Seminar: Verbiest’s ‘Kunyu Quantu' (Map of the Whole World)

Published: 12 October 2018

October 2018

Seminar: ‘The Empire’

Verbiest’s ‘Kunyu Quantu' (Map of the Whole World)

Location: Hunterian Museum

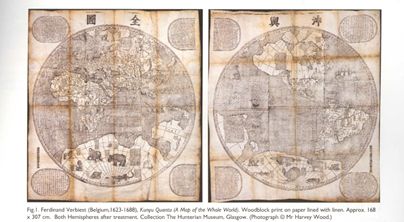

The Chinese Empire in the mid 1600s was vastly growing and mapping became a crucial element particularly in 1644 when the Manchu had overrun China and established the Qing dynasty. The act of mapping aided in establishing power and recognizing the expansion of the Chinese empire more greatly. Jesuit Missionaries were employed by the Chinese court to share their expansive knowledge of Western science, which attests to the presence of the Western world throughout history as seemingly superior. Jesuit Missionary Ferdinand Verbiest printed the Kunyu Quantu in 1674 as part of the ongoing mapping of Chinese territory of which the Kangxi Emperor of the newly established Manchu dynasty, the Qing, commissioned Jesuits to undertake as part of the consolidation of power within China. Reliable maps were required of both the Empire and the world beyond, hence why Verbiest’s map includes information of two hemispheres acknowledging the five continents which were known at that time: Asia, Europe, Africa, America and Magellanica (the uncharted Southernly area of the globe which is shown on the map as a large land mass).

The story of Kunyu Quantu in the Hunterian Museum here in Glasgow begins with Theophilus Siegfried Bayer, a classicist, linguist and a professor at the St.Petersburg Academy of Sciences. Between 1731 and his death in 1738 Bayer began a lengthy correspondence with the Jesuits in Beijing. This correspondence has since become invaluable in the understanding of the provenance of Ferdinand’s Map of the Whole World which now resides in the Hunterian museum. Bayer began his correspondence with the Jesuit Missionaries because he was particularly interested in the structure of the written Chinese language. Although Bayer was largely self-taught as a sinologist and relied extensively upon his correspondence with the Jesuits in Beijing to improve his vocabulary, he is recognized as ‘one of the few Europeans outside the circle of the Jesuits in China, who could read Chinese let alone speak it’.[1]

The year 1669 marks the year when Flemish Jesuit Ferdinand Verbiest came to be appointed Director of the Imperial Observatory. Verbiest, like earlier Jesuits, was familiar with astronomy and cartography. This made Verbiest extremely valuable to Emperor Kangxi’s interest in European science. Although the Chinese always valued precise knowledge of their Empire’s geography, Nick Pearce a scholar of Ancient Chinese Arts, states ‘there were no professional cartographers in China until the late nineteenth century’.[2] Interestingly, Pearce further notes that although Western cartographers ‘concerned themselves with perspective and scale’, Chinese map makers did not feel this was important. It is therefore not unusual for mountains to be drawn in elevation on the map whilst rivers and forestry appear as flat. The maps from the Chinese Empire are therefore often ‘heavily annotated, to compensate for the absence of accurate scale’.[3]The lack of accurate scale is perhaps due to ‘China’s intellectual echelon concerned themselves with astronomy, geography, philosophy, art, literature and religion’ whilst the Western ideal of cartography is very much science based. This makes the map particularly intriguing to investigate as it appears to document not only Columbus’s arrival in the Americas but also mythological animals. It would seem Chinese original process of map-making was primarily an art form as opposed to strictly informative. We know a copy of Verbiest’s map was sent to Bayer in 1732 directly from Beijing by Father Dominique Perrenin due documentation of Bayer’s correspondence with the Jesuit Missionaries. Bayer wrote a letter thanking Perrenin over a year after the map was originally dated to have been sent, this demonstrates the slow and lengthy process of maintaining global connections as correspondence appears to exist between each party at a yearly rate.

