|

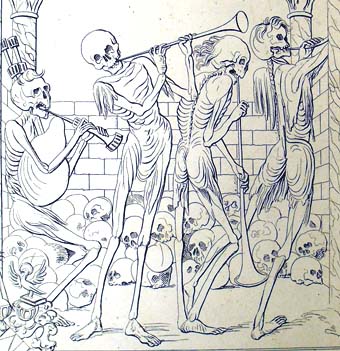

A graphic illustration of

the mural at Lubeck (Gemmell Add f.9) |

The Dance of Death motif has its origins in medieval

society. Although (as scholars such as Francis Douce and Marcia

Collins point out) civilizations had been anthropomorphosising

death for centuries, the Dance is a later concept.

The earliest example of the Dance in graphic art was as an

architectural mural on the walls of the Holy Innocents Church in

Paris in 1424/5. The genre subsequently spread throughout

northern Europe, and similar frescoes appeared in Germany,

Switzerland and even England. Famous Dances of Death were on

view in Basel (after 1440) and Lubeck (after 1463), as well as

on covered bridges at Lucerne (c.1400) and Spruer. Around 1430 a

Dance of Death could also be observed on the cloisters of the

old St. Paul's in London; this was accompanied by French verses

translated into English by John Lydgate.

It is suggested that the Dance's origins may be traced back

to medieval drama. It is known that actors performed the parts

of various members of society being taken by death in a dialogue

between Death and his victims. Janet Barnes, for instance,

claims that the Dance was first recorded as a liturgical drama

to illustrate sermons in Normandy in 1393, predating its

appearance on the church walls in Paris.

|

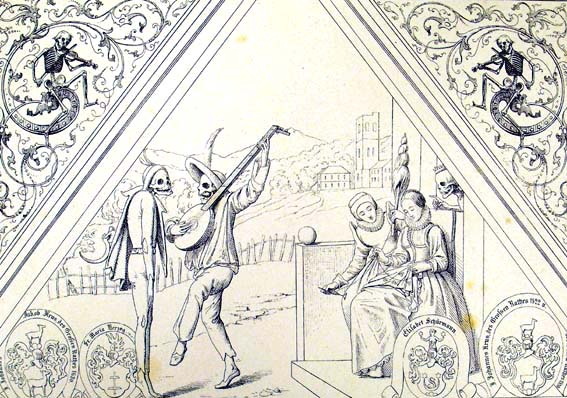

Examples of fresco at

Bern (Gemmell Add f.10) |

|

Reproduction of the Dance of Death fresco at Lucerne (Gemmell

f3)

|

The impetus behind the development of the Dance

remains unclear, yet the historical context is crucial. As

Gundersheimer remarks, the 15th Century was a time of crop

failure, climate change, pestilence, the Black Death and the

Hundred Years' War. The mortality rate was significantly high

and the average man could only expect to live to 50. Public

executions were commonplace and, unlike today, a person could not

expect to reach adulthood without having seen a dead body. |

|

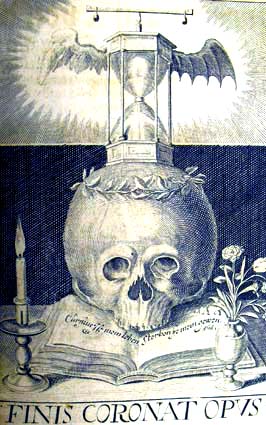

Memento Mori plate

(Gemmell 6)

|

But was the Dance of Death intended as a comfort or a

warning?

On one hand, it offers the consolation that regardless of

one's status in the mortal life, all are equal before death. It

is possible that in bleak times the Dance extended an invitation

to laugh at death and an encouragement to live in the moment.

Yet it also constitutes a stark reminder of impending death,

and serves a didactic function in reminding the viewer to live

and die well. As these two plates show, the Dance could serve as

a momento mori in an age when death could strike at any time.

James Clark concludes that in classical times the memento mori

maxim was an incitement to "eat, drink and be merry;" yet in the

Middle Ages, it became a warning to live a purposeful life.

|

Memento Mori frontispiece plate (Gemmell 14) |

| Yet the interest in the portrayal of death, and

the continued reinvention of the Dance of Death in centuries

that had long-since forgotten the famines and plagues of the

Middle Ages, ultimately demonstrates the universality of man's

preoccupation with death and mortality. The following pages

explore how this medieval theme found its way into print and

continued to thrive through the ages. |

|