Chitral - A Hidden Paradise of the Hindu Kush

© Photograph Copyright Azra and Peter Meadows.

Upper Chitral Valley. Photograph taken during summer 1999 on the International Hindu Kush Expedition.

Evening Discussion Meeting

On

Chitral

and

The 1999 International Hindu Kush Expedition

Linnean Society of London, Burlington House, Piccadilly, London.

23rd November 2000

An evening discussion meeting of the Linnean Society organised by

Azra and Peter Meadows, University of Glasgow.

Chitral

The Chitral region of the Hindu Kush in Pakistan is one of the most isolated areas of the western end of the Himalayas, and is surrounded by high mountain passes. It is also one of extreme beauty. The remote human communities, which include the Kalasha, live in narrow valleys dominated by mountain rivers and natural hazards, and prehistoric sites abound. Chitral's biodiversity is unique, and many of the passes are migration routes between central Asia and the Indian subcontinent.

The Evening Discussion Meeting at the Linnean Society of London

The meeting reported current explorations in Chitral and the initial results of the 40 member RGS International Hindu Kush Expedition which scientifically explored Chitral in summer 1999, led by Peter and Azra Meadows University of Glasgow and by Professor Israr-ud-Din University of Peshawar.

The meeting also acted as a forum for planning future initiatives in the area.

Chairman

Sir David Smith FRS, FRSE, President of the Linnean Society

Programme

18.00

Azra Meadows and Peter Meadows. University of Glasgow UK

Introduction.

Michael Bishop. University of Nebraska at Omaha, USA.

Remote Sensing Science and Technology for Landscape Assessment in the Hindu Kush.

Fred Naggs. Natural History Museum, London. UK

Faunal limits of land snail distributions in South Asia. From Chitral to Arunachal Pradesh and Sri Lanka

Ruth Young. University of Leicester. UK

New Archaeological Exploration in the Chitral Valley, Pakistan: An Extension of the Gandharan Grave Culture

Ihsan Ali. University of Peshawar. NWFP, Pakistan

Contributions of Hindu Kush Expedition and the Future of Chitral Archaeology

Tom Roberts. Anglesey. UK

Wild life of Chitral

Raymond Stoddart. University of Glasgow. UK

Intestinal Helminth Infections in Primary Schoolchildren from the Chitral and Kalash Regions of North West Pakistan

Peter Parkes. University of Kent. UK

The Kalasha. Current Research.

Saifullah Jan. Rumbur Valley, Chitral, NWFP, Pakistan

The Kalasha. An Indigenous View.

Sir Nicholas Barrington KCMG, CVO.

Conclusion

Reception

20.15

Reception in the Linnean Society Library. Poster Displays of work in Chitral.

The following are abstracts of some of the talks given at the meeting. They are the copyright of the individual authors. The abstracts will be shortly issued as a pamphlet.

Introduction

Azra Meadows, Peter Meadows.

Chitral lies in the isolated region of the Hindu Kush, at an altitude of 1500m upwards in the North West Frontier Province of Pakistan, on the border with Afghanistan. The four great mountain chains in Asia are formed from the Hindu Kush, Pamir, Karakoram, and the Himalyas. The highest peak of the Hindu Kush is Tirich Mir 7,787m. Mountain glaciers play a significant role in shaping these valleys, together with weathering, erosion and tectonic uplift, and also the effect of earthquakes, landslides and flash floods. Glaciers can be creative - as a source of irrigation or destructive - leading to loss of agricultural land, roads, and houses. A number of mountain passes surround the Chitral valley. There have been political and social links between the upper valleys and communities surrounding them across these high mountain passes. Historically the Chitral valley was one of the main arteries of the Silk Road across the Barogil pass to Yarkand and Kashgar in China. The Lowari Pass (3,118m) is the southern and the Shandur Pass (3,734m) the northern gateway to Chitral by road. The road journey from Peshawar takes about 12 hours. These land routes are inaccessible during winter and road access is through Afghanistan. Pakistan International Airline foker flights to Chitral take three quarters of an hour from Peshawar and are weather dependent.

The river systems of Chitral cover a total area of about 300km and all the vegetation and human settlements in Chitral depend directly or indirectly on them. The Yarkhun river in the north east joins the Laspur river further south near Mastuj to form the Mastuj river. The latter flows south to join the Lutkho river from the west. The Lutkho river is fed by the Tirich Mir glacier. The Mastuj and Lutkho rivers combine to form the Chitral river which flows through Chitral Town. At this stage the plain of the Chitral river is 4km wide with cultivated alluvial fans. As the Chitral river flows further south it becomes the Kunar river and is joined by the Ayun river from the west, which in turn is fed by the narrow rivers of Rumbur, Bumburet and Birir valleys. The Ayun valley is famous for its fertile land and lush vegetation. The Kunar river winds its way west into Afghanistan where it joins the Kabul river and eventually re-enters Pakistan and joins the Indus river at the historic city of Attock.

