| Please note that these pages are from our old (pre-2010) website; the presentation of these pages may now appear outdated and may not always comply with current accessibility guidelines. |

| Please note that these pages are from our old (pre-2010) website; the presentation of these pages may now appear outdated and may not always comply with current accessibility guidelines. |

Book of the MonthNovember 2009Charles Darwin |

|

|

|

Yet Darwin's caution was arguably rewarded: the

intervening years, from initial discovery to publication, had not only

witnessed the public become increasingly receptive towards new ideas

but the growth of Darwin's reputation and respectability. A theory

that would have been dismissed out of hand by established academics

years before, was now given serious, if guarded, consideration.

The Expression played a significant role in bringing photographic evidence into the scientific world: the photographs in the book constitute one of the earliest examples of attempting to freeze motion for analysis.10 Photography was still a relatively new art form at the time of the Expression's publication. Nevertheless, Darwin believed that it would hold an advantage over other forms of representation since its potential for capturing fleeting expressions with accuracy and detachment would prove more objective. His publisher, John Murray, was less enthusiastic. He warned that it would be necessary to glue photographs into every copy, making their inclusion very labour intensive and costly. The photographer Ernest Edwards (1837-1903) was to provide the solution. Edwards had invented a new photomechanical method of reproducing photographs called heliotype.

|

| Heliotype permitted mass production since it used printing plates

rather than relying on individual prints. It involved coating each

plate with light-sensitive gelatine emulsion, which was then exposed

photographically using an ordinary negative. The emulsion developed

tiny fissures corresponding to the negative - a relief copy - which

was then inked, run through the presses and printed on ordinary paper.11

However Darwin's problems were not at an end: gathering appropriate photographs of human expressions was to prove tricky. He required images of fleeting actions occurring over a fraction of a second, the sort of instantaneous images that contemporary photographers found difficult to produce. Early photographic materials were extremely awkward, unpleasant and time consuming to use and normal exposure times, depending on conditions, ranged from several seconds to two minutes. Not ideal for capturing ephemeral expressions.12 Darwin searched high and low for appropriate images and the ones eventually included were to come from five different photographers. The first suitable images Darwin located already existed in a scientific treatise published a decade earlier by the physiologist Guillame-Benjamin Duchenne (1806-1875). Duchenne, a French doctor, believed that certain neurological problems and muscle disorders were linked to electrical dysfunction within the human body. |

|

|

|

He devised a way of inducing neural action by applying electrical

currents to patients' heads. He learned that it was possible -

particularly with one specific patient - to use the technique to

artificially generate different expressions that could be fixed long

enough for photographs to be taken. With Duchenne's permission, Darwin

used eight of these images in his Expression. Darwin also used images of young children (notoriously difficult to capture due to their inability to stay still) taken by photographers Adolph Kindermann (1823-1892) and George Charles Wallich (1815-1899). Additionally he received numerous photographs of mentally-ill patients from James Crichton-Browne (1840-1938), physician and director of the West Riding Lunatic Asylum. However, only a single engraving from one of Crichton-Browne's images was included in Expression. The numerous woodcuts included in the Expression were cheaper alternatives to the photographs that Darwin would undoubtedly have preferred but could not afford. Interestingly, in some cases, the engravings are not faithful reproductions of the original images. In the engravings from Duchenne's photographs, the electrical apparatus have been removed entirely. |

|

|

|

|

|

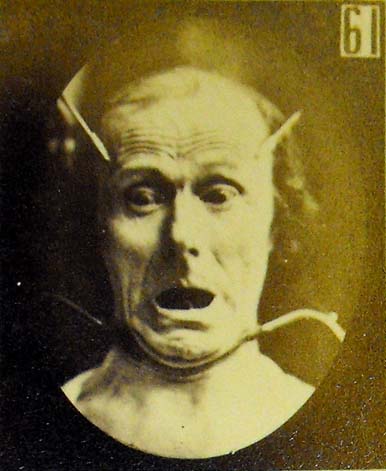

Engraving of a terror stricken

face (left), included in the Expression after a photograph in Duchenne's

Mécanisme (right). Note that the electric |

|

|

The photographer to have the most influence on the

Expression was

Oscar Rejlander (1813-1875), who contributed nineteen of the thirty photographs. Rejlander was a photographic pioneer who strongly believed that

