Doing and Studying Pilgrimage

Published: 1 December 2014

Dr Nicole Bourque writes about her experiences of ‘doing and studying pilgrimage’.

At a recent international conference on pilgrimage at the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia, I was asked how I had become interested in pilgrimage. My answer surprised them: ‘It was because of one of my students’. The story of my journey into doing and studying pilgrimage is a good example of the ‘critical, reflexive and engaged’ anthropology (or sociology) that happens at the University of Glasgow.

After a lecture on pilgrimage for an Honours level course on the anthropology of religion, a student approached me and said that she had enjoyed learning about theories of pilgrimage, but that they didn’t match up to her own experience of doing the Camino de Santiago the previous summer. The lecture focused on Turner’s (1969) and Turner and Turner’s (1978) classic works on pilgrimage and the criticisms of this. The Turners note that people starting on pilgrimage are separated from their daily lives and social status and enter a liminal (i.e. betwixt and between) state. In this state, the normal social structures which affect their daily lives are not relevant (anti-structure) and close bonds are created between the people sharing this experience (communitas). After pilgrimage, people return to their daily life (reagregation) and normal social status (structure). This model of the social changes experienced during pilgrimage became very influential in anthropology and was used to analyse pilgrimages in various societies, including the Muslim pilgrimage of Hajj.

This portrayal of communitas and anti-structure was famously challenged by Michael Sallnow in Pilgrims of the Andes (1987). I read this book as an undergraduate and it influenced my decision to do PhD research on religion in the Andes (but on syncretism rather than pilgrimage). Sallnow noted that viewing pilgrimage through the lens of communitas and anti-structure blinded the researcher to instances where there were clear divisions between pilgrims and where ‘normal’ social status was reinforced. This debate, which is critically evaluated by Coleman (2002), became a key feature in the anthropological analysis of pilgrimages in number of societies.

The student who approached me after the lecture said that she could see examples which supported both sides of the debate in her own experience of pilgrimage, but that the really interesting thing she noted were the various motivations people had for doing the pilgrimage, how people reshaped their identities and the physical experience of doing the pilgrimage. I suggested that this would be an excellent honours dissertation project. She received a Carnegie Vacation scholarship to do the pilgrimage again during the summer. It was an excellent dissertation and it inspired me to do the pilgrimage myself, not as a research project (I was involved with a different project at the time), but as an experience.

So, in the summer of 2008, I set forth on foot from St Jean de Pied de Port in the French Pyrenees and, along with hundreds of other people with backpacks and walking poles, started on the French Route (el Camino Frances) to Santiago de Compostela. This route goes over the Pyrenees and through Pamplona, Logrono in the Rioja region, Burgos, Leon, Astorga and into Galicia in north-west Spain. After 30 days and 820km, I arrived in Santiago de Compostella.

Day 2 - Sign at Roncesvalles. Photo by author.

While I did not set off with the intention of researching the Camino de Santiago, the anthropologist within me never did switch off and I paid attention to issues of communitas, anti-structure, motivations, identity and embodiment.

The pilgrimage to Santiago to visit the bones of St. James (Santiago) dates from medieval times and was, along with Rome and Jerusalem, a major site of pilgrimage. It’s popularity waned over time but was revived in 1982 when Pope John Paul II encouraged pilgrimage. The numbers of pilgrims have increased dramatically ever since. In 1985, the Pilgrims’ Office in Santiago recorded 1245 pilgrims. In 2010, there were 272, 703. There has been an explosion of literature on the Camino in the form of guide books and personal accounts. In 2010, a Hollywood Movie called ‘The Way’ staring Martin Sheen portrayed a fictionalized account of the French Route from St Jean de Pied de Port. The media attention given to the Camino de Santiago has resulted in an increased number of pilgrims. In 2001, a German comedian, Hape Kerkeling did the Camino Frances and published a book in 2006 on his experience. The Pilgrims’ Office noted an increase in the number of German pilgrims the following year. They similarly noted an increase in American pilgrims after the release of The Way.

While the French route is currently the most popular one, there are various routes to Santiago: the Northern Route (Norte); the English Route (Ingles); the Primitive Route (Primitivo), the Portuguese Route (Portugues); the route from Seville (La Plata); and the route from Valencia (La Levante). Over the years, I have walked to Santiago along some of these routes: the Portugues in 2009 (200km in 10 days); the Ingles in 2010 (100km in 5 days); the Primitivo in 2011 (280km in 14 days). In 2012, at the invitation of the CSJ (Confraternity of St. James) I was invited to work in the Oficiana de Peregrino (Pilgrim’s Office); in 2013, I worked as a volunteer in a pilgrim’s hostal (The Albergue del fin de Camino); and in 2014, I did the last 100km of the Norte. All of these experiences allowed me to explore different aspects of pilgrimage. It was through my connection with the Pilgrims’ Office (Oficiana de Peregrino) that I met Prof. George Greenia, a distinguished academic in the field of pilgrimage and the consultant for the movie ‘The Way’, and was invited to give a paper at ‘Sacred Journeys: A Confluence of Pilgrimage Traditions’ an international conference run by the Institute of Pilgrimage Studies at the College of William and Mary.

