Human-made materials could make up as much as half of some Scottish beaches

Published: 7 January 2026

The natural sands of beaches along the Firth of Forth are being mixed with significant amounts of human-made materials like bricks, concrete, glass and industrial waste, new research has revealed.

The natural sands of beaches along the Firth of Forth are being mixed with significant amounts of human-made materials like bricks, concrete, glass and industrial waste, new research has revealed.

A detailed survey of six beaches led by a team from the University of Glasgow has found that these mineral-based materials, known as anthropogenic geomaterials, now make up far more of the beach surface than previously realised.

A paper published by the team in the journal Sedimentology shows that up to half of the coarse sediments on Granton Beach near Edinburgh are comprised of anthropogenic materials.

On average, materials of human origin make up around 22% of the pebble-sized or above sediments on the beaches the team surveyed, with brick fragments being the most common at five of the sites. Granton was dominated instead by concrete.

The research shows for the first time the extent to which anthropogenic materials, swept from land into the Forth by the erosion of coastal industrial sites and infrastructure and the dumping of waste, have joined materials produced by natural processes on the region’s beaches.

The team say that the modification of the natural composition of the beaches is significant enough that it warrants a new scientific classification, suggesting that they be called ‘Anthropogenic Mixed Sand and Gravel’, or MSG-A beaches in the years ahead.

John MacDonald of the University of Glasgow’s School of Geographical & Earth Sciences, a co-author of the study, said: “Much of the world’s urbanised coast is made up of unconsolidated post-industrial and landfill materials. As climate change increases the frequency and magnitude of coastal storms, more human-made waste materials are likely to be mobilised and enter beach systems.”

The researchers warn that increased buildup of anthropogenic materials on and around Scotland’s beaches could have unpredictable effects in the years ahead, as climate change accelerates coastal erosion.

Professor Larissa Naylor, a co-author of the study, said: “Part of our jobs as geomorphologists is understanding how our coast works and how it will be affected by climate change. However, the world’s urban beaches have been far less studied than natural beach systems – we could only find 44 previous papers worldwide on this new type of beach when we began our work.

“We expect more and more anthropogenic materials to reach our beaches in the years ahead. Research like this casts new light on how human activity is affecting the natural world. It is vital in helping us to understand how our beaches are changing and better enabling us to manage our changing coasts.”

