What You See Is Not Necessarily What You Get: A Caveat for Scandinavian Place-name Evidence

Yumi Yokota (English Language: University of Glasgow)

| Introduction | |

| 1 | History books describe the Scandinavian invasion, the life and conditions of the Scandinavian settlers, their political relations to the English, and provide us with a general idea of Scandinavians on English soil. They have, however, left many questions unresolved, particularly with regards to the nature of the settlements and precise areas of major settlement sites. This ambiguity is magnified by the fact that conquest by arms does not necessarily imply subsequent settlement. |

| 2 | Archaeological evidence sheds some light on this matter. Objects excavated bearing Scandinavian runic inscriptions have all, with the exception of one in London, been found in areas generally agreed to have been heavily settled.[1] Another source of clarification comes from the Anglo Saxon Chronicle (ASC) which notes the movement of Scandinavian invaders toward the north and east and the English struggle against them. It refers to actual settlement by the Scandinavian army, however, only three times under the years 876 (in Northumbria), 877 (in Mercia), and 880 (in East Anglia):[2]

These archaeological and textual references, though useful, provide no more than a vague indication of the general areas in which the Scandinavians settled.[4] |

| 3 | Hitherto most scholarly discussion of settlement demographics has been largely based on the study of the Scandinavian influence on place names.

|

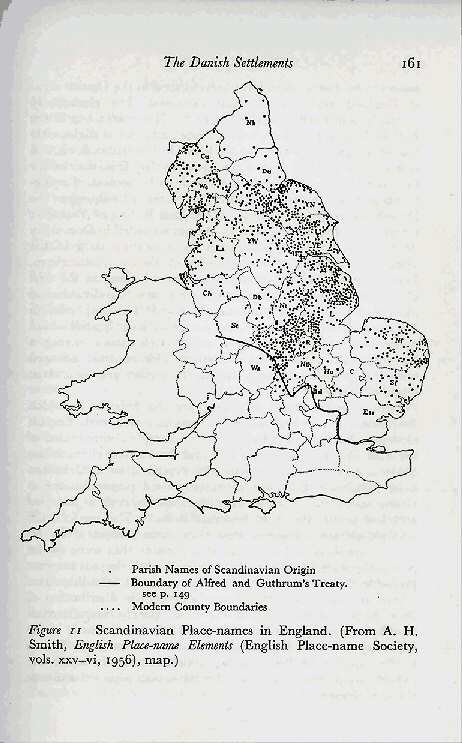

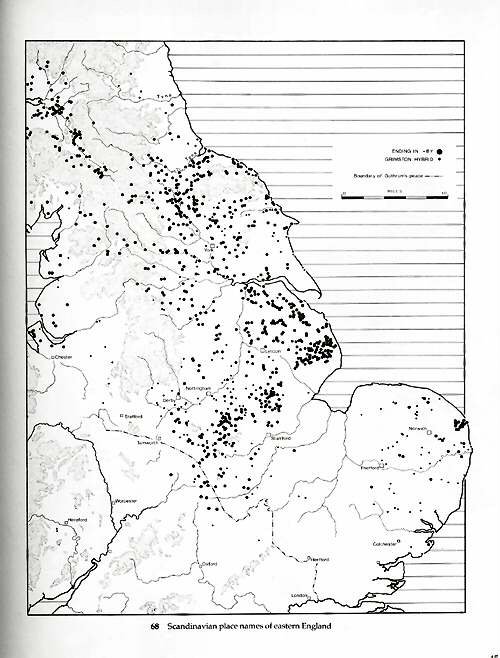

| 4 | 1400 places in England are considered to have Scandinavian names and most of them are in the former Danelaw. Within this area, the heaviest concentration of Danish place-names can be found in two main areas, the territory of the Five Boroughs (Lincoln, Nottingham, Leicester, Derby and Stamford), where the Danish army base was located, and Yorkshire. The second greatest intensity of Danish place-names is in northern East Anglia. In the southern Danelaw and the northwest of Yorkshire, places with Scandinavian names are rather scattered. Norwegian elements appear in the place-names of the northwest, the result of Norwegian immigration from Ireland, the Isle of Man and the Hebrides. On the Wirral peninsula in Cheshire there was a compact Norwegian colony established by the immigration of Ingemund in 901 or 902. The Norwegians penetrated into York, where they created a Norwegian kingdom of York encompassing Cumberland, Westmorland, and Lancashire. Place-name evidence left by men of Norwegian origin is abundant in Yorkshire North Riding, much less so in Yorkshire East Riding and Yorkshire West Riding, and also as far as the western parts of Durham and Northumberland. |

