Boundaries? What Boundaries?

Colin Vernall (History of Art: University of Glasgow)

| 1 | The idea of boundaries to be approached and overcome was a driving force in Modernist mythology. Whether institutional, societal or formal, artists approached boundaries and their limitations, dispensing with them and finding new spaces, values and styles. This heroic myth of the adventurer persists and its vocabulary is still used by many in the Art World. In reality this involved a certain amount of shifting the goalposts so that in the case of institutions, whilst modern art may have fought its way through the salons it re-established other boundaries in institutions such as New York's Museum of Modern Art. These limits have long been illusory and comfortingly self-imposed by a form that finds it increasingly difficult to justify its own existence. Supposedly awesome boundaries appear more like the confines of a playpen with the same nostalgic aura of something that used to present a genuine border to be crossed, an obstacle to be overcome. They used to frustrate all ambition but now think of them without letting out an involuntary aawhhh. In the case of the UK for Brit' Art read British Kite mark. |

| 2 | The art encompassed in the term Brit' Art and the period of Thatcherism (continuing under new management) that made it all possible is an example of a boundary long since rounded, surmounted and left as a glimpse of the past, its aura enhanced by lack of utility. With all the trappings of the critical art of the sixties it can still be passed off as a bit of a risk. Meredith Etherington-Smith recently wrote of the Royal Academy's 1997 Brit' Art exhibition "Sensation" that it 'has become as defining a moment in art history as the first salon des Refusés' and that it contained 'truly astonishing and often shocking works'. [1] |

| 3 | "Sensation" was partly organised by art collector and advertising executive Charles Saatchi who has been the most consistent and avid buyer of work by young British artists. His own best known work was the advertising designed along with older brother Maurice that helped ensure victory at the 1979 election for the Conservative party. For an establishment figure like Saatchi to collect this art must represent some kind of change; a boundary overcome, a border crossed: progress even? In fact this actually signifies just the opposite indicating that in this context at least no such barriers have been overcome. The forms, the alternative media of critical art have been appropriated by collectors like Saatchi, interiorising the trappings of dissent and ensuring high profile art production is incorporated in sound business rather than providing a critique of it. Homogenisation is a global reality as Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri write in Empire: 'Social subjects are at the same time producers and products of this unitary machine. In this new historical formation it is thus no longer possible to identify a sign, a subject, a value or a practice that is "outside".' [2] While art as outsider bohemianism, a privileged practice away from economic realities belongs to the past, its current role as corporate novelty is no less an impasse. |

| 4 | Early coverage of Brit' Art's ascent measured its success in increased visitor numbers to galleries, with more people attending art galleries than football matches in the UK. A more telling comparison between these two pastimes would be that they have both been subject to the absorption of their most communal and potentially liberating characteristics. They have both seen the encroachment of privatisation of public space. In the case of football open terraces with cheap access having been replaced by covered seated consumer friendly stands with corporate hospitality. The visual arts have seen the erosion of artists' run spaces which have either been incorporated into more established venues and institutions or come more and more to mimic their look and practices. |

| 5 | Conceptual Art often attempted to dematerialise the art object, reducing the importance of its value as commodity while emphasising the importance of the idea over the object. A recent unintended revival of the tendency to dematerialize saw the Momart warehouse, full of Saatchi's accumulated Brit' Art go up in smoke. Of course the idea is still paramount here, even if used by those it was initially designed to dis-empower; The work that dematerialised in the fire has been elevated to a higher status of myth, one that it's material form had no chance of emulating. |

| 6 |

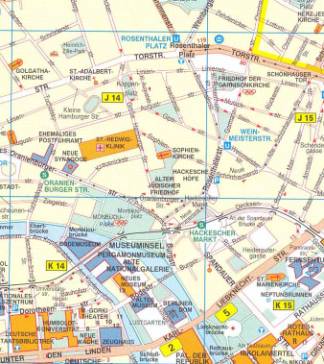

As a place whose past presents a very tangible boundary Berlin illustrates just how redundant this kind of challenge is now. A few streets West of Warschauer Strasse station, Muhlen Strasse is one of the few districts retaining a stretch of The Wall. It was bought by a Middle Eastern developer and turned into an attraction with a gallery/museum. This stretch of the wall runs along the bank of the River Spree and it's now this 30 or so metre wide area between wall and river- an area formerly inaccessible by anyone other than East German guards that is now occupied by the museum and a beer garden.

