: I am an early-thirty-something lecturer based in the UK. I’m opting to remain anonymous: given this is a role model interview, I appreciate the irony! I’ll be writing about my mental health, which I consider to be a distinctly personal issue; one which I disclose only to my closest friends, family and colleagues. I hope you can understand this once you know more of my experiences. I first hope that I can bring attention to issues maintaining a scientific career alongside clinical, long-term psychiatric illnesses, which in my opinion have disproportionately little visibility, awareness or support. Second, I hope that my story is useful to any student who can relate to what I write and who is considering a career in research or academia. Third, I want to show it is possible to make it at least as far in one’s career as I have, alongside complex mental health issues. What barrier(s)/issue(s) do/did you face in relation to one or all of the characteristics? I am diagnosed with Bipolar Disorder type I (BD) and Generalised Anxiety Disorder (GAD), with an associated Delayed Sleep Phase Disorder (DSPD), although I’ll focus mostly on BD. It’s a potent cocktail of clinical psychiatric conditions when it comes to managing a career, and particularly in academia with its heavy pressures and high workloads. It took 10 years from my first symptoms for doctors to arrive upon the correct diagnoses. How do/did this/these impact you? Since the age of 18, every two years or so, I’ve experienced a depressive episode lasting several months. Depression for me is at best a severe lack of energy, loss of appetite, increased sleep and sluggish thoughts; and at worst means complete absence of emotion, depersonalisation, derealisation and suicidal ideation. I’ve become good at managing and hiding depression: I can attend meetings, I can teach, but it takes a lot out of me. Interacting with people is exhausting. High workloads are difficult to manage, I often miss deadlines or let people down, and I’m slow to respond to communications. I can’t physically work all the hours I usually do. My research suffers most, as it’s usually less pressing to get done. My depressive episodes always give way to manic periods, each lasting a further several months. For me, at best, low-level 'hypo'-mania means heightened energy, high mood, decreased need for sleep, and quick, joined-up thinking; at worst, full mania sees these symptoms in overdrive: relentless energy, prolonged sleep deprivation, an overwhelmingly overactive mind, vanishingly small attention span, irritability, risk-taking and paranoid delusions. Neurodiversity can be positive: with low-grade hypomania, I’m highly productive, happy, sociable, creative, and have accomplished some of my best work and achievements. Mania is far less useful. At its most extreme, when I was diagnosed with BD during my second postdoc, mania landed me in the hospital’s psychiatric ward. Not being allowed your laptop clearly negatively impacts productivity! As well as BD, my GAD exacerbates challenges of academia such as imposter syndrome, time and project management, perfectionism, job insecurity, competition, and systemic discrimination. At any one time I have constant irrational worries about something or other from that list, and more acutely, stressful deadlines or situations can induce panic. Where I to spend half as much time overthinking, checking, re-rechecking and re-visiting emails, social interactions, teaching and research, I’m sure I could get twice the amount done! Despite this, I think my anxiety drives the quality of my work and provides energy approaching deadlines, even on occasion when depressed.

How do/did you cope with and/or overcome the barrier(s)/issue(s)? Whilst once beating myself up about what I hadn’t yet achieved in my fellowship, I realised I’d spent seven-and-a-half months out of 18 either depressed or manic. Suddenly it didn’t seem so bad. My best advice is to try and keep that grounding and be understanding with yourself. I wish I could give good advice on how to let go of guilt, but honestly, it’s the number one thing I’m worst at. The flexibility of most academic working environments has been a lifeline to me. I swap weekdays for weekends if I need time off. I often work from home during depression, and to a lesser extent when manic. My DSPD means I have erratic, extreme-night-owl sleep patterns (occasionally not able to sleep until 5-6am for weeks at a time!) and I fully utilise the ability to work manageable hours. Medication is my friend. It’s not for everyone, although personally I’m happy to take it given it helps, and I generally experience few side effects. Still, it’s taken a dozen medications over many years to find a regimen that works, and even now my symptoms are curtailed rather than eliminated. Technology is also my friend. I track practically everything using apps (meds, moods, symptoms, sleep, food, exercise), which is useful in identifying patterns and early warning signals of oncoming episodes. As a scientist, I’m also just inherently interested in the data! Health, wellness and self-care, though somewhat of a trope, do help. They are not a magical cure-all for serious conditions, however. Sleep is vital! Exercise, including gym, running and yoga help me to manage all sorts of symptoms, whether distracting from unwelcome thoughts, expending excess energy or re-centring myself. Meditation and mindfulness have been invaluable to me at times also.

Do/did you have any specific support (e.g. services, people)? Specialists have been invaluable to me. I need access to and a good working relationship with a psychiatrist, and I see psychologists on an ad-hoc basis. As an academic moving nationally and internationally, identifying and building relationships with such people has presented challenges. Be diligent if it comes to moving internationally and find out in advance what care is available, what medical insurance you need, and if possible, try to identify specialists speaking your native language. Calling upon family and friends is far more difficult when living far away from home. Again, the flexibility of academia has been useful, and I’ve travelled back to stay with family and work remotely during more difficult times. I personally also like to have people nearby who are aware of my condition, if only to sometimes be able to talk openly without filtering need-to-know information. I chose to disclose my condition to my current employer, both to ensure I have full legal protection from discrimination, and to have an open dialogue and plan for managing my health. This won’t be right for all people, in all situations, in all places, with all people, but it was the right decision for me. I have a mentor and a line manager who I know I can talk to, and who have been very supportive. It’s also in their best interests that I’m a functioning and productive member of staff! Mental health awareness is gaining traction in academia, but I think long-term psychiatric disorders don’t often enjoy the visibility and sympathy of more acute or short-term, especially work-related mental health issues. I can testify from experience that managing an academic career alongside such problems is difficult to say the least, but I am also testament to the fact that it is not impossible. |

||

Dr Zoë Ayres

|

|

Dr Zoë Ayres (29)Research ScientistPhD in Chemistry

|

|

Questions asked:

|

||

|

During my PhD I struggled with my mental health. I found that there was little support for the difficulties postgraduates face during research, such as impostor syndrome, competition for academic positions and pressure to publish. There was little, if any, discussion of these common themes that PhD students face within my university, which would have made me feel less alone. There was, and still is, a stigma around mental health that needs to change. Although mental health concerns vary person to person, there are clear thematic issues that could be discussed in a wider context with postgraduate students to both raise awareness and encourage intervention when necessary. The lack of support around mental health as a postgraduate made me feel incredibly isolated, and during parts of my PhD I experienced suicidal ideation for the first time, having never had mental health issues up to that point (or after for that matter). I tried several different ways of trying to cope with my own mental health concerns. I went to university counselling sessions. I found the support to be very generic, with the psychologist unable to truly understand the issues I was facing. Further, I looked at the university wellbeing services and found them to be orientated around undergraduates, with the support such as 'how to deal with exam stress' that was not applicable to me. In the end I reached out to my doctor and was prescribed anti-depressants for the remainder of my PhD. This helped considerably. Peer support was the real place I found the strength to continue with my research. On eventually opening up about how I was feeling I found that a large number of my peers were also struggling. My peers and I started to support one another, celebrating small achievements and acting to check-in with one another and how we were feeling on a regular basis. It really helped acknowledging that the highly pressurised working environment we were working in was toxic. In order to raise awareness around mental health issues that postgraduates face, I now am an active mental health advocate, primarily on Twitter. There I make infographics to disseminate information to the PhD community to help students make sense of how they are feeling, so that they never have to be in the lonely, isolated situation I was in. |

||