Case studies

The Standards in Scotland’s Schools etc (2000) Act confirmed Scotland’s commitment to an inclusive education system by asserting the right of every child to an education. The 2000 Act enshrined the rights of highly able learners in law by stating that education should be directed to the development of the personality, talents and mental and physical abilities of the child to their fullest potential (Section 2).

The Education (Additional Support for Learning) (Scotland) Act 2004 updated 2009 explicitly ties the education of highly able pupils into the “special education” arena. However, more importantly, the Act reconceptualised the term Special Educational Needs (SEN) and instead talked about children who might require Additional Support for Learning (ASL). SEN had become too firmly associated with pupils with disabilities and difficulties and so this new term was accompanied by a redefinition of what it means to have educational ‘needs’. The Additional Support for Learning Statutory Guidance 2017 states

The definition of additional support provided in the Act is a wide, inclusive one

and it is not possible to provide an exhaustive list of all possible forms of

additional support. Additional support falls into three overlapping, broad

headings: approaches to learning and teaching, support from personnel, and

provision of resources.

It goes on to state that “These barriers may be created as the result of factors such as the ethos and relationships in the school, inflexible curricular arrangements and approaches to learning and teaching which are inappropriate because they fail to take account of additional support needs”. Within the guidance there are examples that include highly able learners – “For example, highly able pupils may not be challenged sufficiently or those with specific reading or writing problems may not be receiving the appropriate support to help them make progress overcoming their difficulties”.

'Building the Curriculum 3' provides the framework for planning a curriculum which meets the needs of all children and young people from 3 to 18, and offers amongst other things personalisation, enjoyment and depth. Many learners require additional support in order to fully access their entitlements under Curriculum for Excellence. This includes learners who demonstrate particularly high abilities in one or more areas. Discussing how to best support these children and young people helps us to ensure appropriate learning experiences are in place.

Scotland’s approach to placing the rights of this group of learners within an inclusive framework is in many ways ground-breaking as many countries have separate legislation for SEN and high ability with others having no legislation covering those of high ability. However, a strong legislative and policy context are only part of the story as it is how these policies are enacted in schools and classrooms that will result in whether highly able learners feel supported, included and challenged or adrift, excluded and under-challenged.

The Scottish Network for Able Pupils has worked with a number of teachers across Scotland. In particular four members of staff were involved in a European Project and attended summer schools in Dublin, Ireland; Ljubljana, Slovenia and Munster, Germany to share and discuss ideas related to classroom practice. The following ideas and comments come from the work these teachers have implemented in their schools. They are designed to demonstrate how you might start to systematically plan for provision and identification of highly able learners in your school. Remember, high attainment and high achievement are not necessarily indicative of high ability.

Model for Reflection

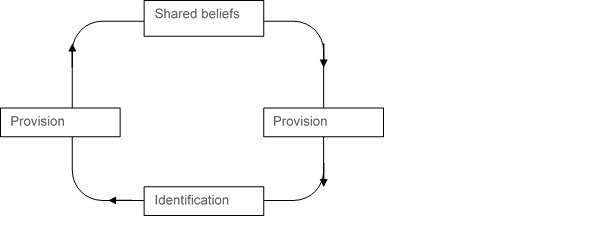

The model for reflection does not rely on a set definition of highly able young people; rather it examines beliefs, provision and identification in this very specific order. The model also builds on Freeman’s Sports Model in that it is a fluid and self-evaluating process. Through a five-step cyclical process, it asks people to reflect on their own personal beliefs and come to shared understandings of the concept in order to provide appropriate opportunities for identification and subsequent challenging provision. Rather than start with identification, it looks first at trying to establish the practical aspects of what a highly able pupil would be able to demonstrate and could be asked to do.

