Coinage of the Crusades:

Merging East and West

This virtual display highlights rare coins from The Hunterian collection which date back to the Crusades - a series of papally sanctioned military expeditions set against enemies of the Catholic faith. Struck in the crusader states, the coins reflect a range of influences as the monetary worlds of European, Islamic and Byzantine territories interacted across the Mediterranean.

Introduction

The Crusades were a series of papally sanctioned military expeditions set against enemies of the Catholic faith. In 1095, Pope Urban II launched a campaign to recapture Jerusalem from Muslim control and to aid the Byzantine Empire against Turkish invaders. Four years later, the armies of what became known as the First Crusade took Jerusalem from the Fatimids, who ruled Egypt.

The success of the First Crusade led to the establishment of four western-style states along and near the Levantine coast, consisting of the County of Edessa (modern-day Urfa in Turkey), the Principality of Antioch (modern-day Antakya in Turkey), the Kingdom of Jerusalem and the County of Tripoli (in modern-day Lebanon). Over the next few hundred years several other crusader territories were founded in Cyprus, Greece, Anatolia and the Aegean.

The coins that were struck in these lands reflect a range of influences as the monetary worlds of European, Islamic and Byzantine states interacted across the Mediterranean. Coins were primarily used as a means of legal tender or exchange, but they also acted as expressions of power and symbols of authority. They supplied the ruling class with a unique way of expressing themselves and we can learn much about how they wanted to be seen by others and how they interacted with their subjects. This was especially important for the rulers of the crusader states who ruled over diverse populations including European settlers and native Muslims, Christians and Jews. In order to assert and express their authority over all their subjects, they merged coinage patterns found in Europe with those found in the Eastern Mediterranean.

Coins in the Crusader States

Frankish settlers began minting coins soon after the First Crusade and continued to do so for several hundred years. The coins from the crusader states that survive show just how much the new rulers relied on already-existing commercial and economic systems.

People in the medieval Middle East made much more extensive use of money than people did in medieval Europe at the time. Whereas coinage in western Europe in the 1000s and 1100s was primarily silver-based (this changed in the late 1200s), coins in the eastern Mediterranean were based on a variety of metals, with gold coins being the most valuable. When the crusaders took over lands in this part of the world, they settled on a hybrid system of currency which included imitations of local Arabic or Byzantine copper, silver and gold coins with western iconographic modifications, and silver coins from western Europe. Over time, new coins were developed and these varied across the different states.

The Kingdom of Jerusalem

After a three-year expedition, the armies of the First Crusade conquered Jerusalem on 15 July 1099. Godfrey of Bouillon, one of the leaders of the First Crusade, became the first ruler of the new Latin kingdom.

After a three-year expedition, the armies of the First Crusade conquered Jerusalem on 15 July 1099. Godfrey of Bouillon, one of the leaders of the First Crusade, became the first ruler of the new Latin kingdom.

The earliest coins found in circulation in the Kingdom of Jerusalem were different from those found in the other crusader states in that they, by and large, were not based on copper and were instead either imports from northern Italy and southern France, or of local provenance, for example Islamic gold dinars from Fatimid Egypt.

The new rulers began minting gold and silver coins in the 1140s. The gold coins (Saracen bezants) were essentially copies of the gold Fatimid dinars; they even retained the Arabic Koranic inscriptions. The decision to imitate the Islamic design suggests that the Latin rulers felt no need to alter the estab lished high-value coinage. Saracen bezants were made in two standards. Those of higher quality were minted before 1187 – when much of the crusader states were lost to Saladin, sultan of Egypt and Syria – and they seem to have been in use until the 1250s. Pope Innocent IV eventually banned the coins and their design (which until then still bore Islamic inscriptions) was changed to include Christian symbols and text. Against the pope’s objections, however, the text on the new Christian design was still written in Arabic.

lished high-value coinage. Saracen bezants were made in two standards. Those of higher quality were minted before 1187 – when much of the crusader states were lost to Saladin, sultan of Egypt and Syria – and they seem to have been in use until the 1250s. Pope Innocent IV eventually banned the coins and their design (which until then still bore Islamic inscriptions) was changed to include Christian symbols and text. Against the pope’s objections, however, the text on the new Christian design was still written in Arabic.

