Castellani vs Bruce: the controversial discovery of the cause of sleeping sickness (2)

Published: 5 May 2021

In the second part of this series, Dr Federica Giordani relays the personality clashes and mistaken assumptions that dogged the first British Sleeping Sickness Commission - until a key observation was made.

The first British Sleeping Sickness Commission has arrived at the Uganda Protectorate with the aim to discover the cause of sleeping sickness, a deadly, mysterious disease that is decimating the local population. However, the three members of the commission will experience personality clashes and make incorrect hypotheses, until the day a corkscrew shaped parasite is discovered.

PART TWO

Barking up the wrong tree – Filaria worms and streptococci

Each member of the sleeping sickness commission had been assigned a specific task. Low and Christy were to research Manson’s hypothesis, which postulated a microfilarial worm was the responsible agent. Filaria perstans (now known as the harmless Mansonella perstans) had been discovered in 1891 by Manson himself in the blood of a West African sleeping sickness patient hospitalised in London. At the outset of the Ugandan outbreak the blood-worms were subsequently found in other individuals affected by the disease, seemingly supporting Manson's hypothesis.

Christy parted from his two colleagues immediately after reaching Kisumu, to undertake the first of his three journeys aimed at mapping the geographical distribution of sleeping sickness and Filaria perstans. He travelled alternately by foot and canoe into German East Africa (modern day Tanzania) to the east, and to the Congo Free State to the west, taking blood slides from people in every village he passed. He ended up stopping in Entebbe only for short rests in between his excursions.

In the most affected districts of the Busoga region Christy witnessed at first hand the misery inflicted by sleeping sickness. He described people walking only with the aid of friends or walking sticks or lying prostrated in the doorways of their huts. He found corpses along the way, empty huts and abandoned plantations. He described how locals, fearing contagion, abandoned the sick to their fate. Many villages had lost up to two-thirds of their inhabitants and half of those left behind had the disease[1].

During his investigations Christy noted that the areas where sleeping sickness thrived were wooded, tsetse fly-infested regions along the border of the lake and on the islands. However, further from the lake, the number of sleeping sickness cases dwindled - although Filaria perstans remained common in blood. This important observation allowed Christy to rule out Manson's original hypothesis: filarial worms most likely were not the cause of sleeping sickness.

In the meantime, Low and Castellani had stayed in Entebbe in a small laboratory set up in a native hut where they studied samples from local patients. Their workplace comprised a room divided in two by mats: half occupied by the microscope and the kerosene-operated incubator, while the other half was used for the preparation of culture media. The laboratory was connected to another hut, where they had established a hospital with separate wards for women and men. The hospital provided subjects and specimens for study, but little more than that. None of the patients who were admitted could be saved.

Low's data, together with those collected by Christy, further demonstrated that Manson’s worms were only randomly found in sleeping sickness cases leading the commission to discard the filarial theory. A disappointed Low left Uganda before the end of the mission, only six months after his arrival. He left orders for Christy to do the same once he returned from his latest wanderings in the field. Low went on to spend the rest of his career in London, working at the London School of Tropical Medicine and as a physician at the Hospital for Tropical Diseases[2]. Christy returned to Africa for a number of expeditions. He eventually died there, gored by a buffalo in the Belgian Congo in 1932.

Castellani’s expedition lasted longer and had more profound consequences. His original assignment had been to work on a possible bacterial origin of sleeping sickness. Pasteurian bacteriology was, by this time, a mature discipline and represented the classical paradigm for the study of germs in experimental medicine. Tropical Medicine was also rapidly expanding and the charismatic Manson, one of its major protagonists in Britain, was able to persuade the government of its value to the Empire.

At the same time as the British Commission was working in Uganda, another expedition, led by the Portuguese in Angola, was also looking for the underlying cause of sleeping sickness. Their work suggested that a diplo-streptococcal bacillus, named the “hypnococcus”, isolated from blood and cerebrospinal fluid of sleeping sickness patients, was playing a role[3]. Castellani, a trained bacteriologist, was aware of the results from the Portuguese sleeping sickness mission. After much painstaking work, the Italian also isolated streptococci from cerebrospinal fluid and cardiac blood of post-mortem sleeping sickness cases, as well as from a number of living patients with advanced disease. However, Castellani was convinced that his bacilli differed from those reported by the Portuguese and claimed to have discovered the real cause of the disease.

In October 1902 Low wrote a report to the Royal Society: “I have the honour to inform you with great satisfaction that Dr. Castellani has found a germ to be the cause of sleeping sickness. […] I have therefore proposed to Dr. Castellani that he should write a preliminary report on the organism for transmission home to the Royal Society [...] and I trust that the Society will at once see its way to publishing this note in the leading medical papers in England…”[4].