photography had a role in fine art. Having trained first

as a painter, he later turned his hand to the camera, believing

the process could create images every bit as beautiful and meaningful

as any other medium. By the time Darwin and he met,

Swedish born Rejlander had already achieved a degree of fame for his

composite photographs, in which he created elaborate compositions by

combining details from several negatives in a single print.14

In addition to providing one of his famous images of a crying child for inclusion in the Expression, Rejlander and his wife posed for many of the photographs in the work. They can be seen pulling various exaggerated and histrionic gestures, in the belief that such manipulation was necessary to produce convincing illustrations.15 |

|

|

|

|

| With hindsight, it is easy to conclude that the manipulation

evident in both Rejlander's photographs and the engravings taken from Duchenne's

images undermine Darwin's claims to objectivity and

authenticity. While criticisms are justified by modern standards,

photographic historian Phillip Prodger notes that, in the

Expression,

"the distinction between evidence and illustration is blurred because

there is little precedent for the acceptance of photographs as

scientific data. Rules about photographic objectivity did not yet

exist, in part because photographers frequently found it necessary to

manipulate their work to enhance the visual appeal and clarity of

their images."16 The Expression marked the birth of the use of photographs as scientific evidence; obviously, it could not conform to the rules of objectivity and authenticity expected today since such rules were only agreed in debates which acknowledged the Expression's compromises and flaws. Despite the worldwide fame of Darwin and his Origin, relatively few - even in scientific fields - will be overly familiar with his Expression. Concern over the authenticity of the photographs is one possible explanation for why the Expression may have become overlooked for so long. However, a number of other reasons can also be considered. |

|

|

|

One factor contributing to its decline was its tendency towards

"Lamarckian" ideas. Many years before Darwin, the 18th century French

biologist, Jean-Baptiste Lamarck (1744-1829), proposed an alternative - and widely

discredited - theory of evolution. He suggested that through practice

and repetition animals can improve their bodies during life,

adaptations that will be passed on to their children. This theory,

sometimes described as use-inheritance, was quite different from

Darwin's notion of randomly occurring beneficial traits being

preserved through improved chances of survival and breeding success. Initially, Lamarck's

theory was completely disregarded by Darwin; however later, when

revisiting his ideas and modifying his theories to answer critics, he

began to believe that such use-inheritance had a place in the

evolutionary process.17 In the Expression, Darwin describes a form of "Lamarckian" use-inheritance called the principle of serviceable associated habits. It posits that a deliberate action taken when experiencing a specific emotion, if repeated, might become associated through habit, and later be called up by that emotion alone. Such connections, Darwin proposed, might be inherited by succeeding generations. The scientific disproof of use-inheritance appeared just seven years after Darwin's death, and undoubtedly damaged the Expression's scientific standing.18 |

| Another blow to the work was its perceived anthropomorphism. In

the early years of the 20th century, the dominant movement in biology

was towards behaviourism. This approach stated that it was

unscientific to describe what animals did in terms of emotion:

scientists should describe only observable behaviour rather than

attempting to make any inferences about motivation. The Expression therefore, was

soon thought to describe an outmoded and flawed approach.19

Paul Ekman, a psychologist who has written extensively on the Expression, believes that perhaps the most important reason for its fall from favour is the same reason why it has become increasingly relevant once again. The "democratic zeitgeist" of the 20th century, with its "hope that all men could be equal if their environments were equally benevolent", did not sit comfortably with Darwin's biological determinism. The cultural relativism that dominated 20th century social science considered environment as the sole important factor in controlling behaviour. With its claims that expressions are innate, determined by our evolutionary past, Darwin's work did not conform in a world that "reject[ed] inheritance for metaphysical reasons".20 Today most scientists believe that both nature and nurture play a role in all human behaviour. Consequently, the Expression, with its many insights into early human development, has once again been embraced by the scientific community. |

|

|

|

As mentioned above, this year marks the bicentenary of

Charles Darwin's

birth. However it also marks 150 years since, On the

Origin of Species, was first published. Described as, "the most famous book in

science", the Origin has received overwhelming media attention

over the years, particularly during this current celebration.