The main silver and billon (silver alloy) coins of the kingdom were of a European design and were struck in two series. This type of coinage was rare in the eastern Mediterranean in the first half of the 1100s, and its appearance shows that western currencies and designs moved into the region. Coins from the first series, minted in the 1140s during the reign of King Baldwin III, feature the Tower of David on the reverse.  In the 1160s, during King Amalric’s reign, these were replaced by a second series of coins, which depict the church of the Holy Sepulchre on their reverse.

In the 1160s, during King Amalric’s reign, these were replaced by a second series of coins, which depict the church of the Holy Sepulchre on their reverse.

The adoption of these buildings on coins was a deliberate and considered decision. The use of the buildings functioned as way of demonstrating and increasing the prestige of the kings of Jerusalem while also legitimising their rule. The Tower of David, for instance, was one of the key defensive and administrative buildings in Jerusalem and was associated with the biblical King David. The Holy Sepulchre, on the other hand, had become closely linked to the crusading movement and was the site where the rulers of Jerusalem were crowned and buried.

While in the Kingdom of Jerusalem the right to strike coinage was a royal prerogative, some local lords took advantage of the weakened monarchy after Saladin’s conquests and produced their own coins after 1187. Other lords issued lead tokens, which people may have used as petty cash to pay tradesmen and labourers, or as gambling money.

While in the Kingdom of Jerusalem the right to strike coinage was a royal prerogative, some local lords took advantage of the weakened monarchy after Saladin’s conquests and produced their own coins after 1187. Other lords issued lead tokens, which people may have used as petty cash to pay tradesmen and labourers, or as gambling money.

Images

Ali az-Zahir, Fatimid Caliph, dinar, c.1027 – 1029, gold, Egypt, GLAHM:39297, Jackson.

Saracen bezant, c.1148 – 1187, gold, Kingdom of Jerusalem, GLAHM:46629, McFarlan.

Baldwin III, king of Jerusalem, billon denier, 1143 – 1163, silver alloy, Kingdom of Jerusalem, GLAHM:39477, McFarlan.

Amalric and successors, kings of Jerusalem, billon denier, 1163 – c.1235, silver alloy, Kingdom of Jerusalem, GLAHM:39476, McFarlan.

The County of Edessa

The County of Edessa (modern-day Urfa in Turkey) was the first crusader state to come into existence, having been established in 1098, while the First Crusade was still under way, by a younger brother of Godfrey of Bouillon, Baldwin of Boulogne. It was also the first to disappear, following its conquest by Imad al-Din Zengi, the Turkish ruler of Mosul, in 1144.

The County of Edessa (modern-day Urfa in Turkey) was the first crusader state to come into existence, having been established in 1098, while the First Crusade was still under way, by a younger brother of Godfrey of Bouillon, Baldwin of Boulogne. It was also the first to disappear, following its conquest by Imad al-Din Zengi, the Turkish ruler of Mosul, in 1144.

The monetary affairs of the County of Edessa were not as varied as the other Frankish states in the East, mainly because it did not survive for long. Rather than looking to Egypt for inspiration, the new rulers’ coinage adopted a Byzantine model, thus acknowledging Byzantium’s still significant cultural and political influence in the region. The earliest surviving coins minted under Frankish rule are imitations of Byzantine copper coins and include the name BAΔT (Baldwin) in Greek. It is difficult to tell if these were issued by Baldwin of Boulogne or his successor Baldwin II, as Baldwin of Boulogne’s reign as count of Edessa came to a swift end when he was crowned king of Jerusalem in 1100.

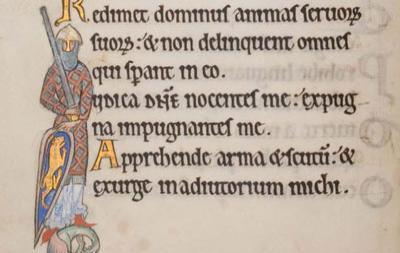

The iconography on some of the coins minted from c.1110 onwards is remarkable. Some depict the count as a knight, wearing a conical helmet and mail armour, and holding a raised sword and kite-shaped shield. On later coins the shield has been replaced by a cross, and in some cases the raised sword had given way to a sheathed sword. This new iconography no longer had anything to do with Byzantine designs and instead suggests that the counts had developed a unique identity of their own. The shift also shows how coins could be used as propaganda tools to communicate political and religious messages. The count is depicted as a defender of his lands and the Christian faith. The legend on the coin reads: BAΔT ΔOINOC ΔOVΛO CTAY (Baldwin, the servant of the Cross).

