When two thirds of a million books moved home

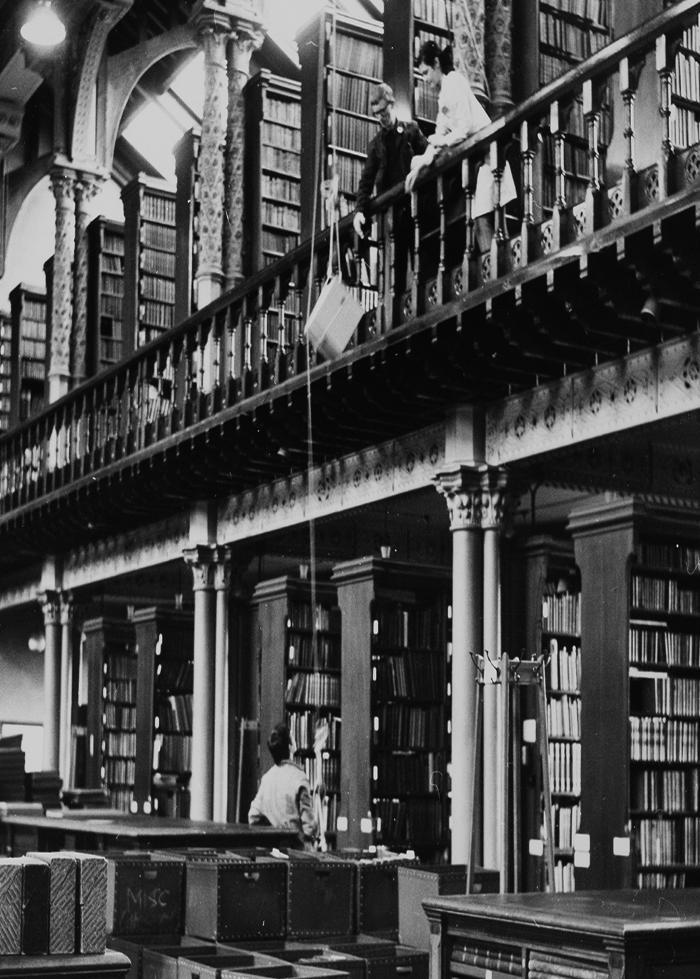

"Student workers, along with a rather harassed library staff, are excavating the 750,000 [sic] or so volumes which have accumulated in cathedral-like splendour in the 98 years since Sir George Gilbert Scott perched his new university building atop Gilmorehill. GLASGOW HERALD, 16 AUGUST 1968"

The iconic tower of the Gilbert Scott Building may be the first image that comes to mind when the University is mentioned, but at the intellectual heart of any university is its library, and Glasgow is no exception. It is 50 years since our striking main library took up position at the top of Hillhead Street.

A new library building had been urgently needed for many years. By the late 1950s, there were 81 separate subject and departmental libraries scattered around the University, many of which had serious space problems, and the main library was housed over six cramped, warren-like floors off the West Quad. A prominent site at the centre of the campus was selected for its replacement, and because of the restricted ground space available, the new building had to be high-rise.

The vision

Lynchpin of the plan was (Robert) Ogilvie MacKenna, who held the post of University Librarian from 1951 to 1978 and had ideas ahead of his time for progressing library services. Stressing the need to bring books and readers together, with staff as facilitators, he noted in his brief to the architect, William Whitfield, that “the library is to be thought of not as a storehouse for books, but as a workshop for readers using books.”

Changed days

This was a different era. A junior library assistant of the late 1960s took home a salary of £385 per year, rising by £25 after five years’ service. The library had three separate manual cataloguing systems. And freshers arriving in 2018 may find it hard to believe that until 1968, first-years were denied direct access to the books in the library, the “stacks”, but were restricted to ordering them through the catalogue and picking them up at the issue desk.

Things needed to change. Ogilvie MacKenna had the foresight to commission a new building that was adaptable and capable of further extension, and the move was planned meticulously.

Many library staff were diverted from their usual responsibilities in the months leading up to the move in order to work on tasks such as measuring shelving and allocating subjects to each floor of the new building.

Inez McIntyre (MA 1960) worked on the issue desk in the old library, and remembers the human traffic jams that prevailed just before closure. “Teaching staff were permitted to borrow far more than their usual quota, and did, in their thousands, standing four deep at the desk what seemed like all day, every day.”

Painstaking preparation

640,000 books had to be moved. The first book on each shelf had a marker placed in it, with a code showing its precise location in the new building, and on Monday 8 July 1968 the removal work began. In a letter to staff just before it all started, Ogilvie MacKenna warned them good-naturedly that there would be arduous tasks ahead, but that everybody needed to do their bit. “In technical terms,” he said, “it’s called mucking in.”

Those who were given the job of packing boxes and carrying them through the narrow galleries, with the low girders padded to reduce head injuries, became known as “trundlers”, and spent their summer vacation carrying out repetitive, strenuous tasks with patience and good humour.

Hitches and setbacks were common that summer. The installation of lifts in the new building was delayed due to the contractors working simultaneously on the Queen Elizabeth 2 liner at Greenock. And at one point, one of the removal vans turned up in Troon for use in a “flitting” (house move), accidentally full to overflowing with several thousand academic volumes.

“Uncertainties of one kind or another seemed to hover continuously over the entire operation,” says John Cooper, director of removal operations in the new building. “It seemed always just a matter of trying to adjust to a continually shifting pattern of events, including not usually knowing, until it actually arrived, which of the available entrances each shipment was going to arrive at.”