The University of Glasgow Library is fortunate to boast two copies of

the first edition of Origin; however, in

light of the considerable column inches already devoted to the work

elsewhere, and acknowledging geneticist Steve Jones' comment that, "to

remember [the Origin] alone would be as

foolish as to celebrate Shakespeare just as the author of

Hamlet",21 we chose the path less

travelled by concentrating on the

Expression for this month's discussion.

We are fortunate to hold three copies of the Expression: the featured copy comes from our Dougan Collection. Containing a wealth of early photographic material, the collection was purchased in 1953 from Robert O. Dougan, then Deputy Librarian of Trinity College, Dublin, and subsequently Librarian of the Huntington Library, California. |

Darwin, C. (1839). Journal of researches into the geology and natural history of the various countries visited by H.M.S. Beagle...from 1832 to 1836. London: Henry Colborn. Library Level 12 Sp Coll BG54-f.16.

Darwin, C. (1859). On the origin of species by means of natural selection. London: Murray. Library Level 12 Sp Coll 650-651 (2 copies)

Darwin, C. (1871). The descent of man, and selection in relation to sex. London: Murray. Library Level 12 Sp Coll 2991-2992.

Darwin, C. (1872). The expression of the emotions in man and animals. London: Murray. Library Level 12 Sp Coll 652 and Library Research Annexe Store Stone 763. (2 additional copies)

Darwin, C. (1948). The expression of the emotions in man and animals. Revised and abridged by C. M. Beadnell. London: Watts & Co. Library Level 12 Sp Coll Laing 1401.

Duchenne, G. B. (1862). Mécanisme de la physionomie humaine ou Analyse électro-physiologique de l'expression des passions. Paris: Renouard. Library Level 12. Sp Coll Dougan Add. 85-86.

The complete works of Charles Darwin, including his correspondence, is available online at the Darwin Online website.

Browne, J. (2002). The power of place. Volume II of a biography. London: Jonathan Cape. Level 5 Man Lib Biology A31.D2 2002-B

Darwin Online (2009). The expression of the emotions. [online] (updated 6 October 2009) Available at: http://darwin-online.org.uk/EditorialIntroductions/Freeman_TheExpressionoftheEmotions.html

Desmond, A. & Moore, J. (1991). Darwin. London: Michael Joseph. Level 5 Man Lib Biology A31.D2 1991-D

Desmond, A., Moore, J. & Browne, J. (2004). Darwin, Charles Robert (1809-1882), naturalist, geologist, and originator of the theory of natural selection Oxford Dictionary of National Biography [online] Oxford: OUP. Available online from our database pages.

Ekman, P. (ed.) (2009). The expression of the emotions in man and animals. (by Charles Darwin) Anniversary edition. London: Harper.

Jones, S. (2009). Darwin's island: the Galapagos in the garden of England. London: Little, Brown. Level 5 Man Lib Biology A31.D2 2009-J

Prodger, (2009) Photography and The Expression of the Emotions. Appendix in Ekman's (ed.) The expression of the emotions in man and animals. (by Charles Darwin) Anniversary edition. London: Harper.

Richards, R. J. (1987). Darwin and the emergence of evolutionary theories of mind and behavior. Chicago, London: University of Chicago Press. Level 5 Man Lib Biology R30 1987-R2

References cited

1. Desmond, Moore and Browne.

2. Browne, p. 332.

3. Jones, p. 76.

4. Ekman, p. xxi.

5. Browne, p. 369.

6. Jones, p. 4.

7. Browne, p. 368.

8. Desmond, Moore and Browne.

9. ibid.

10. Prodger, p. 401.

11. ibid.

12. Prodger, p. 403.

13. Ekman, p. 302.

14. Prodger, p. 408.

15. Prodger, p.409; Browne, p. 367.

16. Prodger, p. 409.

17. Ekman, p. xxxii.

18. Richards, p. 232.

19. Ekman, p. xxx.

20. Ekman, p. xxiv

21. Jones, p. 3.

Return to main Special Collections

Exhibition Page

Go to previous

Books of the Month

Robert MacLean, November 2009