In this model, it is suggested that all educators would do well to clarify their beliefs about what constitutes a highly able learner (step one – shared beliefs). Only having discussed the relevant issues can provision be examined critically for the range and quality of opportunities available (step two - provision). These opportunities need to exist not only to teach those abilities deemed key to highly able learners across subject areas, but also to acknowledge those who are already able to display them in abundance (step three - identification). It is imperative, however, that we do not stop there. Further challenge for those who already display these abilities to a high level is required (step four - provision). This process may well make us redefine what we believe intelligent behaviours in particular subject areas to be (step five – shared beliefs).

(Smith and Dakers, 1998)

Points to consider

Strategies that are good for highly able pupils are good strategies for all pupils. By thinking about meeting the needs of highly able pupils, teachers can raise standards throughout the school.

Strategies that are good for highly able pupils are good strategies for all pupils. By thinking about meeting the needs of highly able pupils, teachers can raise standards throughout the school.

To meet the needs of all pupils, the class teacher may need to:

-set high expectations for the pupils;

-use a variety of forms of differentiation in their teaching;

-plan for the use of higher order learning/thinking skills in their teaching;

In particular they may need to:

-group highly able pupils together for specific subjects or activities;

-pace lessons to take account of the rapid progress of some highly able pupils;

-monitor and record the progress of highly able pupils;

-undertake lesson observations which monitor the progress and attainment of highly able pupils;

-give time for highly able pupils to extend or complete work if they need it;

-move highly able pupils into another class for some or all work, if their needs cannot be met in their chronological age class;

-set homework which is challenging for highly able pupils;

-be aware of school policy and practice for highly able pupils;

-consider early examination entry;

- liaise with staff from other educational settings for advice and resources eg Nursery staff speak with Primary school staff, Primary staff speak with Secondary School staff, Secondary staff speak with University staff/experts in the field.

Given that environmental factors can influence the development the emphasis in education must be on the learning environment. CfE places emphasis on the ‘how’ of learning and teaching. In addition, this approach builds on the work carried out in relation to Assessment is for Learning. It is essential that the learning environment and curriculum accommodates this wider and more individualistic view of learning. Curriculum for Excellence provides just such an opportunity and the seven principles on which it is built provide the vehicle to nurture such a view. Development of the curriculum, therefore, should involve from its inception:

-

challenge and enjoyment

-

personalisation and choice

-

breadth

-

depth

-

progression

-

coherence and

-

relevance

Example from a Primary School

Name - Gillian Jones, St Aidan’s Primary School, Wishaw, North Lanarkshire Council

|

What did you do?

|

Shared knowledge of high ability and SNAP with teaching staff during school in service. |

|

Why did you do it?

|

There was an existing strong focus on ‘closing the gap’ and supporting children falling behind in their learning (as there should be), there was however a need to develop teacher knowledge of providing challenge and understanding policy in this area. |

|

What was the impact? |

Our school has adapted its tracking and monitoring system to ensure that pupils are correctly identified and supported if considered highly able in a subject. This training has also helped our practitioners become aware of guidance and resources available from SNAP, also of current research in this area. Teachers and our school management feel more empowered when trying to support families who have a question about the pace and challenge of their child’s learning. Most importantly, our data from the Leuven Scale shows that our learners are being appropriately challenged and enjoying learning. |

|

|

The most valuable lesson has been that we must consider supporting highly able pupils in an inclusive way rather than extracting them from their classroom environment. The benefits of providing challenging and stimulating lessons are much greater when children of mixed ability are learning together. I have also enjoyed building upon my knowledge of Scottish educational policy linked to additional support for learning and helping other practitioners become aware of the support and resources available. |

|

What is the best piece of advice you would offer schools who are going to address the needs of the highly able?

|

It is important to think of highly able pupils in the same way as children who are identified as having a gap in their knowledge. Think inclusively and evaluate best practice already happening in the school. It doesn’t have to be something extra! |

Example from a Secondary School

Our Lady’s High School in Cumbernauld embarked on a programme to ensure that all learners, including highly able learners, were challenged and supported in school. The school were keen to embed practice within the curriculum and have developed an approach that is rooted in creative thinking, challenge and metacognition in classroom.

