What’s Left Out: Re-thinking the Abolition of the Slave Trade

Exclusion lies at the heart of curation. From the many hundreds, thousands or even millions of objects in a museum’s collection, people select very few to tell a story which might encompass multitudes. In the case of ‘Call and Response: The University of Glasgow and Slavery’, many items were considered and then left out.

From those left out, I have selected two in order to explain some elements of the curation of the exhibition, and also to talk a bit about the abolition of slavery. The story of abolition is one that is often told as a triumph of British exceptionalism. In recent years, the idea that the British Empire ‘ended slavery’ has taken hold in political discourse and finds its way into discussions of foreign policy, Brexit and national identity. The historical moment of abolition overshadows Britain’s two-century prominent role in enslaving Africans, forcibly transporting captives, and profiteering from slavery in the Americas and Caribbean.

This shadow is cast at the national level. When the bicentenary of the British government’s Abolition of the Slave Trade came around in 2007, celebrations frequently focused on individual British abolitionists at the expense of the history of Black resistance to slavery or the realities of how British people profited at the expense of Africans and people of African descent. Blindness to the history of British involvement of slavery finds its way into politics in many ways. For example, on BBC2’s Newsnight in 2011, as part of a longer racist diatribe, a commentator talked about how “this Jamaican patois that has been intruded in England”, a clearly nonsensical framing to anyone with even the most basic understanding of how Black people were transported to Jamaica by British enslavers. This deliberate misinterpretation is, in some ways, encouraged by a continued focus on abolition, rather than slavery.

For that reason, in this exhibition, two items relating to abolition were consciously set aside by the curators. In this post, I’d like to take the chance to give my response to these items as a historian of the abolition of slavery.

The first item might look familiar:

The obverse reads, ‘Whatsoever ye would that men should do to you do ye even so to them.’ A quotation of Matthew 7:12 from the King James Bible.

The design was originally conceived by Josiah Wedgewood, the famous potter, in the late 18th century and became the primary marketing tool and design for the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade. It was originally produced as a black and white cameo, but was reproduced in hundreds of media – in print, on fabric, on sugar bowls (most ironically). It was inlaid in gold on gentleman’s snuff-boxes. Thomas Clarkson, abolitionist campaigner and historian said,

At length, the taste for wearing them became general; and thus fashion, which usually confines itself to worthless things, was seen for once in the honourable office of promoting the cause of justice, humanity, and freedom.

It became a signal for society – I support this worthy cause, you should too.

However, it was very much a signal deployed by elite white society and it was designed specifically to make white audiences feel comfortable with the abolition cause. There’s little about purchasing a gold-plated snuff box inlaid with an image of a kneeling and supplicant enslaved man that challenges either the unequal distribution of wealth generated by slavery. White abolitionists regarded equality as something which they could bestow on Africans and people of African descent.

This symbol became ubiquitous, not only as part of the historical abolition campaigns, but also as part of exhibitions related to the 2007 bicentenary of the Act to Abolish the Slave Trade. Most museums were careful, though, to highlight how this object reinforced 18th-century notions of racial hierarchy in their interpretation. An example of that type of curation can be found here on Manchester Museums’ Revealing Histories: Remembering Slavery website,

Whilst it was intended perhaps to shame those who were involved in the slave trade, it also had the negative effect of representing the enslaved man as essentially passive. In fact, enslaved people repeatedly resisted oppression with courage, ingenuity and determination.

Enslaved people resisted enslavement in a myriad of different ways. They revolted aboard slave ships, around one in ten slaving voyages experienced major rebellions. Some ran from their enslavers, we can see the evidence of this for the UK at Runaway Slaves in Britain, a database of advertisements placed by British enslavers seeking their return. But most dramatically, in August 1791, when enslaved people on the French island colony of Sant-Domingue, rose against the slave masters and began the world-changing Haitian Revolution. The revolution overturned both the slavocracy and the colonial government. In 1804, the free republic of Haiti published its Declaration of Independence.

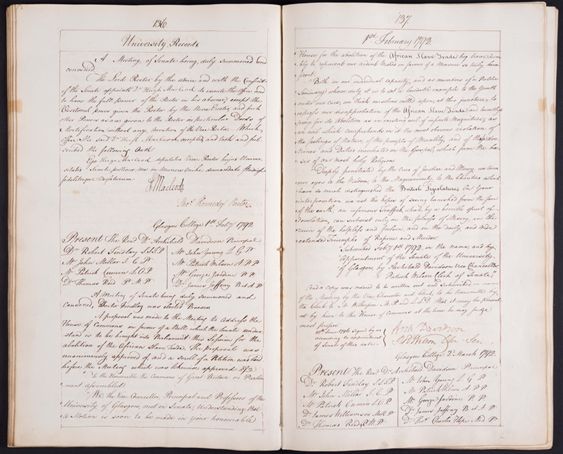

At the same time that enslaved women and men were fighting to end slavery and overthrow colonial rule in the Caribbean, the anti-slave trade movement was gathering momentum un Britain, including at the University of Glasgow. The second object that was considered and left out was the record of university’s own petition in support of the abolition of the slave trade.

This petition was written and presented to Parliament in 1791 in support of William Wilberforce’s second Bill to abolish the slave trade. The minute reads,

A proposal was made to the meeting to address the House of Commons in favour of a Bill which the Senate understand is to be brought into Parliament this session for the abolition of the African Slave Trade. The proposal was unanimously approved of, and a scroll of a Petition was laid before the meeting which was likewise approved of.

Professors with abolitionist leanings at the University of Glasgow in the 18th century included Francis Hutcheson, Professor of Moral Philosophy in 1730, Adam Smith Professor of Logic and Moral Philosophy 1751, and John Millar Regius Professor of Civil Law 1761. Present at the Council meeting of 1 February 1792 which approved the petition, were: Rev Dr Archibald Davidson (the Principal), Dr Robert Findlay, Mr John Millar, Mr Patrick Cumin, Dr Thomas Reid, Mr John Young, Mr Patrick Wilson, Mr George Jardine, and Dr James Jeffray. These sincere efforts to pressure the government to end the slave trade (though not slavery itself) have to be carefully put into the context of the ongoing revolution in Haiti. From the end of 1791, local Glasgow newspapers were reporting on the revolution and it was clear to most that the slave systems of the Caribbean were being brought to an end, by the slaves themselves.

The bill to abolish the slave trade in 1792 was passed, by 230 to 85, but with the devastating amendment that it should be enacted ‘gradually’. It was not until fifteen years later, and three years after the success of the Haitian Revolution, that an Act for the Abolition of the Slave Trade passed in Parliament. In the intervening period, 606,325 African men, women and children were forced on-board British slave ships. Only 547,397 survived the brutal ‘Middle Passage’ to face a shortened life of torture and forced labour. This is also vital context to the university petition. It would then be another generation before slavery itself was abolished in 1833.

In an attempt to win over an elite white audience, the largely white British slave trade abolition movement attempted to appeal to their audience’s ego – you too can be a great philanthropist and save your fellow man. Simply sign this petition, hand-out this pamphlet, wear this cameo brooch. They framed this activity as part of British national character – effectively deploying nationalist and patriotic sentiment about ‘what it means to be British’ for the anti-slave trade cause. However, in doing this they created a notion that something call Britishness is necessarily rooted in something called freedom. But if we looked to the reality of the British Empire in 1807 when the slave trade was abolished – freedom was hardly its defining feature.