Authoring the Author: Innovation and Enigma in Bibliothèque Nationale MS fr.146 the Livre de Fauvel

Kate Maxwell (University of Glasgow)

| 1 | This paper will discuss the issue of authorial naming in Medieval French musica, with particular reference to the early fourteenth-century manuscript Bibliothèque Nationale MS fr.146, the Livre de Fauvel. I will be considering its place in the development of the author figure from the near-anonymity of Chrétien de Troyes in the twelfth century to the development of Machaut's author corpus in the late fourteenth. In a time when secular works were circulated with very little reference to any kind of author figure (in this I include writer, composer, or artist), the targeted recipient was often called upon to decipher the author from his work, often with the use of an enigma such as the anagram. In this way, each reception of each text by a new individual was a site of play, open to negotiation and interpretation, and each work displays its own discursive trail. Here I would like to offer my new interpretation of the authorial naming in the satirical Livre de Fauvel, which may implicate a senior member of the Capetian royal family, Charles de Valois, uncle to the reigning king Philip V. |

| 2 | However it is first necessary to discuss the concept of reading and readership in the Middle Ages, for it could be argued that enigmas such as anagrams would be inaccessible except to the literate few. I will be using the word "reader" a lot in this paper. By "reader", I simply mean anyone who receives the text with access to the written word. This includes private, silent readers, those listening to a performance of words (set to music or otherwise) who may have had the opportunity to see the text, and regardless of whether they owned a copy of the manuscript in question. It is a common misconception that illiteracy was entirely rampant in the Middle Ages: Joyce Coleman in her book Public Reading and Reading Public in Late Medieval England and France has done much to overturn this view.[1] Without entering too far into the debate here, it is nevertheless important to point out that it is likely that much of the middle and upper classes, and of course those in even minor holy orders, would have been able to read. Imagine a public or a private reading, which could take the form of lovers reading to each other from a romance, a cleric reading to a monarch and nobles, or readings in public places to groups large or small. Coleman has compared public readings to modern-day soap operas, "with every evening bringing the latest instalment",[2] with the ensuing discussions that take place whenever such entertainment is received in a group, but with the added advantage that the reading could be stopped at any time for comment and not just during the ad-breaks. Therefore when discussing enigmas, I am imagining that they would be accessible to a wider audience than might at first be assumed. |

| 3 | I am now going to move on to the question of authorship. Works which have come down to us with an author-figure begin with those such as Chrétien de Troyes and Marie de France. "Christian" or "a Christian from Troyes" and "Mary from France" does not give us much of a clue as to the identity of the author him - or herself. Yet Chrétien is not afraid to name himself, and is aware of his status as author. Here he is boasting that his story - playing with the pun of his name - will be remembered as long as Christendom lasts - that is, for him, until the end of time:

Moving into the thirteenth century, we see authors becoming not just self-aware but taking an active part in their works. In Le Bel inconnu ("The Fair Unknown") the author Renaud de Beaujeu is an active character in the work, declaring that he will re-write the ending if his lady accepts his suit. It is here too that we also see the rise of the trouvère chansonnier, wherein the songs are arranged author by author, in descending order of social status. Silvia Huot, in From Song to Book notes the difference between "Ci commence d'Erec et Enide" ("here begins [the story] about Erec and Enide") in twelfth-century romance anthologies and "les chansons au Chastelain de Couci" ("the songs belonging to [that is, attributed to, authored by] the châtelain de Couci") in chansonniers.[4] Therefore in the thirteenth century we have the concept of intellectual property, if you like, for it is in these chansonnier collections of lyric works that "the figures of protagonist, author, and performer are united in the lyric 'I' ".[5] It is not until the Roman de la rose however that a narrative is written entirely in the first person.[6] |

| 4 | One of the earliest vernacular word games is in Christine de Pizan's Cent balades from the fourteenth-century where she makes the joke that "en escrit y ai mis mon nom" ("I have written my name in writing"). Laurence de Looze has unscrambled this to conclude that "en escrit" in fact spells "Crestine". He continues: The writing of her name becomes a writing of writing: a direct allusion to the whole project of écriture and to the identity between the poem's corps and the poem's corpus. Christine is writing, and 'Christine' is the writing of Christine. [...] She is supremely aware that to write is to be written and rewritten, that the authorial name bridges the chasm between the written and unwritten, 'en escrit' in the threshold where text meets world.[7] |

| 5 | I think this can be taken further. By the use of this anagram Christine invites her audience, be they fourteenth-century bourgeoisie or twenty-first-century conference participants, to take a part in her work, to take the final step to its completion, to add to it a further dimension. By the use of an enigma Christine invites her readers into a closer, more intimate circle than merely reading or hearing her work. For the invitation to solve the anagram is also an invitation to take up the task of the author and bring the work to its completion, and the development of authorial awareness moves through author-as-character addressing his lady to reader-as-author, addressing anyone who consumes the work. |

