Fruit juice – just another sugary drink?

Published: 10 February 2014

Drinking fruit juice is potentially just as bad for you as drinking sugar-sweetened drinks because of its high sugar content, two medical researchers have warned.

Drinking fruit juice is potentially just as bad for you as drinking sugar-sweetened drinks because of its high sugar content, two medical researchers from the University of Glasgow have warned.

Writing in The Lancet Diabetes and Endocrinology journal, Professor Naveed Sattar and Dr Jason Gill – both of the university’s Institute of Cardiovascular and Medical Sciences – call for better labelling of fruit juice containers to make explicit to consumers that they should drink no more than 150ml a day.

The Herald: Fruit juices and smoothies "are as bad for health as fizzy drinks"

They also recommend a change to the UK Government’s current “five-a-day” guidelines, saying these five fruit and vegetable servings should no longer include a portion of fruit juice. Inclusion of fruit juice as a fruit equivalent is “probably counter-productive” because it “fuels the perception that drinking fruit juice is good for health, and thus need not be subject to the limits that many individuals impose on themselves for consumption of less healthy foods”.

Professor Sattar, who is Professor of Metabolic Medicine, said: “Fruit juice has a similar energy density and sugar content to other sugary drinks, for example: 250ml of apple juice typically contains 110 kcal and 26g of sugar; and 250ml of cola typically contains 105kcal and 26.5g of sugar.

“Additionally, by contrast with the evidence for solid fruit intake, for which high consumption is generally associated with reduced or neutral risk of diabetes, current evidence suggests high fruit juice intake is associated with increased risk of diabetes.”

One glass of fruit juice contains substantially more sugar than one piece of fruit; in addition, much of the goodness in fruit – fibre, for example – is not found in fruit juice, or is there in far smaller amounts, explains Professor Sattar.

Although fruit juices contain vitamins and minerals, whereas sugar-sweetened drinks do not, Dr Gill argues that the micronutrient content of fruit juices “might not be sufficient to offset the adverse metabolic consequences of excessive fruit juice consumption”.

In one scientific trial, for example, it was shown that, despite having a high antioxidant content, the consumption of half a litre of grape juice per day for three months actually increased insulin resistance and waist circumference in overweight adults.

“Thus, contrary to the general perception of the public, and of many healthcare professionals, that drinking fruit juice is a positive health behaviour, their consumption might not be substantially different in health terms than drinking other sugary drinks,” said Dr Gill.

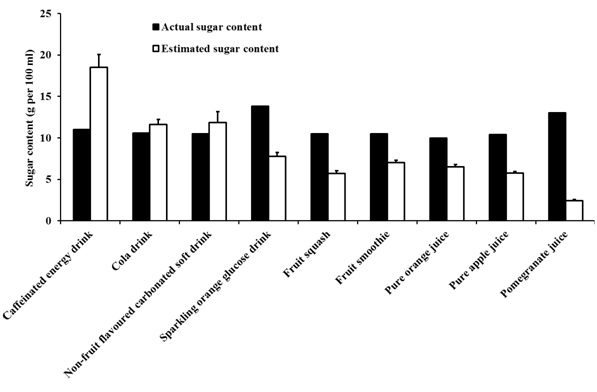

The researchers also tested public awareness of the sugar content of fruit juices, smoothies and sugar-sweetened drinks by carrying out an online poll of over 2000 adults. Participants were shown pictures of full containers of different non-alcoholic beverages and were asked to estimate the number of teaspoons of sugar contained in the portion shown. Although the sugar content of all drinks and smoothies was similar, the sugar content of fruit juices and smoothies was underestimated by 48% on average, whereas the sugar content of carbonated drinks was overestimated by 12%.

“Thus, there seems to be a clear misperception that fruit juices and smoothies are low-sugar alternatives to sugar-sweetened beverages,” said Dr Gill.

There are strong public health reasons for targeting sugar-sweetened drinks, possibly through the imposition of an increase in taxation as a means of reducing consumption, argues Professor Sattar.

While there have been calls in the USA to eliminate all fruit-juice consumption by children, the researchers stop short of recommending similar moves in the UK. They also feel that a fruit juice tax would not be warranted. However, Professor Sattar argues: “In the broader context of public health policy, it is important that debate about sugar-sweetened beverage reduction should include fruit juice.”

The debate around fruit juice comes as medical experts are focusing more closely on the link between high sugar consumption and heart disease risks.

Professor Sattar said: “We have known for years about the dangers of excess saturated fat intake, an observation which led the food industry to replace unhealthy fats with presumed ‘healthier’ sugars in many food products. Helping individuals cut not only their excessive fat intake, but also refined sugar intake, could have major health benefits including lessening obesity and heart attacks. Ultimately, there needs to be a refocus to develop foods which not only limit saturated fat intake but simultaneously limit refined sugar content.”

Find out more

Institute of Cardiovascular and Medical Sciences

Media inquiries: Liz.Buie@glasgow.ac.uk 0141 330 2702

Study inquiries: Professor Naveed Sattar, Naveed.Sattar@glasgow.ac.uk, Institute of Cardiovascular and Medical Sciences.

Dr Jason Gill, Jason.Gill@glasgow.ac.uk, Institute of Cardiovascular and Medical Sciences.

First published: 10 February 2014

<< February