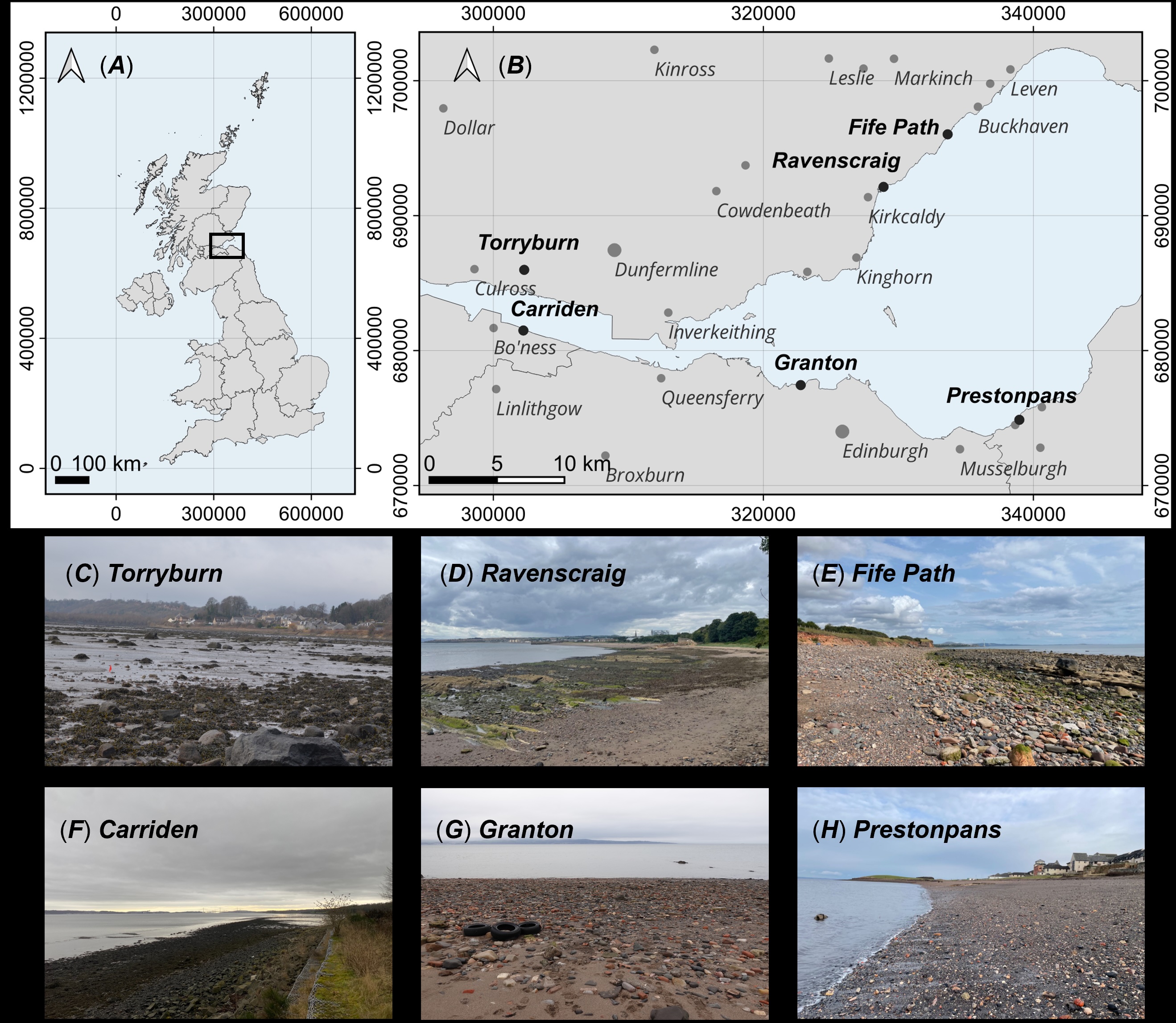

The team used a combination of physical surveys of beach sediments and aerial drone surveys to scrutinise the makeup of six sites representing different coastal conditions on the north and south sides of the Forth.

At Torryburn, Ravenscraig, and Fife Path on the north side, and Carriden, Granton, and Prestonpans on the south, they collected samples of beach materials at low, mid and high tides and identified the origins of the rocks, pebbles and grains they picked up. They also used drones to build up detailed 3D models of the terrain of each beach.

They found evidence of varying degrees of anthropogenic materials across the beaches, from 2% at Ravenscraig to nearly 49% at Granton’s mid-tide zone. They also discovered that, on average, 22% of the beaches’ coarse sediment fraction consisted of human-made material, including fragments measuring between 11mm up to 256mm.

However, very few were in the fine fraction below 11mm, suggesting that the materials are deposited into the Forth as larger fragments and have not yet been worn down by wave action, a conclusion supported by the team’s observation that more of the smaller fragments were found on beaches with higher wave energy.

Postgraduate researcher Yuchen Wang, who carried out the research as part of her PhD at the University of Glasgow, said: “This study is a vital first step towards building a complete picture of how Scotland’s beaches are being affected by the accretion of anthropogenic geomaterials. It’s very likely that if these six beaches have accumulated so much coarse sediment through human activity, others around the country and indeed around the world are likely to be similarly affected.

“We have already carried out repeated surveys of these beaches to track how they change over time, and how that change varies between more and less exposed sites.”

The team’s paper, titled ‘How natural are the sediments on our beaches? Characterising urban anthropogenic mixed beaches in Scotland’, is published in Sedimentology. The research was supported by funding from the China Scholarship Council, UKRI and the Scottish Alliance for Geoscience, Environment and Society (SAGES).

First published: 7 January 2026