Current research projects

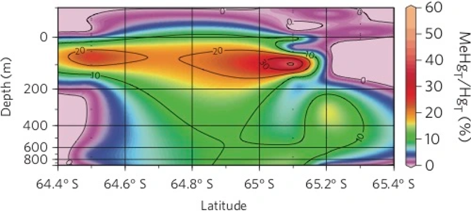

Microbial mercury methylation

Methylmercury in the environment is produced almost entirely by microorganisms, and bioaccumulates as a neurotoxin through terrestrial and marine food webs. We are investigating the microbiology, biochemistry and geochemistry underpinning environmental Hg methylation both in the lab and in the field (ocean, peatlands). We are also interested in the co-evolution of this microbially-mediated process, which originated amongst Earth's earliest lifeforms, with the geochemical evolution of our planet.

The figures below are taken from some of our research group's publications in these topics.

Depth profile of methyl-Hg / Total Hg (%) in Southern Ocean (113-121E longitude); from Sunderland et al. 2009.

KEGG pathways of metagenome-assembled genomes (left) from Saanich Inlet, British Columbia, Canada (right); from Lin et al. 2021.

Maximum likelihood species tree of hgcA+ and merB+ genomes; from Lin et al. 2023.

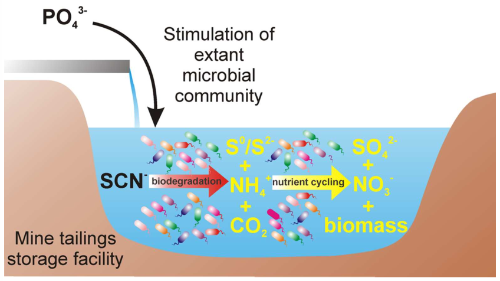

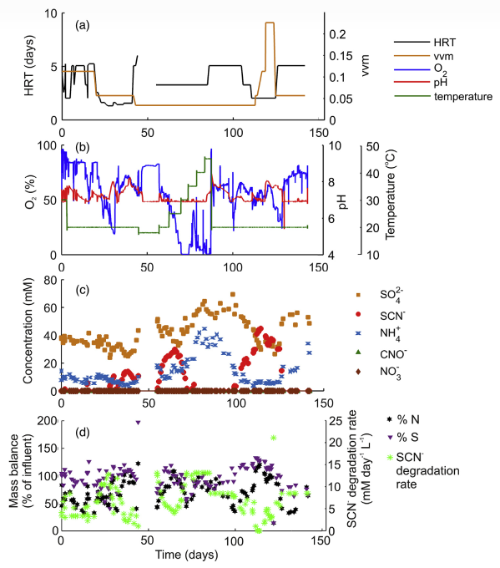

Bioremediation of thiocyanate in mine waste

Some microorganisms have adapted to live in extreme environments, including mining-contaminated toxic wastewaters, and can even metabolize these toxins - transforming them into environmentally benign chemicals. We study the microbes that perform these useful functions, and develop sustainable biotechnology for harnessing their metabolic activity for mine bioremediation, using only atmospheric CO2 as a carbon source.

The figures below are taken from some of our research group's publications in this field.

Conceptual diagram of pipeline decanting thiocyanate-contaminated wastewater from gold ore processing plant, and biostimulation experiment to enhance in situ bioremediation. From Watts et al. 2017.

Experimental data from laboratory bioreactor experiments using native microorganisms from mine waste tailings to degrade thiocyanate; Watts et al. 2019.