The iconography on some of the coins minted from c.1110 onwards is remarkable. Some depict the count as a knight, wearing a conical helmet and mail armour, and holding a raised sword and kite-shaped shield. On later coins the shield has been replaced by a cross, and in some cases the raised sword had given way to a sheathed sword. This new iconography no longer had anything to do with Byzantine designs and instead suggests that the counts had developed a unique identity of their own. The shift also shows how coins could be used as propaganda tools to communicate political and religious messages. The count is depicted as a defender of his lands and the Christian faith. The legend on the coin reads: BAΔT ΔOINOC ΔOVΛO CTAY (Baldwin, the servant of the Cross).

Images

Baldwin II, count of Edessa, folles, c.1110 – 1118, copper, Edessa, GLAHM:46281, McFarlan.

A crusader wearing a conical nasal helmet and mail armour, and holding a raised sword and kite-shaped shield.

The Hunterian Psalter, England, c.1170. Glas. Uni. Sp. Coll. MS Hunter U.3.2 (229), fol. 54v.

The Principality of Antioch

The Principality of Antioch was the second of the crusader settlements to be founded while the First Crusade was under way. The city of Antioch (modern-day Antakya in Turkey) fell to the crusading army in 1098 after a difficult eight-month siege in the course of the First Crusade. Bohemond of Taranto, an Italian-Norman commander, played a key part in the city’s capture and was given command of the city. He became the first prince of Antioch and established the new crusader principality.

Like the County of Edessa, the initial coinage of the Principality of Antioch was marked by the minting of quasi-Byzantine copper coinage. The inscriptions were in either Greek or Latin. These coins featured the image of St Peter, patron saint and first patriarch of Antioch, on the obverse (front). The design was either locally inspired or had been introduced by Norman crusaders from southern Italy, where similar designs were already in use.  Bohemond’s successors continued to strike new copper coins until around 1130. One, minted during the regency of his nephew Tancred, shows a bearded Tancred holding a sword and wearing a headpiece resembling a turban on the obverse.

Bohemond’s successors continued to strike new copper coins until around 1130. One, minted during the regency of his nephew Tancred, shows a bearded Tancred holding a sword and wearing a headpiece resembling a turban on the obverse.

The princes of Antioch seem to have moved away from the Byzantine-style copper designs in the 1140s, when we see an increase in western-style silver deniers (pennies). These came in different styles, with the so-called ‘helmet’ deniers, minted from the 1160s, being the most plentiful. Here the prince is depicted in typical contemporary armour including a conical nasal helmet decorated with a cross and a chain-mail coif, which protects the neck.

Images

Bohemond III, prince of Antioch, billon denier, 1149 – c.1163, silver alloy, Antioch, GLAHM:39475, McFarlan.

Bohemond III, prince of Antioch, billon denier, 1163 – 1188, silver alloy, Antioch, GLAHM:39445, McFarlan.

The County of Tripoli

The County of Tripoli (in modern-day Lebanon) was the last crusader state to be established on the Levantine coast. Although Count Raymond IV of Toulouse, one of the leaders of the First Crusade, had set his sights on Tripoli as early as 1102, it was not until 1109 (four years after Raymond’s death) that his son Bertram finally managed to take the city and make it the centre of a new county, which lasted until 1289.

The County of Tripoli (in modern-day Lebanon) was the last crusader state to be established on the Levantine coast. Although Count Raymond IV of Toulouse, one of the leaders of the First Crusade, had set his sights on Tripoli as early as 1102, it was not until 1109 (four years after Raymond’s death) that his son Bertram finally managed to take the city and make it the centre of a new county, which lasted until 1289.

The coinage of the County of Tripoli consists primarily of the same gold bezants, billon deniers and coppers also found in the other crusader states. Interestingly, Tripoli seems to have been the first crusader territory to issue billon deniers in the European style. Some early (and rare) examples can be dated to around 1109-1112. Deniers, of different design, appear again in the 1140s. The most elaborate ones feature a ‘star and crescent’ (or sun and moon) on the reverse.

In the 1140s we also see the appearance of Saracen bezants and copper coins. The earliest copper coins were produced sometime between 1137-1152 and feature crosses or the Agnus Dei (Lamb of God). The design of the Agnus Dei coins emulated the design of coins from the counts of Tripoli’s ancestral home of Toulouse. Other, later, variants depicted the same ‘star and crescent’ imagery also found on some of the deniers or a castle.

