A reflection on the relevance of systems approaches

Published: 29 October 2025

University of Glasgow post-doctoral researcher Elizabeth Inyang reflects on the relevance of applying systems approaches in her work with the GALLANT systems transformation team.

Working as an early career researcher on the GALLANT systems transformation team has prompted me to reflect more deeply on the value of systems approaches in tackling complex social and public health challenges—both within academic research and in broader practice.

As a discipline, systems thinking seems to have gained acceptance in some areas of research and/or practice, but it still doubtlessly seen as a novel approach in others.

However, systems thinking is actually quite intuitive. For example, people do not think nor behave as if getting to work on time is purely dependent on whether there is fuel in their car. They consider a whole network of related and dynamic things: the timing of rush hour, convenience of public transport, presence of road works, whether their car has a valid MOT...; and beyond transport itself, they will consider childcare or school schedules, current weather conditions, and going to bed/waking up on time.

Looking at things while broadly considering their context is part of daily life. It is more or less systematically done by individuals embarking on a new project; and it is a part of most traditional ways of thinking - a saying like ‘a stitch in time saves nine’ is deeply rooted in broad contextual understanding!

Research disciplines which engage with problems of human health and wellbeing have also developed tools to assist with looking at the wider context, for example the Dahlgren and Whitehead model (1) of health determinants. This model places the individual in a layered context of individual lifestyle factors; social and community networks; living and working conditions; and general socio-economic, cultural and environmental conditions. It therefore systematically considers the rich context that will affect an individual’s health.

So what does the formal discipline of systems thinking add to scientific research?

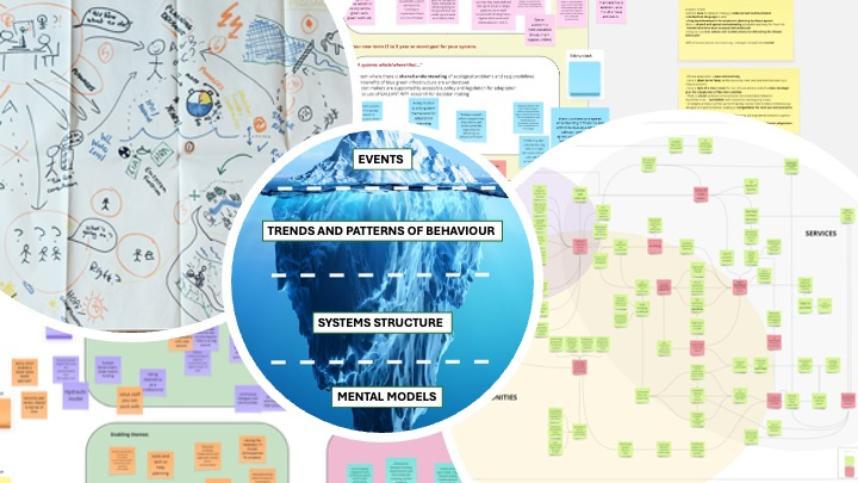

It does bring a theoretical framework, methodologies, and tools (2), which support inquiry and engagement with complexity wherever we find it. Its range of hard and soft (problem structuring) systems tools make it adaptable to both well-defined and messy questions/scenarios. Hard systems approaches are utilised where the question being addressed is objectively defined, and soft approaches in exploring and structuring poorly defined/messy issues, where subjective human perspectives on the issue play a strong role (3). The methods can be used in combination, for example soft methods can be used to surface the most relevant elements in a situation of interest to be included in a simulation model (4).

The principles of systems thinking can also enrich tools developed outside this discipline to better capture or analyse complex issues. To continue with the earlier example, the Dahlgren and Whitehead model can be enriched to explicitly look for feedbacks and interdependencies and so to capture a more dynamic picture. The creators of that model did update it with multidirectional arrows1 between the four layers. This was to better illustrate vertical interconnectedness between the layers of health determinants, for which they saw a need.

However, systems thinking has at its disposal a variety of tools and methodologies designed precisely to explore the interconnectedness, from hard modelling approaches like the stocks and flows of system dynamics models (5); to the human systems of purposeful activity of soft systems methodology6; to the questions defined by critical systems heuristics (7) exploring how we do, or ought to, define our system boundaries.

