Who do you think you are, Alex Graham?

Alex Graham dislikes authority. He strives for innovation and likes taking chances. But he always sticks to what he loves. The creator of television’s popular series Who Do You Think You Are? lets us in on his secrets to success.

Anyone who buys one third of a television production company for £1, as Alex Graham (MA 1977) did in 1987, then sells the whole company two decades later for £25 million, must have had their fair share of luck – the one personal quality to which the graduate readily admits.

‘I think about this often,’ he says. ‘Life is about luck as much as good judgement. You have to take your chances. Once I realised television was what I wanted to do I became more focused. I was passionate. I worked hard. But I never really had a plan.’

Early signs of high achievement, from the man who would produce one of the most successful TV programmes of all time – Who Do You Think You Are? – were not obvious. ‘My dad died when I was a boy and my mum went out to work,’ he says. ‘So my brother and I were latchkey kids. I remember my mum, when she got home, trying to encourage me to do my homework, saying “You’ll never get a proper job sitting around watching telly all day.”

He did, of course. But there were twists and turns along the way, the first during his time at the University, when Alex realised that in engineering he had chosen the wrong subject to study. Already well into his second year, he was struggling with the practical side, he says. ‘But it wasn’t easy to transfer to a totally different course. My best chance was to do really well in the end-of-year exams, I was told. That galvanised me. I worked like mad and in the autumn of 73 started back in first year, doing a Joint Honours degree in English literature and sociology.’

The power of paper

That ability to adapt was crucial, many years later, when his concept of Who Do You Think You Are? came in contact for the first time with reality. ‘I had thought of it as a different way of telling history,’ he says. ‘Each week would be about a big story, such as the First World War, told through the family history of a celebrity.’

That ability to adapt was crucial, many years later, when his concept of Who Do You Think You Are? came in contact for the first time with reality. ‘I had thought of it as a different way of telling history,’ he says. ‘Each week would be about a big story, such as the First World War, told through the family history of a celebrity.’

The first of these was Bill Oddie, whose family came from Rochdale and had worked in the cotton mills. ‘I thought we could use them to tell the story of the Industrial Revolution,’ Alex says. ‘But what interested Bill more was finding out why his mum had been away such a lot when he was growing up. He suspected mental illness.’

This sounded like a more interesting programme to Alex than his original concept, so he altered his thinking – rightly, as it turned out. ‘Our researchers discovered that Bill’s mum had given birth to a daughter who had died,’ he says. ‘There is a scene in that first episode when Bill gets the death certificate. It has a box pre-printed with the word “years”. Someone had scored that out and written “five days”. When Bill saw that it broke him up. It was very poignant. That’s when I realised this was a different kind of programme from what I had in mind. It was much more personal, more emotional.’

Alex himself gives the impression of being a calm, thoughtful man, whose emotions seem not so much kept in check as seldom stirred. ‘I do get quite emotional about all sorts of things – music, football, politics,’ he admits. ‘But in my day-to-day life I am logical and rational. Some would say relentlessly so.’

That clear-thinking quality is a necessary element in making good television, he says. But so too is something else – which comes with experience and maybe with all those hours watching TV as a boy. ‘You have to understand the language. If you want to work in France, you learn French. Television has a language too. It is not a good medium for complicated ideas. What it’s really good at is narrative and emotion. At those it is incredibly powerful.’

Entirely novel ideas are not as important as creativity of execution, he says. ‘Ideas are over-rated. Who Do You Think You Are? and The 1900 House are about as different as you could imagine. But what they both do is harness the strengths of television. I’ve always been interested in innovative ways of telling stories. My skill is in storytelling.’

Branching out

Alex’s own story, leading up to the foundation of the production company Wall to Wall, took him from the University of Glasgow into print journalism in London and Bradford, then, after a few years, to a researcher post at London Weekend Television. ‘I walked into the studios,’ he says. ‘And there was a moment when I looked around and remembered – this is what I wanted to do.’

But only four years later, following a rapid rise from researcher to series producer, Alex left London Weekend. The reasons are revealing. ‘It was a secure place with nice salaries and pensions,’ he says. ‘So most of my contemporaries stayed. But when Channel 4 came along in 1982, suddenly there were all these independent production companies. I was drawn to the small company culture.

‘I have always had a dislike of authority. I don’t like being told what to do. So I left to work for an independent production company called Diverse. I loved it and after four months I was running a prestigious current affairs programme.’

At this point chance took a hand again when Alex, now in his early thirties, met three young producers and went to work for the company they set up. ‘After a year I was offered a share in it,’ he says. ‘Nowadays production companies are seen as having real value. But in those days nobody knew. I bought a share in Wall to Wall for £1.’