| 6 | Staying in the fourteenth century, we have the beginnings of the author corpus with the works of Machaut. Manuscripts of "collected editions", if you like, had existed in some sense prior to Machaut, however Huot has observed the irony that the one surviving manuscript which contains all of Chrétien's works is also one where there is a great deal of scribal editing - the work of the author is not sacrosanct. Chrétien's works, which often appeared in pairs or groups in manuscripts, are never introduced as such, and are never accompanied by an author portrait.[8] Machaut's works have come down to us in these "collected editions", complete with images of the author at work. The character of the author appears clearly in his works, whether or not they are truthful, telling his stories in the first person. Yet in Machaut's works, while the character of the author is visible, his name is hidden in an anagram. The mental agility required of the reader ranges from none (for example in the Jugement Navarre where he names himself outright as the author) to the "unsolvable" (at least for us, although they may have seemed less troublesome to Machaut's contemporaries) including that of the Dit de la Harpe, which simply do not reveal the poet's name. Some even claim to reveal the poet's name, yet do not. Therefore we are forced to either go against the instructions and adjust the given text to make the anagram reveal the author's name, or to accept that a near-name is all that can be found. In this case it is up to the initiative of the reader not only to take on an authorial role, but also to "bridge the gap" between text and author.[9] |

| 7 | So what does all this have to do with Fauvel? The Livre de Fauvel is a book in which ideas of authorship and issues of naming and identity come under the spotlight and the satirist's pen. It was compiled in Paris in the early fourteenth century, well before Machaut began his work. It is a book about a horse, Fauvel, who is raised to the French throne by Lady Fortune (Dame Fortuna), and who is petted (froter is the Old French verb) by everyone: nobles, clergy, royalty, even the pope. The basic story survives in a number of manuscripts, but this one, B. N. fr. 146, stands out because it is the sole surviving version to boast a greatly extended text of Fauvel together with a large number of images and musical compositions, as well as some additional poems, songs, and a non-fiction metrical chronicle. Whereas the earlier versions claim using enigmas to be written by Gervès du Bus, a clerk in the royal chancery, this version purports to have been re-written by a new author, Mesire Chaillou de Pesstain, as we shall see. |

| 8 | There are already several layers of play in Fauvel. Fauvel's name itself is an acrostic, spelling out (the letters V and U, as well as I and J, are interchangeable in the medieval alphabet) Flattery, Avarice, Villainy, Vanity, Envy, and Laziness. The very word itself means "false veil". Fauvel is fawn (fauve), the colour of vanity, which with its reddish overtones would have reminded its first readers of the highly popular cunning fox Reynard, and of Judas Iscariot, both of whom were red-haired. The word "fauve" already had negative overtones in Old French before the compilation of this manuscript. "Fauve anesse" (lit. "fawn she-ass") is used in the Roman de Renard to mean "hypocrisy" or "lie". Following or contemporary with the Livre de Fauvel Frédéric Godefroy's research from the turn of the twentieth century tells us that a "fauvelin" ("little fauvel") is a "hypocrite" or "trickster", the verb "fauveler" is to act hypocritically, and the word "fauvel" itself is defined as being "often used to signify hypocrisy, or falsehood".[10] |