Castellani’s report was received coldly in London, where members of the Society considered his conclusion premature and dismissed the claims of this inexperienced, impudent foreigner. The decision was not to publish the preliminary note and to give Castellani six more months to confirm his results. Offended by the rejection, Castellani went on to publish his note in the Lancet in March 1903 without the approval of the Royal Society[5]. The mistrust sparked by the incident was soon to resurface in a series of events that followed.

A corkscrew shaped parasite

The bacillus hypothesis was destined to be short lived. During his investigations, Castellani had also found something other than bacteria in sleeping sickness patients. On the 12th November 1902, microscopical examination of the overlaying liquid (the “supernatant”) from a centrifuged sample of cerebrospinal fluid taken from a patient by lumbar puncture revealed a motile trypanosome. While this was the first time a trypanosome had been found in humans in East Africa, similar parasites had previously been observed in human blood in Western Africa in May 1901 by colonial service surgeon Robert Michael Forde working in The Gambia[6].

While treating a feverish master of the government steamer on the River Gambia, Forde had seen many motile, worm-like bodies in a fresh sample of his blood. The microorganisms had been subsequently identified by Joseph Everett Dutton, a young parasitologist from the newly founded Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, who had named the species Trypanosoma gambiense (now T. brucei gambiense, a subspecies causing the chronic form of sleeping sickness in West and Central Africa)[7]. The febrile illness caused by these parasites in West Africa became known as “trypanosoma fever”, and was considered then a mild infection, completely unrelated to sleeping sickness, the dreadful “negro lethargy”.

Prior to this discovery, trypanosomes had only been known to live in the bloodstream of animals and had been linked to the animal diseases surra, affecting horses and camels in India, and nagana, affecting cattle in Southern Africa. The name “trypanosoma” had been given to these flagellated microorganisms in 1843 by David Gruby, who wanted to reflect their corkscrew shape (“trupanon” in Greek means auger).

Dr Alexander Maxwell-Adams, another doctor working in the Gambia, had been asked for his views by Forde and wrote down his thoughts on the case. His notes reveal just how close he got to solving the puzzle. Maxwell-Adams proposed that transmission to men could occur through the bites of insects in much the same way as malaria was transmitted by mosquitoes. He recognised that the disease could also affect Europeans (contrary to the common view at the time that considered white people to be immune to the disease) and even wondered whether the trypanosome had any relation to sleeping sickness, suggesting that trypanosoma fever and sleeping sickness may be two phases of the same disease. He wrote: "Though the symptoms of the two diseases are different might they not be different stages of the same process -the first stage of the parasite circulating freely in the blood, in the second stage accumulating in the brain tissue, and so causing somnolency through local anaemia?"[8].

His intuition was ultimately correct, but his work was only published at the end of March 1903, by which time the Sleeping Sickness Commission was already hot on the tracks of the trypanosome.

The Second Sleeping Sickness Commission

By the middle of March 1903, working alone in his small laboratory, Castellani had found Trypanosoma parasites in the cerebrospinal fluid and in blood of some of the patients he was studying. Although these microorganisms were similar to those identified by Dutton in trypanosoma fever patients, he believed they belonged to a different species altogether, which he later named Trypanosoma ugandense.

However Castellani’s time in Africa was quickly running out and his research would soon be handed over to others. The Royal Society, dissatisfied with the lack of progress and aiming to probe more deeply into the streptococcus hypothesis, had dispatched a Second Commission.

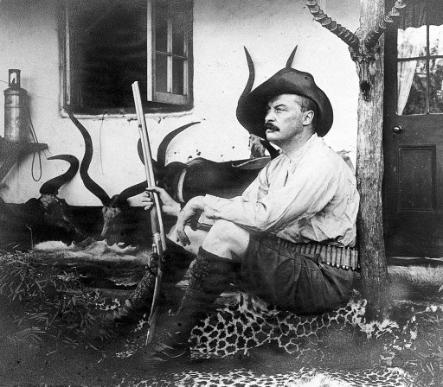

This new commission included two renowned investigators: pathologists David Nunes Nabarro and Col. David Bruce. Nabarro was a London-born son of a merchant who had undertaken a successful career as a surgeon. He was described as a modest and retiring person, beloved by his colleagues. His role in Uganda was to work on the clinical aspects of sleeping sickness. Bruce, conversely, was a Scottish army doctor with a taste for whisky and penchant for boxing. He had already made a name for himself by identifying the bacterium that caused Malta fever (Brucella). Perhaps more notably, he had discovered that trypanosomes were the cause of nagana disease in cattle (named Trypanosoma brucei after him), and found that transmission occurred via the tsetse fly. His wife, Lady Mary Elizabeth Bruce, accompanied him, acting as his laboratory assistant as was often the case.