The known history of Chitral started with the Tibetans invading Yasin in the 8th century AD, followed by the Chinese in 750 AD, who were defeated by the Arabs. Bhuddists followed in 900th AD. Chitral became a unified independent kingdom in the 14th century led by Shah Nasir Rais. The Rais dynasty ended in 1570 and was replaced by the Kator dynasty. The first Mehtar of Chitral, Aman-ul-Mulk ruled from 1857 to 1892. In 1895 the Great Siege of Chitral Fort took place and lasted a month in which the Nizam-ul-Mulk was killed by his half brother. In 1947 the Mehtar Amir-ul-Mulk acceded to the Government of Pakistan but stayed in charge of the internal affairs. The Government of Pakistan was represented by a Political Agent. In 1954 there was internal revolt against the Mehtar and the Political Agent took over control in Chitral. It was in 1969 that Chitral State formally merged into Pakistan, in the District of Malakand and the Division NWFP.

The Chitrali people call their land "Kho" and their language is called Khowar. The majority are Sunni Muslims, although there are a number of Ismailis - followers of the Agha Khan. The minorities in Chitral are the Wakhi (in the Pamirs) and Kalash (in the Kalash valleys). A typical Chitrali household consists of a joint family system, with parents, sons, wives, single daughters and grandchildren living under one roof, with tight family bonds.

Agriculture is the main occupation of the Chitralis and irrigation is highly developed with gravity flow channels, sometimes referred to as "siphon irrigation". The winter crops are wheat and barley and the summer crops are maize and rice, with fruit and vegetable also grown. Terracing on steep slopes is normally practised with small water channels for irrigation. Any land which is less than 45 degrees angle is termed as level land in Chitral, and there is a major problem of soil erosion because of the steep slopes. Water also plays a vital role in the lives of the locals for example water grinding mills, Hydel power generators such as the new Reshun Hydro Power station and the number of mini-hydel power stations.

With this background a multidisciplinary International Hindu Kush Expedition to Chitral took place during mid July to mid September 1999. This expedition was largely funded by the Ralph Brown Expedition Award of the Royal Geographical Society of London and the Institute of British Geographers (see acknowledgements below for other funding bodies). The expedition leaders were Mr Peter S. Meadows and Dr Azra Meadows of Glasgow University, UK and Professor Israr Uddin of Peshawar University, Pakistan. There were a total of forty participants from twelve UK, Pakistan, and USA teaching and research institutions. The main objectives of the expedition were to study the impacts of mountain rivers on rural communities and the environment in Chitral, Hindu Kush. The expedition concentrated on the narrow river valleys (100 - 800m) Garam Chashma, Bumburet, and Rumbur and the broad river valleys (1-4km) Chitral and Mastuj. The expedition was divided into four main groups.

- Group 1: River function, natural hazards and biodiversity. River profiles, water flow and sediment load, flash floods, mud slides and avalanches, plant and animal communities.

- Group 2. Present day human settlements. Social organisation, health and gender issues agriculture, dependence on irrigation and rivers, domestic water use.

- Group 3: Prehistoric and historic human settlements, site distribution hierarchies, social organisation, subsistence, relation to present and past rivers and irrigation patterns.

- Group 4: Geomorphology - land form and use, housing, roads and bridges, irrigation and river terraces, and Landsat TM satellite imagery of Chitral including GIS.

During the expedition access to sites was by four wheel drive transport driven by expert local drivers. Accommodation for participants was arranged at the Chitral Area Development Project complex in Denin across the river from Chitral Town. In addition to the scientific methodologies used during the expedition a series of interviews with local village communities were carried out by members of the expedition from the four groups. Informal talks were given to local school children about the expedition, as well as intra-expedition talks were held for the expedition party.

The intended outputs of the expedition were as follows.

(i) Interaction between expedition members, including training of Pakistani members in state-of-the-art methodologies used by overseas members during field work

(ii) Overseas members learning of the problems of working in isolated and hazardous environments..

(iii) International academic and multi-disciplinary collaboration leading to future longer term research and teaching projects.

(iv) Encouragement of local communities in terms of community participation and capacity building, understanding and managing their natural resources and the unique nature and global significance of Chitral.

(v) Increasing the awareness of local communities to the mechanisms of natural hazards, their consequences and avoidance.

(vi) The holding of an international symposium in 2001 on the expedition findings and associated topics in Chitral.