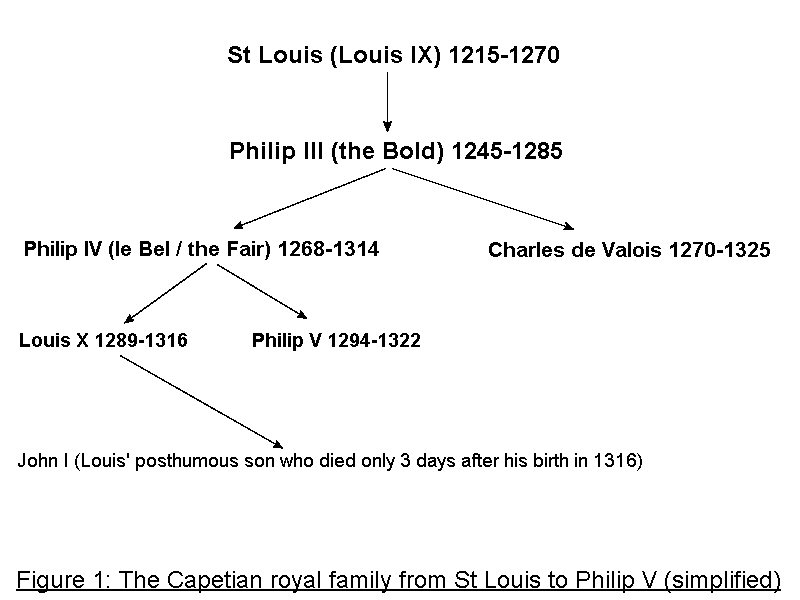

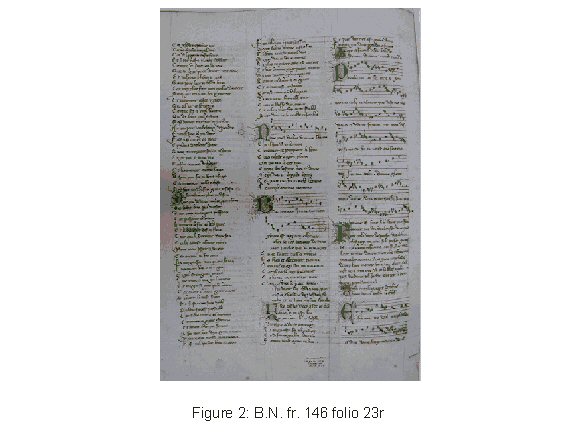

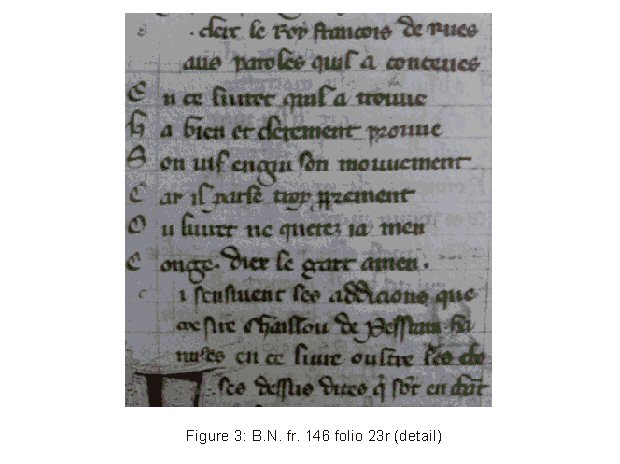

| 9 | The Livre de Fauvel is an allegory, directed against Enguerran de Marigny, a counsellor of Philip IV (the fair) of France. Marigny had a meteoric rise to fame, and was thought by many to have an undue influence over royal affairs, and came to a sticky end upon the king's death. Figure 1 is a very simplified diagram of the Capetian royal family, showing the descent from St Louis to Philip V. I will be referring in particular to Philip V, his brother Louis X, his father Philip IV, and his uncle Charles de Valois. In the story Marigny is already dead, so the referral to "Philip who is now king" must mean Philip V, and the work was possibly intended with him as audience. As for Charles de Valois, he has already been tentatively associated with the manuscript's production, for as well as the Fauvel story it contains the chronique métrique, a metrical chronicle which casts him in a most favourable light. It is generally agreed (by Emma Dillon and Andrew Wathey among others) that it was he, as a powerful figure who disliked Marigny, who allowed the book's compilation in order to educate his nephew Philip V against the dangers of allowing his underlings too much power as his father had done.[11] I would like to add that it is possible that he is implicated further in the authorial naming, which occurs on folio 23r (figures 2 and 3). It takes place on a very unassuming page, with no great author image, but it is at the halfway point in the story, folio 23 out of 46. |

| 10 | If there ever was anyone called "Chaillou de Pesstain", then his identity has eluded us all. Fauvel was almost certainly produced in the royal chancery in Paris, and it has been proposed by Elisabeth Lalou that "Mesire Chaillou de Pesstain" is a certain figure there who signed himself "Chalop", and who may have been from Persquen in Brittany. This is entirely feasible although somewhat ambiguous, but if we consider the possibility that the enigmas that are already at play in Fauvel reach as far as the author figure (and remembering that in the earlier versions of the text the name of the author figure, Gervès du Bus, also appears as an enigma) we can add more evidence to support this view. For when I thought about this figure, "Mesire Chaillou de Pesstain", I realised that it in fact contains all the letters of "Charles de Valois". This would provide the link between Valois' involvement in the book's production and the clerks, such as Lalou's Chalop, whose name may have been corrupted from "Chalop de Persquen" to "Chaillou de Pesstain" with the intention of concealing, or containing, that of Valois. A suggestion, if one is needed, to complete the anagram could be "Charles de Valois si empeint" ("Charles de Valois is involved"):