Plans become reality

When the new building opened on 30 September 1968 there was no fanfare or ribbon-cutting, but just a relieved feeling of finally being able to get on with the job, though staff who had got used to using walkie-talkies to communicate during the move did find themselves saying “Over!” in the middle of normal telephone conversations for some time afterwards.

The new building came with innovations such as subject-specialist staff, a photographic department, microfilm readers and, uniquely, a bindery on the premises, as well as the radical change, finally, of allowing first-years to browse the stacks directly.

Learn more

The key players

Moving the library was a huge undertaking that involved many people. Read about three people with varied roles who were instrumental to the success of the operation.

The visionary

Robert Ogilvie MacKenna (MA 1934) was the far-sighted University Librarian who was planning the building he knew the University urgently needed for almost two decades before it became a reality. He held the post from 1951 to 1978, having initially joined the library in 1936 before war service and library experience elsewhere. Well-liked and respected by his staff, he is remembered as a modest and self-deprecating man. He once said that the only reason he’d managed to achieve a First for his degree in Classics was that the weather had been too bad to play cricket, so he’d had no alternative but to stay inside studying. Over his 26 years as Librarian, more than a dozen of his staff members were encouraged to take up senior posts at other libraries, forming a diaspora of Glasgow librarians in places as far-flung as Canada and Australia; his deputy during the 1968 move, John Simpson, became founding librarian of the Open University. He was passionate about uniting readers with books in the most accessible ways possible, and succeeded in increasing the library membership sixfold, to over 16,000, by the time he retired.

Robert Ogilvie MacKenna (MA 1934) was the far-sighted University Librarian who was planning the building he knew the University urgently needed for almost two decades before it became a reality. He held the post from 1951 to 1978, having initially joined the library in 1936 before war service and library experience elsewhere. Well-liked and respected by his staff, he is remembered as a modest and self-deprecating man. He once said that the only reason he’d managed to achieve a First for his degree in Classics was that the weather had been too bad to play cricket, so he’d had no alternative but to stay inside studying. Over his 26 years as Librarian, more than a dozen of his staff members were encouraged to take up senior posts at other libraries, forming a diaspora of Glasgow librarians in places as far-flung as Canada and Australia; his deputy during the 1968 move, John Simpson, became founding librarian of the Open University. He was passionate about uniting readers with books in the most accessible ways possible, and succeeded in increasing the library membership sixfold, to over 16,000, by the time he retired.

The planner

Peter Asplin, who still volunteers in the library 50 years later, was tasked with the detailed planning and execution of the move in 1968. He was fortunate to have the experience of Edinburgh University making a similar library move the previous year to draw on. “The only feasible access for a speedy operation was at the South Front,” he says, “with books being extracted via the cloisters, or the Bute Hall and Senate lift.” Accordingly, a wooden ramp and canvas awning were installed at the foot of the tower. Preparation of shelves in the new building could not be done until the last minute, and the Hillhead Street main entrance had to be redesigned after planning permission to close the street to traffic was refused. “Building work promised for completion in March 1968 was well behind schedule,” Peter remembers, “and Mr MacKenna spent the summer pursuing contractors to get the building fit for public use by October. However, we were lucky to have an unusually dry summer to carry out the work, and temporary covers for boxes being unloaded in the rain were needed on very few occasions.”

Peter Asplin, who still volunteers in the library 50 years later, was tasked with the detailed planning and execution of the move in 1968. He was fortunate to have the experience of Edinburgh University making a similar library move the previous year to draw on. “The only feasible access for a speedy operation was at the South Front,” he says, “with books being extracted via the cloisters, or the Bute Hall and Senate lift.” Accordingly, a wooden ramp and canvas awning were installed at the foot of the tower. Preparation of shelves in the new building could not be done until the last minute, and the Hillhead Street main entrance had to be redesigned after planning permission to close the street to traffic was refused. “Building work promised for completion in March 1968 was well behind schedule,” Peter remembers, “and Mr MacKenna spent the summer pursuing contractors to get the building fit for public use by October. However, we were lucky to have an unusually dry summer to carry out the work, and temporary covers for boxes being unloaded in the rain were needed on very few occasions.”

The trundler

William Henderson (MA 1968) had just graduated and needed a summer job to fill in time and provide an income before going to work as an Overseas Institute/Nuffield Fellow in Botswana. “The work, as you might imagine, was extremely tedious but the team of young men who ‘trundled’ worked with great humour,” he recalls. “Each morning we were allocated a section of the library to clear. The boxes were passed down a series of slides, lifted on to trolleys and ‘trundled’ through the cloisters and then, with a quick rush at the end, up a steep slope and on to a waiting van. Of course, it was a case of brute labour and that little rush at the end became progressively harder as the day progressed.”

William Henderson (MA 1968) had just graduated and needed a summer job to fill in time and provide an income before going to work as an Overseas Institute/Nuffield Fellow in Botswana. “The work, as you might imagine, was extremely tedious but the team of young men who ‘trundled’ worked with great humour,” he recalls. “Each morning we were allocated a section of the library to clear. The boxes were passed down a series of slides, lifted on to trolleys and ‘trundled’ through the cloisters and then, with a quick rush at the end, up a steep slope and on to a waiting van. Of course, it was a case of brute labour and that little rush at the end became progressively harder as the day progressed.”

This article was first published in December 2018.