Stress is Cool

Published: 7 January 2015

Back to work after the holidays and feeling stressed out? We all know what it feels like to be stressed but how can we detect its in others, aside from being snapped at by a colleague at the water filter. How can we detect stress in animals?

Animals can't tell us when they are stressed but, for animals in our care, we would like to spare them from stress. Currently we rely on on assays of hormones that are associated with a stress response (mainly glucocorticoids). To do so we need to get a blood sample from the animal, although increasingly we can also sample this in other tissues like faeces, hair or feathers. Of course taking a blood sample of an animal is invasive and usually stressful, for both animal and researcher. There are also drawbacks with the interpretation of glucocorticoid data such as whether a raised level of glucocorticoid really always indicates stress or whether it sometimes indicates the opposite: for example glucocorticoid levels of a mouse that just lost a fight against a rival male are indistinguishable from the ones of a male that just mated. Thus we could really do with some alternative ways to measure stress.

When you have experienced stress you may have noticed some changes in the pattern in blood flow. Stress establishes a fright-flight response and makes us want to run away. In order to do so. In order to provide the necessary resources blood rushes to the core of the body to the central organs, and core body temperature raises. To measure this raised core body temperature of course we would need to resort to invasive techniques. However, the upside of warm blood rushing to core is that the surface of the animal is cooling. And that can be measured non-invasively using thermal images. And this is exactly what are doing here in Glasgow.

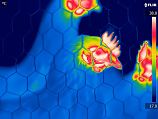

Thermal imaging picks up the heat emitted from an animal's body and we can record that basically whenever it is possible to film an animal. WE use mild stressor in order to elicit a small response in the animal. In a stressed animal the surface will cool down, because warm flood had been diverted to the core, and this can be quantified from a thermal image. This is best done for areas of the body where we can pick up the body heat from the surface and not where it is covered by hairs or feathers, for instances around the eyes.

Validation of thermal imaging as a measure of stress in domestic chicken:

A first step is to evaluate the usefulness of thermal imaging as a measure stress and this important work is done by Katherine Herborn on domestic chicken. Glucocorticoids have the nice property that their levels are proportional to the severity of the stressor; the more stressful an event is the higher should be the glucocorticoid levels. This also seems to be the case with the body temperature: the more severe an acute stressor the cooler the surface. Further work will also explore whether thermal imaging can also characterise chronic stress, which would be very valuable. There is also a final set of experiments planned to investigate whether thermal imaging may be able to differentiate between negative and positive experiences, something the glucocorticoids cannot do.

Application of thermal imaging in wild animals:

To step up the challenges, Paul Jerem has taken it on to record thermal images of wild blue tits, and investigates whether he can reliably detect changes in body temperatures in response to well established stressors. The first set of experiments on the response to an acute stressor (capture and handling) had been successful. Current work now looks at the response of wild blue tits that experience repeated simulated attacks by a stuffed sparrow hawk rushing towards them along a washing line, nicely capture in some recent footage by BBC Scotland.

First published: 7 January 2015