With this background the evening meeting at the Linnean Society on "Chitral - a Hidden Paradise of the Hindu Kush" provided a forum for those interested in this unique environment, to meet and discuss past, present and future activities associated with the region and its people. Preliminary results of the 1999 International Hindu Kush Expedition were presented by participants at meeting. It was also a good opportunity for some of the participants of the Hindu Kush Expedition to meet for the first time because they were on different legs of the expedition. We would be delighted and grateful for any support, suggestions and advice for the 2001 symposium in Chitral and associated initiatives.

Acknowledgements

The organisers of the meeting (AM and PSM) are most grateful to: the Royal Geographical Society of London (Ralph Brown Expedition Award) and the Institute of British Geographers, the Lloyd Binns Bequest, the Glasgow Natural History Society, the John Robertson Bequest, the Percy Sladen Memorial Fund and the Linnean Society of London for funding the expedition, the University of Glasgow and the University of Peshawar for their support, and to the Linnean Society of London for hosting this meeting and for looking after the speakers. At the Linnean Society, we are especially grateful to Dr John Marsden, Executive Secretary, for his continuing support of our work. We are extremely thankful to the UK and overseas speakers and contributors for their oral and poster presentations and to the distinguished guests and Fellows of the Linnean Society for their interest and participation in the meeting.

© Photograph Copyright Azra and Peter Meadows

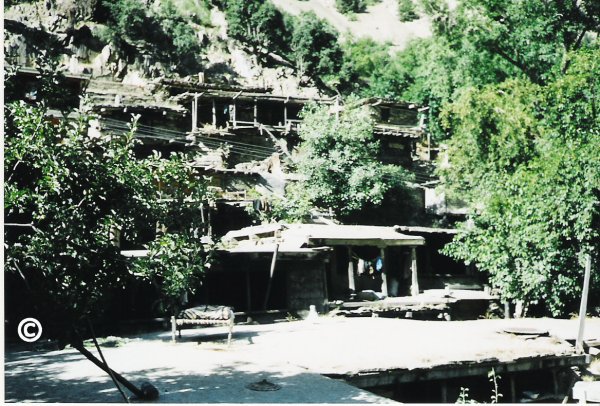

Traditional Kalash houses on a steep slope in the narrow Kalash valley of Rumbur, Chitral.

Photograph taken in 1997.

See abstract by Saifullah Jan. The Kalasha: Indigenous Perspectives

Remote Sensing Science and Technology for Landscape Assessment in the Hindu Kush

Michael P. Bishop

Department of Geography and GeologyUniversity of Nebraska at Omaha

Email bishop@data.unomaha.edu

High-mountain environments are the result of complex interactions between climate, tectonic and surface processes. Currently, we do not understand dynamic feedback mechanisms that control process rates and topographic evolution. Furthermore, limited information is available for most remote high-mountain environments because of geopolitical and logistic difficulties. Consequently, there is a need to utilize technology to develop operational models that can provide accurate information for scientific inquiry, resource assessment and hazard potential.The 1999 Hindu Kush expedition focused on the Chitral region in northern Pakistan. The objectives were to integrate geographic information science and geoscience investigations to better understand the geomorphology of the area. Specifically, scientific and monitoring objectives were to study the influence of surface processes on topographic evolution, examine the influence of climate forcing on alpine glaciation, and develop and test operational models using satellite imagery for landscape assessment. Our methodological procedures involved the use of global positioning system (GPS) technology for field mapping and data collection. We also analyzed multispectral satellite imagery from sensors aboard the Landsat-7 and Terra satellites. Topographic information was extracted from satellite data to produce digital elevation models (DEMs). Satellite imagery was draped over DEMs and computer scientific visualization software simulated flying through the landscape to examine remote areas and geomorphic features of interest. These simulations and 3-D perspectives of the landscape enabled us to assess land cover characteristics, identify active surface processes, and locate potential hazard risks. We also examined the geomorphometric characteristics of the landscape, which helped us to study the relationships between surface processes and landform development. Satellite and climatic data clearly depict a regional climatic gradient over the Chitral region, with greater aridity to the north. Altitudinal climate gradients also exist and vegetation patterns are strongly controlled by the topography and availability of moisture. Vegetation patterns in satellite imagery can be used to distinguish between natural versus agricultural vegetation in most valleys.Field investigations and computer analysis of satellite data indicate that glaciation has had a significant influence on the landscape. Large glaciers flowed over the landscape at higher altitudes in the past, dramatically influencing the nature of the topography. Although we do not have any dates associated with these glacial advances, we suspect that the southwestern monsoon is responsible for numerous glaciations, which would have accelerated deep valley erosion. Topographic evidence of a major glaciation was found at an altitude of approximately 4300 m near Tirich Mir, where an erosion surface exhibits extremely shallow slope angles. Periodic glacial advances and retreats produced large U-shaped valleys that are now occupied by villagers.