| 5 | Scandinavian place-names can be divided into three groups: (1) names containing Scandinavian inflectional patterns, (2) names derived from Scandinavian sound substitution and (3) names combining Scandinavian personal names with Scandinavian place-name elements. While this division is useful, certain place-names do not confine themselves to a single neat classification as in the case of place-names which incorporate Scandinavian personal names and English place-name elements. |

| 6 | The first group comprises place-names coined by people actually speaking Scandinavian languages. These place-names combine Scandinavian personal names and Scandinavian place-name elements using Scandinavian genitive inflectional endings. Two of the most common such endings are -ar as in Amounderness, Litherland, Scorbrough (Old Norse (ON) Agmundarnes, Hlíðarland, Skógarbúð) and -s as in Braceby, Rauceby, Winzebi (Old Danish (ODan) Breiþsby, Rauþsby, Wintsby).[6] |

| 7 | In the second group, English place-names are modified by the adoption of Scandinavian sounds or synonyns. Many English names contained sounds or sound-groups unfamiliar to the Scandinavians so they substituted those familiar to themselves. The English sounds /ò/ and /tò/, and /d/ between vowels or in a final position were unknown to Scandinavians of the time. So, names such as Shelton, Shipton, Cheswick, Childwick, Loud, and Middop were modified to Skelton, Skipton, Keswickv, Kildwick, Louth, and Mythop. Similarly, the substitution of a Scandinavian synonym for an English place-name element was extremely common: Old English (OE) brad "broad" was replaced by ON breiðr as in Braithwell (Bradeuuelle in Domesday Book), OE circe "church" by ON kirkja as in Kirton, Peakirk (Pegecyrcan in Domesday Book), OE cyning "king" by ON konungr, as in Coniscliffe (Ciningesclif in ASC), Coniston, OE stan "stone" by ON steinn as in Stainly, Stainton and so on. |

| 8 | In the third and final group, Scandinavian personal names are found attached to Scandinavian place-name elements such as -by and -thorp. This group also includes hybrid-type place-names in which Scandinavian personal names are combined with English place-name elements such as Grimston, Kettlestonv, Thurstonfield from Scandinavian Grímr, Ketil, Þorstein used in combination with English tun and feld. |

| 9 | Numerous Scandinavian place-name elements are used in England, such as by, thorp, toft, lathe, thwaite, garth, fell, how, meol, holm, wray, wath, scough, with, lund, beck, tarn, crook, gate, both, etc. Some of these elements may be used as test-words for Danish or Norwegian origin: Danish test-words are thorp, both, hulm and Norwegian ones are breck, buth, gill, slack and scale (Ekwall 1936: 139). Place-names containing the elements -by and -thorp, and the Grimston type hybrids are considered of great importance as the great frequency of -by and -thorp in the Danelaw is usually regarded as the most distinctive sign of heavy Scandinavian influence. Areas where these elements are found are considered to represent major Scandinavian settlement sites. |

| 10 | The place-name element by (ON býr bœr, ODan and Old Swedish by) means "village" or "town" in Danish and "homestead" in Norwegian. Approximately two out of every three place-names ending in -by are combined with Scandinavian personal names,[7] and others are combined with terms for directions such as south and east,[8] the nationality of settlers,[9] and topographical features.[10] According to the geographical evidence in the areas of the Five Boroughs and in Yorkshire, place-names incorporating -by represent the best available vacant land (Loyn 1994: 85). In many cases, personal names combined with -by can be the names of the subordinate leaders of the so-called "great army" which formally occupied and settled in eastern England during the years 876-880 (Wainright 1962: 82). |

