“What’s in a name? That which we call a rose by any other name would smell as sweet.”

Published: 6 November 2015

The UK is one of highest consumers of “legal highs” in the world, but what does the term “legal high” mean?

“What’s in a name? That which we call a rose by any other name would smell as sweet.” Romeo and Juliet, Shakespeare

There are a number of new drugs available to individuals both through legal avenues and more underhand means. Around 2008 this wave of new drugs was originally brought to the masses to mimic the effect of the illegal drugs whilst circumventing legislation. The term “legal high” was born. In November 2011, in the UK, Temporary Class Drug Orders were brought into effect to try to start to control these drugs. The idea behind the legislation meant drugs which were thought to be potentially harmful were controlled quickly and within a year could be added to the Misuse of Drugs Act which controls drugs in the UK. Unfortunately this had the undesirable effect of encouraging chemists to change the chemical structure enough to get around the legislation whilst still keeping the “desirable effects”. The term “legal high” is no longer a simple one as some drugs are illegal and not all of them give an effect which could be described as “high”.

Other terms used include “synthetic cannabinoid receptor agonists” or “synthetic cannabinoids”. These usually describe a group of hundreds of different drugs which have been originally designed to mimic the effect of the active ingredient of cannabis (D9-THC). The structures have changed so much that many of them look far removed from D9-THC and there is debate as to whether some even act on the same receptors meaning even this relatively broad term could be considered a misnomer for some drugs. Using terms like “Spice” or “Black Mamba” in the media can also be misleading as these are brand names and NOT the names of the active ingredients. These brands are not specific to an individual drug or chemical. In addition the active ingredient in similar looking packaging can change over time and location, meaning you cannot rely on having the same effect every time you use the same brand. A rose by any other name may NOT smell as sweet.

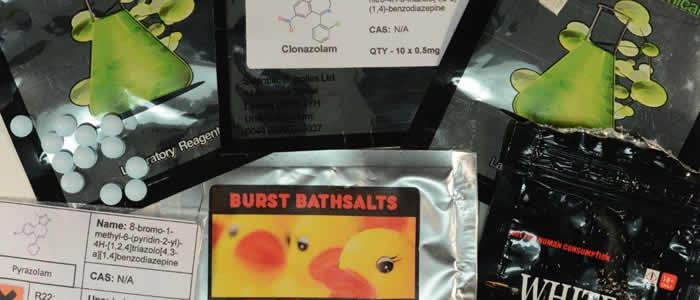

There are many other “legal highs” or “Novel Psychoactive Substances” (NPS) available to the general population, some mimicking diazepam e.g. etizolam, diclazepam, others mimicking stimulants like MDMA e.g. methiopropamine and even ones designed to mimic LSD e.g. 25I-NBOMe. Some of these are illegal and some not. The current UK government are in the process of bringing in a new Psychoactive Substances Bill in April 2016. The new bill will define a “psychoactive substance” and prohibit supply of such substances. We wait in anticipation to see the effects this bill will have to the growing trend of drug use in the UK. Regardless of the legislation we need to make sure that the drug using population understand what they are taking, the legal implications and most importantly the risks to their own mental and physical health. Whilst the classic drugs of abuse like heroin and methadone still top the list of controlled drugs causing most deaths, there is a huge concern regarding the mental health implications of using these newer drugs both acutely and longer term. The University of Glasgow is actively involved in trying to, firstly identify accurately the drugs being used locally and secondly understanding their impact on society as a whole.

Dr Hazel Torrance, Forensic Toxicologist, Forensic Medicine

First published: 6 November 2015