|

| 7 | The process of re-unification (economically and socially difficult for East Germans) left many Eastern districts of Berlin impoverished and dilapidated and helped reinforce the so called Wall of the Mind, a continuing sense of separation between East and West Berlinerspersisting long after visible evidence of the concrete wall is all but gone. Swathes of the former East have been renovated and a coat of bright paint applied to most of its old apartment blocks. In the space of just 5 or 6 years the district to the North of Hackescher Markt Station has gone from being a run down but affordable area of flats, squats and other occupied buildings sometimes hosting make-shift art events, to a fully fledged gallery district and expensive middle class residential district. In some streets it seems as though every second or third address is that of a small private gallery displaying contemporary work of the kind which might be seen in a similar context almost anywhere else in Europe or cities around the world. Also running through the district is Freidrich Strasse, one of the longest streets in Berlin and one which once saw large scale protests during the 1953 insurgency. These protests took place against the imposition of increased work norms by the GDR (German Democratic Republic-East Germany) government of Grotewonl and Ulbricht, basically an attempt to force more work for poorer pay and conditions from the East German working class. Among the governments most militant opponents were the largely communist workers of Berlin's construction industry, many of whom were engaged at the time in the building of Stalin Allee. Although these events are usually depicted as the first mass protests against Eastern Block governments and by implication communism, for the leftist workers of East Berlin this was their own genuinely populist uprising. |

| 8 | West Berlin has also changed. There are few of the occupied buildings and squats formerly tolerated by the old FDR (Federal German Republic-West Germany). In the pre-unification era a large section of its youth had left other parts of West Germany to avoid the military service which they didn't have to do in Berlin. The West has also fallen foul of economic recession and high unemployment yet property developers have transformed this part of Berlin no less than the East. Potsdammer Platz, which was divided in two by the wall, is almost unrecognisable from the mid 90's. Corporate architecture with an emphasis on shopping spaces seems to be the major defining characteristic of this new cityscape. The Daimler-Chrysler Building towers above a comparatively tiny public space, made to seem all the more claustrophobic by the almost equally large presence of the nearby Sony Centre. Among its restaurants, shops and cinemas the centre also contains the Berlin Film Museum, which looks a bit overshadowed here and is often closed just when its neighbours are at their busiest.

|

| 9 | The predominantly Turkish district of Kreuzberg still contrasts with more central districts but is now subject to increasing gentrification. There aren't too many impromptu exhibitions here any more although some groups of young squatters do still live alongside the local Turkish population. Berlin has the largest Turkish population of any city in the world apart from Istanbul. Though these communities are well established the fact that they remain among the cheaper districts in the city attracts increasing numbers of people looking for lower rents. Among those following this pattern are many of Berlin's artists. |

| 10 | Heike Walter exhibits widely in Berlin and around Germany. In common with most other German artists she now finds funding is far more scarce. She talks of the Berlin of the nineties and West Berlin of previous decades with a mixture of regret that things have become economically more difficult now but also disillusionment that artists along with the bulk of the population did not see the looming changes. She has seen the new gallery district near Hackescher Markt change since her first contact with the area in 1995.

|

| 11 |

The Delphina Projekt is Heike's ongoing work which has reached various stages of completion in different media over the last few years.[7] It is a collaborative work involving the participation of groups of 30 women monitoring their daily levels of happiness, anxiety and other responses. She makes work which while superficially corresponding to the kind of international style seen in these venues as elsewhere, is inclusive and non-prescriptive. It's presentation is impressive but still forms a part of her approach because it doesn't arrive on the floor of the gallery entirely predetermined as a pure statement precluding our involvement like the big works of Modernist masters and so much neo-conceptualism. However, Walter is currently in a situation where her work is accomplished and in the recent past she has gained support and opportunities but now in the newly renovated Berlin and reunified Germany those opportunities and that support are concentrated on the more established, who need it less. |

| 12 | Henrik Jacob is also producing work in Berlin and recently took part in a group exhibition with Heike Walter and around 20 other artists. He is involved with a gallery Murata and Friends which constitutes a kind of co-operative. Henrik tries to support similar approaches in other areas. "I like to go to places that have an attitude or stance I agree with whether it's a bar or a studio I try to support this kind of idea".[8] |