| 11 | Thorp (ON þorp) means in Danish "a hamlet or a daughter settlement dependent on an older village"(Ekwall 1936: 139). There was also a word þorp (þrop) in OE, and its combination with English personal names may be considered as English. Thorp is a common place-name element in Denmark and Sweden, comparatively rare in Norway, and absent in Iceland. It is very common in the Danelaw, but very rare in the north western counties where Norwegians settled.[11] Thorp was also frequently combined with Scandinavian personal names and other Scandinavian words[12] to form place-names. These names were often given to areas less suitable for agriculture. Their numerous occurrence and their distriution pattern in the northeast can be interpreted to mean that places with -thorp names are those areas which were exploited not by original army settlers but by later Scandinavian immigrants. This argument finds some support in Domesday Book, which suggests that the areas of settlement had been greatly enlarged in the preceding two centuries (Loyn 1994: 86). |

| 12 | There exists a substantial quantity of names in the Danelaw which contain Scandinavian personal names compounded with the English element -tun. These are known as 'Grimston hybrids'. They are so called because the most commonly used personal name is Grimr and the most frequent place-name element is tun[13] followed by feld, ford and leah. The element tun, though considered to be English, would probably have been used unaltered by the Norwegian settlers in England on the basis that names containing -tun are common in Iceland (Ekwall 1924: 58). In general these hybrid names occur in districts where there are a preponderance of English place-names and very few -by names. These names are generally attached to agricultural land of good quality, which was less likely to have been left vacant by the Englishmen before the Scandinavina settlers came. They may well in fact have been native English villages exploited by Scandinavians in the very early stages of settlement when army leaders took over the lordship and initiated a degree of settlement on already favoured agricultural sites (Loyn 1994: 86). |

| 13 | In many cases the Scandinavian personal names combined with -tun, like many of the personal names combined with -by, may be the names of the subordinate leaders of the great army who settled with their followers in the year 876-880 (Wainright 1962: 83). They are more common in Nottinghamshire and Leicestershire but not so in Lincolnshire and Yorkshire, where -by and -thorp types of place-names are predominant. In those areas where the hybrid names appear, the English population is thought to have been predominant. |

| 14 | Some scholars believe that great frequency of place-names with -by and -thorp in the Danelaw presupposes an abundant existence of people who spoke Scandinavian languages and that they consequently show the main areas of the Scandinavian settlement. This opinion should be handled with caution, however, because not all of those place-names can be regarded as a direct result of Scandinavian migration. The place-name element -by remained productive even after the Norman Conquest, and it is quite possibly just a replacement of the native place-name element -byrig. Aside from the ambiguity of -by there are further complications brought about by the alteration of personal-names and the coinage of place-names themselves. There is even the possibility that some Scandinavian immigrants chose not to change English place-names when they assimilated themselves into a village or area occupied by native Englishmen. |

| 15 | One of the primary elements of confusion regarding place names is that by continued to be a productive nominal element until at least the twelfth century in certain districts. In Cumberland there are several examples of late formations of -by place-names. These include places incorporating Norman personal names (Aglionby "Agyllum's by",[14] Botcherby "Bochard's by", Johnby "John's by", Ponsonby "Puncun's by") and names such as Flimby, which implies a site settled by the Flemish in the time of Henry I (Ekwall 1936: 157, Geipel 1971: 126-127). These place names do not prove the existence of Scandinavians in the area. The coinage of these names is more likely to be connected to the local language or local name-giving practice, which was influenced by Scandinavians. Thus, the assumption that the distribution of -by place-names defines the main areas of Scandinavian settlement should be re-examined with specific attention given to chronology in order to use those place-names accurately in studying the extent and progress of the Scandinavian settlement. |

| 16 | There are some instances where the native place name element -byrig was simply replaced by the Scandinavian place name element -by. Greasby in Cheshire appeared in Domesday Book as Gravesberie, Naseby as Navesberie, and Rugby as Rocheberie. (Geipel 1971: 126-127) In these cases the -by element is no longer regarded as Scandinavian and it is impossible to ascribe those -by names to Scandinavian settlement sites. |

