Do people actually use the facilities in their home neighbourhood?

Published: 15 October 2018

This blog explores a key question in neighbourhood and health research: if there is a facility or amenity close to someone’s home, is it OK to assume they use it? Surprisingly, this assumption is at the heart of a lot of health and environment research.

Published on: 15th October 2018 Author: Jon Olsen

By Dr Jon Olsen, Research Associate with the , MRC/CSO Social and Public Health Sciences Unit, University of Glasgow

This blog explores a key question in neighbourhood and health research: if there is a facility or amenity close to someone’s home, is it OK to assume they use it? Surprisingly, this assumption is at the heart of a lot of health and environment research.

We often have data which tells us where facilities and amenities are, and we tend to make the assumption that proximity means use. So, for example, if we see that some neighbourhoods have more parks or more leisure facilities, we expect the people who live in that neighbourhood use them more. Understanding local amenity and facility use is important because we want to know whether / how these things affect health.

With technological advances in recent years, studies have started to collect precise data which tell us exactly where people go using global position system (GPS) devices. We no longer have to assume, for example, that if there’s a park close to a child’s home, they will visit it. The GPS tracks we collect will tell us if they did or not. That presents an opportunity to test our assumptions.

Do children use facilities they have access to in their home neighbourhood?

is interested in children’s use of facilities in and around their homes and to test whether we need GPS to research this we conducted an analysis of facility availability and facility use for 30 10-year-old children living in Glasgow. We used data from GPS devices worn by the children for eight days. These children were part of our ‘Studying Physical Activity in Children’s Environments across Scotland’ Study (SPACES).

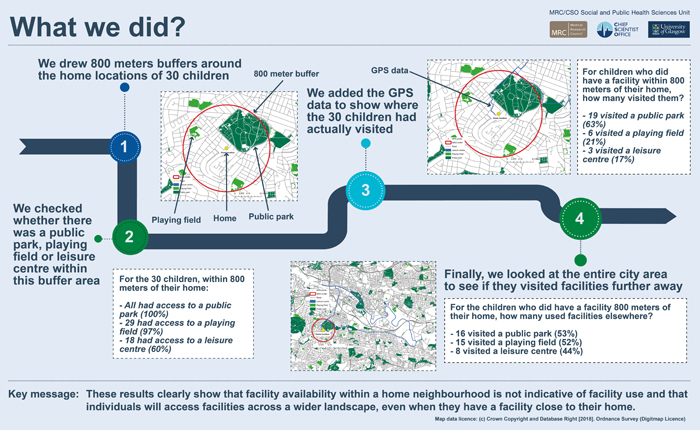

The diagram below shows what we did. Our key finding was that facility availability in the home neighbourhood is not a good indicator of facility use; the children used facilities from across a much wider area in the city, even if they had a facility close to their home. For example, 18 of the 30 children (60%) had a leisure centre within their ‘neighbourhood’ (which we defined as 800m around their home). Only 3 of the 18 actually visited that facility (as identified by their GPS tracks). Of those 18 children, 8 actually visited a leisure centre outside of their ‘neighbourhood’. We saw the same kind of pattern when exploring availability and visits to playing fields, public parks and libraries

Infographic: Measuring local facility access and use [PDF]

Are our results similar to other research?

Yes, other studies that used GPS devices have found that children do spend time outside of their immediate home area for specific purposes. For example, a 2017 study by Chambers and colleagues in Wellington, New Zealand analysed leisure time GPS data (before and after school) in 114 children aged 11 to 13 years from 16 schools, and found that 38% of their leisure time was spent outside of the home neighbourhood (using a 750m buffer around the home). Time outside of the home neighbourhood was mostly spent visiting their school, other residential locations, and fast food outlets.

These results, and those from similar studies, show that it is important not to treat what’s in someone’s immediate home neighbourhood as a good measure of what they do, or in epidemiological language ‘what they are exposed to’. We must challenge the idea that residential neighbourhood is an adequate way to capture the socio-environmental factors which contribute to health. Many people, including children, can and do access environments well beyond their immediate home neighbourhood. We think that a much wider geographic area should be considered when we’re asking questions about how environment affects health and we call this the city-wide landscape.

What does this mean for future research?

It’s clear that the ‘traditional’ approach which uses someone’s neighbourhood (often defined by a distance around their home, or an administrative area in which their home sits) to assess their access to facilities or exposure to environments is seriously flawed.

- Other methodological approaches are required to measure ‘exposure’ to environment;

- We must move beyond traditional fixed neighbourhood-health relationships (although we can’t ignore them);

- We should embrace and integrate innovative technology to explore mobility (e.g. GPS and accelerometer).

Of course, even when we’re able to see exactly where people go and what they do, we still need to understand the decisions people make about whether or not to visit or spend time at different places.

First published: 15 October 2018