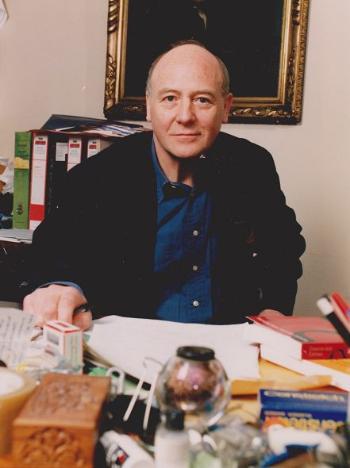

Robin Downie (19 April 1933—14 February 2023)

Published: 7 June 2023

Robin Downie, Emeritus Professor of Moral Philosophy, died on 14 February, 2023.

Robin Downie 19 April 1933—14 February 2023

Robin was born in Stepps, Lanarkshire, but his family moved to Glasgow when he was still very young. He attended the High School of Glasgow and then came to the University. Initially he thought of studying Music but a chance encounter with an introductory book on Philosophy led him to change his mind. He took honours in Philosophy and English and graduated with a first class degree. He then spent two years in the army as a national serviceman. He was assigned to the Intelligence Corps, which meant taking intensive training in Russian language. After demobilisation he moved to Oxford where he took the B. Phil. degree in Philosophy. In 1958 he married Eileen Flynn whom he had met during his undergraduate years in Glasgow. Together they had three daughters of whom Robin was immensely proud: Alison, Catherine and Barbara. Sadly Eileen died in 2017.

Robin was born in Stepps, Lanarkshire, but his family moved to Glasgow when he was still very young. He attended the High School of Glasgow and then came to the University. Initially he thought of studying Music but a chance encounter with an introductory book on Philosophy led him to change his mind. He took honours in Philosophy and English and graduated with a first class degree. He then spent two years in the army as a national serviceman. He was assigned to the Intelligence Corps, which meant taking intensive training in Russian language. After demobilisation he moved to Oxford where he took the B. Phil. degree in Philosophy. In 1958 he married Eileen Flynn whom he had met during his undergraduate years in Glasgow. Together they had three daughters of whom Robin was immensely proud: Alison, Catherine and Barbara. Sadly Eileen died in 2017.

Robin was appointed to a lectureship in Moral Philosophy in 1959. Ten years later he was appointed to the Moral Philosophy chair. He served as head of the Moral Philosophy Department until it was amalgamated with the Logic Department to form a single department of Philosophy. During that time he worked to increase the Department’s staffing and range of courses. He retired from the Chair in 2002 but continued to publish works of philosophy to the very end of his life. Central to virtually all of Robin’s philosophical activity was the conviction that Moral Philosophy has a direct relevance to everyday life. This was the underlying theme of much of his teaching and of his first three books, Government Action and Morality, Respect for Persons (co-authored with his Glasgow colleague Elizabeth Telfer) and Roles and Values. In these works he developed a view of ethics based on the Kantian notion of respect for persons. He argued that this can be seen as underpinning the liberal-democratic tradition in moral and political thought. He acknowledged that it might not apply so readily to other traditions but pointed to examples such as the United Nations Declaration of Human Rights which suggest that it could be more widely shared. These ideas underpinned much of his teaching in philosophy classes.

In most of his later work Robin sought to apply philosophical thinking to issues encountered in everyday life and to the work of various professions. These included education, social work, and, particularly, medicine and allied professions. Robin chaired a government committee which examined the teaching of values in social work courses. And was a member of one which

investigated the retention of organs. He established modules on values for the BN. Degree and also for the medical degree. He published a very large number of books and articles on topics related to medicine. Many of these were written in conjunction with medical colleagues. Among his co-authors was Fiona Randall with whom Robin wrote three books relating to issues in palliative care. During his final illness he was pleased to find that the consultant treating him was familiar with his work in this field. Another of his co-authors was Sir Kenneth Calman. Their joint publications included books on the ethics of health care and, most recently, a book on the quality of life, subtitled ‘a post-pandemic philosophy of medicine’. Robin also joined with Sir Kenneth in pioneering the field of medical humanities. His background in music and literature made him particularly well qualified for this.

Robin was always conscious that he was heir to a long and distinguished tradition of philosophy in Glasgow. He edited a selection of the works of Francis Hutcheson and published shorter pieces on Adam Smith. Among his very last publications were pieces in the Scottish Review about Smith and one of Glasgow’s other major philosophers, Thomas Reid. Robin was also conscious of the debt he owed to those who had taught him at the University, particularly William Maclagan and Bill Lamont.

Robin had many interests outside philosophy. In particular music was always a central part of life for him and for his family. He was particularly pleased that his daughter Barbara became a professional violinist. In the late 1970s he served as vice-president of the Glasgow University Union. The president at the time was Charles Kennedy who became an MP and leader of the Liberal Democrat Party. Charles was one of many students who found inspiration in Robin’s tutorials and stayed in touch with him. (See, also, the tribute to Robin by Andrew McIntyre in the Scottish Review). On a personal note I, too, am immensely grateful for the support and friendship he gave to me to other colleagues in Philosophy at Glasgow.

Richard Stalley

First published: 7 June 2023

Related links:

- Thomas Reid's Common Sense Method, published in the Scottish Review the day after his death.

- A remembrance of Robin Downie from a former student, published in the Scottish Review.