| 17 | The Scandinavians brought with them a distinctive stock of personal names.[15] Their abundant distribution in the north of the Danelaw marks a distinct contrast with their paucity in the south of the Danelaw.[16] The strong northern occurrence agrees with the linguistic evidence, which shows the northern Danelaw area as more strongly Scandinavianized than the south of it (Stenton 1971: 520, Loyn 1994: 88, Samuels 1985). This abundance of Scandinavian personal names, however, should not lead us to conclude that men with Scandinavian names were the descendents of Scandinavian settlers, nor to assume that place-names which contain Scandinavian personal names necessarily refer to Scandinavians or Scandinavian descendants. |

| 18 | There are a considerable number of examples of the blending of English and Scandinavian names in the same family (Davis 1955: 29, Arngart 1928: 80). There was in the tenth century a priest called Athelstan whose brothers were called Ælfstan (English) and Bondo (Scandinavian),[17] and a man bearing the English name Eadric, whose brother is called Grim, an undoubtedly Scandinavian name. A widow, whose husband has the English name Wineman, has brothers called by the names of Osulf, Fastolf and Beorneh, of which Beorneh is an undoubted and Osulf a possibly English name, while Fastolf is certainly Scandinavian. A man called Fryðegist, a Danish name, has sons named Osferð and Adeluuold, of which at least Adeluuold is unquestionably English.[18] This shows that name-giving habits in England had been changed, probably due to intermarriage of Scandinavians and English, or, if not, affected profoundly by the example of Scandinavians who were the socially dominant class in some areas. Likewise, in the thirteenth century a large number of the names in use among the small landowners and peasantry in all parts of England were those introduced by the Normans and their continental friends (Sawyer 1971: 156). The repertory of personal names available to the English was increased by both the Scandinavians and the Normans. |

| 19 | The fact that men with Scandinavian names were not necessarily Scandinavian by race seriously affects the interpretation of place-names containing Scandinavian names, because they could be used by Englishmen as easily as Scandinavians. |

| 20 | In using this place-name evidence for Scandinavian settlement, it should be remembered that place names were not generally given by the inhabitants. They arose spontaneously, unconsciously (Ekwall 1924: 72) or they were given by the neighbours out of some local characteristics, the owner's name, or some other circumstance and came to be used in referring to the place. Place-names are thus likely to reflect the predominant nature or nationality of a district, which was felt by people in the adjacent areas. A strong Scandinavian element must have existed where the Scandinavian place-names occur. However, this does not necessarily imply Scandinavian numerical superiority for inferiority in numbers may have been counterbalanced by political or social superiority (Ekwall 1936: 139). |

| 21 | When names are given by next-door neighbours, we have to consider the languages of the name givers. It is possible that Scandinavian place-names were created not only by Scandinavians who had settled in the ninth century or the descendants of these settlers, but also by native Englishmen. In areas of intensive interaction between the two peoples, the speech of English could itself have been strongly influenced by Scandinavian. The mixed language situation was more likely to be reinforced by a new influx of Scandinavian speakers in the tenth and eleventh centuries from areas such as Man, where the language persisted much longer (Page 1971: 165-181, 1973: 190-199). Such a name as Ingleby 'village or farm of the English' suggests that the English nature of the area was itself distinctive (Sawyer 1971: 154-155). Scandinavians or their descendants could have given the area this name based on its "English-ness". Conversely, a place named Denby or Danby 'village or farm of the Danes' implies that Danes were a distinctive feature in that region. Despite this name, it could have been named by someone who was not Danish but was familiar with the Danish name-giving practice of appending using -by, an Englishman, for example, whose speech was strongly influenced by Scandinavians. These examples clearly demonstrate that -by could be used by both English and Scandinavians. This challenges an interpretation of place-names made by Ekwall, whose view is that "names in -by presuppose a population that spoke a Scandinavian language" (1936: 138-9) and "all or practically all English place-names in -by are Scandinavian in the strict sense"(1924: 57). |

| 22 | Scandinavians not only entered the available vacant areas left by English, but also mingled among them to live. When they settled in areas pre-occupied by English, they would frequently take over the old place-name unchanged when the name offered no phonetic difficulties to them (Ekwall 1936: 139). Thus, the absence of Scandinavian place-names in a district need not prove that no Scandinavian immigration took place. Misleading factors of massiveness Scandinavian immigration was frequently described as 'massive', 'numerous', and 'considerable in number'. These assumptions are often based on the the evidence of considerable linguistic influence. Before we talk about the 'overwhelming' ON influence, however, we should not underestimate the similarity between Anglian dialects of OE spoken in the north and east of the country and ON. Lund (1981: 160), in his discussion on English field-names, states that:

Ignoring these similarities can, in a way, often lead us to misjudge the number of original Scandinavian settlers[19] as well as the extent of Scandiavian settlement sites. |

| 23 | It is tempting, or perhaps just convenient, to judge that -by and -thorp are of Scandinavian origin when various maps show those are densely concentrated in a given Danelaw area but quite rare outside the region. It is possible, however, that many of the place-name elements as well as words, regarded as Scandinavian in origin, did actually come from the eastern or northern dialects which are not recorded in any literary documents. The dialects in the north and east are often said to be somewhat closer to ON than was the West Saxon dialect. It is possible, therefore, that words of similar meaning and sound might have appeared in the speech of Englishmen in the Danelaw area before the arrival of Scandinavians, and because of this similarity Englishmen in the north and east might easily have accepted those Scandinavian elements unconsciously. This situation could have been accelerated after centuries of close social interaction between the two peoples. The acceptance of grammatical words such as pronouns, least transplanted from one language to another, cannot merely be the result of casual influence but must have the cooperation of internal linguistsic change of OE. In addition, the acceptance and integration of lexical words such as legal terms and everyday speech are not necessarily attributable to the numerical volume of Scandinavian settlers alone but could have as easily arisen from various domestic sources. |

| Conclusion | |

| 24 | The first survey of English place-names, for the purpose of compiling Domesday Book, was made in 1086. It describes most of the place-names which then existed in England, but it is clearly irrelevant for the study of the original settlement in the second half of the ninth century as mentioned in the ASC. Nor does it demonstrate the density and extent of the Scandinavian population at that time. During the two hundred years between the first Scandinavian settlement and the first survey, there was a considerable influx of Scandinavian immigrants from the continent. Given that the Scandinavian and English languages shared certain characteristics from the beginning, it is not difficult to assume that the languages of the natives and settlers were at times easily intermingled, ultimately making interpretation of the origin of place-names extremely difficult. |

| 25 | The vagaries associated with measuring Scandinavian linguistic influence often affect the way the scale of Scandinavian immigration is described and consequently tends to lead us to a lopsided view about the Scandinavian settlement. Despite all these difficulties, what do the maps actually tell us in concrete terms? They show us something about the areas of contact between Danish and English speakers and indicate the spheres of life in which Danes were influential. Scandinavian place-names, while not definitive in determining settlement sites, are very important as indicators of the distribution and the relative intensity of the Scandinavian settlements. |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Endnotes

[1] There is one in Lincolnshire (Lincoln), three in Cumberland (Bridekirk, Carlisle, Dearham), one in Yorkshire North Riding (Skelton-in-Cleveland), one in Yorkshire West Riding (Settle), and two in north Lancashire (Conishead Priory, Pennington) as shown by Page, R.I.(1973) An Introduction to English Runes. pp.194-9.

[2] Ekwall (1936: 133 footnote 3) notes that in the anonymous Historia de Sancto Cuthberto (c. 1050) there is mention of a fourth systematic settlement by Scandinavians in Durham between the years 912-15.

[3] Quotation of the ASC is from Earl, J. & Plummer, C. (1980) and its translation is from Garmonsway, G.N. (1994).

[4] Cameron (1961: 75) has made an attempt to specify the settlement site made by these hosts in an earlier time.

[5] The following observation is based on Ekwall (1924) pp.71-86 and Ekwall (1934) pp. 140-159.

[6] Lund (1981: 168) shows a counter example: German genitive is used in place-names in the village of Fyn in Denmark despite the lack of heavy German colonization or a great number of German speakers. This resulted from the fact that some Holstein magnates held the castles of Funen for part of the fourteenth century.

[7] For details see Geipel (1971: 126).

[8] Oustinby from 'south' and Austebi from 'east'.

