Urban great tits have paler plumage than their forest-living relatives

Published: 24 August 2023

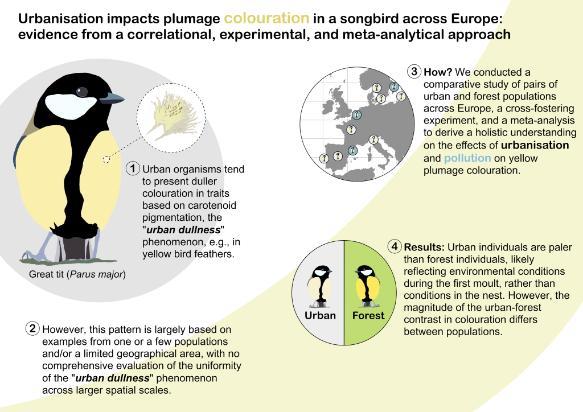

New research has revealed that some great tits may be more brightly coloured than others, with urban birds found to have paler plumage than their countryside counterparts.

Known for their striking yellow breast feathers and distinctive song, great tits are a common sight in gardens and countryside alike. Now, new research has revealed that some great tits may be more brightly coloured that others, with urban birds found to have paler plumage than their countryside counterparts.

The latest study, led by researchers at Lund University, Sweden, and the University of Glasgow, analysed feather samples from great tits in cities and forests around Europe. The researchers found that urban great tits are often noticeably paler than their countryside relatives, with dietary differences thought to be the main cause. Feather colour plays a number of significant roles in bird health. Colouring can influence mating selection, deterring predators and camouflage, and can therefore strongly impact a bird’s survival chances and likelihood of reproductive success.

The distinctive yellow colour in the great tit’s feathers comes from pigments called carotenoids which are found in food sources. The great tits get these nutrients from the insects they eat, who, in turn get carotenoids from the plants they feed on. This new research suggests that urban great tits are not able to consume as many carotenoids from their food as their countryside counterparts, and possibly fewer than they might need to stay as healthy.

As well as impacting the colour of the great tits’ feathers, carotenoids are also important antioxidants that help the body combat the toxic effects of pollution. The paler plumage of urban great tits could also suggest that these birds have weaker defences against pollution’s adverse health impacts.

Dr Pablo Salmón, who carried out the work at the School of Biodiversity, One Health & Veterinary Medicine but who is now based at the Institute of Avian Research in Germany, said: “The paler yellow plumage of urban great tits indicates that the urban environment affects the food chain, although we find that the magnitude of the effect is not the same across cities in Europe.”

As urban areas expand, animals increasingly find themselves living in towns and cities. While some animals may benefit from milder temperatures and fewer natural predators in urban settings, they also have to cope with pollutants and changes in their diet. Previous research has shown that animals in cities are “duller” in terms of yellow-orange-red colour tones compared to their non-urban counterparts. However, these studies have only focused on single geographic locations.

Hannah Watson, biology researcher at Lund University, and one of the authors of the study, said: “We used feather samples collected from great tits in cities and forests across Europe. Different methods all confirmed that urban great tits are paler.

“Our findings suggest that birds in the city are not getting the right diet. This can help us understand how to create urban environments that are more beneficial for biodiversity. By planting more native trees and plants in our gardens and parks we can help small birds, such as great tits, by providing them with a healthy diet of insects and spiders for themselves and their chicks.”

Surprisingly, the researchers found that the effects of cities on birds vary across Europe. For example, in Lisbon, forest great tits displayed much brighter feathers than city great tits. In Malmö, on the other hand, the difference in plumage between city and forest great tits was considerably less noticeable.

Pablo Salmón said: “We need further studies to understand the ultimate consequences of colour differences for urban birds and why some cities appear more favourable environments than others. This will aid the development of biodiversity-friendly policies in urban design and help to improve the quality of life of both people and wildlife”.

The study is published in the Journal of Animal Ecology and funded by the Swedish Research Council and Marie Curie Career.

First published: 24 August 2023

<< News