Nanokicking stem cells to open for new generation of orthopaedics

Published: 4 April 2013

New research has shown that it is possible to grow new bone by “nanokicking” stem cells 1,000 times per second using high frequency vibrations

New research has shown that it is possible to grow new bone by “nanokicking” stem cells 1,000 times per second using high frequency vibrations.

This new technique is cheaper and easier to implement than current technologies and it is hoped that it may lead to new therapies for orthopaedic conditions such as spinal traumas, osteoporosis and stress fractures.

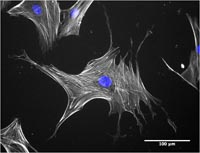

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSC) are naturally produced by the human body and have the potential to differentiate into a range of specialised cell types such as bone, cartilage, ligament, tendon and muscle. Scientists can isolate the mesenchymal stem cells and, by replicating environment cues that occur naturally within the body, grow specialised cells and new tissue in the laboratory.

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSC) are naturally produced by the human body and have the potential to differentiate into a range of specialised cell types such as bone, cartilage, ligament, tendon and muscle. Scientists can isolate the mesenchymal stem cells and, by replicating environment cues that occur naturally within the body, grow specialised cells and new tissue in the laboratory.

However, getting stem cells to differentiate correctly is notoriously difficult and current methods rely on expensive and highly engineered materials or complex cocktails of chemicals.

The team, led by researchers at the University of Glasgow, hope that nanokicking may lead to a fundamental change in the way that we grow new bone. This research also paves the way for future links with rehabilitation engineers in the Queen Elizabeth National Spinal Injuries Unit (Southern General Hospital, Glasgow) to help optimise whole body vibration therapy starting to be provided to patients with spinal injuries.

The team, led by researchers at the University of Glasgow, hope that nanokicking may lead to a fundamental change in the way that we grow new bone. This research also paves the way for future links with rehabilitation engineers in the Queen Elizabeth National Spinal Injuries Unit (Southern General Hospital, Glasgow) to help optimise whole body vibration therapy starting to be provided to patients with spinal injuries.

The new technique makes use of that fact that, when individual bone cells stick together to form new bone tissue, the cell membranes of each cell vibrate as they adhere. It is thought that vibrating the stem cells at this frequency encourages ‘communication’ between the cells and promotes bone formation. Scientists can replicate this vibration by ‘kicking’ the stem cells in the lab around 5-30 nanometres in distance 1,000 times a second.

The team measured the strength and frequency of the kicks using an incredibly precise measuring technique called laser interferometry which amongst other things is used to detect tiny ripples in space-time caused by gravitational waves. This project brings together cell engineers, Prof Adam Curtis and Dr Matthew Dalby at the University of Glasgow, and astrophysicist, Dr Stuart Reid at the University of the West of Scotland, in a unique collaboration of very different disciplines.

Dr Matt Dalby from the Centre for Cell Engineering at the University of Glasgow said: “This new observation provides a simple method of converting adult stem cells from the bone marrow into bone-making cells on a large scale without the use of cocktails of chemicals or recourse to challenging and complex engineering.

“Multidisciplinary research is tricky as researchers need to learn new scientific languages, however, this collaboration between cell biologists and astrophysicists – an unlikely pairing – has yielded new insight as to how bone stem cells work. We look forwards to working with the rehabilitation engineers; this will provide us with new challenges, but challenges that we welcome.

Dr Stuart Reid, of the University of the West of Scotland’s Thin Film Centre, said: "Linking stem cell research with expertise from the field of gravitational wave astronomy, where we have developed instrumentation that can measure length changes almost million times smaller than the diameter of a proton, have enabled this unique research field to emerge."

Dr Sylvie Coupaud, from the Department of Biomedical Engineering at the University of Strathclyde, said: "Movement is life; inactivity is a killer. Exercise is effective for maintaining bone health, but patients with reduced mobility typically have limited options for exercise and are at risk of developing brittle bones (osteoporosis) and associated fractures.

“Vibration therapy could be applied to stimulate bone formation and maintain bone health in these patients, as an alternative to traditional exercise. In the next phase of this bench-to-bedside research, parameters of vibration that have been shown by Dalby and Reid to successfully stimulate the development of bone cells in the lab can be scaled up for testing in patients to quantify their bone-stimulating effects in whole bones."

ENDS

Information for editors:

For more information and to arrange interviews, please contact Nick Wade in the University of Glasgow’s Media Relations Team at 0141 330 7126 or email nick.wade@glasgow.ac.uk.

- The Centre for Cell Engineering at the University of Glasgow is a collaboration between biologists, physical scientists, engineers and clinicians with the aim of understanding the cell / material interface and the micro / nano scale and then building improved and new medical devices.

- The Thin Film Centre at University of the West of Scotland has been operating for ten years and provides a unique service for industry in the research and development of deposition processes for thin films, design and fabrication of thin film products, characterisation of thin films and the dissemination of information about the applications of thin films.

The Centre collaborates with a wide range of industries and applications including ophthalmics, optics, telecoms, flexible displays, bio engineering, energy generation, decorative and barrier coatings for pharmaceutical and food products.

- The University of Strathclyde is a leading international technological university which is recognised for strong research links with business and industry, commitment to enterprise and skills development, and knowledge sharing with the private and public sectors. The University was named UK University of the Year in the 2012 Times Higher Education Awards. More at www.strath.ac.uk

First published: 4 April 2013

<< April