[9] Denby and Denaby (village of the Dane or Danes), Ingleby (village of the English), Scotby (village of the Scot), Frisby (village of the Frisian), Normanby (village of the Norwegian). Cameron (1961: 81) regards these place-names as valuable sources because they indicate that the settlers in various districts were not homogeneous groups.

[10] Aby (ON: ár 'river'), Lumby (ON: lunder 'grove'), Mickleby (ON: mikill 'large'), Raby (ON: rá 'boundary mark').

[11] The Concise Oxford Dictionary of English Place-Names (CODEP). 3rd ed. (1947)

[12] For details see Geipel (1971: 128).

[13] Gillian Fellows Jensen, Scandinavian Personal Names in Lincolnshire and Yorkshire (1968) Copenhagen, pp. Lxii-iii.

[14] Each of the original forms is from CODEP.

[15] Using the Scandinavian personal names of the pre-Conquest Danelaw (Stenton 1971: 519-520) was challenged by Davis (1955). For further detail, see his argument.

[16] Stenton (1971: 520), having observed Domesday Book, mentions that Scandinavian personal names can be counted by hundreds in Yorkshire and Lincolnshire, and by scores in Nottinghamshire Derbyshire, and Norfolk. They also occur in considerable numbers in Leicester, Northamptonshire and Suffolk.

[17] Davis (1955) has quoted from Liber Eliensis, ed. by D.J. Stewart (1848)

[18] Arngart (1928:80) has quoted from Cartularium Saxonicum (dates from about 972-992). ed. by W de G. Birch.

[19] For various opinions regarding the approximate number of Scandinavian settlers, see Jones (1968: 218), Sawyer (1971: 128), Lund (1977: 168, 1971: 147), Wainwright (1962: 82), Davis (1955: 32), Hansen (1984: 79) and Kastovsky (1992: 323).

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Bibliography

Arngart, O. S. 1928. 'Some aspects of the relation between the English and Danish elements in the Danelaw', Studia Neophilologica, 20: 73-87

Baugh, A. C. and Cable, T. 1978. A History of the English Language.3rd ed. (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul)

Björkman, E. 1969. Scandinavian Loan-Words in Middle English. Reprint (New York : Green-wood Press)

Bynon, T. 1996. Historical Linguistics reprint (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press)

Cameron, K. 1961. English Place-Names (London: B.T. Batsford)

Clark, C. 1992. Onomastics, in Richard M. Hogg (ed) The Cambridge History of the English Language Vol. II 1066-1476. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press)

Davis, R. H. C. 1955. 'East Anglia and the Danelaw', Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, 5: 23-39

Earl, J. & Plummer, C. 1980. Two of the Saxon Chronicles Paralle reprint (Oxford: Clarendon Press)

Ekwall, E. 1924. 'The Scandinavian Element', in A. Mawer & F. M. Stenton (ed), Introduction to the Survey of English Place-Names Part 1 Chapter IV English Place-Name Society (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press)

-------------1930. 'How long did the Scandinavian language survive in England?', in Bøgholm, N., Brusendorff, A., & Bodelsen, C. A. (ed), A Grammatical Miscellany Offered to Otto Jespersen on his Seventieth Birthday, pp. 17-30 (Copenhagen: Levin & Munksgaard)

-------------1936. 'The Scandinavian Settlement', in H. C. Darby (ed) An Historical Geography of England before A.D. 1800 (Chapter IV) (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press)

-------------1937. 'The Proportion of Scandinavian Settlers in the Danelaw', Saga- Book of the Viking Society, 12:19-34

Fellows Jensen, G. 1968. Scandinavian Personal Names in Lincolnshire and Yorkshire (Copenhagen)

-----------------------1973. 'Place-Name Research and Northern History: A Survey', Northern History, 12:1-23

-----------------------1975. 'The Vikings in England: a review', in Peter Clemoes (ed), Anglo Saxon England, 4:181-206

Fisiak, J. 1971. 'Sociolinguistics and Middle English: Some Society Motivated Changes in the History of English', Kwartalnik Neofilologiczny, 24: 247-259

Garmonsway, G.N. 1994. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle (London: Everyman)

Geipel, J. 1971. The Viking Legacy - The Scandinavian influence on the English and Gaelic languages (Newton Abbot: David & Charles)