When Bayer died in 1738, his collection of books and manuscripts, including the Kunyu Quantu map, were sold by his widow to Heinrich Walter Gerdes. Gerdes was an academic born in Hamburg, where he studied theology and later became a preacher. A mere four years later, Gerdes also passed away in 1742 therefore Bayer’s collection of objects was sold again, this time by Gerdes’ widow. This time round, the collection was purchased by anatomist, obstetrician and collector Dr William Hunter. William Hunter was born in East Kilbride, a town just south of Glasgow and studied Classics alongside Logic, Moral and Natural Philosophy at the University of Glasgow. Although there is no precise date for Hunter’s acquisition of the Bayer collection, it is likely to have been acquired some time between 1765 and 1779. When Hunter died in 1783 he bequeathed his entire collection to the University of Glasgow. The Kunyu Quantu map therefore finally made it to the location of what is now known as the Hunterian Museum.

The map itself places a crucial role in understanding the global lives of objects as it is the only copy of the map with direct provenance to Beijing. Despite the direct link to the Chinese Empire, it has been in the possession of three owners, two of which were German and then finally to the Scottish collector William Hunter. The map is over 333 years old and naturally shows some signs of aging. Kunyu Quantu/Map of the Whole World is made from eight separate scrolls to fit with traditional Chinese presentation, however some time after the map arrived in Europe it was mounted onto canvas, as it is seen today, in the Western manner. Although the linen of the map is undoubtedly not original, it has been in place for around two centuries. The current lining and overall presentation of the Kunyu Quantu has arguably become engrained within the map’s history and social life. The map had been kept in storage for decades before Dr Nick Pearce stressed the significance of the global object in 2007 and encouraged the Kunyu Quantu to be placed on display. A custom display case was made specifically for the map to be publicly displayed and the vast size of the artefact combined with the required quality of the glass for efficient preservation, brought the total cost of the protective glass case to £7,100. It was only in 2007 that the provenance of the Kunyu Quantu was traced directly back to Beijing making the map extremely rare. This demonstrated the way in which new findings within the realm of global history can be discovered even hundreds of years after the object itself was created.

Consider the following:

The Kunyu Quantu was mounted onto canvas relatively quickly after its arrival in Europe and it has stayed that way for over two centuries. How does the Western presentation of history affect our understanding of global relations? If the map had only arrived in Europe today, would it still have been presented through a Western lens?

The cost of preserving the Kunyu Quantu offers some insight into the expense of conservation and display work which takes place surrounding historical objects. Why is it crucial for historical artefacts to be looked after and displayed with such care?

Sources-

Nick Pearce ‘Mapping the World: a Copy of Verbiest’s Kunyu Quantu in Glasgow University’s Collection’ in About Books, Maps, Songs and Steles: The Wording and Teaching of the Christian Faith in China Edited by Dirk Van Overmeire and Pieter Ackerman (Ferdinand Verbiest Institute: Belgium, 2011)

Helen Creasy, Harry Metcalfe and Nick Pearce History and Conservation of Kunyu Quantu (A Map of the Whole World) by Ferdinand Verbiest, 1674

http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/25436/1/id25436.pdf [Accessed 12th June 2018]

[1] Nick Pearce, ‘Mapping the World: a Copy of Verbiest’s Kunyu Quantu in Glasgow University’s Collection’ in About Books, Maps, Songs and Steles: The Wording and Teaching of the Christian Faith in China Edited by Dirk Van Overmeire and Pieter Ackerman (Ferdinand Verbiest Institute: Belgium, 2011) p54

[2] Helen Creasy, Harry Metcalfe and Nick Pearce History and Conservation of Kunyu Quantu (A Map of the Whole World) by Ferdinand Verbiest, 1674 http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/25436/1/id25436.pdf [Accessed 12th June 2018]

First published: 12 October 2018