Our Lady's High School Cumbernaud - a secondary example

|

What did you do?

|

Embedded Creative thinking, challenge and metacognition into classroom dynamic. CPD offered to staff and NLC NQTs. IDL opportunities with Higher Order activities including research. |

|

Why did you do it?

|

Based on the actiotope model of high ability education (Albert, Zeigler http://ro.uow.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1525&context=sspapers ). I appreciate the importance of these when considering equity (challenge) adaptability (creative thinking) and lifelong learning (metacognition). |

|

What was the impact? |

Pace and challenge improved. |

|

What have you learned from your journey so far?

|

All highly able learners are different and have the same issues as any group of learners. Personalisation and mentoring are very important. |

|

What is the best piece of advice you would offer schools who are going to address the needs of the highly able? |

There are many ways to provide equity for highly able learners. CPD is very important and mentoring/ challenge opportunities with SNAP are very worthwhile for pupils. Classroom dynamic is very important and CfE pedagogy lends itself perfectly to providing well for highly able learners. |

Example from a School who provides ASL

Additional support for learning.

This setting supports learners with significant social, emotional and behavioural issues. Some of the highly able young people in this setting had previously experienced failure in academic settings. Altough they had capacity to succeed as learners, some did not engage in the learning process in ways that allowed them to demonstrate this. Staff in the school were keen to support all learners and recognised that challenging highly able learners required support and planning.

|

What did you do?

|

I created a VLE which allowed students to engage with resources, extra reading, documentaries and forums |

|

Why did you do it?

|

As in classes-some with SEBN-at times highly able students were either distracted, in a heightened state or completed their work ahead of their peers. It became clear that some didn’t want to engage or complete work due to peer pressure. |

|

What was the impact? |

One student in particular-in a SEBN setting, achieved national awards above the standard of his peers and has now gone off to study in college |

|

|

That as much work and care must go into teaching the highly able than any other students. Before starting the Masters at University of Glasgow, I was, perhaps, guilty of focussing my efforts on those who needed extra support to improve their levels, without providing further challenge to those who were excelling in their work. I have now reconsidered my pedagogy and approach. |

|

What is the best piece of advice you would offer schools who are going to address the needs of the highly able?

|

That the highly able should be treated as all other students in an inclusive classroom. That thorough planning on the part of the teacher-ideally together with the students-to create opportunities to allow all to be challenged, supported and achieve their potential. That ALL students must be supported in learning at THEIR OWN PACE. |

Example from an Education Authority

This is an example of how one Education Authority in Scotland, North Ayrshire, is considering how to embed learning and teaching approaches for highly able learners within their policies and practice.

North Ayrshire - an Education Authority example

|

What did you do?

|

I created a VLE which allowed students to engage with resources, extra reading, documentaries and forums |

|

Why did you do it?

|

As in classes-some with SEBN-at times highly able students were either distracted, in a heightened state or completed their work ahead of their peers. It became clear that some didn’t want to engage or complete work due to peer pressure. |

|

What was the impact? |

One student in particular-in a SEBN setting, achieved national awards above the standard of his peers and has now gone off to study in college |

|

|

That as much work and care must go into teaching the highly able than any other students. Before starting the Masters at University of Glasgow, I was, perhaps, guilty of focusing my efforts on those who needed extra support to improve their levels, without providing further challenge to those who were excelling in their work. I have now reconsidered my pedagogy and approach. |

|

What is the best piece of advice you would offer schools who are going to address the needs of the highly able?

|

That the highly able should be treated as all other students in an inclusive classroom. That thorough planning on the part of the teacher-ideally together with the students-to create opportunities to allow all to be challenged, supported and achieve their potential. That ALL students must be supported in learning at THEIR OWN PACE. |