Our analysis of modern-day alpine glaciers suggests that many glaciers may be downwasting and retreating. More work is needed to confirm this and determine the regional trend, although evidence includes large supra-glacial lakes, disconnected tributary glaciers, and the occurrence of glacier outburst floods in numerous valleys. Glacier terminus configurations and positions also support the notion of glacial retreat in this region. Temporal analysis of satellite imagery and mass balance modeling is required to verify this.Alpine glaciers directly and indirectly respond to climate forcing. Satellite data indicate that most alpine glaciers exhibit a melt-water stream due to ablation. The availability of water at high-altitude represents an important resource to local villagers and the region, as irrigation systems are required to facilitate agriculture. Climate forcing and increased ablation at high- altitude, however, represents a significant natural hazard. We found numerous instances of high-altitude valley lakes where large landslides, probably caused by seismic activity, dammed the entire valley. These lakes can be extremely large in large glaciated valleys, as water volumes rapidly increase due to abundant glacier meltwater. Catastrophic flooding is initiated when the lake level reaches the top of the dam. We also found numerous instances of valley lakes produced by glacier damming. Satellite data can easily be used to identify large lakes and assess hazard potential.Collectively, our results indicate that surface processes in the Hindu Kush are extremely active.The water resource and hazard potential of the region is closely related to climate forcing. Given a global warming scenario, we might expect a water resource crisis and an increase in the natural hazard potential, as alpine glaciers adjust to negative mass-balance and fluvial activity at high-altitude is enhanced. In addition, operational monitoring of high-mountain environments from space is feasible, although more field data is required to verify remote sensing models and computer simulations.

New Archaeological Exploration in the Chitral Valley, Pakistan: An Extension of the Gandharan Grave Culture

R. Young 1; R. Coningham 2; C. Batt 2; I. Ali 3

1 School of Archaeological Studies, University of Leicester, UK

email: rly3@le.ac.uk

2 Department of Archaeological Sciences, University of Bradford, UK

email r.a.e.coningham@bradford.ac.uk

email c.m.batt@bradford.ac.uk

3 Department of Archaeology, University of Peshawar, Pakistan

Email ihsan@arch.pwr.sdnpk.undp.org

The Gandharan Grave Culture is the name given by many researchers to the pre- and proto-historic cemetery sites that were first recorded and explored in an area approximately corresponding to ancient Gandhara, the easternmost province of the Persian Empire. These sites have since been found in the valleys of Swat, Dir and Buner, as well as to the south in the Vale of Peshawar. At all these locations, strong similarities in grave construction, (which is primarily the use of large slabs of stone to create a rectangular cist grave), grave goods such as pottery, and also in the burials themselves, whether interments or cremations suggest that they belong to a similar cultural group.These Gandharan Grave sites, and associated occupation sites, are very important in terms of understanding the nature of archaeology and change in this region between c. 1700 – 500 BC. The Gandharan Grave Culture has thus been interpreted as representing a new, intrusive group of people bringing new burial customs and goods with them. However, it has also been suggested that careful examination of the material remains, such as the pottery and tools, and the grave construction, placement and burial styles in fact show change over time, and are therefore representative of indigenous development of existing groups rather than any incoming, invasive group. In Swat in particular, where there is a greater number of occupation sites, Professor Stacul (1997) has been able to link this to other archaeological evidence for population increase and new settlements within the valley.Professor Stacul (1969) recorded the presence of Gandharan Grave sites in Chitral as early as 1969, however, field work here has been very limited. Indeed, beyond one brief season of work looking at cemetery sites, little else has been published. Professor Allchin (1970) examined three ceramic vessels from Ayun, which he reported to have very close affinities with Gandharan Grave pottery types. Other scholars and travellers have noted the presence of Buddhist and later monuments, and there has been some research into the Islamic history of Chitral. Nevertheless, the study of early historic, proto-historic and pre-historic periods is limited. What has been uncovered to date, from the Gandharan Grave sites and the other archaeological remains supports the valley’s role as an important corridor of communication through the Hindu Kush. The new archaeological sites recorded in the 1999 season were located by field survey and the use of local knowledge of structures and graves in the landscape. There was considerable and detailed local knowledge available, particularly from farmers, and this is an excellent method for making an initial assessment of the type and density of recognisable archaeology in an area so little explored. A gazetteer of the new sites will be published shortly, giving further details. In all, eighteen sites were surveyed, and the number of Gandharan Grave Culture sites known in this region was doubled. The identification of what are believed to be Gandharan Graves in Chitral has important implications not only for the history and prehistory of Chitral itself, but also for the whole of this region of Pakistan. The results of on field season are significant. There is a density of archaeological remains that clearly shows the need for more work.

Bibliography

Allchin, F.R. 1970. A pottery group from Ayun, Chitral. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 23.1: 1-4.