Ten years later, in his mid-forties now, with three children under the age of 11, Alex had ‘a bit of a mid-life crisis’, he says, when the other directors moved on to big jobs in broadcasting and he was left in sole ownership. ‘I wondered if I’d missed the boat,’ he says. ‘But it didn’t last long. I knew by then I was a producer. I loved making television programmes and I was good at it. I realised I had all kinds of ideas about how they should be made and how companies should be run.’

An eye for talent

Choosing the right people and nurturing them is the key, he says. ‘I am proud of the programmes we made. I am almost more proud of the people we have had through Wall to Wall. The secret of success in any business, someone said, is to hire people more talented than you, then delegate more than you’re comfortable with. I have an eye for talented people and I delegate well.

Choosing the right people and nurturing them is the key, he says. ‘I am proud of the programmes we made. I am almost more proud of the people we have had through Wall to Wall. The secret of success in any business, someone said, is to hire people more talented than you, then delegate more than you’re comfortable with. I have an eye for talented people and I delegate well.

‘My mum taught me not to settle for second best. I’m committed to making things as good as they can be. It’s not exactly perfectionist. When I watch one of our films, I can always find something I wish we’d changed. Nothing is ever perfect. But if a thing is worth doing, it’s worth doing to the very best of your ability – that’s my mum again. I set high standards.’ Now in his early sixties, Alex does not give the impression of a man content to coast along, play golf and watch television. A sense of the drive that took him from Hamilton to the heart of London broadcasting remains. ‘We are in danger of getting into deep psychology here,’ he says. ‘But my dad died of meningitis when I was eight. That had an impact on me. Something has always driven me on. I worked long hours. I never wanted a nine to five job.’

The critical thinking he learned at Glasgow was vital, he says. ‘My years there were very formative. I worked hard and got a good degree. What I tell younwas vital, he says. ‘My years there were very formative. I worked hard and got a good degree. What I tell young people now is to choose a subject they’re passionate about, and don’t let the academic side completely define you. The stuff that really stuck with me was the theatre I did, and the music and the politics. And of course the people. University is about friendship.’

The final question, inevitably, is whether the man behind Who Do You Think You Are? has researched his own family history. ‘I haven’t,’ he admits. ‘I spent all my time doing other people’s. Genealogists tell me the process is as much fun as the result. So maybe now that I’m semi-retired I will have a go myself. It is on my bucket list.

‘I would like to find out who I am.’

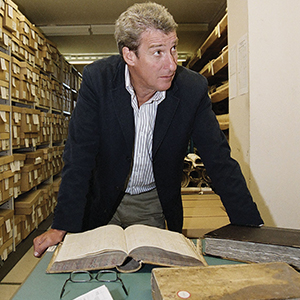

View your ancestors’ University records

Through the University’s archive services you can view your ancestors’ University records.

Students who graduated from the University, right back to 1451, left records of their study, which are now held in the University archives. Brief until the mid-19th century, these become more detailed from then on, and include matriculation records, prize lists, class roll books and records of student societies.

Archive services also hold records for Glasgow Veterinary College, Anderson’s College of Medicine, St Mungo’s College, Trinity College and Queen Margaret College.

Visitors can arrange to view records and do their own research. We recommend you make an appointment, so that a member of staff can explain the records to you. Remember to bring your camera.

Before your appointment, archives staff can find out, at no cost, if an ancestor studied at the University. They can be commissioned to carry out more detailed research.

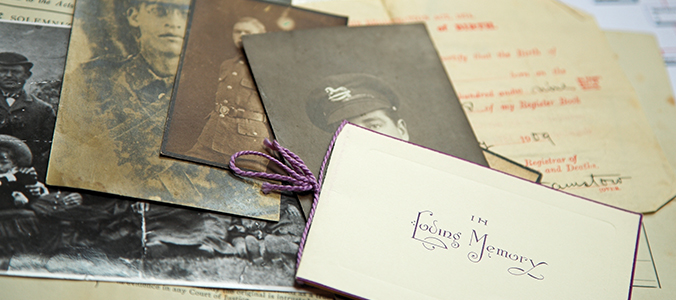

Researching your family history

- Make a note of what you and your relatives know. Don’t just talk to your older relatives; siblings and cousins may know something too.

- Start your family tree from the outset and keep it up to date. Try using a tree-building software package.

- Begin your search with the census in 1911, as you or your family will probably know of at least one relative living at that time.

- With this information you can order birth, marriage or death certificates (£9.25 each) or follow the family back to earlier censuses.

- Get help and advice from experts, such as from magazines, a local family history society or genealogy fair.

These tips are adapted from the Who Do You Think You Are? Magazine, which is filled with helpful tips and expert guidance on family research.

www.scotlandspeople.gov.uk is a good place to start for Scottish genealogical records.

Related links

- University's ancestral tourists service

- Who Do You Think You Are?