Gorden, E. V.1988. An Introduction to Old Norse 2nd ed. revised by A. R. Taylor (Oxford: Clarendon Press)

Hansen, B. H. 1984. 'The Historical Implications of the Scandinavian Linguistic Element in English', North-Western European Language Evolution, 4: 53-59

Hill, D. 1981. An Atlas of Anglo-Saxon England (Oxford: Blackwell)

Jones. G. 1968. A History of the Vikings (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press)

Kastovsky, D. 1992. Semantics and Vocabulary in: Richard M. Hogg (ed) The Cambridge History of the English Language Vol. 1 The Beginnings to 1066. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press)

Keller, W. 1925. 'Skandinavischer Einfluss in der englischen Flexion', in: W.Keller (ed) Probleme deenglischem sprache und Kkultur pp. 80-7. (Heidelberg: Johannes Hoops)

Kirch, M. S. 1959. 'Scandinavian Influence on English Syntax', PMLA, 74: 503-510

Kolb, E. 1965. 'Skandinavisches in den nordenglischen Dialekten', Anglia, 83:127-153

Kristensen, A. 1975. 'Danelaw institutions and Danish Society in Viking Age: sochemanni Iberi homines and königsfre', Medival Scandinavia 8: 27-86

Kristensson, G. 1967. A Survey of Middle English Dialect 1290-1350: The Six Northern Counties and Lincolnshire. (Lund: Lund Studies in English 35)

Loyn, H. 1994. The Vikings in Britain (Oxford: Blackwell)

Lund, N. 1977. 'The settler: where do we get them from - and do we need them?', in Bekker-Nielsen, H. , Foote, P. & Olsen O. (ed) Poceedings of the Eighth Viking Congress pp 147-171 (Odense : Odense University Press, 1981)

Olszewska, E. S. 1935. 'Type of Norse Borrowing in Middle English', Saga-Book of the Viking Society for Northern Research, 2:153-60

Page, R. I. 1971. 'How long did the Scandinavian Language Survive in England? The Epigraphical Evidence', in: Clemoes and Hughes (ed) England before the Conquest pp 165-81 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press)

-------------1973. An Introduction to English Runes (Woodbridge: Boydell)

Poussa, P. 1982. 'The Evolution of Early Standard English: The Creolization Hypothesis', Studia Anglica Posnaniensia, 14: 69-85.

Samuels, M.L. 1963. 'Some Applications of Middle English Dialectology' English Studies, 44: 81-94

-------------------1985. 'The Great Scandinavian Belt', in Eaton R., Fischer, O. Koopman, W. & van der Leek, F. (ed), Papers from the 4th International Conference on English Historical Linguistics, pp. 269-81 (Amsterdam: Benjamins)

Sawyer, P.H. 1958. 'The Density of the Danish Settlement in England', University of Birmingham Historical Journal, 6: 1-17

-----------------1971. The Age of the Vikings 2nd edn. (London: Edward Arnold)

-----------------1997. The Oxford Illustrated History of the Vikings (Oxford: Oxford University Press)

Smith, A. H. 1956. English Place-Name Elements. English Place-name Society, xxv-vi. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press)

Stenton, F. M. 1971. Anglo-Saxton England 3rd ed. (Oxford: Clarendon Press)

Strang, B.M. H. 1970. A History of English (London: Methuen)

Thomason, S. G. & Kaufman, T. 1988. Language Contact, Creolization, and Genetic Linguistics (Berkeley; Oxford: University of California Press)

Wainright F. T. 1962. Archaeology and Place-Names and History: An Essay on Problem of Co-ordination (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul)

-------------------1975. Scandinavian England (Sussex: Phillimore & Co. Ltd)

Wall, A. 1898. 'A Contribution Towards the Study of the Scandinavian Element in the English Dialects', Anglia 20: 45-135

Weinreich, U. 1953. Languages in Contact - Findings and Problems (New York: Linguistic Circle of New York)

Whitelock, D. 1961. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, a revised translation (London: Eyre & Spottiswoode)

eSharp issue: spring 2004. © Yumi Yokota 2004. ISSN 1742-4542.