A key theme that was explored in my paper was ‘shifting identity’. That is, how is a ‘peregrino’ identity formed, maintained and reshaped during and after the pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela. Regardless of the motivations people might have when starting out on the pilgrimage (i.e. an expression of Catholicism or Spirituality; personal achievement or completing a long distance trek with good facilities), these can change along the route and in different contexts. I have seen long distance trekkers start off by saying that they were not ‘peregrinos’ who finished the pilgrimage carrying the symbols of pilgrimage and participating in the rituals of arrival in Santiago. These rituals include going to the Pilgrims’ Office, attending the Pilgrims’ mass in the Cathedral, hugging the statue of St James and visiting the crypt where his bones are said to rest.

There is significant literature on whether or not ‘pilgrims’ can be considered as ‘tourists’ (Badone and Roseman 2004). This, I think, rather misses the mark as pilgrimage is a particular type of tourism, but ‘pilgrims’ also, in different contexts (going to a historic museum or finding a nice restaurant) can be more ‘tourist’ than ‘pilgrim’. Here, context is very important from the point of view of the pilgrim. What also needs to be considered is the impact that an increasing number of pilgrims have had on touristic infrastructure and how various towns and cities along the various routes have dealt with this (Gonzalez and Medina 2010). This can be linked to the issue of changing patterns of consumption along the ‘Camino’ and the notion of ‘authenticity’.

Is a pilgrim who stays in luxury hotels and pays to have their backpack taken to the next one as ‘authentic’ as one who stays in pilgrims hostels and carries their own backpack? Pilgrims have their own notions of authenticity and will judge and comment on others. I have seen many long distance pilgrims look down on those who only meet the minimum requirements. The Oficiana de Peregrino, however, has their own ‘official' view of authenticity as they have set conditions on what needs to have been accomplished for them to issue a certificate of completion (a Compostela). You need to have walked or ridden on horse back for at least the last 100km or cycled the last 200km of a recognized route to Santiago. This does not need to be done in a continuous push, but there can be no gaps where another form or transport was used. So some people can take years to finish a route, but they have to start from where they left off. he issue of ‘authenticity’ can also be seen in the routes themselves. On the Camino del Norte, for example, a deviation from the established route was proposed which was justified by the fact that historical research had determined that it was the ancient route and therefore more ‘authentic’. In 2014 I saw a number of signs saying ‘no al cambio (no to the change) along the section that had been declared ‘non-authentic’. Local communities and service providers were up in arms about this. When I asked why the change was implemented, they all thought it was for ‘interes’ (i.e. the communities on the ‘authentic’ route had political influence).

The new Compostela. Photo by author.

Going back to the Turner’s work, I do think that separation and communitas play a role in the formation of a ‘peregrino’ identity as does symbolism (or the consumption of symbols). If you wish to access pilgrim accommodation (around 10 euros a night) and get discounts on meals, you need to register as a pilgrim at your starting point and get a Credencial (pilgrims passport). Along the route, you collect stamps from churches, hostels, bars, restaurants, post offices, etc. which prove that you have walked, cycled or rode a horse along the route to satisfy the conditions set by the Pilgrims’ Office. Your Credencial is examined at the Pilgrims’ Office before you can be awarded a Compostela. Many ‘peregrinos’ also purchase a scallop shell or a gourd, which are traditional symbols of the pilgrimage to Santiago. Along the route you can purchase items of jewellery or clothing with symbols from the Camino, including way markings, route maps and significant landmarks. Even travelling with a rucksack or bike can be recognized as symbols of being a ‘peregrino’. These are recognized by locals and fellow peregrinos. I have seen and experienced locals offering refreshments and directions to peregrinos. Long distance peregrinos can be recognized by their distinctive tan lines: you often see people with brown legs, white feet and sandals wandering around towns along the routes once they are checked into their accommodation. Peregrino friendly cafes (i.e. those who open up very early when most set off) can be recognized by the pile of backpacks and walking sticks outside.

My backpack with a gourd, shell and Camino badges. Photo by author.