In the 1140s we also see the appearance of Saracen bezants and copper coins. The earliest copper coins were produced sometime between 1137-1152 and feature crosses or the Agnus Dei (Lamb of God). The design of the Agnus Dei coins emulated the design of coins from the counts of Tripoli’s ancestral home of Toulouse. Other, later, variants depicted the same ‘star and crescent’ imagery also found on some of the deniers or a castle.

Like the Saracen bezants associated with the Kingdom of Jerusalem, the bezants associated with the County of Tripoli were of two standards, with the better ones pre-dating 1187. But Tripoli’s Saracen bezants differed from those of Jerusalem in that their design was based on a different prototype. At some point after 1187, the letters B and T were added to the coins. The first letter may stand for the name of the counts of Tripoli (who were all called Bohemond between 1187 and 1287) and the second for Tripoli.  Their design was subject to similar changes as those of the Jerusalem bezants following the papacy’s complaints in the 1250s.

Their design was subject to similar changes as those of the Jerusalem bezants following the papacy’s complaints in the 1250s.

Not long before the County of Tripoli’s collapse in 1289, the counts had issued a new type of silver coin, the gros. The gros tournois first appeared in France in 1266, during the reign of King Louis IX. Its introduction to Tripoli demonstrates a profound change in the county’s monetary policy. The new coin came in two types. The first features an elaborate ‘star’ design and the second has a three-towered castle on the reverse. The later ones were the last coins to be minted anywhere in the mainland crusader states. The gros shown features a hole below the M in the legend, suggesting that it was reused as jewellery.

Images

Raymond II/III, counts of Tripoli, billon denier, late 1140s – c.1164, silver alloy, Tripoli, GLAHM:39472, McFarlan.

Raymond III, count of Tripoli, copper, c.1173/4 – c.1187, copper, Tripoli, GLAHM:39474, McFarlan.

Bohemond VI/VII, counts of Tripoli, gros, c.1268 – 1289, silver, Tripoli, GLAHM:39473, McFarlan.

The Kingdom of Cyprus

In 1191, on his way to the Holy Land, Richard the Lionheart, king of England, conquered Cyprus from the Byzantine Empire and sold it first to the Knights Templar, who were unable to control it, and then to Guy of Lusignan, the former king of Jerusalem, who had lost his kingdom to Saladin in 1187. Guy and his descendants would rule the Kingdom of Cyprus for the next three centuries.

In 1191, on his way to the Holy Land, Richard the Lionheart, king of England, conquered Cyprus from the Byzantine Empire and sold it first to the Knights Templar, who were unable to control it, and then to Guy of Lusignan, the former king of Jerusalem, who had lost his kingdom to Saladin in 1187. Guy and his descendants would rule the Kingdom of Cyprus for the next three centuries.

The standard coin in Cyprus at the time of Richard’s conquest was a debased concave gold coin that was completely Byzantine in style. These coins are known as white bezants. None exist in The Hunterian’s numismatic collection, but they are very similar to the gold bezant shown here. The Lusignans issued imitations of these coins until the end of the 1200s. They tend to feature an image of Christ enthroned on the obverse and an image of the king in Byzantine-style costume holding a globus cruciger (cross-bearing orb) and a staff headed with a cross on the reverse.

Until the late 1200s, the lower value coins in use on Cyprus were mostly billon deniers like those produced in the mainland crusader states. Introduced by Guy of Lusignan, they feature a crowned bust of the king on the obverse and an image of the Holy Sepulchre on the reverse. The legend reads REX GVIDO; EIERVSALEM (Guy, king of Jerusalem). Other billon deniers and white bezants issued by the Lusignan dynasty of Cyprus feature similar legends. The legend suggests that they were minted in Jerusalem when in fact they were struck in Cyprus. The use of the title ‘king of Jerusalem’ shows that long after the loss of the Holy City the kings of Cyprus held on to their claim to the Kingdom of Jerusalem. Some copper coins were minted alongside the deniers, but they are extremely rare.