Stacul, G. 1969. Discovery of Protohistoric Cemeteries on the Chitral Valley (West Pakistan). East & West 19: 92-99.

Stacul, G. 1997. Early Iron Age in Swat: Development or Intrusion? in R. Allchin & B. Allchin (eds), South Asian Archaeology, 1995: 341-348. New Delhi: Oxford & IBH Publishing Co. Pvt. Ltd.

Contributions of Hindu Kush Expedition and the Future of Chitral Archaeology

Ihsan Ali

Department of Archaeology, University of Peshawar, Pakistan

Email ihsan@arch.pwr.sdnpk.undp.org

The Chitral Region of Pakistan is rarely explored Archaeologically except for a brief reference by the Italian Archaeologist Professor Stacul and British Archaeologists Bridget and Raymond Allchin in the sixties, who referred to the Burials of Gandhara Grave Culture in the Lower Chitral. Though there are a few other brief references to the Culture and past history of Chitral, including the visit of Alexander the Great, but no serious research was conducted before the Hindu Kush expedition, at least in Archaeology, if not in other subjects. And therefore, our expedition has taken the first serious step to lay the foundations of Chitral Archaeology.

The sites we discovered during the 1999 expedition (in collaboration with Bradford University) and the ones in 2000 with Peter and Azra Meadows are mainly of two types.

1. Sites of Gandhara Grave Culture (Protohistoric Period)

2. Forts and settlement sites of the 17th-19th centuries

Though there was one Megalithic Burial Site also.

The Grave Period Sites are very important in terms of its geographical and archaeological value. The term Gandhara Grave Culture was introduced by Professor Dani of the University of Peshawar when he excavated the burial site at Timargarha in Dir District and Thana in Swat in the early sixties. Later, such burials were exposed in Swat by the Italian Archaeological Mission to Pakistan, led by Professor Stacul. These burials with extended, inhumated burials, urn burials (burials in jars) and fractional burials were buried single or multiple with grave goods and were dated by Dani to a period between 1800 and 600 B.C. and belonging to the Aryans, who, to many scholars were responsible for the decline of the Indus Valley Civilization. Infact, this burial culture has filled the gap between the decline of Indus Valley Civilization and the arrival of Achaemenian in 600 B.C. and were thus of great significance to Pakistan Archaeology. Later on such graves were also reported from the Peshawar Valley by Mr. Gulzar Khan of the Archaeology from Zarif Kaurona in the seventies and more recently by this author during the survey of the Peshawar Plain in 1996-97. Further, such graves are also reported from Bajaur Agency. But the important part of these discoveries is the origin, routes and geographical limits, which has been pushed forward by Chitral discoveries. The discovery of these graves put a question to the term Gandhara Graves because Chitral was never part of Ancient Gandhara. Also, their discovery in such a good number (as we know from a limited survey) hints to their arrival from the surrounding regions, which still needs to be thoroughly investigated. In addition to the above, the excavation of these burial sites, will certainly provide us a clue to the origin of the arrival date of the burials in addition to the provision of the antiquity for the Chitral Museum, which the Government of NWFP has already approved the their annual development scheme.

The remains of the historic period and survey of the other settlement sites will add to our knowledge regarding the chronological events taken place in the historical period, including the Greeks (particularly Alexander the Great) and the Kalasha .

The single known site of the megalithic Burials will throw light on the Megalithic sites, which is a subject rarely studied in this part of the world, though there a few such sites known from Peshawar, Gilgat and Karachi areas.

The discoveries of 34 sites (sofar) in Chitral by the Hindu Kush Expedetion are thus of great potential for furthering our knowledge regarding the past of Chitral, understanding the surrounding regions, clearing our previous concepts and preserving and protecting the archaeology and ethnology of Chitral (including the Kalasha) and exhibiting these antiquities in the Chitral Museum for lay man, scholars, researchers and tourists. I am happy to acknowledge the contributions of Meadows, the Linnean Society, London and my other colleagues in archaeology and other disciplins and congratulate them for laying the basis of a serious research in Chitral

Wild life of Chitral

Tom Roberts

The wildlife Chitral in the far north western corner of Pakistan is dependant on the area's physical geography. Chitral is a mixture of massive mountain peaks and steep-sided valleys, bounded in the north by the Hindu Kush range - whose highest mountain is the 25,320 ft high Tirich Mir. The climate is harsh. In summer temperatures often exceed 35° C, and in winter they can fall to -20° C in January with much snow in the higher altitudes. Rainfall, with snow is low - usually less than 32 cm per year, with most falling in winter. There is no monsoon.

