Scientists discover how the atmosphere of Mars turned to stone

Published: 21 October 2013

Scientists may have discovered how Mars lost its early carbon dioxide-rich atmosphere to become the cold and arid planet we know today.

Scientists at the Scottish Universities Environmental Research Centre, the University of Glasgow and the Natural History Museum in London may have discovered how Mars lost its early carbon dioxide-rich atmosphere to become the cold and arid planet we know today. This research provides the first direct evidence from Mars of a process, called ‘carbonation’ which currently removes carbon dioxide from our own atmosphere, potentially combating climate change on Earth.

BBC Online: Meteorite may explain 'how Mars turned to stone'

It is widely recognised that accumulation of carbon dioxide in the Earth’s atmosphere is contributing to global warming. The loss of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere of Mars, however, around 4000 million years ago is likely to have caused the planet to cool. So understanding how carbon dioxide was removed from the Martian atmosphere could lead to new ways of reducing the accumulation of greenhouse gases in our own atmosphere.

In a paper published in the journal Nature Communications, the research team describe analyses of a Martian meteorite known as Lafayette, sourced from the research collections of the Natural History Museum in London and the Smithsonian Institution in Washington. It formed from molten rock around 1300 million years ago, and was blasted from the surface of Mars by a massive impact 11 million years ago. Since its discovery in Indiana, USA, in 1931, Lafayette has been studied by scientists around the world.

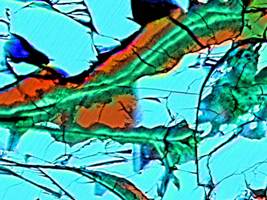

This research focused on a carbon-rich mineral called siderite. Although found in Lafayette previously, the team discovered that the siderite had formed by the process of ‘carbonation’, whereby water and carbon dioxide from the Martian atmosphere reacted with rocks containing the mineral olivine. These reactions then formed siderite crystals, replacing the olivine, and in so doing captured the atmospheric carbon dioxide and permanently stored it within the rock.

Lafayette provides direct evidence for storage of carbon dioxide in the fairly recent history of Mars, some time after 1300 million years. However as all of the ingredients for carbonation were present on early Mars, in the form of olivine, water and carbon dioxide, this reaction may explain how carbon dioxide was removed from the planet’s atmosphere changing its climate from warm, wet and hospitable to life, to cold, dry and hostile.

Whilst this process also occurs naturally on Earth, and is the focus of research examining methods of permanently locking up carbon dioxide from power stations, the magnitude of the effect on early Mars indicates that it has the potential to be effective on a planetary scale.

Dr Tim Tomkinson of the Scottish Universities Environmental Research Centre, Research Associate at the University of Glasgow and lead author of the paper, said “Mars once had a thick atmosphere that was rich in water and carbon dioxide, and so this process of carbonation may help answer the mystery of why the Martian climate deteriorated around 4000 million years ago.”

“This discovery is both significant in terms of the way in which scientists will study Mars in the future but also to providing us with vital clues to how we can limit the accumulation of carbon dioxide in the Earth’s atmosphere and so reduce climate change”.

Dr Caroline Smith, Curator of Meteorites at London's Natural History Museum, and co-author of the paper said, “Our findings show just how valuable meteorites from Museum collections like those we have here at the Natural History Museum really are. There is so much important and useful scientific information locked away in these rare rocks. Our study shows that as we learn more about our planetary next door neighbour, we are seeing more and more similarities with geological processes on Earth.”

The work was funded by the Science and Technology Facilities Council.

Related Links

- Dr Tim Tomkinson

- Scottish Universities Environmental Research Centre

- College of Science and Engineering

Image width: 124 µm.

Image credit: SUERC, University of Glasgow.

A copy an Optical image of Lafayette meteorite is available from the Natural History Museum, London collection. (contact details below).

For further information, contact Cara.macdowall@glasgow.ac.uk or call 0141 330 3683

For a full copy of the paper click here: http://www.nature.com/ncomms/2013/131022/ncomms3662/full/ncomms3662.html

Winner of Best of the Best in the Museums + Heritage Awards 2013, the Natural History Museum welcomes five million visitors a year. It is also a world-leading science research centre. Through its collections and scientific expertise it is helping to understand and maintain the diversity of the planet, with groundbreaking partnerships in more than 70 countries. For more information go to www.nhm.ac.uk.

For further information about the Natural History Museum or to interview Caroline Smith please contact the Museum Press Office

Tel: 020 7942 5654

Email: press@nhm.ac.uk

(not for publication)

First published: 21 October 2013

<< October