Near the end of the 1200s, the kings of Cyprus replaced the white bezants with a new silver coinage, the gros, which came in two denominations: the gros grand, worth half of the value of a white bezant, and the gros petit, worth a quarter of the value of a white bezant. The gros was, again, inspired by the French gros tournois. Interestingly, the imagery featured on the gros of the kings of Cyprus is rendered in the western style while the concentric circles on the original gros tournois were possibly inspired by Saracen bezants, with which King Louis IX would have come into contact during his ill-fated crusade of 1248-1254.

Near the end of the 1200s, the kings of Cyprus replaced the white bezants with a new silver coinage, the gros, which came in two denominations: the gros grand, worth half of the value of a white bezant, and the gros petit, worth a quarter of the value of a white bezant. The gros was, again, inspired by the French gros tournois. Interestingly, the imagery featured on the gros of the kings of Cyprus is rendered in the western style while the concentric circles on the original gros tournois were possibly inspired by Saracen bezants, with which King Louis IX would have come into contact during his ill-fated crusade of 1248-1254.

Images

Alexius III, Byzantine Emperor, hyperpyron, 1195 – 1203, gold, Constantinople, GLAHM:46559, McFarlan.

Peter I, king of Cyprus, gros, 1359 – 1369, silver, Cyprus, GLAHM:46218, McFarlan.

Philip IV, king of France, gros tournois, c.1290 – 1295, silver, France, GLAHM:39444, Hunter.

The Latin Empire and Frankish Greece

In 1202, a crusading army set out to recapture Muslim-controlled Jerusalem by first conquering Egypt. However, due to a series of political and economic events, the crusading army ended up seizing Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul) in 1204, which fractured the Byzantine Empire. The crusaders divided large tracts of the empire into several new crusader states in Anatolia and Greece. The largest were the Latin Empire, centred on Constantinople, the Kingdom of Thessalonica, the Principality of Achaia, the Duchy of Athens, and the Duchy of the Archipelago.

In 1202, a crusading army set out to recapture Muslim-controlled Jerusalem by first conquering Egypt. However, due to a series of political and economic events, the crusading army ended up seizing Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul) in 1204, which fractured the Byzantine Empire. The crusaders divided large tracts of the empire into several new crusader states in Anatolia and Greece. The largest were the Latin Empire, centred on Constantinople, the Kingdom of Thessalonica, the Principality of Achaia, the Duchy of Athens, and the Duchy of the Archipelago.

The initial tendency of these new states was to imitate the Byzantine coins that were already in circulation. The Latin Empire issued such coins throughout its brief history (1204-1261). Coins were also imported from Europe, and from the middle of the 1200s the rulers of the crusader states in Greece began to mint their own coins, first in copper and later in billon. The most common were the denier tournois, a coin which originated in France. Those produced in Greece are indistinguishable in design from those in France, featuring a cross on the obverse and a castle on the reverse. The only difference is their legends. Denier tournois were minted in large numbers and by 1300 they had become the dominant currency in mainland Greece.

Image

Guy II, duke of Athens, denier tournois, 1287 – 1308, silver alloy, Greece, GLAHM:39478, McFarlan.

Further Reading

For the most comprehensive work on the coinage of the crusader states in the Latin East see, David M. Metcalf, Coinage of the Crusades and the Latin East in the Ashmolean Museum Oxford (London, 1995).

A good overview of the crusading movement is Jonathan Riley-Smith, The Crusades: A History (London, third edition, 2014). For a study of the Crusades with a focus on materiality (including coins) see, Christopher Tyerman, The World of the Crusades (New Haven and London, 2019).

More focused studies on the coinage of the crusader states in the Latin East can be found in The Numismatic Chronicle. For example, if you wanted to explore the use of Fatimid dinars in the crusader states in more depth, you could read Oren Tal, Robert Kool and Issa Baidoun, ‘A Hoard Twice Buried? Fatimid Gold from Thirteenth Century Crusader Arsur (Apollonia-Arsuf)’, The Numismatic Chronicle (1966-), 173 (2013), 261-292. Or, if you are interested in the billon and copper coins of the County of Tripoli, a good place to start would be C. J. Sabine, ‘The Billon and Copper Coinage of the Crusader County of Tripoli, c. 1102 – 1268’ The Numismatic Chronicle (1966-), 20:140 (1980), 71-112. The journal is available online through Jstor.

Acknowledgements

James Gallacher, Doctoral Research Candidate, University of Glasgow

Dr Jochen Schenk, Lecturer in Medieval Transcultural History, University of Glasgow

Staff of The Hunterian, in particular Chris MacLure and Harriet Gaston