According to Godefroy, in addition to the meaning suggested above, the verb "empeindre" can also mean "to hit someone" and in the reflexive it can mean "to throw oneself into something".[12] The possibility that this verb, with its overtones of violence and determination, completes the anagram is indeed only a possibility, but one that should not be overlooked in the context of the implication of Valois in the production of the satire. Also contained in the anagram, of course, is the name Chalop, as well as Jehan de Maillart, another notary-cum-writer who was also working in the royal chancery at this time, and who had hidden his name in an enigma in his Roman du Comte d'Anjou. |

| 11 | The very layout of the stanza which names Chaillou as author my suggest an anagram: It can be seen in figure 3 that the stanza in which the authorial naming takes place is incomplete: the letters <g> for Gervès (the first letter visible in figure 3) and the <C> beginning the rubric which names Chaillou are readable but look as though they were never entered in their final form, they appear to have been intended for some kind of illumination which never happened. However, as the presence of an anagram heralds the text as incomplete until the puzzle is solved, perhaps the "incomplete" stanza is here highlighting an incomplete naming in a manner which is as negative as any hidden anagram it may contain.[13] Therefore if this anagram was intended, it could be seen as part of what Emma Dillon called in her emailed response to my idea a "game of authorial subterfuge completely in keeping with the culture around the royal chancery". It also adds royal weight to Fauvel's satire. |

| 12 | As with the other anagrams we have looked at, the reader, in this case specifically the king Philip V, is invited to take an active part in the story and take the final step to its completion. In Fauvel, this final step is the most important of all, for the story is left unfinished: at the end of the story Fauvel, representing Marigny, is past his peak but not yet overthrown. What the authors are asking by leaving both the story and the naming incomplete is that Philip actively takes the final step to finish off Fauvel, and never to allow his minions to rule over him as Marigny had done over his father Philip IV. |

| 13 | So what we have seen here is the development of the author from near-anonymity to the feigned anonymity of anagrams. However no discussion of anagrams would be complete without its caveat. To solve an anagram, we first have to know what it is we are hoping to find. The danger, from this distance in time, is always that we can never know whether what we expect to find is what the work's first readers would have found or what was originally intended. With a figure such as Machaut, so clearly visible through his works, the game is a kind of authorial hide and seek.[14] The Livre de Fauvel is a book which is innovative in many ways already, and if this implication of Charles de Valois in its production was intended, then the anagram is here used in a unique way. For, although it is possible that Valois' part in the book's production may have been common knowledge, it is also possible that, unlike Machaut's games, Valois would actually want to hide behind a collective: he was out of favour with his nephew at the beginning of his reign, yet when Philip V allowed Marigny's body a decent burial and welcomed his relatives home from exile, Valois may well have felt compelled to deliver a warning, veiled or otherwise. All that we can do from this distance is speculate the extent to which this most innovative work influenced royal and artistic events, and to admire it as an example of how musica could be used to try and alter the course of history. |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

[1] J. Coleman, Public Reading and Reading Public in Late Medieval England and France (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996)

[2] Coleman, p. 112.

[3] Chrétien de Troyes, Erec et Enide, ed. J-M. Fritz, Lettres Gothiques (Paris: Livre de Poche, 1992), vv. 9-12, 23-26, trans. by Carleton W. Carroll in Arthurian romances / Chrétien de Troyes (London: Penguin, 1991), p. 37.

[4] S. Huot, From Song to Book: The Poetics of Writing in Old French Lyric and Narrative Poetry (Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 1987), pp. 47-48.

[5] Huot, p. 48.

[6] Huot, p. 83.

[7] L. de Looze, "Signing Off in the Middle Ages: Medieval Textuality and Strategies of Authorial Self-Naming", in A. N. Doane and Carol Braun Pasternack eds, Vox intexta: Orality and Textuality in the Middle Ages (University of Wisconsin Press, 1991), pp. 161-78 (pp. 175-76).

[8] Huot, pp. 39-40.

[9] L. de Looze, " 'Mon nom trouveras': A New Look at the Anagrams of Guillaume de Machaut - the Enigmas, Responses, and Solutions", The Romanic Review, 79 (1988), pp. 537-557 (p. 547).

[10] F. Godefroy, Dictionnaire de l'ancienne langue française et de tous ses dialectes du IXe au XVe siècle 10 vols (Paris: Vieweg, 1881 - 1902), vol. 3, pp. 735-6 and Lexique de l'ancien français (Paris: Librairie universitaire, française et étrangère, 1901), p. 227.

[11] See for example Le Roman de Fauvel in the Edition of Mesire Chaillou de Pesstain: A Reproduction in Facsimile of the Complete Manuscript, Paris, Bibliotèque Nationale, Fonds Français 146, ed. by Edward Roesner, François Avril and Nancy Freeman Regalado (New York: Broude Brothers, 1990), Introduction, and E. Dillon "The Profile of Philip V in the Music of Fauvel" and A. Wathey "Gervès du Bus, the Roman de Fauvel, and the Politics of the Later Capetian Court" in M. Bent and A. Wathey eds, Fauvel Studies, pp. 215-231 and 599-613.

[12] Godefroy, vol. 3, pp. 48-49.

[13] I am grateful to Elizabeth Era Leach for pointing this out to me.

[14] de Looze, "Signing Off", p. 170.

eSharp issue: spring 2004. © Kate Maxwell 2004. ISSN 1742-4542.