The diversity of plant and animal fauna reflects this great variation in altitude and temperature, with its wide range of attendant micro-habitats. Forest cover is limited to patches, mainly in the more sheltered valleys. At lower altitudes this consists of the Holly Oak (Quercus ilex sub.sp. baloot), and higher up the Indian Cedar (Cedrus deodara), with the beautiful Edible Nut Pine or Chilghoza (Pinus gerardiana). At higher altitudes only the Himalayan Birch (Betula utilis) and the creeping juniper (Juniperus communis) are found - the former being mainly confined to ravines. The highest alpine meadows bear a wealth of Sedge species, and bulbous Lilieacae such as Allium spp. and Gagea spp. There are over 52 species of Astragalus recorded from Chitral, and the lower mountain slopes are covered by clumps of Artemisia, with a few wild Rhubarb (Rheum emodi) with its large crumpled leaves. The slow growing and closely grained timber of the Deodar is resistant to insect attack and is easily worked. It is therefore favoured for construction of door and window frames. There is a continuous exploitation of the dwindling forests of the species, including smuggling across the border from Afghanistan.

Bird life is varied. The main valleys and villages inhabited by the Brahminy Myna (Sturnus pagodarum), and the Tree Sparrow (Passer montanus). The main rivers attract the large steely blue-black Himalayan Whistling Thrush (Myophonus caerulesus), and the White Capped Water Redstart (Chaimarrornis leucocephalus). The cliff sides in the valleys provide nesting places for the Blue Rock Thrush (Monticola solitarius) and the Pallid Crag Martin (Hirundo fuligula). Higher up the mountain valleys the magnificent Bearded Vulture (Gypaetus barbatus) with its 8 foot wingspan, flies and glides over the slopes searching for the bones of carrion already picked clean by Himalayan Griffons (Gyps himalayensis), with the rapid staccato calls of the Chukor Partridge (Alectoris chukar) echoing across the valley slopes. The alpine meadows are the nesting place of Guldenstadt's or White-winged Redstart (Phoenicurus erythrogaster) and the Fire-fronted Serin (Serinus pusillus).

Key species amongst the larger mammalian fauna include the secretive Snow Leopard, which wanders over a huge territory in search of prey, in winter sometimes making night-time raids on penned flocks of sheep and goats. The large and handsome Screw Horned Goat or Markhor (Capra falconeri) is prized by local people both as a trophy and for its meat, and has consequently become very rare. However it is preserved in Chitral's only wildlife sanctuary, Chitral Gol, a huge mountain amphitheatre just north west of Chitral Town, where a herd of about 300 animals still survive. In the far northern mountains of the Hindu Kush there are still scattered herds of Himalayan Ibex (Capra ibex). Smaller mammals include the rare and little known Altai Weasel (Mustela altaica), and its favourite food Royle's High Mountain Vole (Alticola roylei).

Reptiles include the Himalayan Pit Viper (Agkistrodon himalayanus) which has to hibernate deep underground for 8 months each year, and the widespread Rock Agama Lizard (Agama causasica) which can often be encountered basking on nearby rock faces bobbing its head rapidly up and down as a territorial display.

The Baroghil Pass, which crosses into the Wakhan corridor, is an excellent area for rare and little known species, and the alpine meadows in the north provide a home for a rich variety of butterflies. Many of these are of Central Asian origin and are otherwise unknown from the rest of the Indian subcontinent. The Cardinal Fritillary (Argynnis pandora) and Marco Polo's Clouded Yellow (Colias marcopolo) are examples. In fact 10 species of Clouded Yellow have been collected from Chitral, as well as 9 species of Snow Apollo's, including the Larger Keeled Apollo (Parnassius tianschanika).

However increasing human population demands on the limited agricultural resources of the region have led to a degradation of both plant and forest cover, and loss of habitat for many species. Domestic herds compete with both Ibex and Markhor for scarce fodder and also introduce the risk of transmissible disease. Deodar and Chilghoza are also affected. Because these species are slow growing, and because most land in Chitral is owned tribally and not by the Government, the Forestry Department has made little attempt either to produce nursery stock or to attempt any large scale re-afforestation.

The valleys of Chitral have been a vital migration route for birds that breed in Central Asia and spend the warmer winter in the Indian subcontinent. These migrations have been traditionally exploited by the Chitralis and huge numbers of migrant duck, waders and even small passerines are killed annually on their passage through Chitral. Goshawks (Accipiter gentilis), Peregrine Falcons (Falco peregrinus) and Saker Falcons (Falco cherrug) also migrate across the Kaghlasht plateau. These species are trapped live for sale to Arab falconers, and for the Punjab Hawk Market in Mianwali. Largely as a result of this the Goshak and the Saker Falcon have almost disappeared from Pakistan.

Faunal limits of land snail distributions in South Asia, from Chitral to Arunachal Pradesh and Sri Lanka.