| 13 | He grew up in Dresden and his family only moved from the German Democratic Republic when he was 17. By leaving then he managed to narrowly avoid doing military service which was notoriously difficult in the former East Germany. After an initial period of just being glad to be in the West and not in the East German army he began to have a more critical attitude to his circumstances. His work reflects history as relayed through the media along with a glut of ephemera and mingled with a personal history which is his case is to some extent bound up with the old GDR and subsequent German re-unification. While some of his plastecine models are of prominent figures from German history such as Erich Hoeniker, Baader and Enslin they also include his mother. Another is a model of the East Berlin home of an American cowboy singer and actor Dean Read who was bizarrely taken up by the GDR establishment to become East Germany's answer to various Western counterparts.[9] In a piece called Shooting Gallery Jacob invited participants to destroy objects with similar resonances. |

| 14 | In contrast to all this, the big exhibition in Berlin this summer is at the Neue Nationale Galerie and features a large number of works on loan from New York's Museum of Modern Art. The role of this institution in the creation of Modern Art History is well established.[10] The exhibition's timing is apposite in a period of damage limitation diplomacy between the US and UK on one side and France and Germany on the other regarding their disagreement over the Iraq War. MOMA in Berlin reads like staged reconciliation featuring as it does so many old Modern European works loaned back to Old Europe reaffirming its place in civilisation along side American Abstract Expressionist cold war Modernism. |

| 15 | A combination of value judgments based in part on a cosmetic notion of what constitutes good art largely driven by corporate tastes and the concentration of enormous amounts of capital at the booming end of corporate culture as epitomised by new Berlin landmarks like the Sony centre, have ensured that in a Berlin without the Wall there are still boundaries and borders. They're just not the boundaries and borders that the romantic language of some art history and criticism like to invoke and which can always prove to have been challenged and overcome thus providing the happy ending constantly played out in scenarios such as Brit' Art.

The term Brit' Art, masks a London bias whereby the bulk of the artists, key institutions and certainly its connections to money and establishment figures like Saatchi root it firmly in the traditional metropolitan centre of power, ignoring economic disparity between the South East and the rest of the UK, as well as constitutional change that has only been achievable in a context where its effects have been minimised in advance. As in Berlin where art increasingly equates with property and exclusivity Brit' Art was instrumental in the gentrification of some parts of London. In the mid 1990's artists including Damien Hirst moved into what was then the cheap district of Hoxton. The area was soon priced out of the reach of most of its former inhabitants.[11] When increasing disparity in wealth and access aren't acknowledged the apparent irony of Brit' Art is cancelled out. The apparently self deprecating tone of the term applied as it is to art and artists, collectors and institutions who we shouldn't believe capable of any kind of patriotic nonsense or the kind of associations cloaked by it, just doesn't apply. The supposedly benign abbreviation Brit' has less populist associations in other parts of the islands. Brit' Art has consistently been the art for a prevailing neo-conservativism in the UK with its institutional support as part of Cool Britannia clichés and involvement with wealthy right-wing collectors like Charles Saatchi. |

| 16 | Fifteen years ago people still had to make sacrifices to get over and get rid of the Berlin Wall. Given the relatively intangible nature of contemporary boundaries that scale of commitment is really not necessary. Art needs to engage with what's actually happening in society but this can still be done astutely and critically rather than passively. Marcus Verhagen wrote on the subject of artists dealing with Utopianism that:

|

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

[1] Meredith Etherington Smith, 'In the Palm of His Hand', Art Review, 54 (2003), 42-47 (P.45).

[2] Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri, Empire, 2nd edn (Cambridge Massachusettes and London: Yale, 2001) p.385.

[3] See James Putnam, Art and Artifacts-Museum as Medium, Thames and Hudson, 2001 and Art Crazy Nation, Matthew Collinge, (London: 21 Publishers Ltd, 2001).

[4] BRITART, Series on BBC4 broadcast June '03.

[5] All maps taken from Berlin Atlas, Reise-Verlag, 2002

[6] Interview, Berlin, 14/06/04.

[7] See www.thealit.de.lab.searlit/teil/walter.

[8] Interview, Berlin, 15/06/04.

[9] See www.muraandfriends.

[10] See Francis Frascina and others, Modernism in Dispute (London: Open University Press, 1994) & Griselda Pollock and Fred Orton, Modern Art and Modernism, Open University BBC 2, 1982.

[11] Jess Cartner-Morely, 'Where Have All the Cool People Gone?' in The Guardian, 21/11/03.

[12] Marcus Verhagen, 'Micro-Utopianism' in Art Monthly, 272 (Dec-Jan 03-04), pp.1-4 (PP. 2-3).

eSharp issue: autumn 2004. © Colin Vernall 2004. All rights reserved. ISSN 1742-4542.