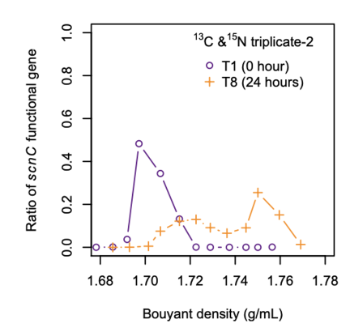

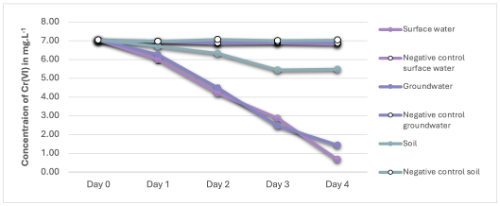

Data from laboratory experiment using 13C and 15N to label functional genes (scnC) of thiocyanate-degrading microbial consortium; Ling et al. 2025

Chromium redox cycling and mobility

Hexavalent chromium [Cr(VI)] is a carcinogenic pollutant from the industrial legacies of steelmaking and chemical manufacturing around the world. Remediation efforts are often challenged by the potential for Cr(VI) to be remobilised via redox reactions with other metals (e.g., manganese). We are interested in these processes at the nanoscale to understand how metals, microbes and organic matter can interact in the environment to control the long-term fate of Cr(VI).

The figures shown below are from previous and ongoing work by research group members.

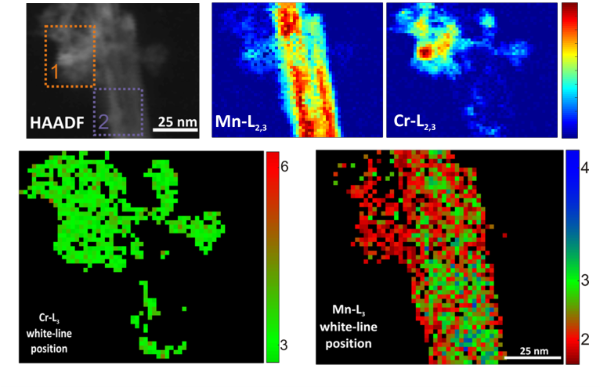

CryoTEM electron energy loss spectroscopy of nanoparticulate MnO2 and Cr(OH)3 after spontaneous redox reactions that change the valence states of both metals; Watts et al. 2015.

Legacy hexavalent chromium pollution in an urban waterway in East Glasgow contaminated by chemical manufacturing. Photo by J. Moreau

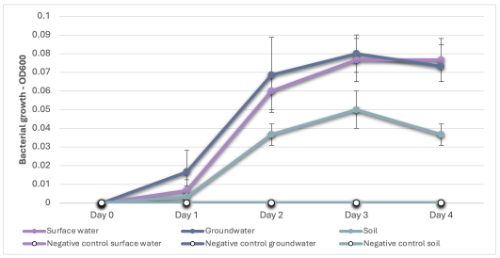

Experimental data showing cell growth (top) and Cr(VI) reduction (bottom) by a laboratory culture of microorganisms enriched from Cr(VI)-contaminated groundwater sampled from nearby the waterway shown above; Davancens and Moreau, unpublished data.

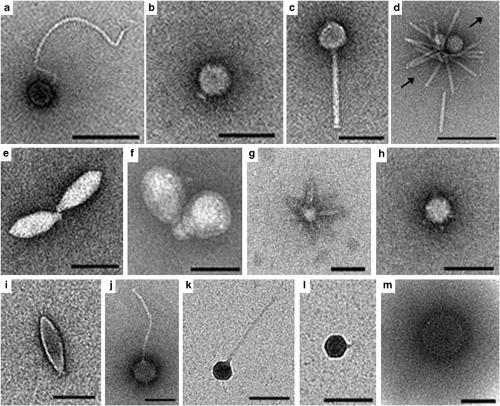

Groundwater virome

In this newly-funded (UKRI Science and Technology Facilities Council) project in the lab, we are investigating the virome of groundwater in basalt aquifers, as a potential lithological/geochemical analog for the subsurface of extraterrestrial rocky planets like Mars. We are also interested in non-basaltic aquifers with specialised chemistries, e.g., the subglacial water table, flooded abandoned coal mines, and the bacterial viruses (bacteriophage) that these formations host. This project aims to understand the effects of bacteriophage lytic cycles on groundwater chemistry through impacting on microbial biogeochemical cycling of major elements and trace metal nutrients.

Viruses in subsurface granites, from Kyle et al. 2008. https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2008.18