Scottish scientists play a key part in new ‘comprehensive’ map of cancer genomes

Published: 5 February 2020

A collaborative global scientific effort, which includes a group of researchers from UofG, has completed the most comprehensive study of whole cancer genomes to date

A collaborative global scientific effort, which includes a group of researchers from the University of Glasgow, has completed the most comprehensive study of whole cancer genomes to date. The work will significantly improve our fundamental understanding of cancer, signposting new directions for its diagnosis and treatment.

The Pan-Cancer Analysis of Whole Genomes Project (PCAWG), or the Pan-Cancer Project, has discovered causes of previously unexplained cancers, pinpointed cancer-causing events and zeroed in on mechanisms of development.

The results from the Pan-Cancer Project appear in 23 peer-reviewed scientific papers, published simultaneously today in Nature and its affiliated journals.

The Pan-Cancer Project was developed by the International Cancer Genome Consortium (ICGC), which is headquartered at the University of Glasgow’s Wolfson Wohl Cancer Research Centre, and is led by Professor Andrew Biankin, Regius Professor of Surgery at the University and Executive Director of ICGC.

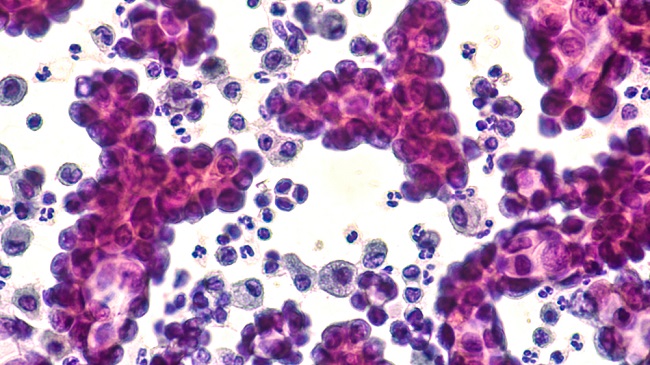

The ICGC Pan-Cancer Project – a collaboration involving more than 1,300 scientists and clinicians from 37 countries – analysed more than 2,600 genomes of 38 different tumour types, creating a huge resource of primary cancer genomes. This was then used as the launch-point for 16 working groups studying multiple aspects of cancer’s development, causation, progression and classification.

University of Glasgow scientists contributed data to the projects, playing key roles in various working groups within the Pan-Cancer Project, particularly how this knowledge may impact on cancer treatment and outcomes. Their contribution formed the foundation for the ICGC’s new initiative ARGO, which aims to take the next step.

Previous studies focused on the 1 per cent of the genome that codes for proteins, analogous to mapping the coasts of the continents. The Pan-Cancer Project explored, in considerably greater detail, the remaining 99 per cent of the genome, including key regions that control switching genes on and off – analogous to mapping the interiors of continents versus just their coastlines.

The Pan-Cancer Project has made available a comprehensive resource for cancer genomics research, including the raw genome sequencing data, software for cancer genome analysis, and multiple interactive websites exploring various aspects of the Pan-Cancer Project data.

The Pan-Cancer Project extended and advanced methods for analysing cancer genomes which included cloud computing, and by applying these methods to its large dataset, discovered new knowledge about cancer biology and confirmed important findings of previous studies. In the 23 papers published today in Nature and its affiliated journals, the Pan-Cancer Project reports that:

- The cancer genome is finite and knowable, but enormously complicated. By combining sequencing of the whole cancer genome with a suite of analysis tools, we can characterise every genetic change found in a cancer, all the processes that have generated those mutations, and even the order of key events during a cancer’s life history.

- We are close to cataloguing all of the biological pathways involved in cancer and having a fuller picture of their actions in the genome. At least one causal mutation was found in virtually all of the cancers analysed and the processes that generate mutations were found to be hugely diverse -- from changes in single DNA letters to the reorganization of whole chromosomes. More than a dozen regions of the genome controlling how genes switch on and off were identified as targets of cancer-causing mutations.

- Through a new method of “carbon dating”, Pan-Cancer discovered that we can identify mutations which occurred years, sometimes even decades, before the tumour appears. This opens, theoretically, a window of opportunity for early cancer detection.

- Tumour types can be identified accurately according to the patterns of genetic changes seen throughout the genome, potentially aiding the diagnosis of a patient’s cancer where conventional clinical tests could not identify its type. Knowledge of the exact tumour type could also help tailor treatments.

Professor Andrew Biankin said: “I am immensely proud that our interdisciplinary team of scientists here at the University of Glasgow played a key part in this important milestone of cancer research.

“These 23 research papers, which will be followed by yet more research from the project, will significantly improve our understanding of cancer and, in time, improve patient outcomes.

“ICGC’s latest initiative called ARGO (Accelerating Research in Genomic Oncology) is about the patient, with the goal of delivering to the world a million patient-years of precision oncology knowledge to improve human health. We must ensure that this data is shared across traditional jurisdictional boundaries to realise the full impact of precision medicine, for the benefit of all.”

Dr. Lincoln Stein, member of the project steering committee and Head of Adaptive Oncology at the Ontario Institute for Cancer Research (OICR), said: “The findings we have shared with the world today are the culmination of an unparalleled, decade-long collaboration that explored the entire cancer genome.

“With the knowledge we have gained about the origins and evolution of tumours, we can develop new tools and therapies to detect cancer earlier, develop more targeted therapies and treat patients more successfully.”

Dr. Peter Campbell, member of the Pan-Cancer Project steering committee and Head of Cancer, Ageing and Somatic Mutation at the Wellcome Sanger Institute in the UK, said: “This work is helping to answer a long-standing medical difficulty, why two patients with what appear to be the same cancer can have very different outcomes to the same drug treatment. We show that the reasons for these different behaviours are written in the DNA. The genome of each patient’s cancer is unique, but there are a finite set of recurring patterns, so with large enough studies we can identify all these patterns to optimize diagnosis and treatment.”

Enquiries: ali.howard@glasgow.ac.uk or elizabeth.mcmeekin@glasgow.ac.uk / 0141 330 6557 or 0141 330 4831

First published: 5 February 2020

<< Medicine