Fred Naggs

Department of Zoology, Natural History Museum, The Natural History Museum London SW7 5BD

Email: fren@nhm.ac.uk

Studies in the historical biogeography of land snails offer enormous scope for interpreting environmental changes ranging from those brought about by current human activity to events that have taken place through geological time. Explanations for current distributions and patterns of diversity in South Asian land snails can be sought in plate tectonic events, changes in climate and in human impact. The Indian subcontinent can be viewed very roughly as an equilateral triangle for which the angles are the regions geographical limits. These are the Chitral District of Pakistan's Northwest Frontier Province, the eastern part of the state of Arunachal Pradesh in Northeast India and the southern tip of peninsular India and Sri Lanka in the south. A summary view of the snail faunas from each of these areas provides a framework for understanding the broad features of regional land snail distributions.

The snail fauna of Arunachal Pradesh is high in diversity but relatively low in endemism, being an integral part of the so-called Indo Malayan realm with which it shares a wet climate and forested terrain. The origin of this fauna is a complex mixture and Arunachal Pradesh has been described as a faunal gateway between Indian and Malaysian faunas. There is a large proportion of cyclophorid prosobranch snails, about 30%. The physical geography appears to be similar westward across the southern Himalaya but rainfall generally decreases from east to west. From one of the wettest regions on earth in Arunachal, with its closed canopy dipterocarp dominated forest rich in snail diversity, the opposite extreme is reached in Chitral, with an arid environment and only patchy coniferous tree cover, providing habitats hostile to most snail species. A Western Himalaya/Central Asian snail fauna dominates Northern Pakistan. There is relatively low diversity and comparatively few species associated with Indo Malaysian groups. Cyclophorids are restricted to wetter climates and none extend this far west. Moving north from Peshawar over the Lowari Pass into Chitral District the snail fauna changes completely. In Chitral it consists of Palaearctic taxa including genera and even species that are common in Britain. However, these are confined to highly localised habitats such as in the vicinity of springs or in close proximity to streams where night time cooling probably results in the formation of dew. In the totally artificial environments such as are found in hotel gardens in Chitral town there are a few additional synanthropic species including the now cosmopolitan weed species Deroceras laeve, which is likely to have been introduced very recently on garden plants.

A large part of the central region ranging from Baluchistan to Bengal has a greatly impoverished snail fauna, indicative of rapid environmental change, possibly over the past one or two thousand years. Unlike northern Africa, which also has a recent history of increased aridity, there were apparently few available snail taxa capable of exploiting such environments. Some areas of the Western Ghats of peninsular India are less disturbed, endemism is high and diversity generally increases southward. The related snail fauna in Sri Lanka is highly endemic and diverse and is the most distinctly South Asian snail fauna. This description is justified by the diversity of Gondwana relict species but the origin of much of Sri Lanka's snail fauna is obscure and the faunal links with North East India and South East Asia have been difficult to establish. Current molecular studies offer exciting new possibilities for understanding relationships between related groups, when they might have diverged and what environmental events might have been responsible. The current discontinuity between many snail groups in southern peninsular India and Sri Lanka and those in North East India is strongly maintained by environmental factors such as rainfall but there have been times in the past when the faunas must have been closely linked if not continuous. Some ancient snail groups may even owe their present day discontinuity to the formation of the Deccan traps some 65 million years ago. This volcanism has been linked to the K/T boundary extinctions but the survival of Gondwana species, primarily in Sri Lanka, attests to the survival of land snails in close proximity to this massive global event. The earlier break up of Gondwana and events of the magnitude of Deccan trap formation, allow the possibility of establishing hypotheses linking dates to vicariant branching and developing a chronology on molecular trees.

South Asian land snails were studied intensively in the ninteenth century and the resulting concentration of specimen reference collections and related literature resources at the Natural History Museum in London are unique in providing a foundation for future research. Current projects at the Museum using these resources are linked to co-operative field programmes with institutions in the subcontinent. These projects address issues ranging from the transfer of information resources, faunal surveys and taxonomic revision, ecological and life history studies, shell isotope profiles and climate change, and construction of a molecular phylogeny.

Intestinal Helminth Infections in Primary Schoolchildren from the Chitral and Kalash Regions of North West Pakistan

Raymond C. Stoddart

Division of Environmental and Evolutionary Biology, Institute of Biomedical and Life Sciences, University of Glasgow, G12 8QQ

Email: gbza76@udfc.gla.ac.uk

An epidemiological survey was carried out during the 1999 International Hindu Kush Expedition and during the subsequent summer of 2000. The work on the International Hindu Kush Expedition was conducted jointly with Azra Meadows and Peter Meadows. The aims of the two surveys were to investigate the prevalences of intestinal helminth infections in primary schoolchildren. These infections are mostly found in developing countries as a result of poverty, poor nutrition, bad sanitation and a general lack of education and health care. Children who are infected often suffer from reduced appetite, anaemia, nausea, headaches and abdominal pain. In the long term their growth can be retarded when there is malabsorption of food when it is not properly digested. This in turn can lead to a reduction in the ability of children to learn.

