Spreading Protection: Exploring the Potential of Transmissible Vaccines to Safeguard Ecosystems

Published: 18 April 2024

An interesting new publication explores self-spreading vaccines to protect wildlife from deadly pathogens such as rabies. Megan Griffiths explains the complex interdisciplinary work behind this innovative technology.

Large-scale vaccination of most wild animals will require the development of new technologies that are compatible with the ethical and safety considerations of a variety of stakeholders. Self-disseminating or ‘transmissible’ vaccines are a potentially viable, but controversial option for to immunize wildlife at unprecedented scales. Here, an inter-sectorial group of researchers propose a series of commitments to advance our common goal of developing transmissible vaccines in a safe, equitable, and transparent manner.

Why should we vaccinate wild animals?

Vaccination has long been at the forefront of humanity’s fight against infection. For the most part, vaccines have been reserved for humans and companion animals to protect the health of the individual. However, the wildlife hosts of pathogens which can jump into and cause outbreaks in human and livestock populations (“spillover”) have been historically unreachable, offering a prime new target for vaccination. Reducing the number of infected hosts in a wildlife population could proactively reduce the threat and destructive consequences of virus spillover and could also serve to protect wildlife species threatened by pathogens. A key question, is how to deliver enough vaccines to wild animals to disrupt pathogen transmission. Transmissible vaccines that are designed to harnesses the natural replicative and self-spreading properties of carrier (“vector”) viruses may provide an answer.

How would a transmissible vaccine work?

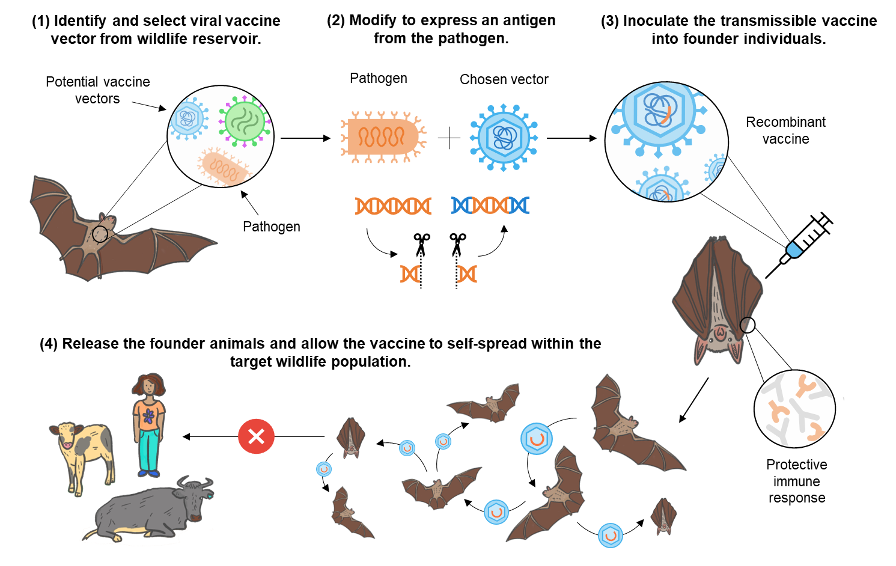

These vaccines propose to use a virus that naturally exists in the target wildlife population but that doesn’t cause serious disease and can’t infect species like humans or livestock. A section of genetic material from the target pathogen would be inserted into this vector virus – just enough to give the immune system something to respond to without adding any harmful properties. This vaccine would be given to a small number of captured animals which are then released back into the wild. Because the vector virus is unchanged apart from the small gene segment from the pathogen, it can behave as it would naturally: replicating in its host and transmitting onwards, vaccinating many more animals than could be reached directly.

What are the challenges involved?

Transmissible vaccines create enormous complexity. Researchers need to understand the ecology of the wildlife to be vaccinated, the pathogen, the vector virus, and the potential consequences of disturbing the natural balance between them. There are the technical aspects of engineering the vector to produce the pathogen antigen whilst maintaining its natural transmission, and safety and security responsibilities in ensuring that the vaccine only spreads within the target population. We also face regulatory uncertainties and ethical issues for a new technology that might cross international borders in some contexts of release. No one type of researcher has the expertise to solve or even fully understand all of these challenges. To address this, a diverse group from the fields of biology and social science, including both those in favour and critics of transmissible vaccines were brought together. The group discussed the potential risks and benefits during a 3-day workshop and presented a development framework to guide and encourage the future of transmissible vaccines.

First published: 18 April 2024

<< News

Read the paper: https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.adn3231

Find out more about the Streicker Lab: https://streickerlab.com/