Colonel David Bruce

Castellani had been informed that a new commission was on its way and he was instructed to communicate his work to Bruce and to follow his instructions. However, the Italian was still trying to publish his streptococcus note and was increasingly irate with the Royal Society’s conduct. Offended and lacking enthusiasm for the new commission, Castellani was evasive in his dealings with Bruce, even obstructive. Bruce, annoyed with the Italian’s lack of cooperation, complained to London that little work had been done in the preceding few months[9].

The Second Commission’s arrival in Entebbe, on 16 March 1903, was preceded by another dubious occurrence. Feeling under immense pressure, Castellani shared his findings regarding the trypanosome, allegedly under a “bond of secrecy”, with Moffatt and Clement John Baker, a Medical Officer in Entebbe9. Castellani’s revelation occurred after Baker had also seen trypanosomes in the blood of a feverish patient on 12 March 1903. While he had been examining a fresh blood film for possible malaria parasites he had seen “an elongated, actively motile body”[10] which he identified as a trypanosome, a diagnosis confirmed by Moffatt and Castellani. Other similar cases followed, but, incredibly, the connection with sleeping sickness remained elusive. The presence of trypanosoma fever among sleeping sickness patients had been shown and yet, possibly blinded by the desire to prove his original streptococcal hypothesis, Castellani refused to connect the two.

Castellani did eventually tell Bruce about his discovery of the trypanosome and the centrifugation method he had developed to isolate it from cerebrospinal fluid. Though ever secretive and conspiratorial, Castellani insisted that Bruce keep the revelation from Nabarro and allow the two men to work independently until the Italian’s departure; conditions Bruce accepted. The Italian also asked to stay in Entebbe for a few more weeks, during which time he and Bruce worked tirelessly seeking more evidence for the presence of trypanosomes in sleeping sickness patients. Trypanosomes were identified in 70% of cases, but never in controls. The streptococcus theory received further blows as other experiments failed to prove it.

Following his departure from Uganda (on the 6th April 1903), Castellani published his findings as sole author, seizing credit for the discovery[11]. In his account he suggested that trypanosomes were the causal organism of sleeping sickness but couldn’t quite bring himself to admit the streptococcal theory had been completely wrong, leaving open the possibility of germs having a secondary role in the pathogenesis of the disease.

He concluded his paper with the following statement: “I would suggest as a working hypothesis on which to base further investigation that sleeping sickness is due to the species of trypanosoma I have found in the cerebro-spinal fluid of the patients in this disease and that at least in the last stages there is a concomitant streptococcus infection which plays a certain part in the course of the disease”11.

FEDERICA GIORDANI

[1] Christy C. Sleeping sickness. Journal of the Royal African Society, 1903, 3:1-11

[2] Cook G C. George Carmichael Low FRCP: twelfth President of the Society and underrated pioneer of tropical medicine. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 1993, 87:355-60

[3] Amaral I. Bacteria or parasite? The controversy over the etiology of sleeping sickness and the Portuguese participation, 1898-1904. Hist Cienc Saude Manguinhos, 2012 19:1275-300

[4] Boyd J. Sleeping sickness. The Castellani-Bruce controversy. Notes Rec R Soc Lond 1973, 28:93-110

[5] Castellani A. The etiology of sleeping sickness (preliminary note). Lancet 161:1903 723-25

[6] Steverding D. The history of African trypanosomiasis. Parasit Vectors 2008, 1:3-10

[7] Dutton J E. Preliminary note upon a trypanosome occurring in the blood of a man. Thompson Yates Lab Rep 1902, 4:455-68

[8] Maxwell-Adams A. Trypanosomiasis and its cause. B M J 1903, 1:721-722

[9] Boyd J. Sleeping sickness. The Castellani-Bruce controversy. Notes Rec R Soc Lond 1973, 28:93-110

[10] Baker C J. Three cases of trypanosoma in man in Entebbe, Uganda. Br Med J 1903, 30:1254-6

[11] Castellani A. On the discovery of a species of trypanosoma in the cerebro-spinal fluid of cases of sleeping sickness. Lancet 1903, 161:1735-1736

*Image of the First Sleeping Sickness Commission from the Wellcome Collection (CC BY 4.0)

First published: 5 May 2021