Study sites included both boys and girls from Chitral Town, Garam Chashma and the three Kalash valleys of Rumbur, Bumburet and Birir. From faecal samples obtained the following parasite species were observed, Ascaris lumbricoides, Trichuris trichiura, Hymenolopis nana, Taenia saginata and Enterobius vermicularis.

Preliminary analysis shows that although the percentage prevalences of these infections are relatively high, particularly those of Ascaris lumbricoides and Trichuris trichiura. The intensity thresholds indicate light infections (Ascaris <4,999 eggs per gram of faeces, Trichurus <999 eggs per gram of faeces). This study provides a baseline survey for the communities described and a basis for estimating the present status of the children from both rural and urban environments in the Chitral area. It also gives an indication for further research and the need for appropriate intervention within the populations.

It was apparent that much good work was already being done, provided by professionals and local people, and also from foreign participants, however there was a general lack of funds, know how, and in particular an absence of proper coordination whereby problems could be highlighted and prioritised so that the whole community could benefit.

Clearly a proper Control Programme requires setting up with good local input so that useful strategies can be applied. Appropriate intervention in the first instance should look at improving the health status of schoolchildren (5 - 19 years). This should include anthelminthic chemotherapy, micronutrient supplementation and of course health education - hopefully on a routine basis. Funding requires special attention not only in raising awareness, but in proper usage of anthelminthics. Even a small amount of money properly targeted can do much to help local economies and alleviate much suffering. It is believed that the two parasitological surveys conducted in 1999 and 2000 are the first to be conducted in the Chitral region.

The Kalasha: Current Research

Peter Parkes

Department of Anthropology, University of Kent, Canterbury, Kent, CT2 7NS

Email: pscp@ukc.ac.uk

Peter Parkes presented an illustrated synopsis of the annual cycle of agro-pastoral subsistence of the Kalasha ('Kalash Kafirs') of southern Chitral, summarizing his longitudinal research there spanning almost thirty years. Despite some significant recent changes of farming techniques, primarily associated with development programmes introduced over the past two decades, Kalasha retain a distinctive 'mixed mountain farming regime' of goat husbandry and cereal horticulture, underpinned by a ritually sanctioned sexual division of labour. Transhuman pastoralism - whose digital photographic and video documentation was a major topic of ethnographic research undertaken with Saifullah Jan as part of the International Hindu Kush Expedition in autumn 1999 - remains a thriving part of Kalasha subsistence, unlike many other regions of the Hindu Kush and Karakorum, where herding in high mountain pastures has rapidly declined in recent years. The talk summarized an illustrated multimedia document on "Pastoral Transhumance and the Ritual Orchestration of Seasonal Morphology among the Kalasha", examing the religious coordination of 'seasonal socialities' associated with the agro-pastoral subsistence cycle, with comparative reference to Marcel Mauss's seminal essay on The Seasonal Variations of the Eskimo and to contemporary studies of transhumant mountain communities elsewhere in Eurasia. Copies of this paper are available on request, while the full multimedia document will be made available online at the website of the Centre for Social Anthropology and Computing, University of Kent: http://lucy.ukc.ac.uk.

The Kalasha: Indigenous Perspectives

Saifullah Jan, District Councillor, Balanguru, Rumbur Valley, C/O Aiun Post Office, Chitral District, Nwfp, Pakistan

Saifullah Jan is the elected District Councillor of the Kalasha, serving for over a decade as their minority representative and spokesman, as well as working with many outside visitors as a translator and field assistant on Kalasha ethnography. After summarizing his personal experiences in campaigning for Kalasha welfare and minority interests, Saifullah Jan responded to questions from the audience concerning current environmental and development problems of the Kalasha, updating his earlier critique of the adverse effects of several NGO development programmes presented at the 2nd Hindu Kush Cultural Conference [History and development of the Kalasha. In Proceedings of the Second International Hindu Kush Cultural Conference (ed.) E. Bashir and Israr-ud-Din. Karachi: Oxford University Press 1996, pp. 239-46]. Saifullah Jan also alluded to his successful campaign to win forestry rights for the Kalasha or Rumbur valley (as documented in his words in P. Parkes 'Enclaved Knowledge' in R. Ellen, P. Parkes and A. Bicker eds. Indigenous Environmental Knowledge and Its Transformations, Harwood Academic, 2000, Ch. 9, also available online at http://www.mtnforum.org/rs/ol.cfm), pointing to the potential value of indigenous collaboration with outside scientific research teams in developing community-managed programmes of conservation and development in the future.