The highest degree of ‘separation’ can be seen in the long distance peregrinos. These are people who have taken a month or more off work. They carry with them symbols of their peregrino identity, use peregrino facilities, follow the same route as the other peregrinos (following the way markers) and often socialize with fellow peregrinos at night. Many of them will have come to know other peregrinos along the route. I have seen some very good examples of communitas form amongst groups of peregrinos, which as Turner (1969) indicated, is based on shared experiences while being separated from daily life. Common topics of conversation amongst peregrinos will be: where are you from, when and when will you start, how far are you walking tomorrow, what does your guidebook say about where to eat and sleep tomorrow? Pilgrims refer to themselves and each other as ‘peregrinos’ and a common greeting that you hear from locals and other peregrinos (many of whom don’t speak Spanish) is ‘buen camino’. This literally translates to ‘good way’.

Way markings on the Camino. Photos by author.

A good example of being separated from your daily life can be seen in Hans, a German peregrino I met on the Camino Frances. He said that he liked being on the Camino because no one ever asked him what he did for a living. His job had nothing to do with how he was ‘identified' on the Camino. He was German, he started in St Jean de Pied de Port and he was walking 25km the next day. I asked him what he did back in Germany. He replied: ‘I own an abbatoire back in Germany and trust me Nicole, that’s a real conversation killer’. Interestingly, he was one of the Germans who were inspired to do the Camino by Hape Kerkeling.

Separation can also be seen in the act of sending things back home. While all of the guidebooks and peregrino websites recommend a light backpack, most first time peregrinos start off with too much weight. What starts off as ‘necessary’ when packing at home, becomes regarded as ‘extra weight’ after several days of walking. What did I send back home during my first Camino? Camping cooking equipment was sent back as there are bars and restaurants where cheap food can be purchased. I’ve seen hair dryers, curling iron and make up sent back. I’ve seen people purchase light weight trekking trousers and post back jeans as they are heavy and take forever to dry. So, what you see is a gradual stripping away of what is not necessary and this process plays a part in the creation of a peregrine identity. However, I would also agree with Sallnow (1987) and Eade and Sallnow (1991) that total separation doesn’t happen for everyone. I’ve seen a particular increase in this since 2008 with the increased availability of cyber cafes, smart phones and wifi. Since 2009, I have participated in a peregrino forum (as peregrina nicole). One person asked, in 2009, about places where he could get wifi for his laptop. This provoked a flood of responses from people who said that he should leave his laptop at home and enjoy ‘getting away from it all’. By 2013, when I volunteered in a pilgrims hostel, the first thing that pilgrims asked about after being allocated a bed was the wifi Most people had smart phones and were checking their emails and updating their facebook pages.

Upon finishing the Camino, I’ve also seen a reluctance to return to ‘normal’ society. After a few days of rest in Santiago, many pilgrims choose to continue on to Finisterre and/or Muxia on the coast, which involves 3 to 4 more days of walking. Interestingly, the Pilgrims’ Office does not recognize this continuation as part of the pilgrimage. For them, pilgrims come to the Cathedral to visit St. James. As such, any pilgrim wanting information on continuing to the coast is directed to the tourism office. These two places, however, were part of the medieval pilgrimage. Muxia was the site where St. James was said to have first arrived in Spain in a stone boat. Finisterre, the ‘End of the Earth’ was thought to be the most westerly point on the European mainland. This is where a scallop shell would be collected as proof (along with the Compostela) that the pilgrimage had been completed. Today it is seen as the end of the Camino and many pergrinos choose to burn something, such as walking shoes, to symbolize the end of being a peregrine. However, being a peregrine, for many, doesn’t really end. The publication of personal accounts, keeping up with new Facebook friends, getting a tatoo and participating on the Camino forum are ways of maintaining a peregrino identity. Doing another Camino also reflects this. While most of the people I met on the Camino Frances were first time pilgrims, those I met on other routes were serial peregrinos.

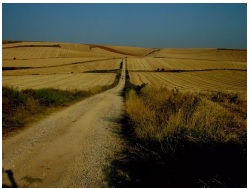

Something which has been under-researched in pilgrimage studies is the role of embodiment in the creation of a peregrino identity. One of the criticisms of the film 'The Way' from people who have done the Camino de Santiago was the absence of any reference to blisters, sore feet, swollen joints, back pain, chafing and the weight of the pack. The physical and mental embodiment experienced while walking is referred to by Slavin (2003) who clearly went through the experience of pilgrimage (participant observation) rather than simply interviewing pilgrims about their experiences. He notes how the repetitive act of walking long distances can lead to a meditative state or mental embodiment. This is connected with physical embodiment as people sometimes endure pain as they continue to walk. A good example of this can be seen in Martin from Australia, who I also met on the Camino Frances. Martin had back problems and wore a back brace. While walking alone on the meseta (an area of flat land between Burgos and Leon) he was alone and simply stared at his feet while walking. He noticed that his toes pointed inwards and he made a conscious effort to walk with his feet straight. By the end of the Camino, he had corrected his walking and no longer had back problems. While working in the Pilgrims’ Office, I saw many peregrinos limp in, clearly in pain, but delighted that the had completed the Camino.