In effect, systems thinking pauses at the understanding-building stage of inquiry, aiming to avoid or minimise the unintended consequences risked by a less contextually informed approach.

For practitioners outside and inside the research space, systems approaches would therefore be very relevant. In policy development, the question of how to steer messy, large-scale situations in a context of possibly limited control can only benefit from an approach which complements the more traditional sources of evidence, and seeks coherence in the big picture.

Systems approaches recognize that complex systems – such as those in social and public health – tend to adapt in response to change, often in ways that allow them to maintain their core functions. Because these systems are shaped by the varied perspectives and purposes of the people within them, they are not easily controlled. As a result, interventions hoping to create lasting change must be grounded in the specific context; be participatory, involving the people affected; and iterative, evolving over time through ongoing learning and adjustment.

In research and policy, reductionist approaches are deeply established, largely because the scientific method which derives its strength from breaking complex phenomena into simpler, measurable components is powerful. It allows precise testing in a controlled environment to establish definitive causal links, but it to do this it needs to exclude the broader influencing factors which exist in real life contexts, and which systems approaches seek to usefully capture.

The reductionist approach of necessity also assumes ‘the system’ to be static to some degree, which the problems of human health and wellbeing cannot be as they are dynamic - always responding, adapting, and evolving. Systems models incorporate time delays and utilise feedback loops, which means that output is dependent on previous output; and so they can display the behaviour of a system changing over time.

Tackling the complex social and public health issues of our day needs an approach which complements the linear, one which explores the broader context and surfaces the relationships between the elements in complex problems, allowing us to better understand the behaviour of the whole. Uncovering these relationships allows a more deeply informed consideration of options and potential harmonisation of understanding, purposes, as well as costs of intervening to improve.

We do need to pause and build understanding—not just by mapping well-defined systems to identify leverage points for change, but also by making sense of the complex, messy, poorly defined situations which are shaped by diverse or conflicting human perspectives and purposeful actions. The latter is where soft systems approaches offer their distinctive value.

‘Joined up working’ is a currently popular phrase, but it seems not so easy to apply in practice. Topical and operational ‘compartments’ do in some way remain necessary in order to keep producing the knowledge or action they do (without an accounts department we would not get paid, for example), but they cannot remain siloed if cohesion is to be achieved. They need to be bridged while at the same time preserving the integrity which allows them to continue making their contribution.

To conclude, I would like to reflect on bringing a soft systems perspective to the work of the GALLANT systems transformation team. We applied a toolkit of selected soft systems tools in workshops with researchers and local council collaborators working on flooding. Gathering their perspectives in a structured way has highlighted the complexity of the issue, allowed us to surface the perceived barriers and enablers to building climate resilience in this situation, and to identify similarities and differences for researchers and collaborators. It has supported building a shared contextual understanding of the situation, and an understanding of the needed direction of travel for improvement.

Transdisciplinary collaboration presents its own practical challenges, and participants have found the process valuable for gaining insight into each other’s perspectives, as well as understanding the roles, constraints, and priorities of other stakeholders.

The systems thinking framework, tools, and methods allow tackling messy, complex human and social problems to be approached in a structured, systematic and tested way. The problems will remain messy, but the responses can begin to be less fractured and more cohesive.

Dr Elizabeth Inyang

- Dahlgren, G. & Whitehead, M. The Dahlgren-Whitehead model of health determinants: 30 years on and still chasing rainbows.Public Health199, 20–24 (2021).

- Peters, D. H. The application of systems thinking in health: why use systems thinking?Health Res. Policy Syst.12, 51 (2014).

- Checkland, P.Systems Thinking, Systems Practice. (John Wiley & Sons, 1981).

- Holm, L. B., Dahl, F. A. & Barra, M. Towards a multimethodology in health care – synergies between Soft Systems Methodology and Discrete Event Simulation.Health Syst.2, 11–23 (2013).

- Sterman, J. D. System DynamicsModeling: Tools for Learning in a Complex World.Calif. Manage. Rev. 43, 8–25 (2001).

- Checkland, P. & Scholes, J. Soft Systems Methodology in Action. in (1990).

- Ulrich, W. A Brief Introduction to Critical Systems Heuristics (CSH).

First published: 29 October 2025