The Camino on the meseta

Photo by author.

Along with the idea of embodiment comes the notion of inscription. As mentioned above, some peregrinos literally inscribe the Camino onto themselves in a permanent manner by getting a tattoo. The picture below is but one example. A google image search on ‘Camino de Santiago tatoos’ will reveal many more. Inscription doesn’t only happen on peregrinos, peregrinos also inscribe the landscape. There are areas where peregrinos leave items, such as the Cruz de Ferro (Iron Cross) and Finnesterre, and make crosses out of twigs and insert them into fences. I particularly like the happy sunflower below which someone inscribed on the meseta on the Camino Frances. It was a long hot day when I passed it and it made me smile.

Inscribing the Camino. Photo by author.

Inscribing the Camino on the body. Photo by author.

I’ll finish off this post by referring back to the conference I attended. You can use the link at the beginning of this post to see the wide variety of papers that were given. This provides an excellent snap shot of the breadth of pilgrimage studies. There were papers on pilgrimage during medieval times. This involved documentary research, including diaries from pilgrims. There were cultural studies papers that looked at factual or fictional accounts of pilgrimage in books and films. There was a paper on the use of modern technology during pilgrimage. Pilgrimage is an important topic not just for anthropologists and sociologists, but for a wide variety of disciplines. An interesting development is the use of pilgrimage in teaching. The College of William and Mary runs a summer school where undergraduates are engaged in various fieldwork projects and can get credit for this. Their work was presented as posters at the conference. The fee for this is expensive ($5925 in 2014) and working through health and safety issues was a challenge for the organisers, but both students and staff found this a rewarding experience (http://www.wm.edu/summerstudyabroad). The Spanish Institute for Global Education in Seville, who had representatives at the conference, is starting a programme in the summer of 2015 taking students along the route from Seville where they will have discussions on history, culture, geography, food, pilgrimage and language along the route. This was described to me as ‘an open classroom’. The programme is entirely in Spanish, but if you are interested, you can contact Dr Migule Nieto Nuno (mnieto@us.es).

I would also recommend the following websites:

- Camino de Santiago Forum (an excellent resource where I have asked and answered questions)

https://www.caminodesantiago.me/community/ - Mundi Camino (has maps and downloadable route descriptions)

http://www.mundicamino.com/en/index.cfm - Confraternity of St James UK (this organization offers advice and guidebooks and runs information events across the country, including Glasgow).

http://www.csj.org.uk - Pilgrims Office in Santiago de Compostela (This offers practical advice on the pilgrimage and the issuing of Compostelas)

https://www.caminodesantiago.me/the-pilgrims-office - Johnny Walkers Blog (this is an excellent blog set up by a Glaswegian volunteer who works in the Pilgrims’ Office)

http://johnniewalker-santiago.blogspot.co.uk/

References

Badone, E. and Roseman, S. (eds) (2004) Intersecting Journeys: An Anthropology of Pilgrimage and Tourism. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Coleman, S. (2002) ‘Do you believe in pilgrimage?: Communitas, contestation and beyond’ in Anthropological Theory 2(3): 355-368.

Coleman, S. and Elsner, J. (eds) (2003) Pilgrim Voices: Narrative and Authorship in Christian Pilgrimage. New York: Berghan Books.

Gonzalez, R. and J. Medina (2010) ‘Cultural Tourism and Urban Management in Northwestern Spain: The Pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela’. Tourism Geographies: An International Journal of Tourism Space, Place and Environment 5(4): 446-460.

Sallnow, M. (1987) Pilgrims of the Andes. London : Smithsonian Institution Press, Slavin, S. (2003) ‘Walking as Spiritual Practice: The Pilgrimage to Santiago de

Compostella’ Body and Society 9(1): 1-18.

Turner, V. (1969) The Ritual Process. Chicago: Aldine.

Turner, V. & E. Turner (1978) Image and Pilgrimage in Christian Culture. Colombia: Colombia University Press.

* * *

Dr Nicole Bourque is a Senior Lecturer in Social Anthropology in the Sociology Subject area of the School of Social and Political Sciences, University of Glasgow. Her main research interests are religion, ritual, religious change, syncretism and conversion. She has done fieldwork in outh America, Spain and the UK.

First published: 1 December 2014

<< Anthropology